Most journalists, not only those working on disinformation-related beats, are likely to confront disinformation and other manipulation tactics designed to amplify falsehoods and diminish trust in factual reporting. Journalists can even unwittingly become part of the problem.

The term disinformation can have many meanings depending on the user and context, but we define it this way: false information disseminated with the intent to deceive.

Disinformation has been around for a long time and has been employed by a range of bad actors. As communication technology advances, disinformation tactics are advancing, too. In the age of generative artificial intelligence, it’s critical that journalists and the public know how disinformation spreads, what its potential effects are, and how to recognize it.

This explainer, using a fictional scenario, covers several dynamics facing journalists, even though not all disinformation campaigns will include all of these elements. Here are eight common steps disinformers use to distribute falsehoods to the public, according to the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, a nonprofit dedicated to slowing polarization, extremism, and disinformation worldwide.

How Social Media Accounts Introduce and Spread Fictitious Claims

1. The disinformation source establishes a following, gains trust

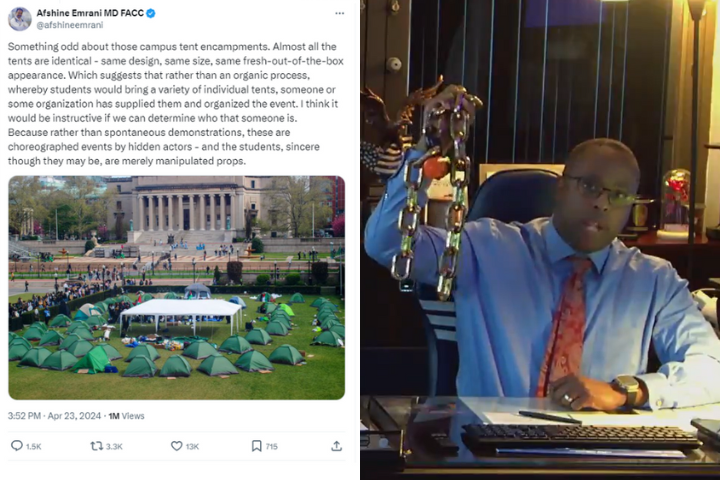

Disinformers leverage social media platform features and manipulate viewers’ emotions to help their narratives spread. Our example is a fictional scenario in which an anonymous account introduces and spreads unsubstantiated claims about an elected official. The original author leverages social media platform features to hide their identity and spread disinformation – even using a journalist as a conduit.

In this fictional example, @CleanGovWarrior has a blue checkmark, indicating it’s a paid and verified account on social media platform X, formerly known as Twitter. The account is known for calling out corruption and advocating for transparency from public officials. The account posts screenshots of genuine news articles and engages with high-profile figures, and has been retweeted by a handful of anti-establishment elected officials.

These are examples of two elements we often see from disinformers: The first is a focus on a universal value, because who doesn’t support rooting out public corruption? The second is interacting with accounts belonging to high-profile and often trustworthy figures. Both tactics help the account grow its following and establish it in its followers’ eyes as an authoritative, unbiased source, even though it is anonymously run and doesn’t have a clear affiliation with trusted sources of information.

2. The disinformer builds a cross-platform audience

A small group of Facebook accounts regularly share @CleanGovWarrior’s high-performing X posts on Facebook, while some posts are referenced on TikTok and Instagram, building an audience across platforms to amplify the message. This is particularly important because most Americans don’t spend much time on X but do use these other platforms frequently.

We don’t know whether the Facebook accounts spreading screenshots are real people, but they are acting in a suspiciously coordinated way. This is a common tactic and is extremely difficult for the average Facebook user to detect – they may reasonably assume a post in a group they are in is coming from a peer and be more likely to trust the claims in it.

Regardless of whether those accounts that initially share the posts on Facebook are real, they get the attention of real users, including activists who have politically engaged audiences.

How Disinformers Leverage Social Media and Emotions to Spread Their Narratives

We’ve explained how a bad actor lays the groundwork for a disinformation campaign. Here’s how disinformation is conceived and spread.

3. Seeding a disinformation narrative with a kernel of truth and evocative, unfounded claims:

Continuing with our fictional example, @CleanGovWarrior posts a claim about corruption in the county clerk’s office. The post is accompanied by an audio clip purportedly of a voicemail the clerk left for a cybersecurity firm CEO and screenshots of genuine-looking databases of the county’s procurement records, including contracts with the cybersecurity firm.

In the post, @CleanGovWarrior promises that more evidence will follow.

4. Spread to mainstream spaces:

This is where the disinformation campaign begins, with claims of a corrupt local official working behind the scenes with a local business executive.

The post purports to provide direct evidence of corruption, but the most important thing is that the claim is believable, stating something that many Americans assume is already happening in government. Finally, the promise of more evidence to come provides the air of a conspiracy and creates anticipation.

5. Online organizing leads to offline action:

Responses to the post are quick to claim that the recording and database screenshot are proof of election tampering. On Facebook, the post is shared in neighborhood news groups. Commenters suggest organizing a group to show up at the county council meeting the following day.

Questions about the alleged corruption are asked during a county council meeting, bringing the initial social media post into the real world and forcing government officials to respond.

The Role of News Reporters in Covering Disinformation Campaigns Responsibly

6. Professional reporter platforms unfounded accusations:

As the events move from social media platforms to a local government meeting, the increased spotlight can begin to attract the attention of the news media.

At the council meeting, tensions rise as residents demand answers. Unsure where the question is coming from and unprepared to respond to it, the chairperson dismisses the question as off-topic. A heated exchange follows as local news outlets cover the tension.

7. Covering the controversy:

That night, television news includes a segment about the council meeting, including a clip from the interview, during which the questioner recites the corruption claims and demands accountability from local officials.

The reporter notes that the claims surfaced online in a post from an anonymous user claiming to have information from a whistleblower, with public records to back up the claims, but does not fact check the claim or investigate who is behind @CleanGovWarrior.

The reporter in this fictional example made mistakes. For one, the reporter did what we often call “covering the controversy” – an event like a heated council meeting that might seem newsworthy because of the conflict involved, even if it isn’t based on facts.

The fact that the questioner was there to, in his words, demand accountability from officials – and who doesn’t want that? – leads viewers to sympathize and identify with that side of the conflict that’s been constructed.

While the reporter notes the source is an anonymous account, he doesn’t investigate who is behind it or directly fact-check it. He also notes that it was posted with genuine records, which gives the claims additional credibility.

8. Amplification by a trusted news outlet and influencers:

As is standard practice for the TV station, the news broadcast is clipped and segments are posted to its social media channels. The station’s posts are reshared by local activists and community leaders, further spreading the narrative.

Even a skilled investigator might struggle to uncover who is behind @CleanGovWarrior and fact-check the allegations. But by that point, the disinformation has already had its effect.