Impact Report

Evaluating PEN America’s Media Literacy Program

PEN America & Stanford Social Media Lab

Preview

The goal of PEN America’s media literacy work has always been to better equip those we reach with the skills and knowledge to assess the credibility of information and to make informed decisions about what news sources to trust. Since launching our Knowing the News media literacy program in 2020, we have been eager to conduct an evaluation to assess the impact of our workshops. As noted in the paper below, there is also a dearth of research to assess the effectiveness of interventions that attempt to counter the effect of disinformation specifically in communities of color, even though those communities are disproportionately targeted. In order to address these knowledge gaps, PEN America partnered with the Stanford Social Media Lab to conduct an evaluation of the effectiveness of the workshops we offered for Asian American and Pacific Islander, Latino, Black, and Native American communities in 2021.

In this report you will find:

- A description of the history and methodology of PEN America’s media literacy programming.

- A summary of PEN America’s qualitative findings from the listening sessions and workshops we conducted in 2021 and a summary of the key findings from the Stanford Social Media Lab’s evaluation of those workshops.

- A white paper drafted by the Stanford Social Media Lab, laying out in more detail their evaluation findings.

PEN America has published the Stanford Social Media Lab paper in order to provide for greater transparency into this program, its successes, and the opportunities for learning and adaptation. For those interested in the effectiveness of media literacy trainings, the link between mis- and disinformation and public health, and/or dynamics of misinformation and media ecosystems in communities of color, we hope the results of this study will be instructive.

What is PEN America’s Media Literacy Program?

In 2017, PEN America published Faking News: Fraudulent News and the Fight for Truth, a landmark report on disinformation–which at the time we referred to as “fraudulent news”–and the threat it poses to free expression and open, democratic discourse. In the report, we noted that:

If left unchecked, the continued spread of fraudulent news and the erosion of public trust in the news media pose a significant and multidimensional risk to American civic discourse and democracy… even those implications that now seem farfetched should not be excluded from consideration. Such challenges include: the increasing apathy of a poorly informed citizenry; unending political polarization and gridlock; the undermining of the news media as a force for government accountability; … an inability to devise and implement fact and evidence-driven policies; the vulnerability of public discourse to manipulation by private and foreign interests; an increased risk of panic and irrational behavior among citizens and leaders; and government overreach, unfettered by a discredited news media and detached citizenry.

Today few of these risks seem farfetched, and the threat posed by dis- and misinformation to civic discourse and democratic society are clear. But as we warned in 2017, there is also a risk that the dangers of disinformation could be used to justify “broad new government or corporate restrictions on speech.” As a result, PEN America has always emphasized that a central component of responding to disinformation must be ensuring the public is empowered and equipped with the tools and knowledge necessary to make informed decisions about the credibility of information. We therefore also hold that media and news literacy programming must be central components of building public resilience against disinformation.

Over the past several years, such media literacy programs have been a core component of our work to stem the deleterious impact of disinformation on our democracy. Since 2020, we have carried out a program of work entitled Knowing the News to foster informed news consumption and empower individuals and communities with the tools and knowledge to assess the credibility of information and seek out reliable information. In the run-up to the 2020 election, we launched the What to Expect When You’re Electing disinformation defense campaign, to raise awareness of the threat posed by election-related disinformation and to gird the public and the news media against the concomitant threats to the credibility of the electoral process and the stability of our democracy.

In 2020, we continued to call out the dangers of anti-democratic disinformation campaigns, but we also pivoted to respond to the new dangers posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, which made starkly clear the life-or-death consequences of mis- and disinformation in the context of a public health crisis. And like the pandemic itself, the impact was disproportionately falling on communities of color, in part exploiting the fact that communities who have historically been underserved or mistreated by medical institutions exhibit low levels of trust in them, which can also lead to skepticism about public health campaigns. A year later, as COVID-19 vaccines were introduced and the nature of the pandemic and its impact continued to shift, many communities struggled with knowing what information to trust, and were also disproportionately targeted with mis- and disinformation. In response, in 2021, PEN America launched the Community Partnership Program to stem the impact of COVID-19- and vaccine-related mis- and disinformation in communities of color across the U.S.

For our work combatting vaccine misinformation, PEN America partnered with four organizations that are deeply invested in the health and empowerment of their respective communities: Mi Familia Vota (serving Latino communities), National Action Network (serving African-American communities); Asian Americans Advancing Justice – AAJC (serving Asian American and Pacific Islander communities) and the National Congress of American Indians (serving Native American communities).

PEN America’s model focuses on offering skills and resources to trusted leaders within these communities, recognizing that these individuals serve as important sources of credible information and are well-positioned to identify and counter mis- and disinformation in real time. As a result, the core of our program involved train-the-trainer workshops in which PEN America staff and affiliated experts on disinformation offered trainings to over 50 community leaders on how to identify, respond to, and combat digital mis- and disinformation. We also provided four public disinformation defense workshops to the communities served by our four partner organizations, which also featured doctors and fact-checkers from and serving those communities.

In order to build trust and ensure our programming was tailored to the experiences and needs of each community, our workshops were each preceded by preparatory conversations with project partners and closed-door listening sessions with community leaders to identify concerns around the sources and spread of vaccine mis- and disinformation, impacts on community behavior, and which efforts to combat mis- and disinformation have historically been most effective. We then worked with participants to discuss who could most effectively serve as trusted messengers of accurate information, what successful strategies for disseminating accurate information would be, and how to make more credible vaccine information accessible. In all, PEN America engaged directly with 2,262 participants and viewers, through listening sessions, train-the-trainer sessions and four public workshops. Another 5,000 people viewed recordings and feeds.

Key Findings

Listening Sessions & Workshops

This program allowed us to tailor our work to reflect the range of experiences and needs both within and across communities. From those conversations and workshops, however, we also observed trends and consistent findings that we believe can help inform efforts to respond to and defend against disinformation:

- The communities we heard from reported experiencing a dearth of simple, consistent, messaging about vaccination presented in relevant languages. Our interlocutors spoke of the need to translate and make accessible credible information about the effectiveness and safety of the vaccines, and messaging to debunk COVID-19 myths, but also reported that such efforts were lacking. They spoke of a dire need for more culturally competent and responsive public health messaging that engages with communities of color, including diaspora communities. And they emphasized the importance of trusted messengers like individual community and faith leaders, influencers, and community media as alternative information sources that can effectively shape community opinion and call out disinformation.

- Historical and ongoing inequities in media coverage of and for communities of color have led to a crisis of trust in mainstream media within these communities–an issue that was compounding the crisis of health-related mis- and disinformation. As a result, communities often turn to messengers and newsrooms they trust, such as community and ethnic media outlets that provide in-language information and reflect the community’s perspectives and values. Unfortunately, these outlets are often poorly funded, under-resourced, and frequently unable to access sufficient fact-checking support. In other words, the most trusted sources are also the least equipped to respond quickly or comprehensively to counter disinformation, especially in a moment of crisis. Some communities are offered very few options with in-language accessibility; for example, interlocutors spoke of Chinese diaspora communities having to choose between The Epoch Times (an outlet that The New York Times described in 2020 as “a leading purveyor of right-wing misinformation”) and outlets that publish Chinese Communist Party propaganda.

- The communities we heard from noted that a great deal of the flow of mis- and disinformation within diaspora communities in particular occurs not on major platforms like Twitter or Facebook, but largely through private, less-studied messaging apps like WhatsApp and WeChat. As a result, information received from abroad can reach and exit the U.S. without ever undergoing fact-checks or translation—and without those studying and tracking disinformation in the U.S. gaining an understanding of its impact.

- The impact of historical traumas and associated distrust in institutions–including medical institutions–that give people good reason to be wary of official or mainstream information sources must be taken into account in order to understand the way mis- and disinformation works in communities of color. Participants mentioned in particular the experience of those older members of the Chinese diaspora who had lived through the Chinese Cultural Revolution, the long-term legacy of violence against and betrayals of Native American communities, and the impact of the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis among Black communities, among other examples.

Collectively, these findings highlight the importance of trust-building within communities of color, working with and through community and faith leaders, and supporting community and ethnic media in bolstering disinformation resilience.

Stanford Social Media Lab Evaluation

Researchers at the Stanford Social Media Lab designed and deployed a two-part evaluation survey. Participants in PEN America’s community-wide trainings were asked to indicate their familiarity with media literacy skills and to judge the truthfulness of a set of news headlines. Participants completed Part I before their media literacy training, and Part II afterward.

Stanford’s Social Media Lab found that the workshop successfully improved participants’ digital media literacy skills, their willingness to research the veracity of headlines, and their accuracy in discerning between true and false news.

Key findings include:

- Overall, participants in the community-based interventions significantly improved their digital media literacy skills. There were significant improvements in participants’ lateral reading skills, use of reverse image search, click restraint, use of fact checks, and monitoring of emotional reactions to headlines.

- The intervention also significantly improved participants’ ability to distinguish between true and false news. Participants’ likelihood of correctly evaluating the veracity of a headline rose from 47% to 61%.

- Participants showed particularly strong improvement in their ability to detect COVID-19 misinformation, from a pre-intervention average of 53% to a post-intervention average of 82%.

- Participants were also more likely to investigate headlines by applying their digital media literacy skills after the intervention. Participants’ investigation of a news headline increased from 6% to 32% after participating in a community-based workshop.

The Stanford Social Media Lab conducted this evaluation with participants in PEN America’s community workshops, presented live over Zoom, and then repeated the evaluation with a randomly selected audience who viewed the workshops via video. They found the impact to be more significant among those who participated in the community workshops, suggesting that those seeking out media literacy skills are also more likely to adopt them, but also that reaching the public via trusted community organizations is an effective means of maximizing the impact of media and news literacy trainings.

Impact of Community-Based Digital Literacy Interventions on Disinformation Resilience

An impact report by Stanford Social Media Lab

Introduction

Disinformation threatens our society by undermining people’s trust in institutions, organizations, and one another. The costs of inaction are both obvious and disturbing. Without concerted efforts to educate our citizenry, society will continue to be beset by disinformation and eroded trust. As the Aspen Institute’s 2021 Commission on Information Disorder report lays out, a key response required to overcome the misinformation crisis is civic empowerment. As the report notes, digital media literacy interventions are “an essential complement to other supply-side strategies that platforms must undertake (e.g., promoting factual content, reducing the reach of content that violates platform policies on disinformation, and prioritizing design that promotes healthy product usage). Users need to understand how information reaches them and have the tools that can help them distinguish fact from falsehood, honesty from manipulation, and the trustworthy from the fringe” (p.66).

The costs of inaction also include exacerbated inequality in communities of color, which are disproportionately targeted by disinformation campaigns and often do not have access to the same structural resources needed to counter them (Gu & Hong, 2019, Freelon et al. 2020, Gallon, 2020, Nguyen & Catalan, 2020, Soto-Vasquez et al., 2020, Longoria, 2021, Nguyen et al., 2022). Analysis of the Internet Research Agency’s attack on the 2016 American presidential election revealed that their disinformation campaign on social media chiefly targeted Black voters by spreading fraudulent information about political candidates and election outcomes (Gallon, 2020). Indeed, Gallon estimates that millions of dollars were spent on digital ads deployed across the Internet to dissuade Black Americans from voting (2020). The Latino community has also been disproportionately impacted by malefactors, who exploit the dearth of Spanish-language opportunities for media literacy education and fact-checking outlets to spread misinformation (Soto-Vasquez et al., 2020; Nguyen & Catalan, 2020; Longoria, 2021). Most recently, the Latino community has been the target of extensive COVID-19 disinformation that endangers the lives of their community by discouraging vaccination and endorsing false cures (Soto-Vasquez et al., 2020; Nguyen & Catalan, 2020; Longoria, 2021).

Despite the fact that minority groups are disproportionately targeted by disinformation campaigns, most media literacy interventions have been developed for and tested with predominantly white, middle-class populations (Walther et al., 2014; Saltz et al., 2021; Yousuf et al., 2021). Growing research shows how different communities encounter, experience, and respond to misinformation in vastly different ways, and individuals must often navigate information deserts, language barriers, and the challenges of systemic under-resourcing that make it more difficult to verify information (Soto-Vasquez et al., 2020; Dodson et al., 2021; Nguyen et al., 2022). The field of misinformation research has not yet addressed this need. While culturally responsive and developmentally appropriate pedagogy shows that interventions can be tailored to the needs of specific populations, there is currently little research on how to tailor digital media literacy interventions to the specific strengths, needs, and values of at-risk diverse communities.

Through this project, PEN America sought to respond to this need by developing tailored digital media literacy interventions in collaboration with community leaders from organizations led by and serving Latinx, Asian American and Pacific Islander, Black / African American, and Native American communities. In this white paper, we report on key findings regarding how individuals from different backgrounds experience and respond to disinformation, and demonstrate the efficacy of our tailored interventions in bolstering their ability to discern between true and false news. We examined the impact of the intervention on a community-based sample recruited by PEN America’s nonprofit partners, as well as in a randomized control trial.

A Community-Based Approach to Disinformation Resilience

It is clear that different communities are impacted by disinformation and misinformation in different ways. PEN America co-developed the content of the media literacy workshops based on listening sessions from community members and leaders from (1) Mi Familia Vota, a leading civic engagement organization dedicated to engaging the Latino community, (2) the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), the oldest and largest American Indian and Alaska Native organization serving the interests of tribal governments and communities, (3) Asian Americans Advancing Justice | AAJC (AAAJ | AAJC), an organization dedicated to advocating for the civil and human rights of Asian Americans, (4) and the National Action Network (NAN), a leading civil rights organization that promotes a modern civil rights agenda in the spirit of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to promote justice for all.

These listening sessions were centered around understanding where community members received their news and information and the specific narratives and effects of misinformation they encountered within their respective regions and communities. PEN America’s media literacy team listened and took note of the specific concerns raised around the sources and spread of vaccine misinformation, noting the dominant narratives of misinformation encountered, challenges in combating misinformation, and community strengths and solutions. PEN America worked with participants to discuss who can most effectively serve as trusted messengers of accurate information, successful strategies for disseminating accurate information, and the state of accessibility to credible news.

- Sources of information and disinformation. Community members emphasized the need for digital media literacy and education initiatives to recognize the importance of ethnic broadcast media as prominent sources of information, particularly by providing information in native languages (e.g., Spanish, Chinese) and elevating issues of importance to communities. For instance, broadcast channels such as Univision and Telemundo were noted as being particularly influential in the Latinx community. Similarly, NCAI members said that tribal news sites (e.g., Indian Country Today) and tribal health services (e.g., Indian Health Services, Seneca Nation Health System) tended to be regarded as central sources of trusted information. Ethnic social media communities and channels were also noted as important to sharing information within close networks, like family and friend group-chats, and the community at large. For instance, social media channels like WeChat, WhatsApp, and KakaoChat were listed as being particularly important in the AAPI community, in part because of their support of Asian languages and their widespread use internationally. In addition, networks like Black Twitter were central to sharing information among the Black community. All four listening sessions also cited public health institutions (e.g., the CDC, the WHO) as important sources of news about issues such as COVID-19 for people of all ages (although issues regarding trust in official institutions were also noted–see below), in addition to the importance of radio and TV among older populations.Across all of the listening sessions, people highlighted social media as a dominant source of misinformation. Specifically, large platforms such as Facebook, TikTok, and Twitter were named as being particularly notorious for exposing individuals to false information about COVID-19 and political issues. However, participants also discussed the role of private messaging apps and group-chats as sources of misinformation and disinformation. For instance, community members from both Mi Familia Vota and AAAJ | AAJC described instances where people shared false information in their group-chats, which was rapidly forwarded to many other individuals before being ultimately fact-checked and debunked.

- Dominant misinformation narratives. False claims about the COVID-19 virus and vaccines were common across all listening sessions. Community members described hearing misinformation about how the COVID-19 vaccine worked (e.g., that the shot contained active COVID-19 particles and would infect you), its side-effects (e.g., that the shot would cause infertility or heart disease), and its development (e.g., that it was developed in a “rushed” manner and its current administration was “experimental”). In addition, Mi Familia Vota described the prevalence of misinformation about people’s ability to access the vaccine. For example, many individuals believed that insurance or governmental ID were required to obtain COVID-19 vaccines. Furthermore, the AAAJ | AAJC listening session discussed common misinformation narratives about home remedies for COVID-19 circulating in group-chats (e.g., drinking boiling water to cure COVID-19). While the majority of the listening sessions focused on false claims about COVID-19, the AAAJ | AAJC group also described a concerning rise in misinformation in the AAPI community about the causes and perpetrators of anti-Asian hate crimes in the United States.

- Challenges to addressing misinformation. Efforts to address misinformation in communities of color need to acknowledge and account for a number of challenges. First, they must be sensitive to historic and ongoing systemic disparities in access to resources that influence how people make decisions about their health and civic engagement. Many communities in the United States have experienced and continue to experience discrimination in relation to their ability to access healthcare resources, information, and basic needs. Historical injustices, such as the Tuskegee syphilis study, remain salient for many individuals, who may hold distrust against federal institutions or public health initiatives. Beyond addressing the prevalence of false information, local and public organizations must work to address health disparities in order to build trust. The pandemic illustrates how important these long-term trust-building investments are to enabling effective responses in moments of crisis.Furthermore, more work is needed to make quality, credible information accessible to all communities in multiple languages. Many current approaches to disinformation prevention encourage people to use fact-checking resources to investigate claims they encounter online. However, the Mi Familia Vota and AAAJ | AAJC listening sessions described how these resources are often only available in English, or only have a limited subset of headlines translated into other languages (e.g., Spanish). As a result, it is often difficult for multilingual individuals to access credible fact-checks because few translations are available, whereas fake news is often rapidly translated into multiple languages.

- Community solutions. In imagining community-based solutions to combating misinformation, all groups emphasized the importance of building trust within the community and building upon existing efforts to improve information access to individuals. One initiative that was seen as particularly valuable was connecting communities to experts who shared their identities and could answer questions about topical issues. For instance, the NCAI highlighted the value of connecting Tribal communities with healthcare officials, doctors, and Tribal leaders who could provide guidance on COVID-19 misinformation while understanding and validating their concerns. In a similar vein, NAN members described potential collaborations with Black churches and pastors; community centers and leaders; and trusted sources on social media to share credible information and debunk prominent false claims.Another valuable pathway to improving misinformation resilience within communities is to foster supportive and productive one-on-one conversations. Based on the experiences of their field team organizers, MFV members felt that providing activists, journalists, and community members with straightforward, consistent messaging and data to counter misinformation in individual conversations would be valuable to their work. In particular, multiple groups noted the need to meet people with empathy when discussing false claims. They felt that addressing specific misinformation narratives and empathizing with individuals’ concerns while sharing personal experiences and trustworthy information could help improve trust in health information. Overall, they noted a need for conversational resources that prepared individuals and communities to talk about false claims.

Intervention Development

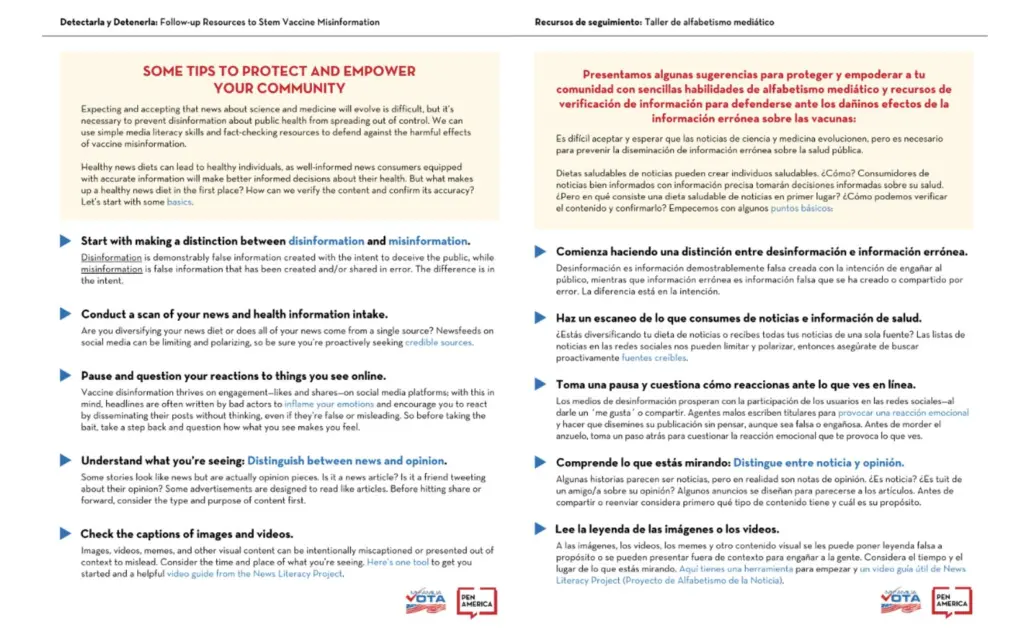

In response to information shared in the listening sessions, PEN America adapted its media literacy curriculum to create customized media literacy and misinformation defense workshops for community leaders, designed to train them to protect and empower their community from harmful, misleading narratives and other forms of compromised information.

PEN America’s co-designed workshops worked to ensure language access for our participants in the following ways. As shown below, native speakers translated all educational materials, including surveys, into Spanish. Live translations were also provided during all synchronous sessions by using the Zoom translation feature, where participants could opt to listen in English or Spanish. In addition, intervention materials acknowledged the need for multilingual fact-checking resources and shared links to specific organizations doing this work (e.g., Univision’s El Detector).

PEN America adapted the workshops to account for diverse media ecologies by highlighting a variety of sources of trusted information, including ethnic media organizations, and by discussing how to address misinformation across a variety of platforms. For instance, the resource packet designed for Native American communities included links to the Indian Country Today’s coverage of the COVID-19 crisis, as well as the NCAI’s list of COVID-19 resources for Indian Country.

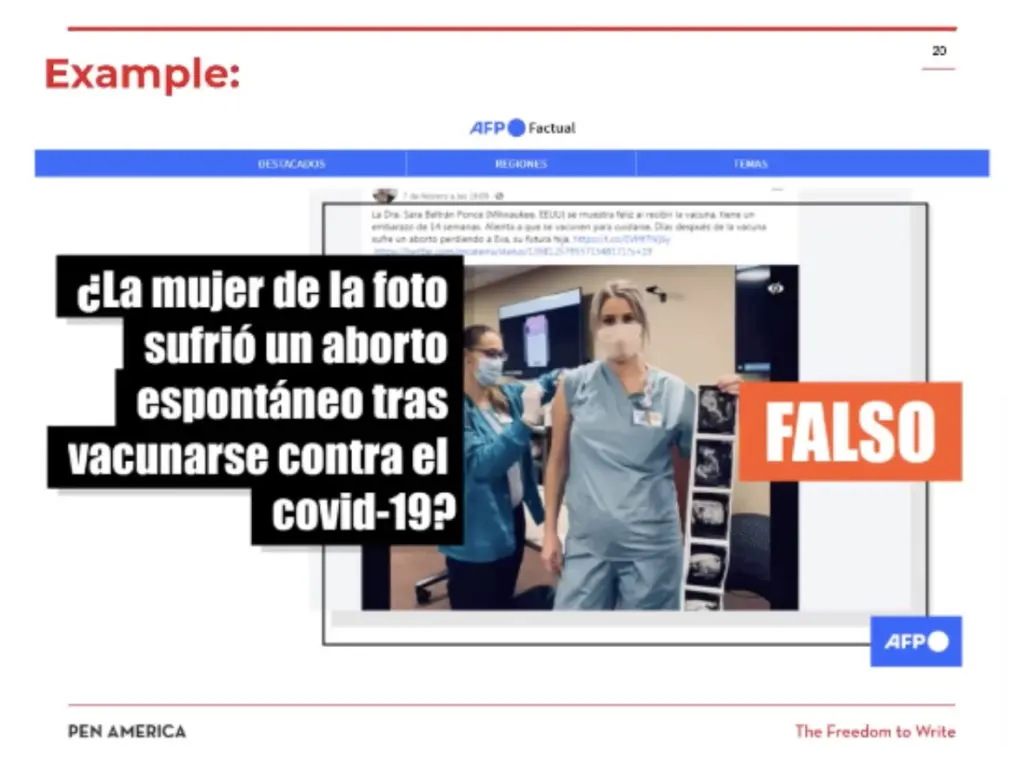

PEN America’s workshops specifically addressed sources of misinformation by explicitly calling out and ‘prebunking’ false claims (see Figure 1). In addition to building individuals’ awareness of these false claims, we also sought to build resilience against similar false narratives by explaining the ways in which disinformation campaigns target communities of color. As shown in Figure 3, we also included interactive components to our workshops by hosting an open Q&A session where participants could ask doctors who shared their identities about topics including COVID-19.

Community-Based Intervention

From October 14th to December 16th, 2021, 70 participants were recruited by PEN America and its community partners to complete one of four digital media literacy interventions tailored to the needs of specific communities. All workshops were approximately one hour and hosted on Zoom. The series of workshops were co-hosted by PEN America facilitators with a background in disinformation prevention, and representatives from each respective partner community organization. Participants were invited to take part in the pre-survey at the beginning of the workshop (N = 71) and to complete the post-survey at the end of the workshop (N = 59).

Our final sample of 45 participants was ethnically diverse. Approximately 18.4% identified as American Indians / Alaskan Natives, 12.2% as Hispanic / Latinx, 20.4% as Asian / Asian American, 6.1% as Black / African / African American, and 38.8% White.

To evaluate the efficacy of the interventions, the Stanford evaluators tested whether participants improved their (1) ability to discern between true and false news headlines, (2) willingness to investigate news headlines, and (3) comprehension of digital media literacy skills.

The evaluation found that the intervention significantly improved participants’ ability to discern between true and false news. Mixed effects logistic regression models were estimated to evaluate whether participation in the workshop (Time: 0 = before workshop, Time 1 = after workshop) changed participants’ ability to correctly evaluate headline veracity. Accuracy scores were calculated by coding headline evaluations as correct if individuals rated false news as mostly to definitely false (1-3 on a 7-point scale), and true news as mostly to definitely true (5-7 on a 7-point scale); responses of 4 were always coded as incorrect. Participants were modeled as random effects to account for dependency between each individuals’ headline judgements.

Results showed that participants’ ability to correctly identify true and false news increased significantly after the workshop (β = 0.56, SE = .21, p = .01). As shown in Figure 4, participants’ likelihood of correctly judging the veracity of headlines rose from 47% (95% CI = 38 – 56%) to 61% (95% CI = 52 – 69%) after the intervention. A closer examination revealed that individuals showed particularly strong improvement in their accurate judgment of true and false information related to COVID-19. A separate logistic regression examining only performance on COVID-related headlines showed that their ability to correctly identify true and false COVID-19 news increased substantially from pre to post-intervention (β = 1.39, SE = 0.35, p < .001), from a pre-intervention likelihood of 53% (95% CI = 41 – 64%) to a post-intervention average of 82% (95% CI = 71 – 89%).

People were also more likely to investigate the claims in headlines after the intervention. After completing all of the headline evaluation tasks, participants were asked to indicate whether they conducted additional research online to inform their judgment (e.g., using a fact-checker). To evaluate the impact of the intervention on this researching behavior, the evaluators estimated another mixed effects logistic regression model where the dependent variable (DV) was participants’ likelihood of conducting research on a given headline. The result was significant (β = 5.55, SE = .89, p < .001), with the rate of doing research increasing from 5.6% of the time before the workshop to 31.6% of the time afterwards. This suggests that one of the ways in which participants improved their ability to discern true from false headlines was by conducting more research on them before making a judgment about their veracity.

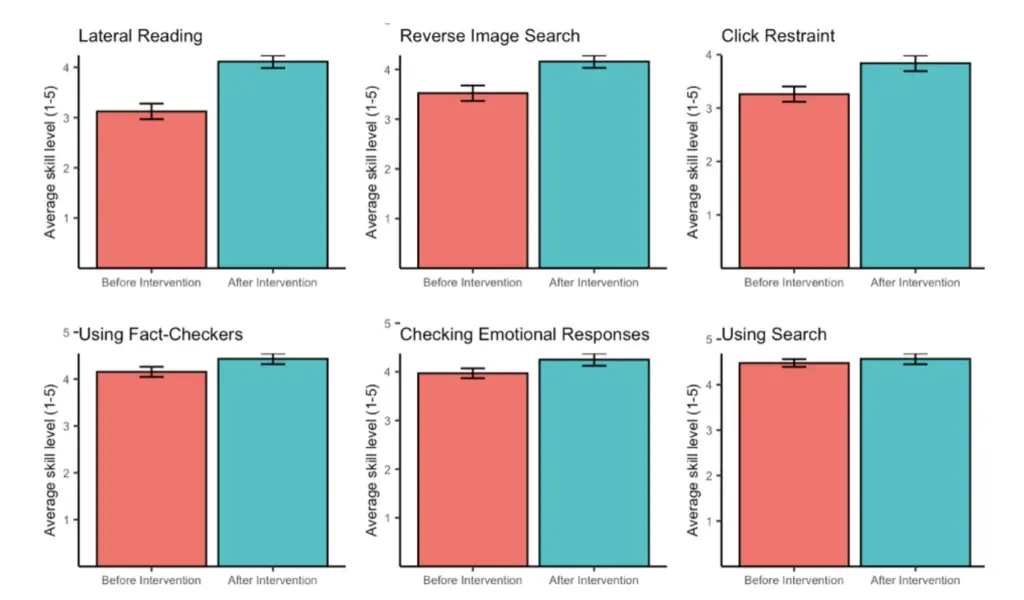

The intervention also improved participants’ digital media literacy skills. Overall, their average comprehension of digital media literacy skills increased from 3.12 (SE = .16) to 4.11 (SE = .13) (See Figure 4). Mixed effects linear regression models shows that the intervention led to significant improvements in participants’ lateral reading skills (β = .99, SE = .22, p < .001), use of reverse image search (β = .64, SE = .23, p < .001), click restraint (β = .58, SE = .21, p < .001), use of fact checks (β = .09, SE = .14, p = .027), and monitoring emotional reactions to headlines (β = .28, SE = .16, p = .029) (See Figure 2). Together, these results show that the intervention was effective in bolstering participants’ digital media literacy skills.

Randomized Control Trial Intervention

In addition to assessing the participants in PEN America’s community workshops, Stanford Social Media Lab’s researchers also conducted a randomized control trial of 300 participants recruited by survey organization YouGov between March 23 and April 12, 2022. The sample was composed entirely of participants who reported identifying as Hispanic or Latinx and was representative in gender (173 women, 127 men), age (average age: 45 years old, range: 19-81 years), and political affiliation (126 Democrats, 60 Republicans, 73 Independent, 41 Other / Not Sure).

Half of these 300 participants were randomly assigned to complete PEN America’s digital media literacy interventions tailored to the Latinx community. The interventions were 30 minute online videos, hosted by PEN America facilitators with backgrounds in media literacy. The other half of the participants were randomly assigned to participate in a control condition, in which they were exposed to a video about Zoom fatigue rather than the PEN America intervention. Participants in both conditions took pre-surveys prior to exposure to their condition’s content (either the PEN America intervention or the Zoom fatigue video) and post-surveys after exposure to the content. All 300 participants completed both the pre- and post-surveys.

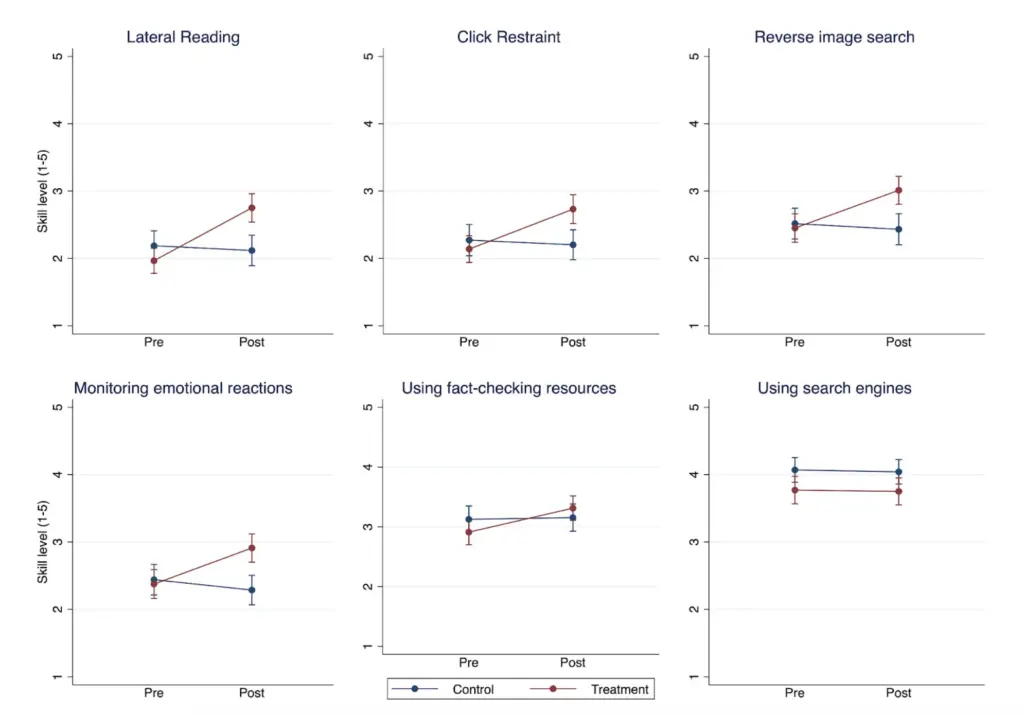

The intervention again significantly improved participants’ digital media literacy skills. Results from a series of mixed effects linear regression models showed that people who completed the intervention demonstrated significantly improved understanding of lateral reading (β = .85, SE = .12, p < .001), reverse image search (β = .64, SE = .10, p < .001), click restraint (β = .66, SE = .12, p < .001), using fact checking resources (β = .37, SE = .12, p < .01), and monitoring emotional reactions to headlines (β = .69, SE = .12, p < .001) relative to the control group (see Figure 5). These results show that the intervention was effective in bolstering participants’ digital media literacy skills across a variety of skills, at comparable levels to the community-based study.

However, the likelihood that people investigated the claims in headlines did not change after the intervention. For each headline they evaluated, participants were asked to indicate whether they conducted additional research online to inform their judgment of its veracity. To evaluate the impact of the intervention on this researching behavior, the evaluators estimated another logistic regression model where the DV was participants’ likelihood of conducting research on a given headline. Independent variables (IVs) were time, condition, and the interaction between the two. The interaction was not significant (β = -0.34, SE = -.28, p = .23). These findings suggest that the intervention improved participants’ knowledge of core digital media literacy skills, but did not make them more likely to apply those skills to headlines in this sample.

There are several reasons why participants may have been less likely to investigate the claims in the discernment task. One explanation may be that they were insufficiently motivated to fully engage with the task because they were recruited to participate in the study. Relative to the community-based sample where participants may be incentivized by a desire to protect their community, participants in the RCT may not feel as strong a need to employ their digital media literacy skills in their own lives. Alternately, participants may have also felt less motivated to investigate the claims because the RCT study was conducted in an individualized manner where participants were asked to watch the videos and complete the interventions on their own. In contrast, the community-based nature of the other study involved multiple people participating in workshops synchronously, which may have increased participants’ willingness to put their digital media literacy skills to use.

As a result, the intervention did not appear to improve participants’ ability to detect true and false news in a behavioral task, relative to the control group. We estimated another series of mixed effects logistic regression models to evaluate whether exposure to the intervention changed the likelihood that participants correctly evaluated the veracity of true and false headlines. The dependent variable was whether a veracity judgment was accurate (1 = accurate, 0 = inaccurate). Independent variables included time (1 = post-intervention, 0 = pre-intervention), condition (1 = treatment group, 0 = control group), and the interaction between the two, which was our key variable of interest. Participants were modeled as random effects. Overall, there was no significant interaction between time and condition (B = -0.05, SE = 0.11, p = .65), suggesting that the intervention did not improve people’s ability to discern between true vs. false headlines over the control. The interaction was also non-significant when analyzing true headlines (B = -0.09, SE = 0.17, p = .57) and false headlines (B = -0.01, SE = 0.17, p = .97) separately.

Closer examination of the intervention group’s performance on the discernment task indicated that participants selectively improved their ability to detect false news. They were more likely to correctly identify false news as false after the intervention than before the intervention (B = 0.56, SE = 0.12, p < .001). However, they were also more likely to incorrectly perceive true news as false after the intervention than before (B = -0.59, SE = .12, p < .001). Together, these results indicate that the intervention increased the salience of misinformation, affecting their judgments of not only false news but also true news.

Overall, these results indicate that online, scalable interventions administered through panel services to members of marginalized communities can be successful in improving their knowledge of approaches to addressing misinformation, but require strategies to support participants in applying the strategies in their daily lives and build discriminant trust in true and false news.

Comparing Intervention Effects Between the Community-Recruited and Panel-Recruited Samples

It may be possible that the intervention could have different effects for those who were recruited for the intervention organically through community members and organizations compared to those who were recruited by a survey company. Stanford researchers compared the community-recruited sample’s (1) likelihood of doing research on headlines to inform veracity judgments and (2) accuracy of those veracity judgments to the individuals in the randomized control trial who were assigned to complete the intervention.

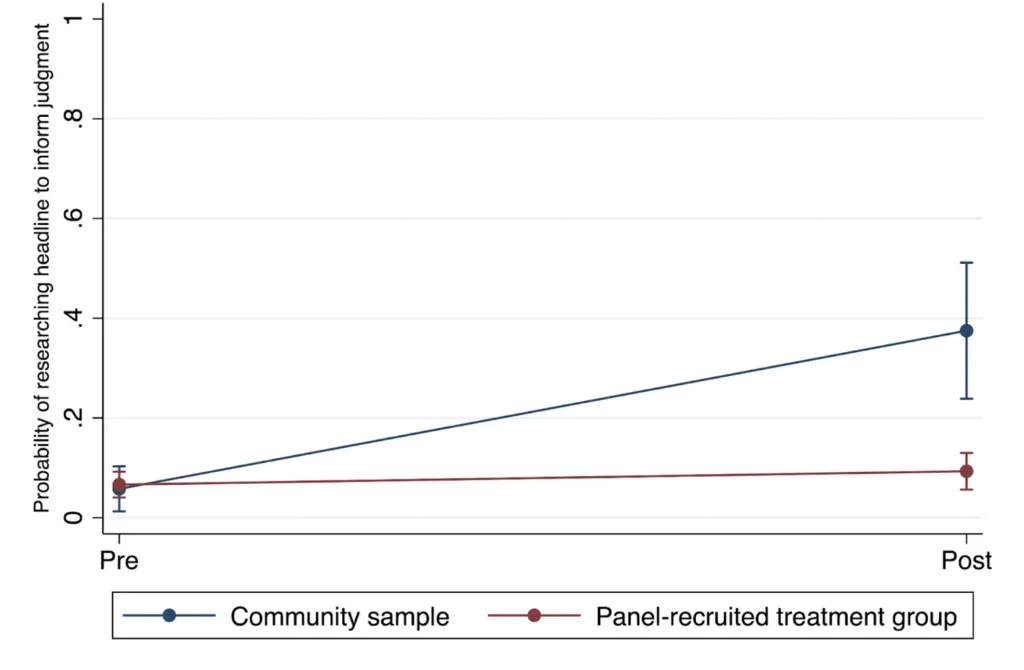

The researchers first estimated a logistic regression in which the DV was whether (1) or not (0) an individual reported doing research on a headline to inform their judgment of its veracity. IVs were sample (0 = community-recruited sample, 1 = YouGov panel-recruited sample), time (0 = pre-intervention, 1 = post-intervention), and their interaction. The results reveal that the community-recruited sample became significantly more likely to do research on headlines after the intervention relative to before compared to the panel-recruited sample (β = -1.91, SE = 0.51, p < .001). Both samples were not very likely to report doing research on headlines before the intervention, but after the intervention the community-recruited sample reported doing research 37.5% of the time while the panel-recruited sample reported doing research only 9.3% of the time (see Figure 6).

Researching Headlines to Inform Veracity Judgements

Finally, the researchers examined whether changes in the likelihood of accurately discerning true from false news before and after the intervention differed between the community and YouGov-recruited samples. To do this, the researchers estimated logistic regressions in which the DV was whether a headline judgment was accurate (1) or inaccurate (0). IVs were sample, time, and their interaction. The results reveal that while the two samples significantly differed in their pre-post change in the likelihood of accurately identifying true and false headlines (B = -0.54, SE = 0.23, p = .02), such that the community sample was more likely to accurately judge headlines after the intervention compared to the YouGov sample. Furthermore, while the intervention did not significantly improve either group’s likelihood of accurately judging false headlines (B = -0.06, SE = 0.36, p = .87), the community-recruited sample had a significantly lower propensity to inaccurately judge true news as false after the intervention compared to the YouGov sample (B = -1.00, SE = 0.33, p < .01) (see Figure 7).

Significance

Disinformation is a collective problem that requires a collective, but not monolithic, solution that uplifts all communities. Our results show that the PEN America digital media literacy workshops can improve the lives of individuals most targeted and impacted by disinformation through real-world interventions developed with and for communities of color.

Using qualitative focus groups from four non-profit organizations, PEN America worked with community leaders to identify common misinformation narratives, sources of exposure, and effective intervention strategies in the Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI), LatinX, Native American, and African American communities respectively. The listening sessions and additional consultations made clear that efforts to address misinformation should account for language diversity within and across communities, the nuances of ethnic media ecologies, and the role of historical injustices against communities of color in the United States in perpetuating distrust of modern institutions. Interventions should focus on translating educational resources into multiple languages, collaborating with trusted messengers and community and ethnic media outlets to promote trustworthy information and debunk false information, and centering the concerns of historically marginalized groups. Practitioners, academics, and public policy officials alike seeking to better address the misinformation crisis within communities of color should invest in adapting materials to multiple languages, media platforms, and messaging approaches (See PEN America’s work to empower communities to defend against disinformation).

The evaluation found that PEN America’s digital media literacy interventions were effective at improving participants’ digital media literacy skills across the board, and improving discriminant trust in news when individuals were motivated to apply the skills they had learned to a behavioral task. Crucially, the intervention evaluations provide early evidence that community-based strategies for reaching individuals – such as recruiting participants through non-profit networks or peer networks – appear to be more effective in improving people’s discriminant trust in news regarding crucial health and political topics. While both the community-based study and the YouGov study demonstrated that the PEN America intervention was effective in significantly improving participants’ knowledge and awareness of digital media literacy skills, we observed stronger effects in participants’ discriminant trust in the community-based sample. We anticipate this effect to be a result of motivational differences in people’s decision to take part in the intervention. People who were recruited through community-based strategies (e.g., receiving an email from a non-profit they support) may be more inherently motivated to learn about these issues, and thus engage more deeply with the intervention materials. In addition, their desire to actively employ the strategies discussed in the intervention may be increased if they perceive themselves as being part of a group of individuals who are similarly motivated; in comparison, participants recruited through panel services may perceive themselves as being alone in completing the workshop and thus less engaged in the material. Finally, people in the community-based sample may be more inclined to take part in the workshop due to a stronger inherent desire to protect their community members, whereas those recruited through panel services may be motivated by financial incentives for completing the study.

Together, these results highlight an important new direction for future research in the misinformation intervention space. Future work should treat the process of recruiting participation in interventions as a valuable research question in order to identify the most effective means of motivating participants to not only complete the intervention, but engage with it deeply and use the skills they learn to protect themselves and their communities.

Another reason the community-based study was more effective in improving the application of digital media literacy skills and discriminant trust may be because there were increased opportunities to engage with intervention facilitators. For example, the interventions were delivered by educators with backgrounds in digital media literacy as well as representatives of the partner non-profits. Being able to see presenters who looked like them and served their community may have improved people’s engagement with the intervention materials. Representation in intervention facilitators and materials may be important to helping community members feel seen, heard, and understood when developing misinformation interventions.

While we note that our measures were predominantly self-reported, they are in line with current best practices and field standards for intervention studies. Our use of the headline task also provides a behavioral measure of participants’ discriminant trust abilities. While additional research should seek opportunities to collect intensive behavioral data from participants (e.g., ecological momentary surveys, evaluations of their computer-log data) to better understand the effect of these interventions on real-world behavior, it is important to recognize the steep cost that comes with collecting such intensive data, particularly from historically marginalized communities. In addition to incurring greater costs to participants’ time, many individuals may feel uncomfortable providing such data – even anonymized – with external organizations or institutions. As a field study and real-world intervention, we believed that we should be aware and responsive of the burdens that research may place on participants, and make methodological choices that prioritize respect for participants’ privacy, comfort, and time.

At a high level, the theory of change that underlies our intervention approach focuses on empowering individuals with the digital media literacy skills they need to navigate the modern information ecosystem and restore trust in credible sources of information. In the long-term, equipping diverse Americans with the skills and resources they need to be resilient to disinformation and capable of finding credible information is a vital part of the solution. Giving people the skills to evaluate the legitimacy of information by checking its sources and cross-checking its claims provides them with a framework to draw on to investigate claims they encounter in their everyday lives. In addition to protecting them from the harms that often come from false beliefs (e.g., COVID-19 or election disinformation), we can also stem the flow of mis- and disinformation by preventing them from sharing it and circulating it further. These interventions provide individuals with the tools they need to not only protect themselves, their loved ones and their communities from disinformation, but also to begin to restore trust in credible sources of information. The spread of false information and increasing distrust of information is a fundamentally social problem: it propagates from neighbor to neighbor, friend to friend, and spouse to spouse when one shares misinformation or distrust. Improving the digital media literacy skills of an individual can produce positive network effects by “breaking the chain.” Efforts to build resilience to disinformation and misinformation should collaborate with communities to meet this collective problem together.

References

Aspen Institute. (Nov. 2021). “Commission on Information Disorder Final Report.” AspenInstitute. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Aspen-Institute_Commission-on-Information-Disorder_Final-Report.pdf

Dodson, K., Mason, J., & Smith, R. Covid-19 vaccine misinformation and narratives surrounding Black communities on social media October 13, 2021. First Draft News. https://firstdraftnews.org/long-form-article/covid-19-vaccine-misinformation-black-communities

Freelon, D., Bossetta, M., Wells, C., Lukito, J., Xia, Y., & Adams, K. (2020). Black Trolls Matter: Racial and Ideological Asymmetries in Social Media Disinformation. Social Science Computer Review, 0894439320914853 https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439320914853

Gallon, K. (2020, October 7). The Black Press and Disinformation on Facebook. JSTOR Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/the-black-press-and-disinformation-on-facebook/

Gu, R., & Hong, Y. K. (2019). Addressing health misinformation dissemination on mobile social media.

Longoria, J., Acosta, D., Urbani, S., & Smith, R. (2021). A limiting lens: How vaccine misinformation has influenced Hispanic conversations online. https://firstdraftnews.org/long-form-article/covid19-vaccine-misinformation-hispanic-latinx-social-media/

Nguyen, A., & Catalan-Matamoros, D. (2020). Digital mis/disinformation and public engagement with health and science controversies: Fresh perspectives from Covid-19. Media and Communication, 8(2), 323-328.

Nguyễn, S., Kuo, R., Reddi, M., Li, L., & Moran, R. E. (2022). Studying mis-and disinformation in Asian diasporic communities: The need for critical transnational research beyond Anglocentrism. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review. https://misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu/article/studying-mis-and-disinformation-in-asian-diasporic-communities-the-need-for-critical-transnational-research-beyond-anglocentrism/

Saltz, E., Barari, S., Leibowicz, C., & Wardle, C. (2021). Misinformation interventions are common, divisive, and poorly understood. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review.

Soto-Vásquez, A. D., Gonzalez, A. A., Shi, W., Garcia, N., & Hernandez, J. (2021). COVID-19: Contextualizing misinformation flows in a US Latinx border community (media and communication during COVID-19). Howard Journal of Communications, 32(5), 421-439 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10646175.2020.1860839

Walther, B., Hanewinkel, R., & Morgenstern, M. (2014). Effects of a brief school-based media literacy intervention on digital media use in adolescents: Cluster randomized controlled trial. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(9), 616-623.

Yousuf, H., van der Linden, S., Bredius, L., van Essen, G. T., Sweep, G., Preminger, Z., … & Hofstra, L. (2021). A media intervention applying debunking versus non-debunking content to combat vaccine misinformation in elderly in the Netherlands: A digital randomised trial. EClinicalMedicine, 35, 100881.

PEN America’s 2021 Community Partnership Programs and this evaluation were supported by Meta.