The PEN Ten: An Interview with Eloisa Amezcua

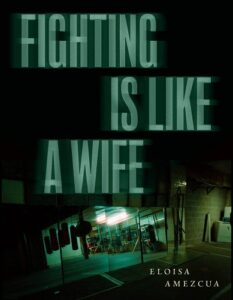

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America’s Literary Programs and World Voices Festival Coordinator Viviane Eng speaks with Eloisa Amezcua, author of Fighting Is Like a Wife (Coffee House Press 2022). Amazon, Bookshop.

1. Fighting is Like a Wife explores the love story and tragedy between pro boxer Bobby Chacon and his first wife Valorie Ginn. What first captivated you about their relationship, and what made you ultimately dedicate this collection to exploring it?

I was captivated by the tension between Bobby and his career, Bobby and Valorie, Valorie and Bobby’s career—everywhere I turned throughout my research, the tension was present, it grew and grew and grew. In writing the poems that would become the collection, I wasn’t looking to explain or to provide answers, so much as I was hoping to invoke this tension through language and form.

2. We most often learn about athletes in documentaries, biographies, or through memoirs. I’m curious about how you came to the decision to share Bobby and Valorie’s story with readers through the poetic form. What are some limitations that come with writing about a life, or lives, through poetry that might not occur through nonfiction? Conversely, what are the added freedoms, if any?

Well the easy answer to this question is that I don’t write nonfiction or know how to make documentaries (lol). But what drew me in to Bobby in particular was his use of language. He used really fascinating syntax and an almost circular logic when he spoke in interviews or was quoted in articles; there isn’t so much a point to what he says as there is a return. And there was something naturally poetic about that. And because I only write poems, it was either writing this story through poems or not writing it at all. One big limitation was knowing that I couldn’t include every single piece of information that I had gathered about Bobby and Valorie, especially given the formal constraints and parameters that I had set for myself (e.g. all of Bobby’s poems are composed of his own quotes, etc.). I was able to find the most sense of freedom in craft. Poems are not simply a way to communicate facts; they are a means of evocation, a summoning of emotion and memory and imagination.

“I wanted the experience of reading the book to feel as close to the experience of watching a fight as possible. For there to be momentum and rhythm and fluctuations.”

3. Your poems in the collection incorporate direct quotations from sports commentators and Bobby himself. What was the most interesting aspect of your research process? What’s something you learned that you perhaps didn’t expect?

My favorite aspect of the research process was watching and rewatching all of Bobby’s fight footage that I was able to find. I watched most of the fights in their entirety at least twice. The first time through, I’d watch and take notes on what I saw, the way their bodies moved, the pace and momentum. The second time through, I’d transcribe as much as I could of what the announcers were saying both during and between each round. One thing I noticed that I wasn’t expecting was how emotionally intertwined and invested the announcers were in the careers of the boxers whose fights they called. You can hear the emotion in their voices, the excitement and sadness and concern. At the end of Holmes v. Cobb in 1982, Howard Cosell, one of the most well-regarded sportscasters in American TV history, says, “What is achieved by such as this?” in response to the referee not stopping the one-sided fight. He never called a professional boxing match again after that night. Yes, there are politics and ethical considerations that went into that decision, but there is also love and fear and a desire to protect people, from each other and themselves.

4. Many of the poems throughout Fighting is Like a Wife utilize the literary device of repetition. Lines in poems often repeat themselves or replicate with subtle variations, almost akin to the repeated jabs one might experience in a boxing match. What effect did you hope the reader would pick up on when choosing to make repetition so front and center throughout the collection?

I wanted the experience of reading the book to feel as close to the experience of watching a fight as possible. For there to be momentum and rhythm and fluctuations.

5. It was so nice to work with you on the 2022 World Voices Festival, which you helped curate, alongside John Freeman, Devyani Saltzman, and Louise Steinman. What was it like to help bring a literary festival to life after two years of very limited in-person literary events? What types of authors and works did you and your co-curators hope to spotlight at this moment in time?

Being a curator for the 2022 WVF was truly a dream! Especially after two years of isolation and fear and uncertainty. Working towards something gave me hope and I think my co-curators and I really wanted to spotlight that sense of possibility, of acknowledging the difficulties we’d experienced, from the personal to the global, while rooting ourselves in the idea that literature and art matter, that people who write and create have something of value to share with us.

“I think it’s important as writers to remind ourselves that we have an active role in defining the world around us, in shaping the spaces we inhabit and move through or between, and in uplifting the voices that represent who we are and who we hope to become.”

6. What are some of your favorite writers working today?

This is truly an impossible question but because they give me so much life, I will say my colleagues at Randolph College. There are too many incredible names to list here but spending ten days with these writers twice a year and listening to them at the nightly readings (often sharing works in-progress) or sitting in on their lectures has been life-changing for my creative work and my being.

This is truly an impossible question but because they give me so much life, I will say my colleagues at Randolph College. There are too many incredible names to list here but spending ten days with these writers twice a year and listening to them at the nightly readings (often sharing works in-progress) or sitting in on their lectures has been life-changing for my creative work and my being.

7. If you could claim one writer, living or dead, as part of your literary genealogy, who would you pick? If you could share a meal with them, what would you hope to discuss?

My paternal grandfather wrote poetry. A few years ago, my dad gave me his father’s archive: notebooks, typewritten pages, poems in newspaper clippings. My grandpa wasn’t around much when I was a child and died when I was in middle school so I never knew him well but I feel like I know a part of him through his writing. I’d hope to talk about his writing, of course, but also about him—his life, his work as a doctor, his favorite movies, everything.

8. How can writers affect resistance movements?

I think it’s important as writers to remind ourselves that we have an active role in defining the world around us, in shaping the spaces we inhabit and move through or between, and in uplifting the voices that represent who we are and who we hope to become. Audre Lorde said, “Poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought.” SO IT CAN BE THOUGHT! That’s it, right? In order to affect anything, we must think it possible first.

“For me, poetry is a medium where language serves its most rudimentary function: to define, to communicate. Poetry uses language to investigate the self and the world around us, not in search of any particular answer, but to illuminate what is, what has been, and what could be.”

9. What are you working on next?

I recently learned how to make paper! The workshop started with us chopping down tree branches (mulberry and fig) all the way to drying individual sheets. I got my finished paper in the mail (it takes a few days to fully dry) and almost cried when I touched it. Anyways this doesn’t answer your question except to say that I hope to continue working on papermaking and stuff-making and writing poems. There’s nothing specific I’m working on (that I feel ready to talk about) right now 😉

10. In times of crisis—whether they involve war, grief, or pandemics—many people turn to poetry for comfort. Why do you think that is? What poets do you read when you’re feeling lacking in hope?

For me, poetry is a medium where language serves its most rudimentary function: to define, to communicate. Poetry uses language to investigate the self and the world around us, not in search of any particular answer, but to illuminate what is, what has been, and what could be. I think there is comfort in that interrogation and in knowing that someone else is also trying to make sense of…everything, while admitting that language can only do so much.

When I find myself hopeless, I turn to the work of Wisława Szymborska, Joanna Klink, Raúl Zurita, M. NourbeSe Philip, Nicanor Parra, Layli Long Soldier, Octavio Paz, Olena Kalytiak Davis, Don Mee Choi, Diane Seuss, my incredible friends—not because I am searching for hope necessarily, but because I am hoping to remember what is possible with language.

Eloisa Amezcua is from Arizona. She is the author of Fighting Is Like a Wife, published by Coffee House Press in April 2022, and From the Inside Quietly (2018), inaugural winner of the Shelterbelt Poetry Prize selected by Ada Limón. A MacDowell fellow, Amezcua’s poems and translations are published in New York Times Magazine, Poetry Magazine, Kenyon Review, Gulf Coast, and others. She is the Associate Director of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America and serves on the faculty of Randolph College’s MFA program.