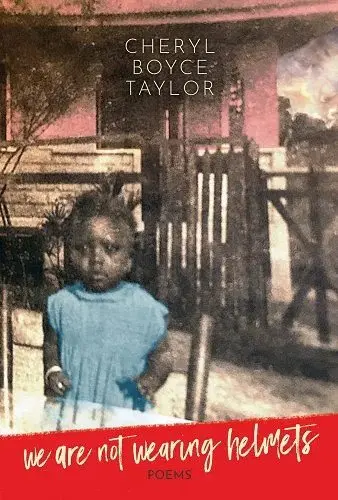

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America’s Director, Prison and Justice Writing Caits Meissner speaks with Cheryl Boyce-Taylor, author of We Are Not Wearing Helmets: Poems (TriQuarterly, 2022). Amazon, Bookshop.

1. The book starts with a small and mighty poem that begins with “The day they killed Martin / we could not return to New York City.” This doorway into the collection does so much work: it places us in the context of a generation-shaping event that placed us in the author’s personal and political timeframe, and, I think, it alerts us that this book will be addressing the current climate through the lens of the past. Maybe I am inventing here. Either way, it’s a terribly powerful choice. Tell me about choosing to start the book with this poem.

In this collection, I begin with the Martin Luther King Jr. poem because it stands as a marker as to how my life changed drastically when he was murdered. I was a seventeen-year-old high school senior on my way to Huntsville, Alabama on my first college tour. As young adults, my classmates and I felt so grown up being away from our parents for the first time.

We had planned a weekend of fun and dancing. Then suddenly our world blew up. We felt a sinking terror almost like the end of the world. I felt the same kind of terror when Trump was elected. Suddenly we were at war and amongst the many ways I knew how to fight, I turned to my pen. This opening poem represents our current times of hate and racism. It is a very frightening time. As a teenage girl, I began fighting for my rights and freedom, and here I was, forty-four years later still fighting for myself and seniors in my community. It is so painful to feel like nothing much had changed.

2. As a woman acculturated, as we all are, to repress our anger, I was tickled, delighted and nearly shouting aloud at so many moments where you just let anger rip in these poems! Moments in childhood of trying on the propellant and benefit of anger, the liberating anger of an elder who no longer gives a shit, the honest expression of anger at a long term partner, and of course, anger at the political climate then and now. I selfishly want to know: what helped you develop this open expression of beautiful rage—were you always this bold?

Honestly, I have to credit my father for my use of anger. Growing up my parents lived apart from each other. Sometimes shuttling between them got pretty frustrating. My father would agree to pick me up so my mother could attend an appointment. Then, for whatever reason, he would be late or say he forgot. Often by the time he arrived, it was bedtime. My mother was often displeased by this and so was I. Generally, by the time he picked me up I was not speaking to him. Rather than getting mad, he encouraged me to tell him why I was upset. He allowed me to cry when tears came but asked me to say what I was really feeling. There were times I told him off. Yet rather than shut me up, he listened. He never scolded me for my childish outbursts. He let me know, by example, that it was okay to voice annoyance and anger and do so without recrimination. I will always thank him for those lessons. These are the same lessons I eventually passed down to my son about anger. My father raised me in a non-gendered way teaching me to speak up for myself, something unheard of in a 1950s Caribbean daughter. I was always this bold and forward, except for a short period in ninth grade when I first arrived in New York City and was sad and unsure of myself. I know how to be loving and kind, but I know how to equally be a harsh loudmouth to defend myself.

How can anger function successfully in a poem?

Anger opens doors to honesty, truthfulness, forgiveness, as well as self-acceptance. These are some of the main keys to great writing.

“I write about childhood to hold on to those strong and loving years when I first became aware of language, image, and performance.”

3. Time in this book operates in a very moving way. We begin in the 1960s, move into the present, then back to childhood in Trinidad, then into the lingering impact of writers who came before, then to recent love— it allows the intersection of your identities to fully unfold and cross hatch: poet, mother, daughter, immigrant from Trinidad, mother, daughter, Black woman in America. Tell me about putting this collection together. How did you determine the sections? The movement? The flow? The overarching message? The interconnectivity of personal and political?

The book begins during my migration in the 1960s when I moved from Trinidad to America. Trinidad was a nation of mostly people of color. My teachers, doctors, neighbors, ministers, best friends, and family were mostly black or of Chinese or Indian descent. There absolutely was some prejudice and issues of color, but it was mostly between the adults. Once in New York City, I did not see much representation of myself in movies or television, and when I did, it was mostly in degrading roles. This made me very sad, I felt like an outcast, not beautiful, smart, important, or deserving of a great life. Then I became angry that I felt inferior. It was during that time that I decided I had to write in dialect to remember the rich and colorful culture I came from. I had brought pride and dignity with me to the United States. I was not going to leave it behind. Poet, daughter, immigrant, proud black mother in America… that’s who I am. I write about childhood to hold on to those strong and loving years when I first became aware of language, image, and performance.

I was a daughter who slept in bed with her mother from the day I was born until I left at the age of thirteen. I slept with her partly because we didn’t have an extra bed in the home, and because my mother was an early helicopter mom. Her most precious possession was her girl. She was going to give me everything that she had not had coming from a family of nine girls and two boys. My mom describes that time as getting lost in her family. There were way too many children to care for. She never got a chance to feel special. She was not going to repeat that experience with me.

In this collection, I speak not as an artist but as an observer, participant, and resident seeking radical change to create a better world and safer planet. Additionally, I set out to honor women artists that came before me. I’ve seen them fight and survive. I know what has to be done to save myself and the community. I refuse to beg for substandard living, healthcare, and housing. Instead, I demand personal rights and the rights of my people. As Audre Lorde says: “the personal is political, it’s all one fight.”

4. The Zuihitsu is a form I learned from you—“follow the brush”—and one that feels simply made for your work. The flexibility of the form is able to hold everything a brain must balance simultaneously: fragments of memory, inspiration, the present moment, the collision of awake and asleep, conscious and subconscious. It also seems to me a really powerful form to play with the collapsed and expanded timelines that come with grieving. There is only one named Zuihitsu in this particular book, but I’ve read so many from you in other texts that make my heart race. What got you hooked to Zuihitsus, and what do they allow you to do that other forms don’t?

I fell in love with the poetic writing form called Zuihitsu when I studied with the Japanese-American poet Kimiko Hahn. It is a lyrical essay-poem form translated as the running brush. It is loosely connected by fragments of poems, journal entries, list poems, essays, letters, and overheard conversations among other things. I love the form because it is a naming of my life, which includes places I have been, places I want to go, dreams, altars, and issues that relate to the writer’s surroundings. Zuihitsu gives me a style and fresh freedom to run with language and time, to call into being images, words, and magical realism. It mirrors a gritty world and the fantasies found there.

5. Across this book you call out to your many poetry mentors, on the page and in real life: Maya Angelou, June Jordan, Ntosake Shange, Lucille Clifton, and Adrienne Rich. There is a tremendous multi-page tribute to Audre Lorde, who mentored you in real time, saw your possibility, called you in. Of course, many in our community feel that you’ve been this support for them (including me!) Tell me about mentorship on and off the page, and how mentorship has functioned in your own creative journey—as both mentor and mentee.

I grew up in an extended family household that set the tone for mentoring and supporting each other. We were taught to function as one unit where the adults worked, cooked, and cleaned, and the children picked up after themselves.

Our school, church, and community function similarly. For example, my grandmother was an untrained medicine woman. If there was someone in the community giving birth and complications arose, a neighbor or family member ran to get my grandmother. She quickly picked her garden herbs and went to assist with the birth. We children were pretty young at the time, but we were pleased to find out that the baby had been born without incident. If someone died in the community everybody cooked, chipped in money, and brought flowers, clothing, or anything to ease the family’s burden of burial and sorrow.

I believe that mentoring and nurturing happen in the same orbit. When I mentor a person or community, I offer knowledge, honesty, encouragement, and confidence. And alongside this, intention geared towards making their artistic vision sharper, more intentional, more abundant, organic, and satisfying.

Finally, joint mentoring becomes a tool for community health and wellness. It has the capacity to create pathways for harmonious living.

“I knew when I grew up I wanted to work in the service of story, memory, and community. Each poem is a prayer, each poem is an ancestral altar, a promise to the land, a vision I want to always hold, and never lose.“

6. On the heels of that question, I’m reminiscing about that reading in a Brooklyn church so many years ago when you grabbed my hand and welcomed me into the intergenerational women’s writing group (I’m the baby!), named after your mother, Elma. For years and years now we’ve written 30 poems in 30 days during National Poetry Month in April, and sometimes otherwise. I found it incredibly satisfying to see many poems from those early drafts in this book, wearing their best clothes! What does the act of communal creation do for you? What is the journey of a poem from that first draft to the pages of this published book?

Making art with others is a spiritual practice in love and faith. It is often difficult to know where it would lead, but the joy of it is opening up yourself and being grateful and satisfied with whatever fruit grows there. Making poems with Elma’s Heart Circle (named after my mother) is a practice in sisterhood. It offers a connection to the community. It is prayer, it is meditation, it is ancestral, and it is the ultimate way to clearer communication and intimacy.

Some poems fall out almost done. And some are unusable. But mostly, each usable poem takes weeks and months to birth and reveal itself. In my writing practice, I spend a lot of time deciding what the chosen poem is saying to me. Is the poem speaking to others? If so, what eventually is the good message I want to leave in the world? Sometimes a poem is not ready to reveal itself. In those instances, I go on spiritual obedience. I allow the poem to speak for itself.

7. you fill the corners / of each room with bitter bright marigolds / Mexican flowers for your dead.

— From “You Braid Your Hair”

This book comes after the publication of Mama Phife Represents, a gutting and healing memoir of your life with your son Malik (also known to the world as Phife Dawg from legendary hip hop group, A Tribe Called Quest), who passed in 2016. Given that I know your mother passed away years before, I was surprised and moved in this book to discover a section of beautiful praise poems dedicated to your late mother. It reminded me that grief is not linear, and we will all be addressing our grief and raising the dead for years to come in our work. As you know, I wrote in our group through the entire journey of my mother’s illness into her death. Your grief poems often taught me, and held me. Talk to me about writing grief—about poems and their possibility for healing: what they can do, what they can’t do, why you do it anyway.

In grief writing, there is honor, freedom, and celebration.

Honor, which allows you to honor the life and spirit of the beloved that has left us.

Freedom, which allows sorrow and heartache to pass from us, thus creating new pathways for healing and educating.

Celebration, which affords a relearning about the gift you were given by having this great love in your life.

I became an expert in grief poems after my son left us. I learned in that first year when grief took me back through his birth and life, how lucky I was to receive the greatest gift I have ever been given. I was reminded of the years of joy and challenges we rode together and how beautifully we made it to the end. It was the earth saying: this is a reminder of your lifetime gift, never forget it. The same was true when my mother died. At the time I believed there was not much reason to live. Finally, I embraced it, especially since I knew she was ready to go she had expressed it so many times.

I feel so lucky to have both of their guidance. They walk with me each day, side by side. They are always near. And this ultimately brings me the greatest sense of freedom. As Audre Lorde once told me, “acceptance is the greatest joy of all.”

8. Reading through the book, I notice how often fruit, fish, mango, spices, flowers and other delicious treasures and trinkets fill your poems. I see them as sensory memory locators, little hints that paint a scene, but also, treats worthy of praise, it seems to me. It makes each poem feel like a form of altar. Here is a sampling of such items scattered across the poems:

tamarind Jarritos

half-eaten cigars

bread & red candles

vanilla egg creams

plums

blue shell

lemon verbana

onions in the yard

pink pomerac and dark Chablis

white tulips

white sage

wild African bark strawberry tea

the bones of small goats

chocolate mint

heirloom tomatoes

cinnamon oil

horny goat weed

spiced Jersey beets

garlic knots

Tiger Balm

Sometimes I realize I don’t even notice such motifs in my own work until someone else points them out! Are you aware of this? I suspect yes. Tell me about these magical ingredients, a part of your signature poetic voice, and how they function in your work.

Each poem feels like an altar because it is. I worship each poem like an ancestor, a prized memory. Living in New York City, I never want to forget the beauty of my Trinidad. When I list items, places, and precious objects in a poem, it takes me back to a time when life was carefree and uncomplicated. I recall the first woman I ever saw in the marketplace balancing a large basket of fruit on her head. I was eight. This woman was there to provide for her family. She was there to sell, buy, and barter, but also to share her bounty with others. I noticed how she threw in a few extra pieces of fruit in a child’s basket or how she let a mother and her child taste some fish before they bought the tiniest piece but she sent them away with a big hug and a smile. This was an act of kindness and generosity. Later, these memories would become gems for poems. I noticed how she walked away with pride. She left a snapshot of elegance in my child’s eyes, a message about the dignity of employment and community. I knew when I grew up I wanted to work in the service of story, memory, and community. Each poem is a prayer, each poem is an ancestral altar, a promise to the land, a vision I want to always hold, and never lose.

The naming of objects helps me to stay grounded in my Trinidadian roots, the use of dialect keeps my grandmother’s voice attached to the red Arima dust of my birth. I am always a part of my land that holds my twin brother’s naval string. I am the half-eaten cigar thrown from the fat hands of a scary police officer with a bulging gun in his belt. I am white sage, round bread, and red candles sold on the shelves near the cash register in the Green street market. I am pink pomeracs, brown spice, silver bangles, colorful fabric, and dark Chablis.

I hear the market lady chanting them as she walks up and down the sidewalk. Her tone is so sensual. I always want to keep sensuality in my poems, in my life, and in my body. These are the markers that make up the journey of my life.

“It has always been my intention to give my readers truth and offer them permission to be truthful without judgment in their own lives and work.”

9. This is a sneaky question because I already know the answer, but I want to share it with others, too. Tell us about your writing rituals—the sensory and the sensual!

In my sensual and sensory writing, I am trying to capture a pleasurable memory or experience I once enjoyed. I am also attempting to recapture and engage the reader’s own experience of joy, longing, and celebration through touch, image, sight, sound, and memory. I try to write every day. When I am not writing, I am thinking about writing. On the days that I write I rise early at about four a.m. It is the quietest hour of the day when my spirit sings the loudest, the sassiest, and the most melodious.

10. There is an entire section in the book dedicated to your lover of over two decades! I find these poems to be so brave and honest and sexy. They map the real deal of being in long term partnership, both the ecstasy and the pain. I’m curious, how do you negotiate this level of sharing one’s private life with your partner? Do you ever get into hot water? How do you work through this? What are the ethics of writing about our loved ones, a common question in poetry and memoir specifically, through your perspective?

By the time I met Ceni I was already an out woman writing sensual and sexual poems. I never had to negotiate my content because she knew that we were monogamous, and that memory and fantasy lived in my work. I am certain that sometimes I go too far because she is way more private and conservative than I am, yet she takes it in stride. I’ve never gotten into hot water since she does not always read my final drafts. Discretion, honesty, and compromise are the ethics I use when writing about loved ones.

11. Though this poem, “The Home You Left Long Ago,” is dedicated to our friend Aracelis, I can’t help but think that this opening stanza feels like you, Cheryl, what you’re giving readers:

There is a moment

when you don’t even realize you are hungry

then a poet stands before you

a poet exquisite her mouth a topaz city

filled with hummingbirds, blue herons and marigolds

This opening stanza reflects my writing style for sure. At my age, there is nothing to hide. I have been publishing my work for over thirty years… it is all found there. It has always been my intention to give my readers truth and offer them permission to be truthful without judgment in their own lives and work. In my poetry, I share my whole self… the side that is vulnerable, silly, biased, or sneaky, the side that is afraid, grieving, joyful, sexual, loud, and sensual.

I’m often skeptical that poetry can save us. It feels so stale and incomplete an idea, but you, time and again, have made me reconsider and choose to believe. Give me another moment when poetry saved you. When you didn’t realize you were hungry, and then…

Poetry is always saving my life. It held me after my divorce from an eighteen-year relationship. It saved me after I left Trinidad without my parents and family. On those nights I recited my mother’s favorite poems like they were prayers. Poetry comforted me when I lost my mother and became a blanket to wrap me in when my son passed. I am uncertain of how I would cope with these challenges of everyday life had I not had poetry. It was on a night when I was reciting poetry at a work event that I met my partner. Up to that moment I was content being unhitched. But there she was tickled by my erotic poetry… laughing and making me laugh. I soon realized that I was hungry and that she in her silly way was there to feed me laughter, the food of the Gods.

Cheryl Boyce-Taylor is the winner of the 2022 Publishing Triangle’s Audre Lorde Award for Lesbian Poetry for her verse memoir, Mama Phife Represents, which stands as a tribute to her late son, hip hop icon Malik “Phife Dawg” Taylor of A Tribe Called Quest. Additionally, she is the author of five collections of poetry, Raw Air, Night When Moon Follows, Convincing the Body, Arrival, and We Are Not Wearing Helmets published by Northwestern University Press in February 2022. Cheryl has facilitated poetry workshops for Cave Canem, Poets & Writers, Poets House and The Caribbean Literary and Cultural Center.

Her poetry has been commissioned by The Joyce Theater and the National Endowment for the Arts for Ronald K. Brown: Evidence, A Dance Company. A VONA fellow, her work has been published in Poetry, Prairie Schooner, Aloud: Voices from the Nuyorican Poets Cafe, Revolutionary Mothering, One Breath Rising and The Mom Egg Review. The recipient of the Barnes & Noble Writers for Writers Award, she is the founder and curator of the Calypso Muse Reading Series. Cheryl earned an MFA in Poetry from Stonecoast: The University of Southern Maine, and an MSW from Fordham University. Her life papers and portfolio are stored at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.