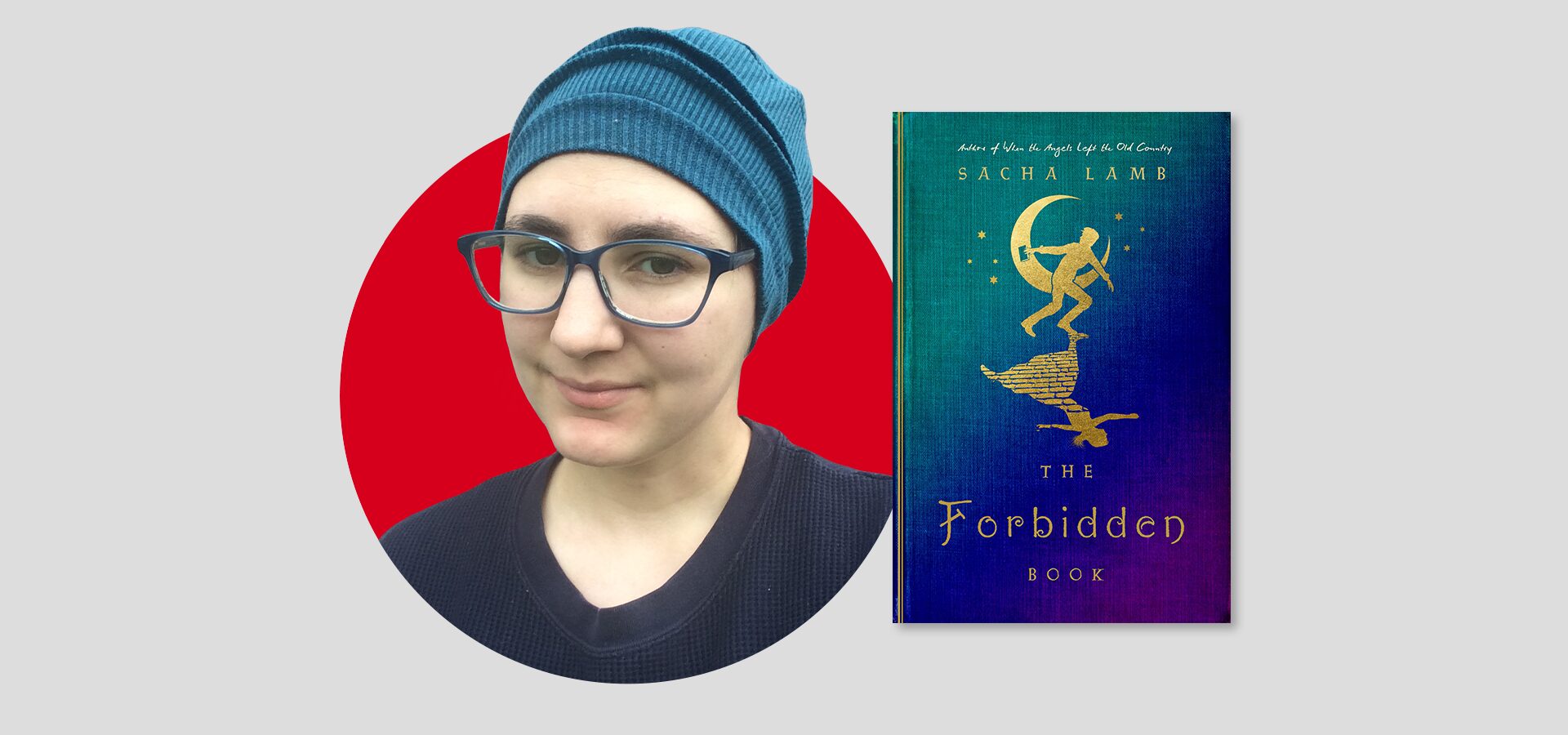

Drawing upon elements of Jewish folklore, Sacha Lamb’s latest young adult novel The Forbidden Book (Levine Querido, 2024) is a genderqueer dybbuk story of spiritual possession set in an 1870s shtetl in Eastern Europe. Protagonist Sorel runs away from her life on her wedding night and takes on the male identity of Isser Jacobs to prevent people from finding her. However, Isser Jacobs has a reputation for printing illegal political pamphlets–bringing Sorel on an adventure through the dark underworld of her small Jewish city that uncovers wicked angels and others fighting for control.

In conversation with Communications Intern Julia Goldberg for this week’s PEN Ten, Lamb outlines the gendered aspects of spiritual possession, their writing process, and how Yiddish literature inspired Sorel’s story. (Bookshop; Barnes & Noble)

What inspired you to write The Forbidden Book? When did you start writing it and how long did it take you to finish it?

The initial idea was the opening scene of a young girl possessed by a dybbuk, a spirit, who helps her escape her wedding. That scene came to me while I was still working on When the Angels Left The Old Country. I knew that I wanted to write a trans/genderqueer dybbuk story, and it seemed like a good fit for my second novel, but I didn’t start drafting until 2023. I usually do a lot of thinking and research before I start to write, and then I write my draft from start to finish in a relatively short time. This one took me six months or so from when I actually started to put words in order, to finishing the draft. It ended up being complete enough that we didn’t have to do extensive edits, and it was off to the presses within a year of writing the first chapter.

The Forbidden Book draws upon elements of Jewish folklore, stories, riddles, and other literary and oral traditions that date back hundreds of years. When did you first encounter Jewish folklore, and how did you choose which elements to bring into The Forbidden Book?

Folklore and fairytales and classic fantasy have been interests of mine forever, since my parents played audiobooks of The Odyssey and Tolkien and Le Guin around the house before I was even old enough to read them myself. But Jewish folklore specifically I didn’t get into until I was in my 20s, thanks to some friends who pointed me to Howard Schwartz’s fairytale collections from around the Jewish world. I got really into Yiddish literature while I was working on my master’s in history and learning Yiddish to help read immigration documents. For this story obviously I drew inspiration from the most famous dybbuk story of all time, S. An-sky’s play The Dybbuk. I also brought in some stories about Angels of Death. The character of Agrat bat Machlat, a female angel of death, is partly invented. She is a female angel or demon folklorically, but I made her aesthetically a fairy queen and gave her some details and powers that aren’t from folklore, to fit the needs of the plot.

The rest of the folklore is mostly women’s practices relating to cemeteries and the dead. The Jewish cemetery was an interesting place in shtetl life because it was both forbidden for some people to enter, dangerous due to the presence of the ritual impurity of death, but at the same time it’s a place where you often see old women and beggars spending time or even living, a relatively secure spot to sleep if you’re lost and destitute. So I was really thinking about the space of the cemetery and the living and non living entities who pass through it and dwell within it, and for the book I pulled together different threads of folklore relating to that space.

In Jewish folklore, the dybbuk is a lost spirit that travels into the body of a living person. What inspired you to use the concept of the dybbuk as a means of exploring questions of gender expression and identity?

The gendered aspects of dybbuk possession aren’t my invention; they’re actually quite prominent in rabbinic and folkloric sources. Many, maybe the majority of accounts of dybbuk possession are of young women possessed by male spirits. Sometimes those spirits were Torah scholars in life, and speaking in the voice of the male spirit, the possessed young woman can claim a kind of authority she doesn’t have as herself. In An-sky’s famous play, the bride Leah is possessed by her deceased fiance Chonen, creating a kind of dual-gendered entity, and Chonen’s conflict is rooted in the fact that his father and Leah’s had vowed to marry their children to each other–which you could read, queerly, as a deferred vow of marriage between the fathers themselves. But Leah’s father breaks that vow, which lets the dybbuk possess her.

An-sky was drawing on folklore that he’d studied as an ethnographer in the 1900s, and I’m drawing both on An-sky and on that same folklore. In the case of Sorel and Isser, we have a girl who is already uncomfortable with her position but doesn’t feel equipped to escape it, and being possessed by the spirit of this boy who is sort of her twin, an orphan that her father has taken under his wing, opens her up to becoming a different person, a person that she likes better. “Sorel” and “Israel,” Isser’s full name, are almost anagrams in Yiddish letters, and Isser was kind of living the life that Sorel wants to have. But he lost that life, and it’s up to Sorel to figure out why and how. She’s possessed, but in a way she’s the one taking over his identity as she wakes up to the possibility of a genderqueer/butch existence.

I was really thinking about the space of the cemetery and the living and non living entities who pass through it and dwell within it, and for the book I pulled together different threads of folklore relating to that space.

The Forbidden Book and your debut novel, When the Angels Left the Old Country, lie at a similar intersection of genres; both are works of queer, Jewish, historical fantasy. How did exploring this intersection in your first novel inform your approach to writing this novel?

Although I wrote Angels to entertain myself, at the same time it’s making kind of an ambitious statement: that a world steeped in traditional Jewish folklore and philosophy can also be a totally queer world. The fact that it was the first book to win both Sydney Taylor and Stonewall medals in the same year shows that people responded really well to that message. Now that I’ve made my grand statement of worldview with Angels, I want to explore different angles of it, how queerness can manifest in different contexts and different moments of Jewish history, and how even what we think of as “traditional” Jewish society is multidimensional no matter the time and place.

Are there specific time periods or regions from which you drew inspiration for the political tensions within The Forbidden Book? Did you conduct any research, historical or otherwise, as you wrote the book?

The book is set in the 1870s, which is about a decade before Jews began to emigrate in large numbers from the Russian Empire. Essentially, earlier in the 19th century the shtetl was a center of commerce, and at the end of the 19th century, antisemitic legislation and economic depression led millions of Jews to leave the Pale of Settlement and migrate to the Americas, Western Europe, and Ottoman Palestine. But the in-between period of the 1870s was a time when things were sort of unsettled and undecided. Some Jews were becoming more interested in secular literature and politics, while others were becoming more conservative religiously. More women were getting educated, which caused anxiety for the traditional patriarchs. But the infamous pogroms of the 1880s hadn’t yet happened, so for a lot of Jews the most proximate political questions were about their relations with other Jews.

The shtetl in the book, Esrog, is made up, but it’s partly based on Berdichev, which was a center of the Jewish printing industry, and partly on Ostroh (the name Esrog is a pun on the Yiddish for Ostroh, “Ostrog”), a town in Ukraine which stagnated economically after the railroad lines skipped past it. Esrog is a town that used to be a commercial center because it’s on a river, but the new railroad makes it economically irrelevant, its future uncertain.

In this context I created essentially a completely Jewish world. There are a handful of gentile characters, but the agency in the book is all Jewish agency. And it’s a conflict between older Jews who have their visions for what the Jewish community should look like, and younger Jews who have a different vision. All communities go through this, but for marginalized communities the stakes are high because we worry that the vulnerability of going through a change will open us up to harm from outside our community. Although the context is so Jewish, it’s also universal. This is the story of fathers and their children in conflict, exploring the fear of change, and the fact that change is necessary.

You intersperse Hebrew and Yiddish terms throughout The Forbidden Book, though you rarely define them explicitly. What effect were you hoping that choice would have on your readers — and more broadly, were you writing with a specific readership in mind?

I used fewer Hebrew and Yiddish words in this book than my first one, ironically because I thought of it as a book that “takes place” in Yiddish, whereas Angels I imagined as “taking place” in a Yiddishized English. Still, it’s difficult to imagine a Yiddish world completely translated, and I find it alienating as a reader when the author has to pause to explain cultural details to me, so I prefer to sort of “hide” the explanation using context clues. It’s subtle, but I also used more Yiddish phrases for the POV of Isser than for Sorel. Sorel is from a higher social class, and would be educated in Russian, so her narration uses fewer traditionally Yiddish idioms.

While obviously I do expect these familiar details to appeal to Jewish readers, I also hope that readers who aren’t as familiar with the world of Eastern European Jews can relate to the universal story of young people making their own choices. I’ve had really positive responses to the vocabulary of Angels, so I do trust readers to come along for the ride, even if they don’t know anything about Judaism!

It’s a conflict between older Jews who have their visions for what the Jewish community should look like, and younger Jews who have a different vision. All communities go through this, but for marginalized communities the stakes are high because we worry that the vulnerability of going through a change will open us up to harm from outside our community. Although the context is so Jewish, it’s also universal.

Which scenes or characters proved the hardest to write? What strategies did you employ when working through especially difficult aspects of your novel?

I mentioned before that I write my drafts from start to finish. For The Forbidden Book that’s only halfway true. The novel has two points of view, Sorel and Isser, in two timelines. I actually wrote Sorel’s POV for the first two acts, then realized I needed Isser’s as well, so I went back and wrote his POV for those two acts, interpolated them, and from there moved on to act three. In between that I literally made a red-thread conspiracy-board type map of the clues I’d set out for Isser’s murder (I used red ink instead of thread, so I could carry it around in my notebook, but it’s got all the suspects, all the motives, means, and opportunities). So it was really about keeping track of every thread of the plot and the motivations of all these different players.

In your acknowledgements, you thank those who have fought against censorship and advocated for teenagers’ right to read. To what extent did the current landscape of literary censorship influence your decision to center it as a theme in your novel by including the illegal printing of political pamphlets in Isser Jacobs’ narrative?

Weirdly this wasn’t something I consciously set out to write about, but I think anyone in the world of children’s literature in the [United] States right now can’t escape it. It happens that censorship is a huge theme of Jewish history, going back to the Middle Ages, so it was sort of a natural fit. In An-sky’s Dybbuk, the boy who becomes the wandering spirit is studying Kabbalah, a transgressive act for a young unmarried person—traditionally it’s thought to be dangerous for someone without the worldly ties of a mature individual to study the secrets of Kabbalah. My character Isser is studying a different kind of transgressive text, the social criticism in Yiddish that started to come out in the 1870s and also socialist works coming from Western European revolutionaries like Marx. These works and anything that allowed Jews access to political thought were targets for Russian censors.

I’m not happy to say so, but this does feel like something teens today can relate to. Letting young people have access to full, diverse, and accurate information about the world scares those who feel insecure in their own position of power. But it’s a lot harder to maintain a regime of censorship than those people want you to think, and pushing back can get you real results, so don’t give up.

What advice would you give to your younger self or other young, queer writers?

The biggest psychic obstacle I’ve had to overcome is the thought that my own queer experiences might not be legible enough to others. My advice is don’t self-censor and don’t self-reject. Others will question you enough, so don’t be your own first uncharitable critic.

Letting young people have access to full, diverse, and accurate information about the world scares those who feel insecure in their own position of power. But it’s a lot harder to maintain a regime of censorship than those people want you to think, and pushing back can get you real results, so don’t give up.

What’s the last great book you’ve read? What are you planning to read next?

In kidlit, I’ve just been reading Spells to Forget Us by local Boston author Aislinn Brophy. I love how they explore the expectations that are laid on teen girls, Black girls in particular, and how each of their protagonists deals with those pressures in a different way. And Spells to Forget Us is also a really cute romance packed with fun Boston details!

Outside of kidlit I’m also reading M.M. Olivas’s California desert gothic debut Sundown In San Ojuela (out November 19th). It’s so spooky and brutal.

My TBR is probably as tall as I am, but two new releases this fall I’m stoked for are Ariel Kaplan’s The Republic Of Salt (the second in a fantasy series set in Jewish Spain), and Emi Watanabe Cohen’s middle-grade Golemcrafters. I really liked Emi’s debut The Lost Ryū and I think she really hasn’t gotten the attention she deserves, so I hope everyone gives Golemcrafters a try.

Sacha Lamb is a 2018 Lambda Literary Fellow in young adult fiction, and graduated in Library and Information Science and History from Simmons University. Sacha lives in New England with a miniature dachshund mix named Anzu Bean. Their debut novel, When The Angels Left The Old Country, was named a Printz Honor Book, a Sydney Taylor Award winner and a Stonewall Book Award winner Their latest novel is The Forbidden Book.