The PEN Ten: An Interview with Kimberly Nguyen

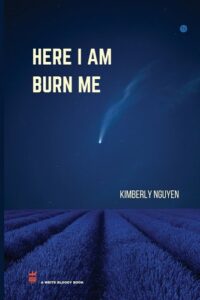

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America’s Los Angeles Program Director Jenn Dees speaks with Kimberly Nguyen, author of Here I Am Burn Me (Write Bloody Publishing, 2022). Nguyen laments the sometimes lonely but often self-affirming journey of poetry in the backdrop of her Vietnamese upbringing. Amazon, Bookshop

PEN America 2021 Emerging Voices winner Kimberly Nguyen by Beowulf Sheehan

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

It was the poem “There Will Come Soft Rains” by Sara Teasdale within the short story also titled “There Will Come Soft Rains” by Ray Bradbury. It was one of the first things I read in high school, my first “big-kid” poem. It was also the first time I read a poem where I immediately felt connected to it, where I didn’t have the language to describe how it made me feel. I just knew that somehow I had been changed, that this poem had unlocked something in me I didn’t know existed.

2. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

I had a writing professor who began nearly every class with the rhetorical question, “What does it mean to be an honest writer?” This question forced me to think about my writing and its relationship to truth. It’s a question that I return to again and again in my writing practice. My answer has changed as I have grown and changed as both a person and a writer, but I think the foundation of my answer remains the same. I believe that fiction is a mask, and the truth lurks somewhere underneath. Part of the work I do before I even start writing any words on the page is self-evaluation. My best poems question and chip away at the mask and expose the raw truth, even when that truth is ugly.

“I believe that fiction is a mask, and the truth lurks somewhere underneath.”

3. What is your favorite bookstore, or library?

The Milton R. Abrahams Branch of the Omaha Public Library. It’s nothing grand or remarkable. You could drive by it and miss it. But as a kid without money, it was my ticket to every possible world. I read voraciously. I owe my entire early childhood development and writing career to this public library branch.

4. Your poem “Writing is Always A Political Act” gestures to both the power and vulnerability of putting oneself into language. Why do you write?

I write because I yearn for connection. Writing is my attempt to show everyone how I experience the world and what my internal world looks like, all with the desire to be seen and understood and loved. I was once told that the Judeo-Christian god created the world because he was lonely; in the void before the world there was no one for him to love. So he speaks into that void in an attempt to reach someone, and the world manifests itself.

5. What is one critique of your work that you have really learned from?

Once, I brought a draft of what I thought was some of my best work to workshop, and my mentor told me, “You’re smarter than this.” It was damaging to my ego. I had been proud of the draft at the time that I finished it. It’s easy to hear other things when we receive critique, like “you’re not good enough” or “you’re a failure.” My mentor and I spoke afterwards, and I came to realize that the critique came from a place of love and faith, that they only said it because they fully believed I had a higher potential to reach and that I should do the reaching.

“I write because I yearn for connection. Writing is my attempt to show everyone how I experience the world and what my internal world looks like, all with the desire to be seen and understood and loved.“

6. There is a potent line in the poem “Relapse Again:”

i am teaching myself the art of ignorance. just because something is

there does not mean i have to find it

Can you share a bit about this art of ignorance and its relationship to your writing?

I was once told that a poem is not finished until there is nothing left to excavate—that a good poem keeps asking “why?” until there are no more why’s left to answer. One thing that I have discovered from this practice of excavating is that some things are not mine to know, that knowing them may not serve me and might harm me instead. I’ve also discovered that sometimes, I’m not actually excavating anything new. I am reburying the same answer and digging it up again hoping that it changed. It never does. I am learning both as a person and a poet to let it be, to accept the answers as they come, to accept that some answers won’t come.

7. What’s a piece of art (literary or not) that moves you and mobilizes your work?

I am particularly compelled by film. I like film that isn’t afraid to take risks, that expands our idea of perspective. Recently, I watched Mắt Biếc, a Vietnamese film available on Netflix, and I was impressed by the use of location to represent innocence and loss of innocence. The film also depicts this really poetic idea of love. As someone who feels love, heartbreak, and grief deeply, I felt a personal connection to this film.

8. What advice do you have for young poets??

I have two pieces of advice. One, find a day job you can live with, which is to say find a job that pays you well enough that you’re not spending brain energy stressing about rent or your next meal, but don’t pick a job that you’re going to spend brain energy absolutely detesting, either. Secondly, make sure this is really want you want to do. Poetry is difficult work, and no one will validate it. You will have to sit around the Thanksgiving table and answer really uncomfortable questions about how much money you make from poetry, while the rest of the table laughs. I had a boyfriend break up with me because I’m “poor.” Make sure poetry is truly your calling because you will sacrifice a lot for it.

“Being a chị hai in a Vietnamese family is being the eldest daughter, and by simply being the eldest (and a girl) I was expected to take responsibility for the family and its needs. I was always asked to sacrifice for the sake of my family. My decision to become a writer was, for my position in my family, a selfish choice.”

9. A recurring motif in your new collection is meditation on being chị hai, an elder sister, incurred as if a song, in the form of verse, refrain, encore. Can you share a bit about this way of being, what it means to you, and/or how it has impacted your relationship to your work?

It was always repeated to me during my childhood, and so it felt fitting for it to haunt my collection. Being a chị hai in a Vietnamese family is being the eldest daughter, and by simply being the eldest (and a girl) I was expected to take responsibility for the family and its needs. I was always asked to sacrifice for the sake of my family. My decision to become a writer was, for my position in my family, a selfish choice. It was impressed on me that I should choose a path with guaranteed high earnings so that I could turn around and help the family. It has created a tension between me and my work because ultimately, my work represents myself and me choosing the work is me choosing myself. But above me is always an overwhelming sense of duty. I often feel caught between the two.

10. As a poet in the age of social media, I’m curious to know more about your feelings about building literary community online. How has Twitter, specifically, shaped you as a writer?

I have a love-hate relationship with the Internet, particularly social media. It’s been a great resource, connecting me to writers I wouldn’t have otherwise met organically, and I’ve learned about submission calls and free workshops through it. I feel validated when I post an achievement and it gets lots of likes or comments. However, it gives me a platform to compare my journey to others, something I know I shouldn’t do, but I can’t help it. And that comparison makes me feel so much pressure to constantly be creating, to never allow myself rest, to be impatient with my work. There is a balance to be struck that I don’t think I have yet mastered. I think the question I should be asking is not how Twitter has shaped me but how I can shape Twitter and other forms of social media. In the age of constant consumption, how can I encourage myself and others to take a break and to slow down, to give the mind rest?

Kimberly Nguyen is a Vietnamese-American diaspora poet originally from Omaha, Nebraska but now living in New York City. Her work can be found in diaCRITICS, Hobart, Muzzle Magazine, The Minnesota Review, and others. She was a recipient of a Beatrice Daw Brown Prize, and she was a finalist for Frontier Poetry’s 2021 OPEN and New Poets Awards and Palette Poetry’s 2021 Previously Published Poem Prize. She was a 2021 Emerging Voices Fellow at PEN America and is currently a 2022-2023 Poetry Coalition Fellow.