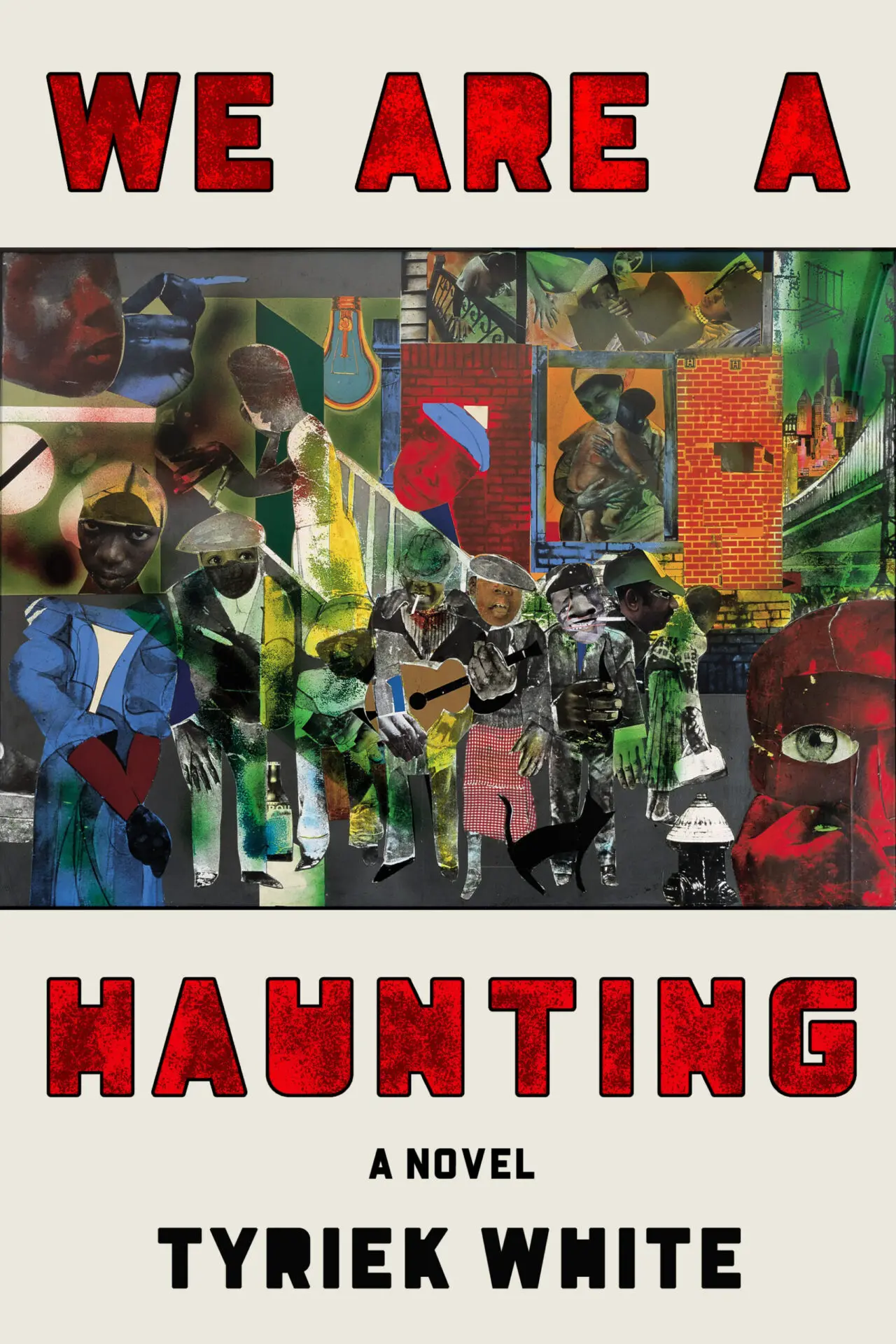

Tyriek White’s debut novel, We Are a Haunting, is a close study of the relationship between a mother and son and how unanswered questions, time, and dead spirits shape their understanding of each other. White’s work is brave, raw, and tugs at the essence of New York City. As we time travel and bear witness between the living and dead, the past and present, you can’t help but fall in love with this cast of characters, worry about them, and ultimately wish them well.

In an interview with TC. Mann, Program Assistant for Literary Writing Programs, White opens up about his artistry and the people who inspired him.

1. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

There’s this moment where Key, one of the main characters in my debut novel, We Are a Haunting, doesn’t give us the ending to a story she’s been telling her son Colly (and the reader). She struggles with whether some stories, while they are hers to tell, don’t solely belong to her and chooses to leave it open for interpretation. She also questions the necessity of telling us this key fact, what that does to the production of meaning. It’s a very meta conversation, one I struggle with when writing about people I know and typically care about. Especially writing a novel about settings and groups of people who are traditionally flattened by mainstream media and historical representations. I wanted to be intentional. It forced me to pay attention more, to interrogate why I’m telling this story, and honestly, if it’s anyone’s business.

2. How does time help shape this story?

This book pushes back against time as a linear experience and shows the past crashing into the present, sometimes in painful ways. Colly’s journey is different from his mother’s (they are at different points in their lives) but they often speak back to each other. Choices made before either are born affect their way forward. Even spatially, the community this family lives in — the broken Waste Treatment Plant, electric substations from the mid-1900s, the industrial park, the streets named after slave-owners, crime rates that mirror decades before, the new buildings that have sprung from thirsty realtor groups — all show a community that often feels outside of time.

“Especially writing a novel about settings and groups of people who are traditionally flattened by mainstream media and historical representations. I wanted to be intentional. It forced me to pay attention more, to interrogate why I’m telling this story, and honestly, if it’s anyone’s business.”

3. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

I’m excited by a lot of poets; Nadia Alexis, Nabila Lovelace, Jonah Webster-Dixon, Sadia Hassan. There is something about writers from the south, or navigating the south, that speaks to resilience, restoration, and reclamation in this country.

4. Why did you choose to focus on Key’s relationship with Colly, instead of her relationship with Toya? How has this decision impacted the story?

I’ve always wanted to write about a mother and son because of how much it played a part in my life and the lives of my friends. There’s so much criticism as to whether mothers can even raise sons, from well-meaning people to blind evangelicals of the Moynihan report, still pushing decades-old narratives.

I think a bit of Toya’s relationship with her mom is reflected in Key’s relationship with her own mother, Audrey. I always imagined Toya as having a completely different way of seeing, or processing than Colly. It would be a different story.

5. What was your creative process when it came to exploring Key’s voice?

Key’s voice is really an amalgamation of my aunties and cousins, the friends I’ve had growing up, etc. I wanted Key to be relatable, despite her gift of seeing. When we meet her, she isn’t happy with her job, she’s boosting designer clothes, and is searching for something more. She goes through a change where she must accept what is happening to her and she embraces it. She grows into who she is supposed to be. I wanted her to be in lineage with women depicted in great literature, in Sula or Brown Girl, Brownstones, or Mama Day.

“It is why there is so much investment, politically and even historically, in the erasure of books by certain communities or voices. Writing about alternate paths forward can create new perspectives and ways we resist.”

6. New York City becomes a character unto itself. Can you tell us how NYC helped in the telling of this family?

New York can be a different place for different people. Half the fun was asking my dad about growing up when he did, or researching the lives of other people living in the city during a specific era. What kind of clothes or name brands did folk wear, what music did they listen to, what were the popular clubs or hangouts?

7. We are all familiar with the mantra, “No child left behind.” What was your intention in addressing these young people’s journey of survival?

It’s such a particular time period for kids. I grew up during that era, the No Child Left Behind policies of George Bush in the early-2000s. I know the failing schools were mostly in Black and brown communities, and were shut down or carved up into three or four separate schools in one building. I remember test scores were an obsession. I don’t really remember if the whole thing worked or not. Probably not.

8. How can writers affect resistance movements?

I’m never into the idea that art can ever do the real work of people involved in resistance movements, or organizing in their communities. What I do think writers can do is create art that begins to reimagine the world we live in and possible futures. It is why there is so much investment, politically and even historically, in the erasure of books by certain communities or voices. Writing about alternate paths forward can create new perspectives and ways we resist.

“I think a writer’s positionality is essential to what stories they choose to tell, no matter how hard artists wish to remain objective. I’m a black boy who grew up working class, in public housing, in one of the worst neighborhoods in Brooklyn. This is how myself and my work will be received regardless. My concerns are very particular.”

9. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

Free expression has been challenged consistently by legislature, whether banning critical race theory or reactionary politics to queer and trans identities. It’s odd having your history pushed out of classrooms, as if it ever fully existed there in the first place. The biggest threat to me, however, is access. Folk on the fringes of society; poor and working people of various identities — do not have access to the spaces or rooms that privilege certain voices.

10. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity”?

I think a writer’s positionality is essential to what stories they choose to tell, no matter how hard artists wish to remain objective. I’m a black boy who grew up working class, in public housing, in one of the worst neighborhoods in Brooklyn. This is how myself and my work will be received regardless. My concerns are very particular. I do believe people from disenfranchised communities understand on an intimate/personal level the inner workings of empire. I think if you’re writing a story outside yourself or challenging genre (like the surreal or even Sci-fi), there should be some truth you are pursuing or questioning, whether an emotional truth, or society, etc.

Tyriek Rashawn White is a writer, musician, and educator from Brooklyn, NY. He is currently the media director of Lampblack Literary Foundation, which seeks to provide mutual aid and various resources to Black writers across the diaspora. He has received fellowships from Callaloo Writing Workshop, New York State Writers Institute, and Key West Writers’ Workshop, among other honors. He holds an MFA in fiction from the University of Mississippi.