The PEN Ten: An Interview with Kristín Ómarsdóttir

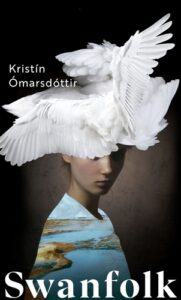

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America’s Literary Awards Assistant Lili Stern speaks with Kristín Ómarsdóttir, author of Swanfolk (HarperVia, 2022). Ómarsdóttir’s Swanfolk tells the mystical story of a young spy who discovers a fused species of swan women. Amazon, Bookshop.

1. What was your inspiration for this novel? How did you come up with the idea of a creature that is half human half swan?

A guy asked me to write a story for kids. I drew and wrote a story about a Blueland where Swanfolk lived. I left it behind; I lack skills for writing for children. Shortly after, one morning writing on my computer this spy Elisabet appears. She finds these creatures in a hollow near the lake where she usually goes hiking after work. I drew the creatures almost simultaneously as I wrote about them. I was inspired by our contemporary times and the growing possibility of this world’s end. The story is told from some distance, from the future. It tells of events which happened in a world that no longer exists.

2. Why did you choose to use myth to represent the deteriorating psychological state of your protagonist, Elisabet?

As soon as Elisabet appeared, the story of the swan ladies launched like a photoelectric clash, suddenly and unexpectedly. The choice was not made with alert consciousness. Myth enchants me always.

“I was inspired by our contemporary times and the growing possibility of this world’s end. The story is told from some distance, from the future. It tells of events which happened in a world that no longer exists.”

3. Elisabet stumbles into the lives of these creatures, wandering into the plot–she seems both fascinated and distant from the modern life of the city. How do you navigate that dissonance? Were you at all inspired by the persona of the flâneur?

It’s strange for me to talk about Elisabet otherwise than as a character in a novel. The character is not at home in modern life, at the same time Elisabet uses her skills to provide for her living. She keeps the society she belongs to at bay; it brings her temptations that might hurt her – she claims; further details of mentioned temptations the story doesn’t comment upon. I was myself for years a persona of the flâneur, I used to walk for hours and those walks inspired at least two of my novels.

4. Something that stood out to me at the beginning of the book was how Elisabet and the swan-women find common ground in feeling alien and seemingly coming from nowhere. Would you be able to expand on the idea of home or lack thereof?

The feeling of being an outsider is perhaps a most common feeling? I wonder if that has been surveyed: how common it is. Perhaps one strives each and every day to fight against this feeling, striving for a fusion with the herd? To thrive in the act of belonging. For the swan-ladies the feeling is for real: they don’t own a home, they don’t own a story of origin, they don’t have a place, they are illegal beings. The novel lets its readers decide for themselves why Elisabet is not so at home with her society; the reasons might be diverse.

5. What is your relationship to place and story? Are there specific places you keep going back to in your writing?

Yes, there are, especially places from my childhood, apartments I visited. I have sometimes wondered: why do these places stick in my mind? But the people who lived there have left and the playground is ready for new inhabitants, fictive personas.

“My drawings become more and more connected to my writings; they often work as foresight for what I am soon to write about, thematically and sporadically. Literature influences my writings more than visual art, which frees my eyes.“

6. What was some feedback you received that was instrumental to honing your writing?

Definitely. Thank you for asking. I am not able at this moment to measure what has honed the most, perhaps due to timidity to face reality. Writing seems to be driven by an inner force similar to that which drives life itself. One does need to understand others perhaps more than oneself, not because life is a game-play, a chess, and one is fighting a game, no, no — and writing is not about fighting at all — but because the understanding blooms – enriches! — one’s inner life and shortens the distances. If something like oneself exists.

7. In what ways does being a multidisciplinary artist influence you?

I do not define myself as an artist, more I find myself — if I find myself — as a poet and an author. In visual arts I am a viewer, and I very much enjoy being an arts viewer; this is perhaps one of my favorite places in the world. My drawings become more and more connected to my writings; they often work as foresight for what I am soon to write about, thematically and sporadically. Literature influences my writings more than visual art, which frees my eyes.

8. To follow up, there’s something very theatrical about Swanfolk. Could you tell us a bit more about that?

I started as a playwright, I wrote 8 or 12 plays from the age of 23 to 49.

“I hope readers enjoy the book and deep down I wish for the similar experiences I have had from reading books: something in the brain moves and some inner happiness.”

9. According to Women in Translation, less than 31% of translations into English are written by women. Vala Thorodds, your translator, is the recipient of a PEN/Heim Translation Fund Grant and has translated your work before. Are you involved in the translation process at all? What do you hope readers across languages take away from Swanfolk?

Yes, I read Vala’s scripts and answered her questions and comments. Her approach to literature is beautiful, delicate, thorough and of utmost respect; so adorable. Vala is also a poet. I hope readers enjoy the book and deep down I wish for the similar experiences I have had from reading books: something in the brain moves and some inner happiness…

10. Who is a writer that you love that we might not know about? Are any women writers who have not yet been translated that should be on our radar?

Yes, for sure: Vigdís Grímsdóttir, from Iceland, Monika Fagerholm, from Finland and my late friend and teacher Álfrún Gunnlaugsdóttir.

Kristín Ómarsdóttir’s debut work was a play produced by The National Theater in Iceland in 1987. She has written plays, poems, short stories, and novels. Her most recent works are the novel, Svanafólkið (2019), published in English, Swanfolk (2022), and collection of short stories, Borg bróður míns (2021). Her literary work has received literary prizes and distinguished nominations, and has been published in Denmark, Finland, France, Sweden, the UK, and the US. Kristín writes and lives in Reykjavík.