The question of whether generative artificial intelligence is convincing enough to affect our politics is outdated. Sophisticated voice cloning, virtually undetectable deep-fake videos and realistic fake images have spread in the United States and abroad. The better question is: How will these advancements in AI affect our relationship with the truth?

This election season, a robo-call that mimicked President Biden’s voice tried to discourage people from voting in the New Hampshire primary. Fake images of Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump’s mugshot spread immediately after his arrest. A doctored video of Biden attacking transgender people also made the rounds.

In one of the latest examples of generative AI supercharging disinformation, a manipulated video mimicking Vice President Harris used her voice to say Biden “exposed his senility” while parroting racist attacks on Harris’s campaign – a video the world’s wealthiest man, Elon Musk, shared on social media to almost 200 million followers.

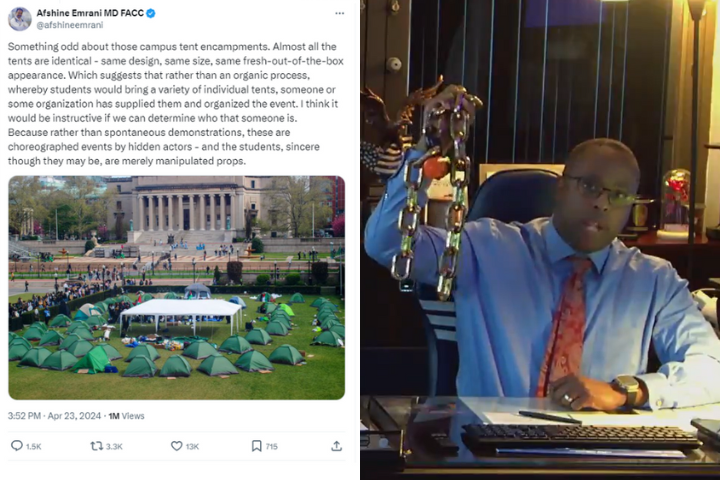

The use of disinformation to sway political outcomes or to sow societal division isn’t new, but cheap and easy-to-use technology that can distort reality is advancing rapidly as detection tools lag. Still, the main lesson learned in recent years is how technology itself isn’t the biggest threat.

While reporters immediately debunked the robo-call and most viewers would be skeptical of video depicting Harris degrading her own campaign, research shows generative AI is contributing to a growing sense that nothing we see is real. This phenomenon exacerbates an idea bad actors can weaponize: The truth is impossible to know. For reporters, the first step to empowering the public is to help people navigate this evolving information landscape, especially ahead of the presidential election.

“We’re not doing the public a service by telling them technology is scary,” said Dean Jackson, a democracy, media and technology researcher who served on the Jan. 6 select congressional committee with a focus on social media’s role in the insurrection. “Journalists need to help voters understand what they can do to protect themselves from what are essentially tech-facilitated political scams.”

Journalists need to help voters understand what they can do to protect themselves from what are essentially tech-facilitated political scams.

Dean Jackson, a democracy, media and technology researcher who served on the Jan. 6 select congressional committee

Turning off the tech blinders

The deep-fake Biden robo-call starts with a favorite phrase of his: “What a bunch of malarkey.” The call goes on to encourage voters not to cast ballots in the Democratic primary and falsely claims that voting in the primary would prevent residents from voting in the general election.

“Voting this Tuesday only enables the Republicans in their quest to elect Donald Trump again,” the call says. “Your vote makes a difference in November, not this Tuesday.”

The Democratic political consultant accused of creating the impersonation deep fake, using voice-cloning software from ElevenLabs, is facing a $6 million fine and multiple felony counts of voter suppression.

The robo-call is one of the most high-profile examples of AI being used to mislead voters in the United States while supercharging existing misinformation narratives. Exploitation surrounding fears over votes not being counted is a common voter suppression tactic.

The case also spurred lawmakers to advance regulation – particularly at the state level – and helped to inform coverage of deep fakes among journalists. It showed us that even when the technology is so advanced, focusing on the human aspect of a story – in this case, voter suppression and fear – can go a long way in shaping coverage.

“Tech is not always the best angle for a story,” Jackson said. “I prefer it when stories start with harms and work backward toward the role of technology, instead of explaining new tech and speculating about hypothetical harms. It helps to ground the analysis in reality and spotlight non-technological solutions.”

There’s no evidence the robo-call had a tangible effect at the polls, and it’s too soon to know whether AI will pose a threat to U.S. elections later this year. But elections abroad provide insight into the threats AI can pose to democracy.

In Slovakia, for example, an audio deepfake posted on Facebook before a close election falsely depicted a left-leaning candidate and a journalist planning to rig the election. The candidate quickly noted the audio was fake and journalists reported it was likely created using a voice-cloning software, but because the media and politicians must remain publicly silent 48 hours before polls open, the audio proved difficult to debunk. The candidate ended up losing.

Drawing a straight line between a single piece of misinformation and an electoral outcome is difficult, but the Slovakia example shows the difficult job journalists have in debunking generative AI. Voice cloning, in particular, is difficult to detect because it lacks the visual inconsistencies common in video deepfakes or the syntax errors in AI-generated text. Detection tools are unreliable in determining whether a video or audio clip was AI-generated.

The rise of deep fakes is also eroding public trust.

An August 2023 YouGov survey showed 85 percent of respondents were “very concerned” or “somewhat concerned” about the spread of misleading video and audio deep fakes. Heightened awareness of misleading AI not only poses concerns for journalists trying to rebuild trust, but also allows politicians and public figures to falsely claim real content is fake – a phenomenon called the “liar’s dividend.” The “liar’s dividend” takes another option off the table for journalists hoping to confirm the authenticity of a video or audio clip: the clip’s subject. It’s too easy for public figures to wield the concept of generative AI as a weapon to suit their needs.

“The liar’s dividend thing seems new – not categorically new. Politicians have denied evidence of wrongdoing before, like Trump with the [Access Hollywood] tapes – but maybe quantitatively new,” Jackson said. ”Denial could be easier, more plausible and more common.”

He added: “The way journalists talk about this issue is very important. And I’ve heard a lot of good tips from journalists about how to report on these issues so they inform the public rather than leaving citizens feeling disempowered by technology, and so they can help add context to accusations even when claims about evidence are conflicting.”

What works in the age of AI

How do journalists tackle generative AI and the problems it can create?

Janet Coats, managing director of the University of Florida’s Consortium on Trust in Media and Technology, stressed the importance of classic reporting tactics when covering the authenticity of a clip or exposing a deep fake – specifically, placing AI-generated disinformation in historical context.

“Does this feel like something this person would say or do?” she said. “Does this contradict a narrative that we know to be valid and fact-based? I think a lot of it is applying the same kind of reporting skills that we have in questioning authority, really prosecuting information we’re getting.”

Taiwan may hold some answers on how to successfully cover an election shaped by disinformation.

In Taiwan’s 2024 presidential election, AI-generated disinformation targeted politicians and their private lives, according to a report from the Thomson Foundation, an international media development organization.

Taiwanese public media used fact-checking and “prebunking” – the preemptive debunking of false information before it spreads – and placed a focus on earning the public’s trust and boosting media literacy. Despite false voter fraud claims, alarmist warnings of war and the amplification of Chinese military propaganda, Lai Ching-te of the Democratic Progressive Party, who is opposed by China’s government, was elected.

“The example from Taiwan is a great demonstration of the power of trusted messengers in responding to AI-generated disinformation threats,” Jiore Craig, a fellow at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, said in a webinar organized by the Thomson Foundation. “Media or any messenger that earns its audience’s trust has the opportunity to make impactful choices when a disinformation attack presents.”

Coats said journalists in the U.S. need to think outside the box to build that kind of trust with audiences. If bad actors are using repetition and the co-opting of trusted messengers to spread false information, journalists should try those same techniques to disseminate the truth.

The example from Taiwan is a great demonstration of the power of trusted messengers in responding to AI-generated disinformation threats.

Jiore Craig, a fellow at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue

“There’s a lot to learn from the people who have very successfully spread this kind of bad information. … The techniques they use work,” she said. “We have to go to school on those techniques, too. You have to fight fire with fire, use the same kinds of mass distribution techniques … instead of just relying on the fact that we wrote stories, or we did a video.”

That’s not to say all of the techniques disinformers use should be co-opted.

Coats noted the importance of using careful language, avoiding words that incite strong emotion, which could cue to readers that something is amiss.

“I think that in terms of trust-building, using language that is more neutral, that feels less judgy to people, that’s a piece of trust-building,” Coats said. “And that’s something we control – we control the way we describe things.”

She said she recognizes that’s not rewarding in the short-term, but in a media environment where so much feels out of control, Coats said journalists need to focus on steps they can take to make a difference, no matter how small.

Generative AI is only going to become more savvy, easy to use and affordable. It will allow disinformers to “flood the zone” with false information that looks more and more real. But if journalists want their audiences to remain empowered, hopeful and well-informed, they need to provide them with tools to do so. Reporters and editors can take a page from Taiwan’s playbook: Move away from alarmist conversations around technology, and talk to audiences about media literacy, trust and transparency.

Tech won’t save us from tech – it’s on human beings to do that.

This story was originally published by Investigative Reporters & Editors in a special 2024 elections issue of The IRE Journal.