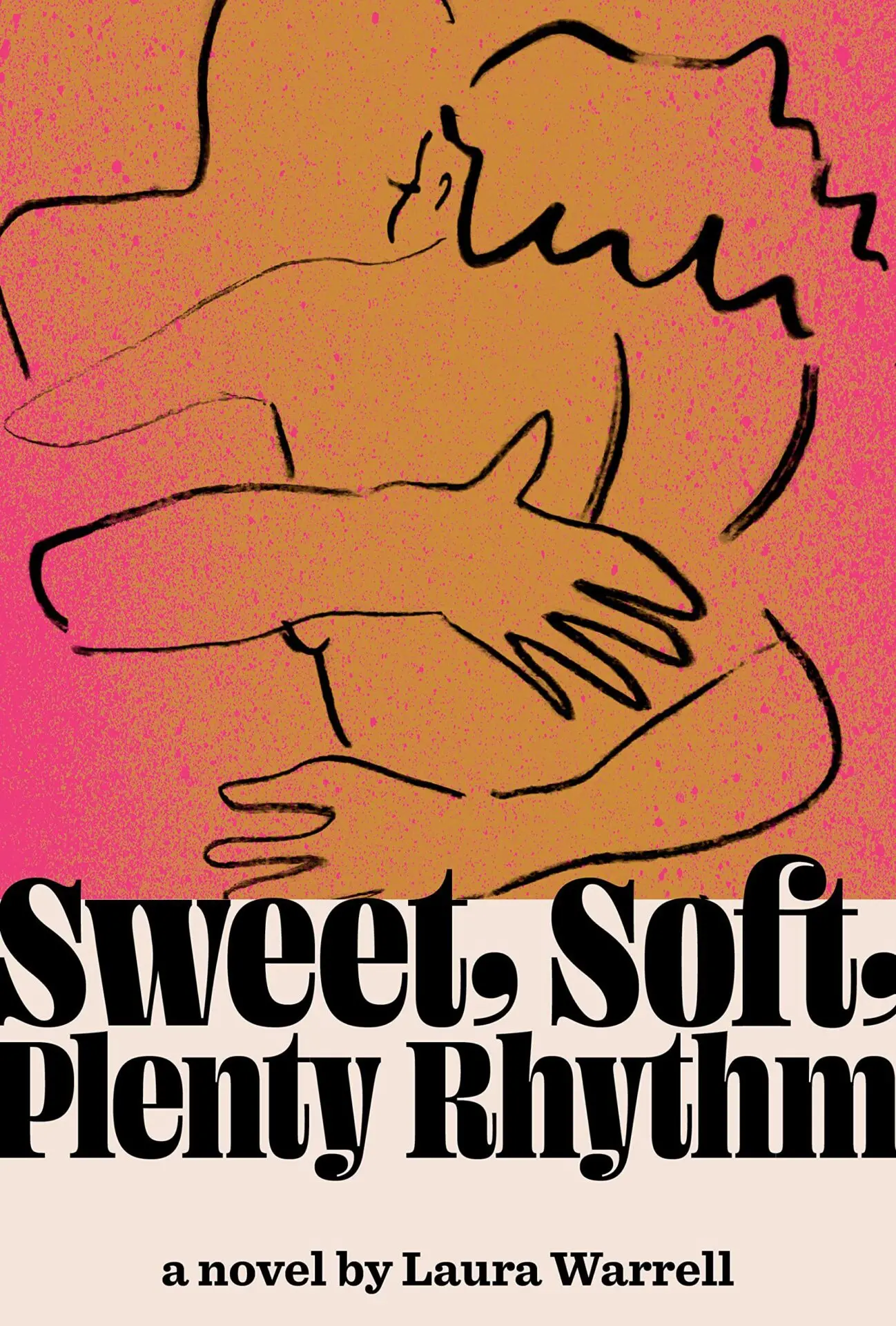

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America’s Literary Programs and Emerging Voices Assistant TC. Mann speaks with Laura Warrell, author of Sweet, Soft, Plenty Rhythm (Penguin Random House, 2022). Amazon, Bookshop.

1. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

Ten people can experience the same situation in the same room, and come away with ten different “truths” of what happened. To me, this is one of the most tantalizing and bewildering facets of the human experience, and one I like to explore in my fiction. In Sweet, Soft, Plenty Rhythm, each woman experiences Circus, and love itself, differently. For instance, one woman sees him as a lion, another as a bear. One woman sees love as a burden, another as the sole reason for living. By considering all these different versions of the same realities, we understand the nature of truth as relative.

But I hope my work takes another step in the direction of truth in that it, hopefully, shines a light on the truths we see as settled in our culture, but only because they’ve been decided by those with more influence. For instance, power dynamics in cis-hetero relationships are often painfully imbalanced, which can have dire consequences for the less empowered person. One of the ideas underlying those dynamics that Sweet, Soft, explores is the notion that men can’t help but play the field and that women should make adjustments to their expectations if they want to keep their romantic relationships afloat. And while I’m not making a statement on monogamy here, I do think it’s reasonable to expect respect and basic human kindness from the person with whom you share a bed. So maybe it’s true that men like Circus need variety in their sex lives, but it’s also true that some of the women those men want to become involved with seek fidelity and, therefore, shouldn’t be expected to excuse unkind behavior.

2. Circus is complex; as the author, what strategies did you use to get close to his character?

No character came easier to me than Circus. I could hear and see him. I knew what he watched on television, how he walked and chewed his food. I saw the women in his life the way he saw them – what it was about their beauty or personalities that turned him on, in part, because like Circus, I see what’s seductive in any woman. But I also think I just get him; I understand the need to be free to pursue romantic connections and design a life that feeds and sustains your creativity. Maybe I’m a little in love with Circus and what you love, you try to understand.

To get close enough to present him authentically, I had to invent a history that explained both his womanizing and his immense appeal to his lovers. I also wanted readers to recognize his complexity even if they disliked him. So, what might have happened to make him detach enough to feel comfortable taking advantage of others, but not so much that he can’t still entice them? I don’t love narratives that try to pin a character’s faults on a single cause, but you’ll see hints at Circus’s early family life and boyhood. Some of this came from research I did around creativity and emotional detachment; it also came from learning about some of the jazz greats. Many of them had challenging upbringings, to say the least, so it makes sense that they’d turn inward. I think, as authors, we have to be able to understand and justify our characters’ actions, and have compassion for where those actions come from. Otherwise, we might create flat characters.

“I think, as authors, we have to be able to understand and justify our characters’ actions, and have compassion for where those actions come from. Otherwise, we might create flat characters.”

3. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

I’m a schedule and list maker so every week or so, I make a list of tasks and always make sure to include at least two hours of writing every day. Admittedly, I don’t always stick to it. As an adjunct professor, it’s hard to balance the workload; one day you’ve got a hundred papers to grade and three classes to teach, the next, you’re free. But I try to write five days a week, if not more.

I find the momentum builds the deeper I get into a project. Once I know the characters, once the plot’s cooking, I have to get back in front of the computer. The book’s constantly writing itself in my head so once I’m sitting down, I experience a kind of outpouring that’s incredibly satisfying.

Of course, I get stuck sometimes and when I do, I turn to other people’s art. Maybe I’ll grab a book of poetry off the shelves or listen to music that matches the vibe of the characters or story.

4. Pia, besides Koko, is the only woman whose story reoccurs. Why is this, and what does her perspective of Circus add to the plot?

One could argue that Pia is the woman who got closest to Circus. He was moved enough by her to pursue a more serious relationship and ultimately marry her when she became pregnant with Koko rather than running away, which we know he’s capable of doing. She lived with him for years and even though he wasn’t around much – and constantly betrayed her – she saw a side of him that’s capable of domesticity and consistency of a sort. Pia, like Koko, brought out a tenderness in him and I imagine their shared life was fun and intoxicating for Pia, even though it was likely stifling for Circus. The other women in the story demonstrate what’s compelling about Circus in the initial stages of seduction, but Pia’s presence demonstrates how satisfying it is when a dynamic man like Circus decides to fully engage for a while, and how desperately lonely it is when he disengages.

To me, the plot follows two threads: in the first, we want to see whether Circus will grow to meet his responsibilities; in the second, we want to see if the women will find the courage to liberate themselves or shift the dynamics of their relationships with him. For Pia, who has built her life around Circus, the stakes are high.

5.What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know about?

On the day I write this, I learned of the death of the great Spanish writer Javier Marias who was one of my most beloved writers. What he did was magic and I don’t quite know how to explain it. In my favorite book by him, Tomorrow in the Battle Think on Me, a man goes to a woman’s apartment to have an affair with her and she dies in his arms. The first forty or so pages are a deep and prolonged contemplation of this moment, what it means for the character and what it reflects about existence. Marias’s work is philosophical, poetic, beautifully plotted yet riddled with delicious digressions and lengthy meditations on the human condition. I don’t know how he did what he did, but I regret that we won’t get to see more of his work. I highly recommend readers seek him out.

“I worry about the consequences for writers, educators, and thinkers, and for citizens who try to assert themselves in an increasingly hostile public space. What gives me hope is seeing the work done on all levels of society to push back.”

6. Out of Circus’s women, who was your favorite to write and get to know?

Koko and Maggie are the characters I love most – Maggie, because she’s so free-spirited and full of life, and Koko, because she’s deeply passionate and wise beyond her years. However, Maggie was most challenging to write, in part because she’s so darn happy and well-adjusted, and I guess sadly (and amusingly), I can’t entirely relate. More importantly, I think character rests on the internal conflict that drives a character to seek and act, but Maggie is just not a terribly conflicted person. She knows who she is and what she wants. She’s overcome her challenges, which I don’t necessarily think were many, and lives authentically. So, I had to bring a conflicted situation into her life that would challenge her to reconsider a pretty perfect life. It was fun to get to know her and spend time with her; I was as charmed by her as Circus was.

Still, Koko might have my heart and I’m not sure whether my abiding affection toward her is because she’s a version of my younger self or a kind of daughter. What I do know is that I felt quite protective of her, which is unfortunate, since my job as her author was to make things as hard as possible for her.

7. What artists or songs did you listen to when preparing to write about Jazz?

What a thrill to take a deep dive into the history of jazz, which is exactly what I did while writing this book. For one, jazz is Circus’s life so I needed to understand it as more than a fan. I went all the way back, starting with Jelly Roll Morton and Sidney Bechet (who I adore) then moving forward to get a sense of how the music evolved and how each artist added his or her variation on the form. Obviously, most of the artists and records I knew, but I wanted to gain historical perspective. I also listened to the artists I think Circus admired – Lee Morgan and Dizzy Gillespie, especially. Then there are contemporary artists I love like Kamasi Washington, Robert Glasper, and Esperanza Spalding.

In order to get into the heads and hearts of the female characters, I listened to songs I either thought they liked (Peach loves rockers like The Black Keys, Koko likes Rihanna and Lorde) or that “sounded” like them. For instance, Odessa wasn’t a character whose tastes I identified clearly, but she came to me as a smooth, sexy, groovy woman so I listened to a lot of “chillout” and acid jazz playlists when I wrote from her perspective.

8. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

The threats to free expression, like all of the threats to our democracy at the moment, come from those who understand the power of knowledge, of sharing ideas, of mutual understanding and respect between members of a society, and who capitalize on the fears some people have toward the unfamiliar so that they can stay in power and further aims that have nothing to do with enriching the culture or bettering lives.

While, so far, I’ve not had serious challenges to my right to free expression, I’m terrified for the future. The successful efforts to ban books and subvert academic curricula are only some of the signs that don’t bode well. I worry about our schools, our media, and every space in our culture where ideas are exchanged and truth is sought. I worry about the consequences for writers, educators, and thinkers, and for citizens who try to assert themselves in an increasingly hostile public space. What gives me hope is seeing the work done on all levels of society to push back.

“It can be excruciating to live with uncertainty and, by creating stories, we can make sense of the nonsensical. We can decide how to act. We can move forward.”

9. What advice do you have for young writers?

If there’s anything to learn from my experience with writing and publishing, it’s the importance of persevering. It took me twenty-five years, five books, and countless agent queries before I got the agent who landed me a book deal. I assume most people won’t have such a torturous journey and I know it’s easy to say “don’t give up,” but what I hope to convey is the importance of loving the work enough to endure and hone your craft.

Additionally, I’d also recommend separating writing from publishing in your mind. When you accept that publishing is a business (among other things, of course), it’s easier to not allow the whims of the market to dictate how you feel about yourself as an artist. For a good portion of aspiring writers, the journey will be difficult, and it’s faith in the work that keeps you going.

10. Why do you think people need stories?

Alice Walker, Joan Didion, and so many other writers have told us they write to understand what they think or feel, and I believe readers come to stories for the same reasons. We all create narratives out of the circumstances of our lives because life is chaotic and deeply confusing, and unfortunately, there is rarely linearity or clear meaning behind what happens to us. Even after something as simple as not getting a phone call from a crush, we concoct elaborate tales about the connection we had with the person, their psychology and background, the conclusion we’ve drawn about what they’re doing instead of phoning us, all in an effort to fill in the mystery, which we’ll never really solve. Why do we do it? Because it can be excruciating to live with uncertainty and, by creating stories, we can make sense of the nonsensical. We can decide how to act. We can move forward.

The magic happens when we share stories – whether the stories we tell our friends, the legends passed down through generations, or the yarns spun in novels – that connect us to others and fosters mutual understanding.

Laura Warrell is a contributor to the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and the Tin House Summer Workshop, and is a graduate of the creative writing program at Vermont College of Fine Arts. Her work has appeared in HuffPost, The Rumpus, and the Los Angeles Review of Books, among other publications. She has taught creative writing and literature at the Berklee College of Music in Boston and through the Emerging Voices Fellowship at PEN America in Los Angeles, where she lives.