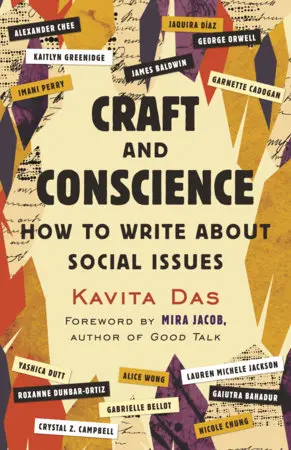

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America’s Literary Programs and Emerging Voices Program Director Jared Jackson speaks with Kavita Das, author of Craft and Conscience: How to Write About Social Issues (Beacon Press, 2022). Das’ book stresses the importance, hardships, and rewards of writing about social issues. Amazon, Bookshop

1. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

I believe both nonfiction and fiction can be truthful and conversely can be untruthful depending on the writer and their beliefs and motivations. So, I don’t believe that nonfiction alone is the terrain of truth. In fact, in Craft and Conscience I talk about how in journalism I believe there’s been too much focus on notions of neutrality rather than truth. Especially when it comes to issues of social justice, we need writing dedicated to uncovering the truth and guided by a sense of ethics rather than neutrality, which in itself is a fallacy because who is judging what is neutral especially when our mastheads and newsrooms are so woefully undiverse?

As a writer who has worked in social change and racial justice, I’m often motivated to reveal a truth about a social justice issue that is somehow obscured or overlooked. But just because I’m not neutral doesn’t mean that I don’t bring examples, evidence, and analysis to bear when illustrating the issue. And as a reader, I appreciate other writers who are dedicated to parsing social issues through a lens of justice and equity.

2. Your second book is Craft and Conscience: How to Write About Social Issues. What questions should writers consider when embarking on writing about social issues? Why is this an important starting point?

I begin Craft and Conscience by talking about the importance of understanding our motivations for writing about a social issue. Why do they want to write about this issue? What are their hopes and goals for writing about the issue? What are their fears and obstacles? In this first chapter I share 3 pieces, one by George Orwell, one by James Baldwin, and one by me, which speak to the writers’ motivations for writing about social issues.

I end the book by urging writers to examine the implications, positive and negative, of writing about social issues. In the writing world, we talk of ‘writing your truth’ or ‘speaking truth to power’ but we don’t talk nearly enough about the implications to others and ourselves of doing so. I believe it’s important for writers to consider these implications before their work is out in the world.

“This is why authoritarian, fascist forces at home and abroad target writers and the written word. They believe in the power of writers and the written word to topple them and yet we writers sometimes debate whether art is truly activism.”

3. Craft and Conscience: How to Write About Social Issues features texts by Kaitlyn Greenidge, Alexander Chee, and Lauren Michele Jackson, to name a few. How did you decide which writers to include in the book? What elements of their writing on social issues stood out to you?

The first six months I spent working on the book I focused on reading and selecting the writers and texts that I would include, including my own, that demonstrate how to effectively write about social issues in ways that resonate while doing justice to those issues. Each writer and piece I included showcases a specific lesson in the book but beyond this they caused me to think more deeply or differently about an issue, which is what I think the best writing does.

There were several authors whose work I admired and knew I wanted to include, including George Orwell’s “Why I Write,” because Orwell embodies a writer of conscience and this essay is a foundational text which interrogates a writer’s motivations for writing. I was also focused on gathering together a diverse array of voices, not just in terms of the identities of the writers but in terms of the range of issues they focused on and their approach to writing about them. In the cases of Jaquira Díaz and Garnette Cadogan, I included 2 essays by each on the same issue to how that it is possible for the same author to write about the same issue using different approaches.

I used twelve of my own essays so that I could provide readers with insights into my motivations and approach to writing about certain issues and the decisions I made in doing so.

4. What is the responsibility of the writer in times of unrest? How can writers affect resistance movements?

Writers are scribes and chroniclers of our times. Through their words and the worlds and characters they create, they hold up a mirror up to our society. They show us how our story will unfold if things continue as they are and they show us how the world might look when humanity is at its best or worst. So, during times of unrest, writers’ work is crucial to help create awareness of rising injustices and their implications to individuals and society. Writers have been crucial to recent social justice movements including #MeToo, #BlackLivesMatter – chronicling, analyzing, critiquing, parodying.

As awareness grows through the reach of writers and their work, so too does support for resistance movements working to remedy social injustices. And this is why authoritarian, fascist forces at home and abroad target writers and the written word. They believe in the power of writers and the written word to topple them and yet we writers sometimes debate whether art is truly activism.

5. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

Today’s book bans and attempted book bans on children’s books and youth literature focused on marginalized lives are deeply concerning and reveal much about the regressive, coercive society that conservative forces envision. Make no mistake, it’s an organized fight where regressive forces have taken over school board and educational oversight positions at the local level. This is a fight over not only freedom of expression but the very truth about our history and our present times and our children’s understanding of all of this.

But I also think these bans are a testament to the fact that reading and writing is activism – why would those forces be trying so hard to ban books if they didn’t believe in the power of words to open minds?

In truth, I know there are many writers around the world who have paid dearly for speaking out on and off the page, even some who have paid the ultimate price with their lives. So, anything I’ve experienced pales deeply in comparison. But I have worked in spaces that prohibited free-thinking and expression, that conducted themselves in complete contradiction to the principles of equity and empathy that they publicly professed. It’s particularly painful to work in social change organizations whose mission is to change the world for the better but who have created a toxic environment for the very people working hard to make that mission a reality. In one situation, I stood up for myself and others and had to resign and I was later told that leaders refused to acknowledge my existence after my departure, which contributed to low staff morale. I mention this because we don’t talk nearly enough about the toll of social change work.

“I’ve encountered people who are unhappy and uncomfortable with the revelations in my work but they are usually interested in maintaining the status quo and so therefore are not my target audience.“

6. You’ve taught at the New School and Catapult, among other settings. How did you set out on teaching not just the craft of writing, but about social issues in particular? What went into designing your course?

I semi-joke that I created my Writing About Social Issues class because it was the class I wish I had when I transitioned from working in social change to writing full-time. And with Craft and Conscience, I wrote the book I wish I had at that time.

Teaching the class grew out of my experience of working in social change and then writing about it. I had to learn from others and teach myself to adjust my perspective from one of a social change agent to that of a writer, from having a clear agenda to relying on my narrative craft to convey my perspective. During my transition, I read widely and identified writers, past and present, who wrote about social issues in ways that resonate while doing justice to the issues. And as I published more and varied work, from ideological essays and personal essays to reported pieces and op-eds, I created certain underpinning concepts to help guide my writing and realized, these might be helpful to other writers who were seeking to write about social issues. For example, for each piece I write, I have to understand what my motivations are for writing it, how much information I need to share and how to share it with the intended audience so that they understand the broader significance of the issue and its impact, decide if I want to write about it from a personal perspective or reported perspective, consider the implications of writing about this issue to others and myself, and ensure that I’m being culturally sensitive.

So, I created the Writing About Social Issues class 5 years ago and I’ve been so impressed by the passion of my students for crucial issues and the ways in which they engage them on and off the page. My students include academics, social change agents, and those directly impacted by issues, who hope to illustrate why a specific issue matters and sometimes offer potential actionable steps we can take as individuals or as a society. I’ve taught it as a six-week intensive class and as a semester-long nonfiction seminar at the New School.

After several years of teaching Writing About Social Issues in small cohorts, I wondered how I could offer these lessons and reflections to more writers grappling with writing about social issues and that’s how Craft and Conscience came to be.

7. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity?”

My various identities show up and shape my writing. My work in social change for close to 15 years on issues including housing inequities, health disparities, and racial injustice motivated me to continue to engage with these social issues when I became a writer.

As a South Asian American and child of immigrants born in this country, I feel drawn to understand these communities and my place in them while feeling simultaneously like both an outsider and an insider.

But ultimately, it’s my identity as a writer that compels me to try to understand myself and the world through writing.

8. What is the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

I’ve never written anything I wish I could take back because most of my pieces are guided by a sense of compassion, justice, and equity. When I came to writing from the racial justice space 10 years ago, I was truly appalled at the lack of diversity and equity in the literary and publishing realms and I didn’t understand why it was not being talked about more and openly.

This was especially true in the realm of biography, where the subjects, writers, and publishers were all woefully undiverse. Coming from laboring in racial justice and being at work on a biography of an overlooked woman of color artist, I felt compelled to write about these inequities and their ramifications on who and what gets published and I’m still proud of those essays and some are included in Craft and Conscience because I believe they are provocative while being measured and evidence-based. I’ve encountered people who are unhappy and uncomfortable with the revelations in my work but they are usually interested in maintaining the status quo and so therefore are not my target audience.

I do want to note that I was deeply disturbed by the recent brutal attack on Salman Rushdie, an author I admire. I’m grateful that he lived and for PEN America’s commitment to advocating for writers who are endangered by authoritarian forces. But it feels like many in the literary and publishing realm are tempted to view this incident as an isolated incidence of fanaticism while not paying attention to the rising climate of hostility towards writers whose work engage fraught social issues putting them at risk of harm.

“I strive to keep people and their hopes and dreams at the center of my writing and I believe that comes from my time working to improve peoples’ lives.”

9. You worked in social change for nearly 15 years. How has your experience in that sector affected your writing—your subject matter and how you approach it?

Having worked in the social change sector for 15 years, my work traversed social issues and even institutions, from bureaucratic government offices to well-heeled philanthropies to scrappy nonprofit organizations. I came to understand that social change is hard, takes time, and is often met with resistance from those who seek to keep society as it is. I’m not naturally a very patient person, but social change work has taught me to be patient, which was good preparation for writing, where inspiration might come quickly but revisions come much more slowly. Also, I’m a linear thinker yet both social change work and writing are often non-linear. I make a plan, an outline, but then I follow where the work or narrative takes me. Both have surprised me for the better and for the worse, which holds its own lessons. Both are about transformation, writing works at the individual level while most social change works to address systems.

Both social change work and writing are fundamentally about people. In social change work, you can get swept up in just focusing on systems and forget that those systems are made up of people who are either helping or hurting people. Similarly, in writing, you can create the most elaborate plot or structure for your story and lose sight of the fact that at its core, your story is about characters and how they speak to the reader through their words and actions. I strive to keep people and their hopes and dreams at the center of my writing and I believe that comes from my time working to improve peoples’ lives.

10. Why do you think people need stories?

I believe we need stories for two purposes – to make sense of the world and ourselves and to entertain and bring joy to ourselves. Some writing fulfills more of one purpose than the other but as I note in Craft and Conscience, ideally a writer can find a way to write about social issues in a way that is both compelling while doing justice to the issue, fulfilling both purposes that stories serve.

Kavita Das writes about culture, race, gender, and their intersections. Nominated for a Pushcart Prize, Kavita’s work has been published in WIRED, CNN, Teen Vogue, Catapult, Fast Company, Tin House, Longreads, The Atlantic, Los Angeles Review of Books, The Washington Post, Kenyon Review, NBC News Asian America, Guernica, Quartz, Colorlines, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. Kavita’s upcoming book Craft and Conscience: How to Write About Social Issues will be released by Beacon Press in October 2022 and was inspired by the Writing About Social Issues class she created and teaches. Her first book, Poignant Song: The Life and Music of Lakshmi Shankar, was published by Harper Collins India in 2019. She lives in New York with her husband, toddler, and hound. Find her on Twitter @kavitamix and Instragram @kavitadas