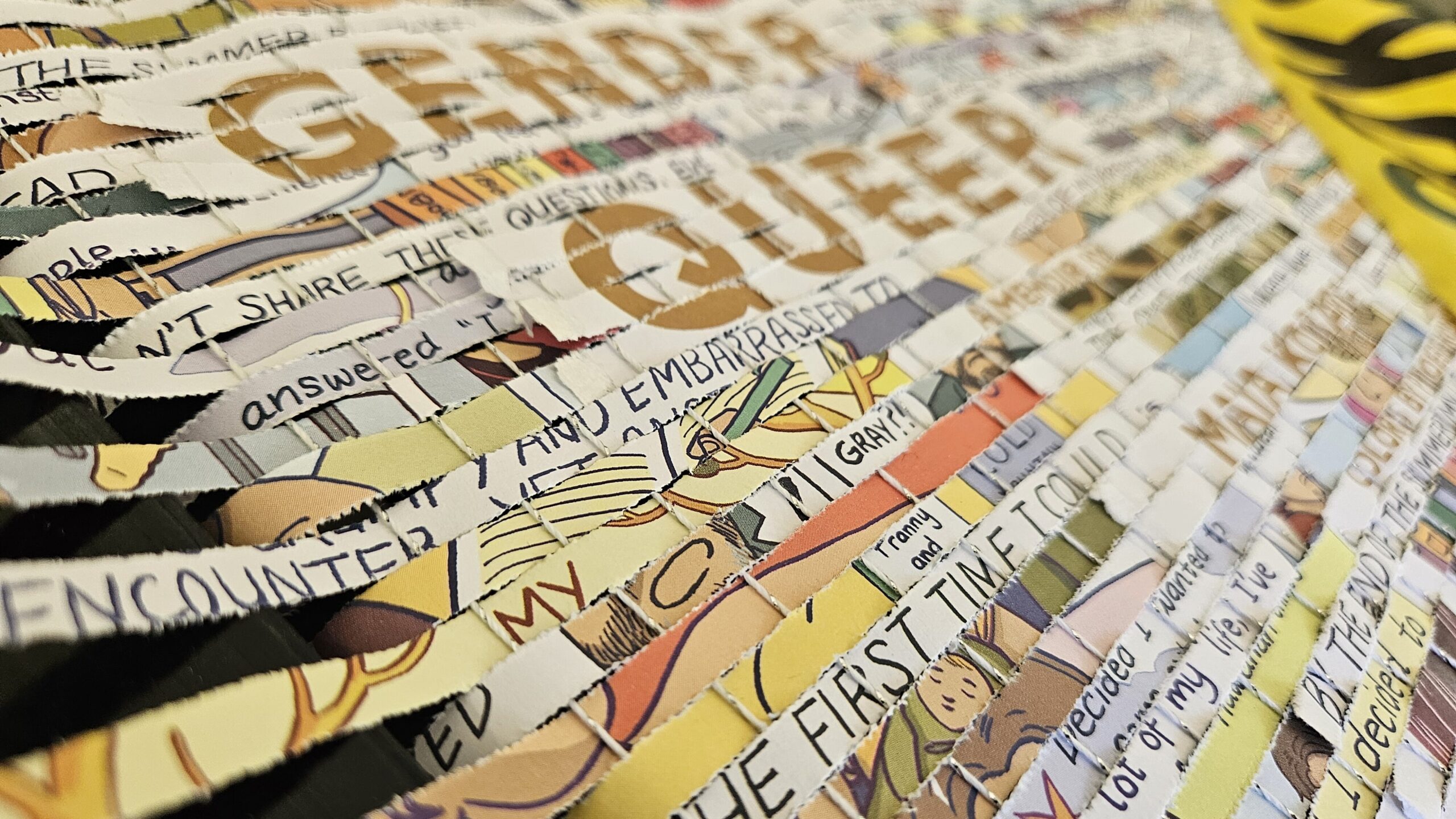

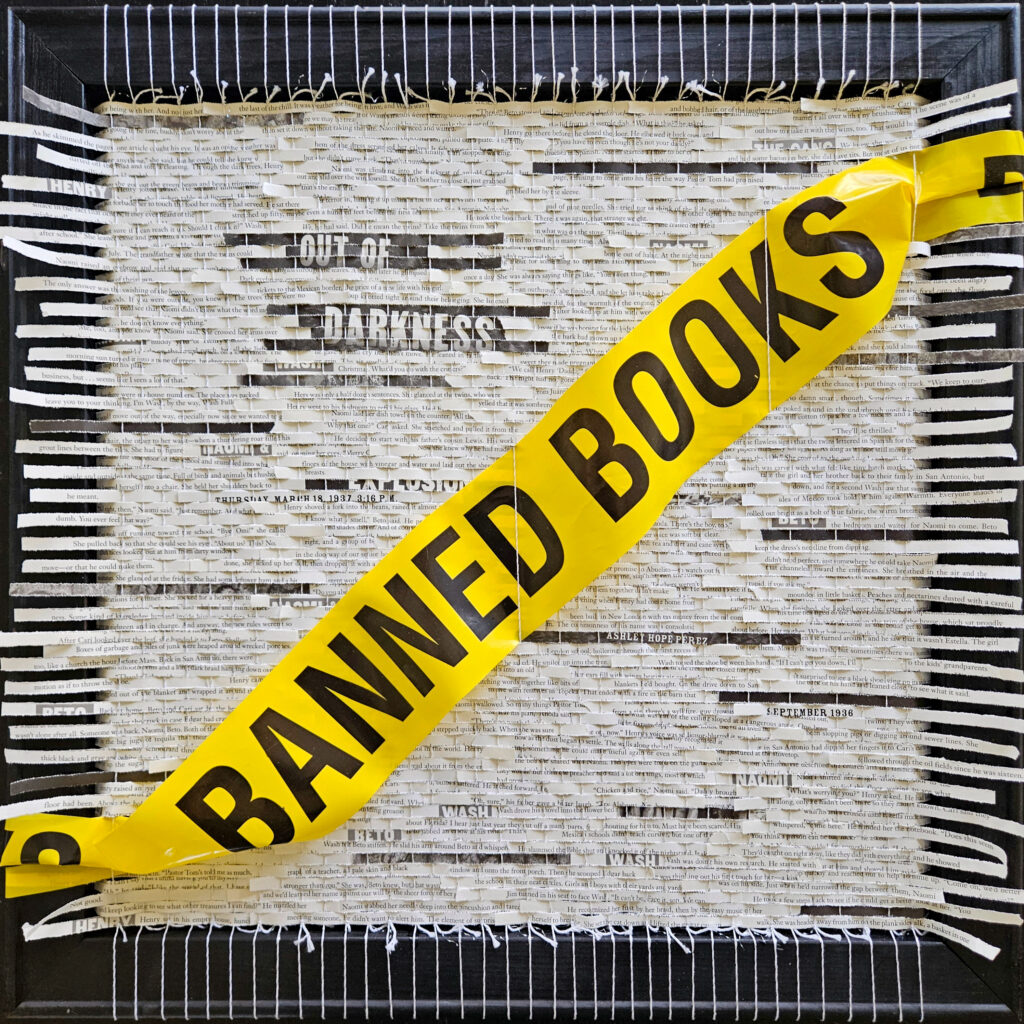

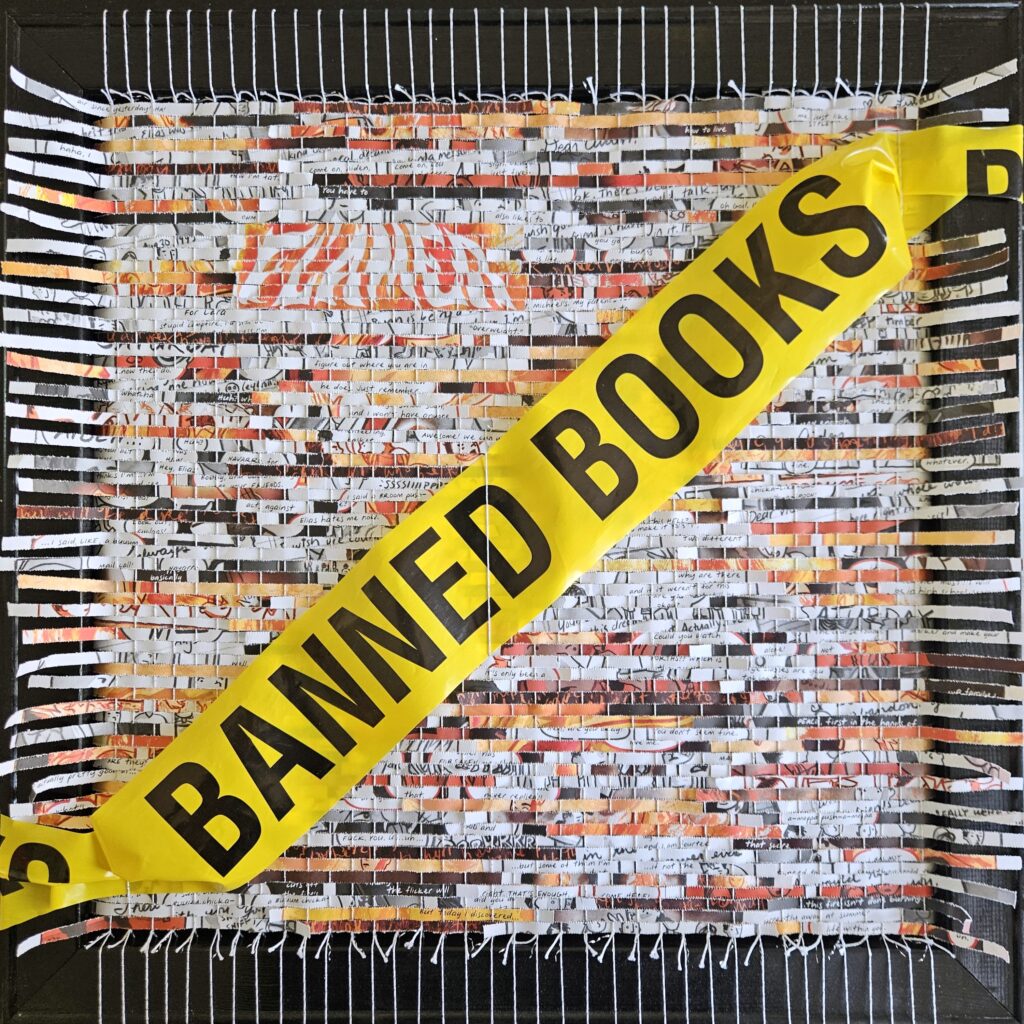

This fall, Artist Ellis Angel’s latest weaving series, The Censor’s Cut: Weavings for Intellectual Freedom, did not hang in a gallery or an art fair, but at a bookstore in Tulsa, Oklahoma. At Magic City Books, titles including A Court of Mist and Fury, Gender Queer, Flamer, and The Perks of Being a Wallflower, did not just sit on shelves but hung transformed–all shredded and rewoven, with the bright yellow “Banned Books” tape plastered across their backs.

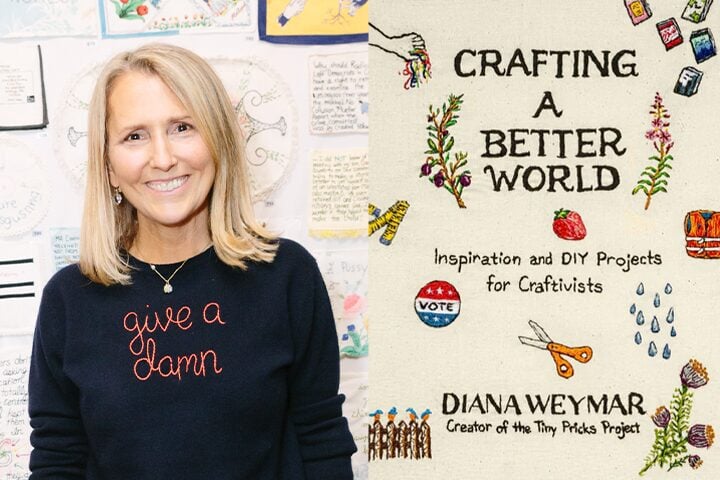

Angel, an artist and activist, envisioned the project after being enraged by the growing number of book bans across the country–in its latest report PEN America counted over 10,000 instances. The installation was put up at Magic City Books as a part of Banned Books Week 2024 and will be on view through Nov. 24. In an interview, Angel discussed a passion for political art, the weaving process, and the influence of censorship.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you get into art and what inspired you to create politically driven weavings?

I’ve always been inclined to make art. I think that it was probably a good coping mechanism growing up. But I really got into political work back in 2018 with the Women’s March. After that particular March, I started collecting posters that were just discarded along the street. I didn’t know what I wanted to do with them. I saw this frame as I was walking home into New York, and they were in pieces. And so the light bulb kind of went off from there. I took this big old thing home and I worked it up. For me, weaving is a way to dismantle and reconstruct texts—whether it’s the Constitution, currency, or the text of books, particularly those that have been banned. By using these materials, I’m able to comment on power, inequality, and the structures that uphold them. It’s kind of born out of this anger you don’t know what to do with, so you make something with your hands.

What role do books play in your life and what role do you believe artists have in combating censorship?

I’ve always loved reading, and I’ve always just wanted to learn more. I have a Masters in English, so books have always played a big role in my life and having other voices broadens your world in ways that the everyday cannot. There’s no replacement for it. So to have those voices silenced or censored is just appalling to me, and it’s something that fuels the fire to get me activated to do something in whatever way that I can. I believe that when we talk about artists, it encompasses much more than just visual artists. Writers, illustrators, and creators of all kinds have a responsibility to make good art, regardless of the pushback they might face. Censorship tries to stifle creativity, but it’s crucial that artists remain bold and true to their work, as we are exercising our fundamental constitutional rights. With the banned books series, my goal is to lift these authors and their works—their ideas—up, not drag them down. In times like these, we need to support each other and stand together in the fight for free expression.

Can you tell us more about ‘The Censor’s Cut’ exhibition?

The Censor’s Cut: Weavings for Intellectual Freedom is an exhibition that directly responds to the ongoing censorship by radical organizations and the conservative fight to ban books in America. As PEN America says, “The freedom to read is under assault like never before.” It seems crazy to me that in 2024 we’re still having this conversation—where groups like Moms for Liberty are fighting to remove texts from libraries—but here we are. The weavings in this show incorporate books from the ALA’s Top 10 Most Challenged Books lists of 2022 and 2023, as well as banned book caution tape. The goal is to make a clear statement that censorship is harmful and wrong. It silences important voices, particularly those from marginalized communities, and restricts intellectual freedom—something that we must all fight to protect. I don’t know who said it first, but I wholly agree that art doesn’t exist to make you feel comfortable.

By transforming these banned books into art, I’m forcing people to confront uncomfortable truths—about censorship, silencing, and whose voices are being erased.

Can you explain the process of creating one of your weavings?

The process usually starts with something that I’m mad about—something I want to change. The materials I choose are the things most dear to me, things I believe have value. For example, in Article I, I literally put my money where my mouth is by shredding real dollar bills to protest corruption and the influence of money in politics. With the banned books series, I wove with something even more valuable than money—books—to protest the censorship and silencing of largely marginalized voices. I gathered the books, shredded each book, and rebound them by weaving each one on its own frame behind banned book tape. You may not be able to read the text, or understand which book it is just from looking at it, but I provide that information with the title of the weaving. By cutting these materials apart and reweaving them, I’m inviting the viewer to pause, reflect on the meaning of the text, and turn that reflection into action. Maybe the book can’t slap back against the haters, the censors, but maybe my art can!

How did you feel when you exhibited your pieces not in an art gallery or fair but in a bookstore?

That’s a fabulous full circle. It sounds kind of corny, but it’s getting woven back in. When I made these, there’s no way I could have known where it would end up. I have spent the past year working on the banned book series, and it is particularly dear to me. I am overjoyed to be collaborating with PEN America to show these works for the first time at Magic City Books in Tulsa, Oklahoma. What better place to show them than with like-minded leaders in the fight for the freedom to read?

Honestly, I hope the audience takes one look at these weavings and it makes them sick.

How do you see your art influencing conversations around censorship? And in what ways do you think the rise of book bans will impact future generations?

I’ve always wanted my work to push the bounds of weaving—almost like Shepard Fairey meets Anni Albers. Weaving has traditionally been seen as quiet, often categorized as “women’s work.” But I’m taking the expectation of quietness and the functionality of craft and flipping it on its head. These weavings are not useful for anything other than their political commentary and place as protest art. By transforming these banned books into art, I’m forcing people to confront uncomfortable truths—about censorship, silencing, and whose voices are being erased. I hope that by transforming these banned books into art, I’m sparking conversations about why these stories are under attack and encouraging people to push back. Art has always been a vehicle for change, and my work is part of that tradition, challenging viewers to defend the freedom to read and resist the forces of censorship. If we don’t fight now for the freedom to read, then the expression of ideas, then we are doing a disservice to the next generation. And the fight is now, it’s not for later and it’s not for our children to bear. And it’s something that historically, we’ve always had to deal with. This is not anything new, but the activism by some of these organizations is really problematic and something that we need to address. The voices of a few should not be the end all for the rest of us.

How do you hope audiences will respond to your work? And how do you want to look back on your art?

Honestly, I hope the audience takes one look at these weavings and it makes them sick. The idea of ripping up books, of shredding these texts and what they represent . . . I want the audience to feel something. I want them to feel worry—that these texts can be banned and silenced. I want them to feel activated—that they need to make a difference. I want them to read the additional resources, like following PEN America’s link to email their legislators. And I want them to engage—register to vote, research who in their area is the best advocate for them, and get involved in their own community to make a difference. And I hope that one day these will be so just irrelevant and I could look back at these and be like, well, that was a different time, wasn’t it? I would love that so much. As John Lewis said, “Make Good Trouble.” Maybe one person can’t make a change, but if we all make a little good trouble, we can be a force for good.