The PEN Ten: An Interview with Chinelo Okparanta

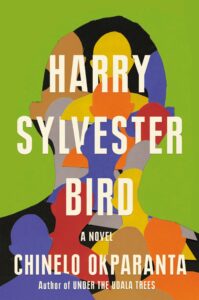

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America’s Literary Programs and World Voices Festival Coordinator Viviane Eng speaks with Chinelo Okparanta, author of Harry Sylvester Bird (Mariner Books 2022). Amazon, Bookshop

1. At what age did you realize that you wanted to be a writer? What are some factors that influenced this decision?

When I was around 10 or 11 years old, I won a citywide essay contest in Boston that helped me build confidence in my writing abilities. In high school, I won at least one other notable contest. Years later, in college I took some creative writing classes, in both English and French. After graduation, I became a secondary education teacher first in New York City, and then in Allentown, PA, where I led an after-school creative writing club. For my master’s degree, I also took some creative writing classes, though my primary focus (i.e. my thesis examination) was on the Restoration Era (17th and 18th century British Literature). It wasn’t until attending the Iowa Writers’ Workshop from 2009 to 2011 that I began seriously pursuing a career in writing. Before that, my primary training was in the field of education.

2. What is a book that you find yourself returning to often? Are there new takeaways you glean each time?

Oh, I go back to so many books at random times in my life. Recently, I re-read Albert Camus’ The Stranger and Voltaire’s Candide, simply because I felt that my most recent novel, Harry Sylvester Bird, had some similarities to those books, and I wanted to refresh my memory of those books. Other novels I’ve gone back to several times in the last few years are Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye (I go back to this one quite often for the beauty of its prose and for the racial and sociopolitical weight of the story), Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping, Mariama Bâ’s So Long A Letter, Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go (I also loved Klara and the Sun), and two stories from Octavia Butler’s Bloodchild—“Bloodchild” and “The Book of Martha.” I teach these last two stories for my writing sci-fi, fantasy, and other worlds course, and I’m just always amazed by how much worldbuilding skill it takes to write a good sci-fi fantasy story.

“As a Black, African, woman writer, there’s also a certain pigeonholing that occurs—I’m theoretically only supposed to write certain narratives: about female sexuality, about female suffering, about romance, about failed love and failed marriages, about motherhood, about African governmental corruption, about the general African condition.”

3. You were born and raised in Nigeria, but spent your university years and beyond in the US. How does your personal history influence the types of stories you’re interested in creating? Are there certain places that you constantly return to in your writing?

Actually, my immediate family immigrated to the United States when I was ten years old, which means that I began living in the United States well before my university years. That being said, I’ve gone back home to Nigeria for brief stays throughout the years. Being both a Nigerian and United States citizen has given me insight into the two cultures from an insider’s perspective and from an outsider’s perspective, because I am both an insider and an outsider in both contexts.

Where my writing is concerned, I’ve written stories set in various places in Nigeria (Lagos, Port-Harcourt, Ojoto, for instance). I’ve also written stories set in different cities in the United States (Philadelphia, Boston, New York, Iowa City, Washington, DC, for instance), all of which I’ve actually lived in for substantial amounts of time. I find that my stories in general have a strong emphasis on geographical place. I take my time to make sure that my setting is clear, perhaps because if I am a bit nonstationary via my peripatetic lifestyle, then let me at least be grounded in place, where my fiction is concerned.

But if you mean place as a non-geographical point in space, then I’m also interested in writing stories about physical and psychological belonging. Under the Udala Trees is a novel about societal ostracization by virtue of one’s sexuality and how one creates one’s own self-worth and one’s own community. Harry Sylvester Bird is also about the difficulties of finding one’s place in a very unstable, racially tense, and fiery society. In some small ways, it is in conversation with Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye. In Harry’s case, it’s not a story about a girl seeking to be white. It is instead about a young man seeking to be Black. Just as Morrison’s Pecola sees having blue eyes as a mark of beauty, Harry believes himself to be Black African and sees Black Africanness as the sought-after race. Of course, the historical contexts for both characters are incredibly different, Pecola’s particular circumstance is far more dire and painful than Harry’s, and the genres of the novels are also different, so in many ways the two characters and the two novels are also not comparable at all.

4. Harry Sylvester Bird chronicles the coming of age of the eponymous Harry, a youngster who detests his racist and generally unbearable parents. Later in his life, Harry falls in love with a Nigerian woman and adopts a new Black persona in solidarity—blurring the lines between appreciation and appropriation, and leading him to confront his whiteness in new ways. What inspired you to bring someone like Harry to life?

In early 2016, I’d been teaching a course on the ethics of writing other cultures at Columbia University, and then that summer, I moved to a pretty conservative part of Pennsylvania. This was during the period that Donald Trump was taking over office. It was a time when many people felt free to speak their minds, to be openly racist and discriminatory. I really appreciated the candor—it’s always good to know where you stand in such circumstances. Better the enemy you know than the enemy you don’t, that sort of thing. As you can imagine, I had many very interesting race-related incidents in a place like that, and at a time like that, and all of these really informed Harry Sylvester Bird and led to my creation of the character of Harry. Harry is actually, at times, quite empathetic. Essentially, I wanted to satirically explore the character of a well-intentioned white liberal from within, but also from without, because I am, after all, not a well-intentioned white liberal but have had to endure many of those “well-intentioned” offenses as a Black woman and as a Black African immigrant. That being said, Harry is clearly a satirical rendition of said well-intentioned white liberal, as hopefully no one actual individual embodies all of his faux-pas at once.

I’ll add that I was wary of writing the story as a satire, because I know that many satirical novels with heavy sociopolitical critique were historically difficult to publish, or upon publication, poorly received, at least at the onset, or sometimes ignored. For instance, Candide, Animal Farm, Brave New World, and more. I also knew that satire is not only a tricky beast to write, it is also a tricky genre for some readers to grasp. There are also different kinds of satire, and not everybody clicks with every manifestation of the genre. One must often sit with it to understand all the nuances that the work has to offer. It’s always easy to look at the work superficially, and satire can often come off as superficial, but a devoted reader will hopefully keep in mind that, in satire, context matters. History matters. The contemporary politics of the day matter—and in a manner that is more than meets the eye.

As a Black, African, woman writer, there’s also a certain pigeonholing that occurs—I’m theoretically only supposed to write certain narratives: about female sexuality, about female suffering, about romance, about failed love and failed marriages, about motherhood, about African governmental corruption, about the general African condition, etc. Those sorts of topics. And in fact, I’ve written some of those stories too. There’s nothing wrong with those stories. The issue comes when reading audiences don’t know what to do with your work when you deviate from the script. So, in that sense, writing Harry Sylvester Bird was also a risk.

Regardless of the risk, fundamentally, writing the novel was a calling. This time, I wasn’t called to write a novel that focused on all the expected topics about being African and/or a woman. I was called to write a novel that speaks to some Black and Black African-in-America experiences of racism and racial microaggressions in a way that hadn’t been done before. The point of entry into the novel is not conventional given that I enter via a white man’s POV. But he is a white man who identifies as Black African, and as an African, I felt that I could engage more effectively in a narrative like that. Harry, the protagonist, also has a Nigerian girlfriend, who helped to inform Harry’s character as well. I could portray him by way of her experience of him. And as a Nigerian woman, I knew I had some insight into the kinds of situations she would find herself in where Harry was concerned, and therefore, some of the kinds of situations he would find himself in. In any case, this is the first book I’ve written that delves completely into the Black/ Black African experience of racial prejudices in America (albeit from the lens of a fictional white character who identifies as a Black African man, as written, of course, by me, a Black African woman). Which is to say that this would also be the first novel I’ve written (or read) that experiments with those specific layers of characterization and narration. This approach, by my lights, best unveils the different levels on which racism and white supremacy have been known to operate.

5. The book opens with three epigraphs, the latter of which is attributed to Dr. Bayo Akomolafe: “What if the ways we respond to crisis is part of the crisis?” Why did you choose to frame the book using this quote? What are some ways you feel it applies to our current social and political landscape today, especially when it comes to issues related to race?

I found the quote by Bayo Akomolafe very intriguing when I first came across it. My use of it was simultaneously an agreement with it, but also an interrogation of it. There’s a thing my grandmother once said a few years before she passed. We were all gathered together in Lagos, many of my cousins, aunts, uncles, and more, all of us having a good time. But at some point, the festivities must have gotten overwhelming, because my grandmother called us to her. She was blind at the time, and she said, “So much noise. Everybody just keeps talking, but nobody is listening.” It has stayed with me since. Sometimes it does indeed feel like everybody is talking and no one is really listening. What would it take for us to stop all our talking and just listen? What would that look like? We are a world that values outspokenness and having a voice, and that is a wonderful thing. But what to do when there’s just too much noise and everyone has lost the ability to listen, to really hear one another, to really hear the other side? Silence gives us this opportunity to hear the other side, an opportunity to empathize with others. If we are all talking at the same time, our ability to listen and empathize is compromised. There is a difference between choosing to be silent versus allowing ourselves to be silenced. We can still speak, and we can still take action with just a little more space for a pause. Because, what if all our impetuous responses to all our crises are only fueling the fire? I don’t know if longer moments of silence will actually yield the results we seek, but what I know is that sometimes, there’s a place for silence, or at least, there should be.

But then, even after the silence, even after the expressions of empathy, what happens when, still, there are serious, baffling setbacks that continue to endanger the welfare and lives of certain disenfranchised groups (as is the case with racial situations at times)? In those cases, I tend to agree with Toni Morrison—“This is precisely the time when artists need to go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear….” In those cases, it is the artist’s duty to call the oppressors out on their oppression. Though, if I’m being honest, I’ll say that, as an artist, perhaps unlike Toni Morrison, I do have fear as I call out these injustices, and I often must make every effort not to let my fear get in the way of the art that I’m being called to create.

“Silence gives us this opportunity to hear the other side, an opportunity to empathize with others. If we are all talking at the same time, our ability to listen and empathize is compromised.”

6. You are the recipient of two Lambda Literary Awards and an O. Henry, among others! How has the recognition from awards programs affected the way you think about your work and your identity as a writer?

I’m grateful for the recognitions from such institutions as Lambda, Hurston Wright, NAACP, the Caine Prize, Etisalat, O. Henry, the NYPL Young Lions, the Rolex Mentor and Protégé Initiative, Dublin, as well as from writing and artist communities such as Civitella, Hedgebrook, and many others, because they affirm and celebrate who I am as a person and as an artist. It’s a wonderful thing to be part of communities of supportive and truly progressive minded people who are able to see the social significance of my work. These recognitions also mean that my work is reaching the audiences who matter to me most. Still, art is a calling. I know that I have to be willing to do the work I am called to do whether or not there are prizes.

I’m grateful for the recognitions from such institutions as Lambda, Hurston Wright, NAACP, the Caine Prize, Etisalat, O. Henry, the NYPL Young Lions, the Rolex Mentor and Protégé Initiative, Dublin, as well as from writing and artist communities such as Civitella, Hedgebrook, and many others, because they affirm and celebrate who I am as a person and as an artist. It’s a wonderful thing to be part of communities of supportive and truly progressive minded people who are able to see the social significance of my work. These recognitions also mean that my work is reaching the audiences who matter to me most. Still, art is a calling. I know that I have to be willing to do the work I am called to do whether or not there are prizes.

7. You’ve also been on the other side of awards judging—including being on a panel of judges for PEN America’s Open Book Award. What was that experience like?

Being on a panel of judges for a national (and international) award is an incredible opportunity to immerse oneself in the current year’s literary output. I’ve thoroughly enjoyed the chance to serve on several judging panels and to read incredible works of literature by both seasoned and debut writers. But I won’t lie, it takes quite a bit of focus and dedication. Reading so many books in such a brief period of time is definitely a lot of work!

8. As the director of the creative writing program at Swarthmore College, you must interface with young writers quite a bit. What’s something that you always try to impart on to your students, whether it be craft related or not?

A student came to me explaining that he really felt that his calling was to be a fiction writer (He had just won the college-wide fiction contest). But, you see, his mother would be disappointed in him. There were rules she had, and he felt obligated to follow her rules. He asked for my thoughts. I gave him the same advice I gave to students in my fiction workshops: There are rules to everything. There are rules to good writing. It’s a wonderful thing to learn the rules, and to learn them well. Only by learning them can you learn the clever ways to break them. Sometimes you’ll inevitably fail. Other times you’ll succeed. But always, you’ll learn something new.

“There are rules to everything. There are rules to good writing. It’s a wonderful thing to learn the rules, and to learn them well. Only by learning them can you learn the clever ways to break them.”

9. What’s something that your readers might find surprising about you?

A friend of mine, Lori, recently told me about a conversation she had with another friend, in which they were discussing my most recent novel, Harry Sylvester Bird. Lori’s friend had said something to the effect of Harry Sylvester Bird being quite a departure from my usual style. To which Lori responded, “Not really.” Because, of course, Lori has known me for what feels like ages. And she knows that I have a background in satirical literature, not just contemporary but also historical.

As I said earlier, I earned my master’s degree in English Literature with a focus on 17th and 18th century British literature (The Restoration), so, in addition to my background in the field of creative writing, I also have a pretty strong British (Restoration era) literary background. That particular period of English literature was actually quite fun to study, as it includes a lot of bawdy and satirical works of literature, such as Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels and “A Modest Proposal,” Fielding’s Tom Jones, and many more. I also studied French literature as a teenager, including Voltaire’s Candide. Swift was critical of English high society in general and their abusive treatment of the lower classes; Voltaire was critical of European aristocracy and its philosophies at the time, as well as of the church. I was taken by the boldness of these works, and I’ve been interested in satire since—going on to read more contemporary satirical works by authors such as Aldous Huxley and George Orwell, Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five, Paul Beatty’s The Sellout. There’s also Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah’s Friday Black, a collection of short stories of which some are, like Harry Sylvester Bird, biting satirical explorations of racism in contemporary America. There are many other contemporary satirical novels: Less by Andrew Sean Greer and Severance by Ling Ma, for instance.

Another surprising thing about me: I love ice cream, which I don’t think ever features in my writing. Recently, I discovered Jeni’s Splendid Ice Creams, which immediately caught my attention because Jeni’s ice creams are made with grass-grazed milk and contain no synthetic additives. Also, Jeni’s is a certified B corporation which means that it adheres to very strict social and environmental standards. I love my junk food, but I like to think that I’m still eating it cleanly, you know, soiling my stomach responsibly. My favorite Jeni’s flavors are Salty Caramel and High Five Candy Bar.

10. What are you reading now? What’s next on your list?

I recently read Dolen Perkins-Valdez’s Take My Hand, one of the most beautiful and most important books I’ve read in the recent past. I’m looking very much forward to reading Mohsin Hamid’s The Last White Man.

Chinelo Okparanta’s debut story collection, Happiness, Like Water, and her debut novel, Under the Udala Trees, have won and been nominated for numerous awards. She’s been published in The New Yorker, Tin House, and elsewhere, and was named one of Granta’s Best of Young American Novelists.