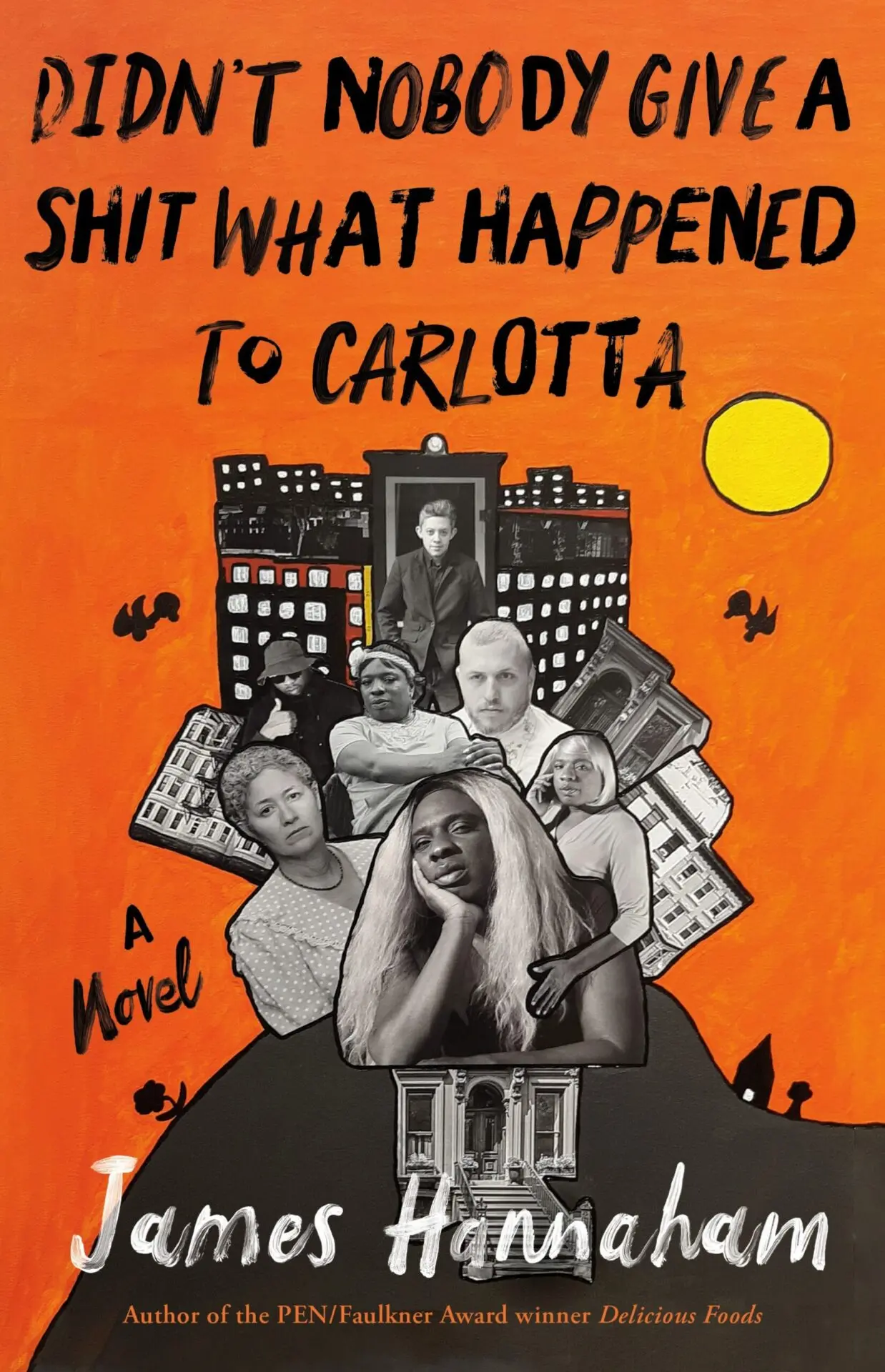

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America’s Community Outreach Manager Alejandro Heredia speaks with James Hannaham, author of Didn’t Nobody Give a Shit What Happened to Carlotta (Little, Brown 2022). Amazon, Bookshop.

1. Let’s start with the humor. Are you intentionally this funny? Does it just happen? I found myself laughing even in the most painful parts of Didn’t Nobody Give a Shit What Happened to Carlotta.

“Are you intentionally this funny?” is a question for someone like Udo Kier, whose vibe is so serious that it’s comical. I’ve always been trying to be funny, maybe since birth. A lot of my biggest influences are comic ones: Monty Python, Richard Pryor, Gershon Legman, Franklin Ajaye, Marsha Warfield—and OG SNL Head Writer Michael O’Donohue in particular, because of his faith in dangerous humor and his hatred of the false dichotomy between comedy and tragedy. Though he does not sound like the nicest man. For many years, my peers didn’t think I was funny at all. I suspected that my humor was just going over their heads. My family got all the jokes, but we were like OG blerds. Still, making a sophisticated joke was always worth it to me even if only one person in the room got it. Unfortunately, that one person was frequently me. Hopefully that is not so much the case anymore.

2. How was your research process in the creation of this novel?

Technically, the research started when I was a child, and my grandmother and aunts and cousins lived in a brownstone in Fort Greene that my grandfather bought in the 1950s (some of my cousins still live there). The research I did consciously for this book started a bit later; the word “process” makes it sound a lot more organized than it ever was. Focused, yes, but organized, not at all. I sometimes do research in the middle of writing a sentence. I mean, the Interwebs is right there, man! I read a boatload of books, interviewed people, read more books, went to websites, downloaded pamphlets, visited Colómbia, volunteered with organizations, read more books, watched movies, saw plays, read poems—what didn’t I do? Even all the gay clubbing I did in the 90s turned out to be research for this book. It’s like, I have no word for research. Life is research. I use what’s at hand. But I had always intended to show off some of my institutional knowledge of the New York Metro area with this book, because books about New York City are so overdone. But they don’t always acknowledge the kind of semi-demented street life I wanted to indulge.

“I’m not one to complain about lack of representation in the mainstream, because IDGAF. The mainstream ain’t shit. While it presents the illusion of equality, it really just represents the equal right to be degraded and disrespected in the mass media. The equal right to mediocrity. I know it helps people feel less alone. But marginalized people can find what we need without the interference of multinational corporations.”

3. So much of the novel details the gentrification of Brooklyn over the decades. Can you tell us a little bit about what’s being lost and/or gained as the neighborhood changes?

I wouldn’t hate gentrification as much if it could just freeze at that moment when there are enough higher income people (not all of them white, thank you, I’m not going to fall into that trap) for a pleasant mix of people where POC are still in the majority, the supermarkets improve (sometimes the prices in low-income areas aren’t any lower than the ones in the high-income supermarkets, and that feels like a variety of crime), a fancy wine store and a not-fancy one can coexist, and the West Indian restaurant owners haven’t fled. But the housing market is totally rapacious and unfortunately the dynamics of our country mean that there’s a kind of white flashover at a certain point. For Fort Greene, Black homeownership did slow that to some extent, but that flashover already happened at least 20 years ago. Now we’ve got these gigantic unaffordable high-rises filled with the white folks who wear the yellow sweaters on their shoulders, and the only new restaurants that survive are Italian ‘cause some people who shall remain nameless can’t deal with spicy, exotic cuisines. Or people.

4. When I was growing up, there was seemingly such little representation of Black LGBTQ literature in the mainstream. That’s changed a lot, especially in the last decade. How, if at all, do you feel Carlotta is in conversation with a lineage of Black LGBTQ literature?

That’s an interesting question. I mean, I’ve never been that interested in the mainstream, because the mainstream has never been interested in me. I could probably count on one hand the number of times there has been Black butch queen representation in the mainstream. That guy on Six Feet Under? Michael Sam? A couple of others? I don’t even bother to look. But I’m not one to complain about lack of representation in the mainstream, because IDGAF. The mainstream ain’t shit. While it presents the illusion of equality, it really just represents the equal right to be degraded and disrespected in the mass media. The equal right to mediocrity. I know it helps people feel less alone. But marginalized people can find what we need without the interference of multinational corporations. You’d think that would be preferable! As far as any direct connections, I think I quoted Essex Hemphill somewhere in the book, and maybe Assoto Saint? Those queens meant a lot to me—all those Tongues Untied brothas; Joseph Beam, Marlon Riggs himself—and Assoto was a truly amusing, sex-positive character in addition to breaking a lot of ground, so though I abhor all those like, dignity clichés everyone throws around like gospel, their impression was lasting. LEGENDARY! And technically there was a whole generation of artists and writers like those guys who just didn’t make it because of AIDS. They didn’t get the chance to break through. And before that, the Black LGBTQI+ writers who went mainstream had to bust out so undeniably that they necessarily influenced everyone: James Baldwin. Lorraine Hansbury. Langston Hughes. Countee Cullen.

5. There’s so much attention to music in the book! That scene with Rihanna’s song “Birthday Cake” is unforgettable! How did you come to select the songs? Are you considering dropping a playlist accompaniment soon?

It’s largely intuitive, so it’s true of everything I’ve written. As a kid, I was an AT40 sycophant, a musician—terrible at the clarinet and okay at the piano—a composer, and later, a music critic. Music is one of those things I have a wide range of experience with and that I can draw on pretty easily. It sticks in my memory really easily. Largehearted Boy asked me to do a musical breakdown for God Says No and Delicious Foods, but not this one yet. Some of those house tracks are only on the YouTubes, I think. Susan Clark’s Underground Diva mix of “Deeper,” for example, which is life itself. So maybe if I get a moment, I’ll do it, if someone asks.

“I am deeply concerned about social issues, but my allegiance is to art. Art tells me that life is ambiguous and weird and full of big questions with no answers, whereas activism tells me things like ‘You need to do this one thing now to save the world,’ and ‘We all have to be on the same exact page to get anything done.’”

6. What musician are you listening to right now?

7. What is a moment of frustration that you encountered in the writing process of this novel, and how did you overcome it?

One pivotal moment was when I realized that I was low-key rewriting The Odyssey. Upstate New York has a lot of towns named for classical literature, and so any story about someone coming back from an ordeal in upstate New York is by implication a retelling of The Odyssey. I knew I would have to acknowledge that in some way. But frustratingly, I also knew that everyone and her dog has used The Odyssey as source material, so it felt tired. That was around June of 2016, and coincidentally, my husband Brendan, who is of Irish descent and still knows his family back there, took me to Ireland that June (the joke was that now I had to take him to Africa, so we went to Cape Verde in December, a trip inspired a different book!). I brought a copy of Joyce’s Ulysses and ended up deciding to layer that in on top of The Odyssey. So the way I solved the problem was to make it ten times more of a problem.

8. How would you like your novel to be in conversation with social justice conversations?

I am deeply concerned about social issues, but my allegiance is to art. Art tells me that life is ambiguous and weird and full of big questions with no answers, whereas activism tells me things like “You need to do this one thing now to save the world,” and “We all have to be on the same exact page to get anything done.” So I’ve tried to make the book’s story reflect an artistic sensibility that contradicts all kinds of presumptions—even ones I believe in!—but also use it an occasion for activism. While the book has to stand on its own and say things that may or may not be useful for advocacy, and even offend people, I like to organize events and raise money and awareness about causes linked to the subject matter. With Delicious Foods, I created a relationship with an organization called Free the Slaves. This time I partnered with a group called Black & Pink, a prison abolition nonprofit that supports BIPOC prisoners and former prisoners. On the Dolly Parton tip, I quietly donated a big chunk of my book advances to each of these organizations.

“Don’t let a message get in the way of the truth, even when that truth is embarrassing, counterintuitive, or unpopular. I find myself increasingly bothered by people whose main message is to convince people of BIPOC humanity and, like, worthiness.”

9. What advice would you have for a writer who’s interested in addressing specific social justice issues in their creative work?

Don’t let a message get in the way of the truth, even when that truth is embarrassing, counterintuitive, or unpopular. I find myself increasingly bothered by people whose main message is to convince people of BIPOC humanity and, like, worthiness. First of all, who you talkin’ to? Not me, I been had known that shit. I take BIPOC humanity as a given! If you’re not on board with BIPOC humanity from the jump, I don’t got nothin’ to say to you! But I also don’t think there’s anything inherently dignified about being any type of human. It’s gross, a lot of it. It’s contradictory, it’s bizarre, it’s mysterious, it’s beautiful, it’s depraved, it’s tragicomic. It’s usually many of those things simultaneously. Ask yourself, how can I be faithful to the truth about existence and tell a story from the POV that best suits my argument about the world, whatever that is? How can I remain an independent thinker w/r/t those very things when everyone’s out there telling me what I should feel and say, and providing convenient, prepackaged language with which to say it?

10. Can you tell us a little bit about the audiobook for the novel? I heard you’re working with the amazing comedian Flame Monroe!

What a dream! Flame has an incredible drive that I admire so so so much. I thought it would be cool to collaborate with someone from the trans community on this project, and when I saw Flame’s standup, I could not believe how perfectly her (technically heshewe’s) sensibility fit Carlotta. I felt like Carlotta had fallen out of the sky in the flesh! Flame’s the right age, has the right kind of outspoken, edgy verve, and does not care what people think of heshewe. And fuuuuuunny as fuuuuuck! It’s hard to be that kind of pioneer, but heshewe is really up for the challenge. What I didn’t know is that heshewe’s experience was closer to Carlotta’s than I even realized—Flame’s had experience with the carceral system, and has three children to Carlotta’s one. I found all that out while sitting in a very small booth with Flame for 7 hours a day for a week, doing some of the hardest work either of us had ever done (I got sick in the middle of it, too!) to get the audiobook right, and actually having an absolute ball at the same time. Hopefully we brought the heat to that ball, dahling.

James Hannaham is a writer, a visual artist, or both. His novel Delicious Foods(Little, Brown 2015) won the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction, the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award, and was a New York Times Notable Book. He has shown work at Open Source Gallery, The Center for Emerging Visual Artists, and won Best in Show at Main Street Arts’ 2020 exhibit Biblio Spectaculum. In 2021, he released Pilot Impostor,a multigenre book inspired by a Fernando Pessoa anthology, to considerable acclaim. His third novel, Didn’t Nobody Give a Shit What Happened to Carlotta, arrived in August 2022.