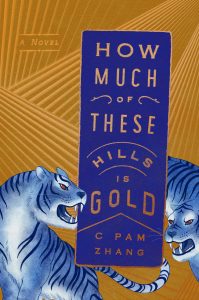

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Jared Jackson speaks with C Pam Zhang, author of How Much of These Hills Is Gold (Riverhead Books, 2020).

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

My first language wasn’t English. Shortly after moving to the states, I spent a chunk of my life copying by hand, every evening, the text of a series of children’s books that my mom assigned to me. I don’t remember the name of the series, which depicted a dog, kids with generic names like Jane, and adventures including one about a Gordian knot. The books were oddly large, their pages thin, and their color palette muted. This forgotten series is part of the scaffolding of my English.

2. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

I can divide my intellectual life into three stages: the child stage in which I didn’t know what was true, the young adult stage in which I believed I knew or could learn the truth of things, and the current stage in which I know truth is a slippery and impossible thing to define. I used to believe in objectivity from certain institutions—the classroom, for example. Now I know how politicized facts and numbers are, and how what is included or obscured is determined by people in power to further their own agendas. At its best, fiction can cut through the noise. It can tell an emotional truth more powerful than fact.

“At its best, fiction can cut through the noise. It can tell an emotional truth more powerful than fact.”

3. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

My creative process is built around the understanding that I require fallow periods. We must divest from the cult of productivity! The way we divvy up time is a capitalist notion. Why must time be apportioned into weeks, days, and hours, so that as one unit ends, we measure our work and feel inadequate for having failed to complete some allotment of tasks? In my few and privileged experiences at writing residencies, I learned that my creative process works best when untethered from the usual sense of time. That’s a long way of saying that I have substantial periods during which I don’t put a single word to paper. I’m letting my mind replenish itself, so that when I do return to the page, what’s pent up explodes outward.

4. What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know about?

Joyas Voladoras by Brian Doyle. Despite descriptions of my work as brutal, ferocious, or bleak, I am sappy at heart.

5. How can writers affect resistance movements?

Good writing makes possible something that didn’t previously exist. Resistance movements do the same; the first step in both cases is to imagine past the boundaries of what we’re told is permitted. Some of the greatest imaginations I’ve encountered are in science fiction writers and in activists.

“Good writing makes possible something that didn’t previously exist. Resistance movements do the same; the first step in both cases is to imagine past the boundaries of what we’re told is permitted.”

6. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity?”

I simultaneously never want to be asked this question again, and know it is my responsibility to consider this question again and again.

On the one hand, it’s exhausting to see this question disproportionately put to marginalized writers. The implication is that our work is less imaginative, more dully autobiographical because it is shaped by identity. Brandon Taylor, in his PEN Ten interview, spoke so eloquently about this that I won’t have to.

On the other hand, this is the world we live in. It’s impossible to move through life without feeling the million barbs and snags, the strange frictions that erupt between my identity, and the assumptions of the white male canon. For years, I tried to pretend my identity didn’t inflect my writing, and as a result wrote far too many bad “Imitation White Man” stories. In these stories, I didn’t want to name the race of my characters so that they could be seen as “neutral;” I refused to delineate my characters’ financial hardships. The vacuous work I created during this period was the worst option. If I must live in a world in which I regularly grapple with how my identity shapes me, then the most honest thing I can do is to commit that grappling to the page. At least for now. I hope to one day move past this.

7. What advice do you have for young writers?

Write into what is most frightening in your work. Write toward what makes your heart beat faster and your palms sweat, what sets off in you such a confusing cacophony that you must—like the dumb protagonist of a horror movie—walk down the basement steps to investigate even, and especially, if you are terrified of doing so. Within that uncertainty lives the most you part of your writing. The rest, anyone else can do.

8. In the first section of your debut novel How Much of These Hills is Gold, the reader learns of two deaths, Ba (who dies in the night) and Ma (who is long gone), which jump starts the novel. Can you speak to grief, and also legacy, and how they can equally be a detriment to and a catalyst for action? As the novel unfolds, how did the different relationships your two main characters, Lucy and Sam, had with their parents inform future choices and decisions?

8. In the first section of your debut novel How Much of These Hills is Gold, the reader learns of two deaths, Ba (who dies in the night) and Ma (who is long gone), which jump starts the novel. Can you speak to grief, and also legacy, and how they can equally be a detriment to and a catalyst for action? As the novel unfolds, how did the different relationships your two main characters, Lucy and Sam, had with their parents inform future choices and decisions?

I don’t think about grief as either detriment or catalyst; it is neither good nor bad. It simply is. The death of a parent is a black hole that warps time and space around it, after it, and before it; there is no escaping its effect. What is most dangerous for Lucy and Sam is that they pretend they can creep out from under the shadow of grief. By refusing to address it, they only create a cycle in which it visits again and again.

9. The novel, set near the end of the American Gold Rush, plays with gender identity and assumed roles, particularly with its character Sam, who, though makes astute choices to hide their sex—wearing a bandana to hide the lack of an Adam’s apple—never appears to struggle with it. How would you describe the significance of this detail in the novel, specifically given the era—mid 19th century and the outlaw nature of the American West?

I’m inordinately proud of Sam. Sometimes, when writing, you are given the gift of transcending your own limits; that’s Sam. Sam knows who they are, which is not to say that Sam is perfect. And yet, any concessions Sam makes are because they understand that the world is weak, broken, or strange—not because Sam is. The most daringly outlaw aspect of Sam’s nature is not that Sam shoots a gun or steals a horse. Sam trusts their own internal compass. People like this have always existed. It has nothing to do with time, place, or genre.

“If I must live in a world in which I regularly grapple with how my identity shapes me, then the most honest thing I can do is to commit that grappling to the page. At least for now.”

10. A focus of the novel is the notion of home, and at one point poses the beautiful idea between the difference of claiming land and being claimed by it. As an author who has lived in many places, what does home mean to you? How did you wish to question the meaning of home while writing the novel?

When I wrote the first draft of this novel, I had just moved across the world and didn’t know where I would end up geographically. I lived in a bath of uncertainty. I still don’t know where I’ll end up, but the uncertainty has calmed because I’m more at peace with the fact that I may never find a geographical home, if home is a sensation of complete belonging. Perhaps others can find that in a place, but I’ve yet to identify a city where—as someone who looks the way I look, dresses the way I dress, speaks the languages I speak, and holds the beliefs I believe—I don’t bump up against other people’s wrongful expectations. So, my sense of home has contracted somewhat, often meaning just a few people, a particular room, one bench in a park, or one restaurant.

Born in Beijing but mostly an artifact of the United States, C Pam Zhang has lived in thirteen cities across four countries and is still looking for home. She has been awarded support from Tin House, Bread Loaf, Aspen Words, and elsewhere, and currently lives in San Francisco.