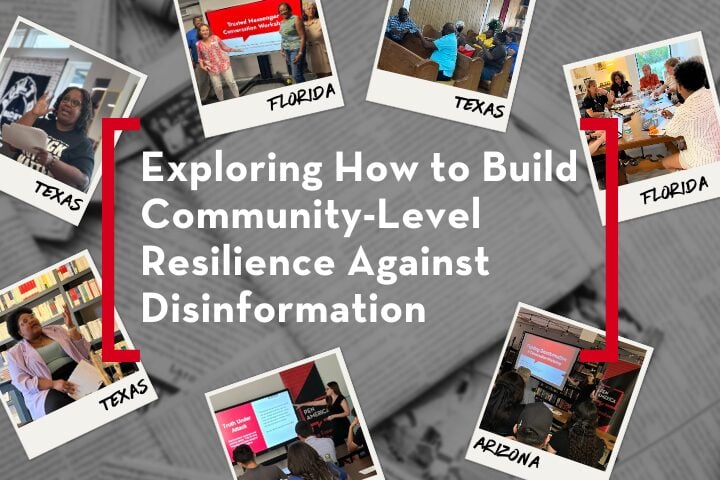

Exploring How to Build Community-Level Resilience Against Disinformation

Key Findings:

Our pilot projects in three metro areas showed the potential of using trusted messengers and a relational organizing approach in building community resilience to disinformation. This theory of change merits additional programming investment.

Both local and national approaches have value for counter-disinformation work. Those seeking to have an impact should consider whether their particular goals are better served by working in a narrower geographical area as opposed to nationally.

Disinformation, and the ability to counter it, is intertwined with factors including trust, polarization, economic conflict, social isolation, prejudice, and mental health. Addressing disinformation in isolation from these factors risks having a less impactful intervention.

Counter-disinformation work must be grounded in an understanding that notions of truth and fact—commonly understood as objective and unmoving—are often shaped by power, privilege, and unconscious bias.

Fighting a Global Problem Through a Local Lens

Read an accompanying essay to this report by Michelle Beaver, Phoenix-based community engagement consultant.

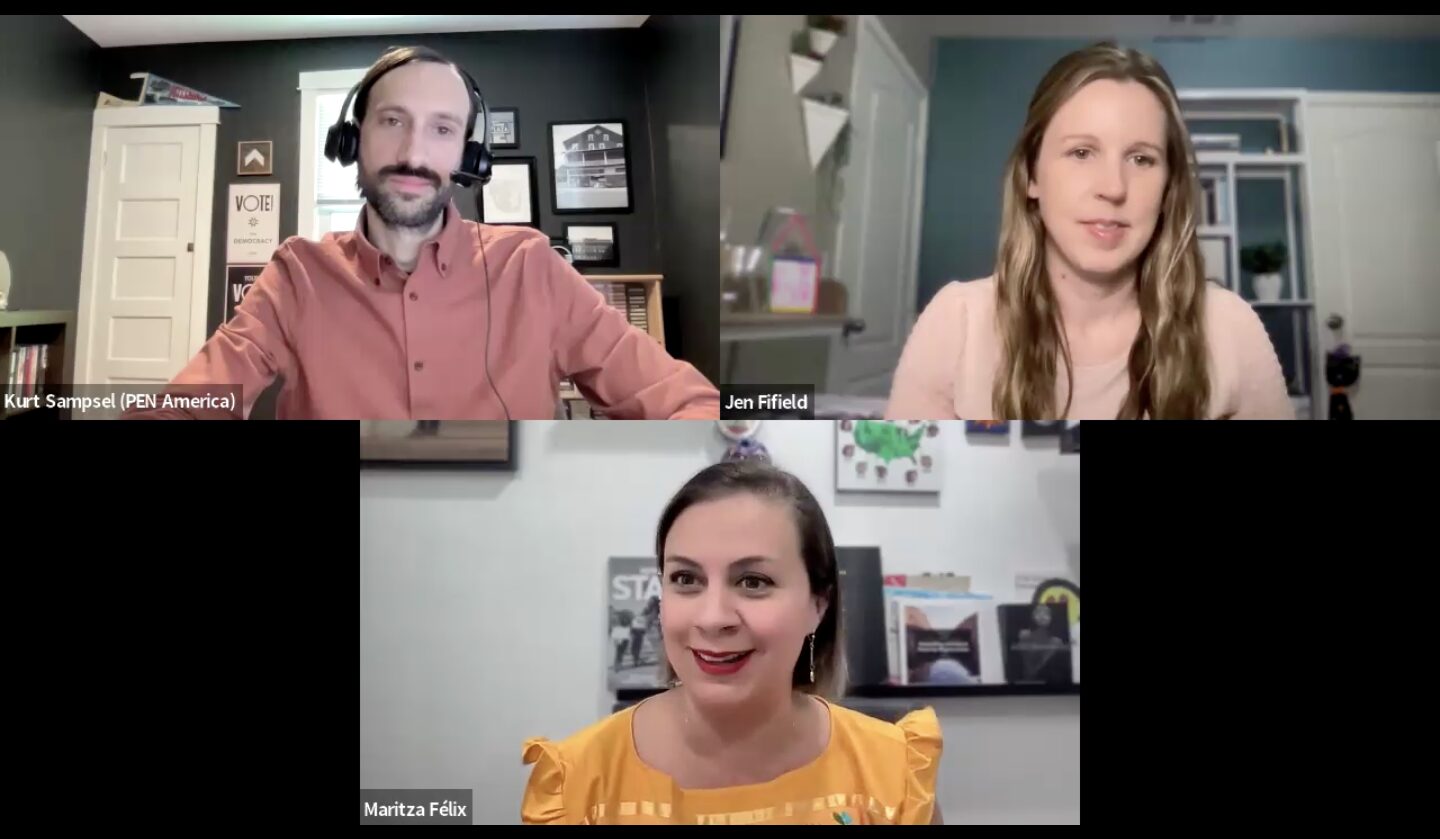

PEN America Experts:

Senior Program Manager, Disinformation and Community Engagement

Manager, U.S. Free Expressions Programs

Introduction

One of the central paradoxes of the 21st century is that while technology has made it easier to access information, that doesn’t mean the public is better informed than ever before.

The decline of legacy news institutions, a dearth of local news, and the emergence of information-sharing platforms whose business models reward inflammatory content can encourage false and misleading information to flourish. Barriers to creating and spreading disinformation, including through new AI tools, have become substantially lower. Meanwhile, cultural factors such as social isolation, political polarization, and distrust in institutions help bad actors to weaponize false claims, through either mobilizing the public in harmful ways or breeding cynicism that undermines democratic participation.

This was especially apparent during last year’s presidential election.

Our work looked at disinformation across the political spectrum. The New Hampshire primaries had an AI-generated robocall simulating then-President Biden’s voice. Weeks later, false claims circulated about Haitian immigrants eating household pets in Springfield, Ohio. Throughout the campaign, each case of breaking news—such as the July 2024 assassination attempt on Trump—provided opportunities for disinformation to proliferate from the political left and right. Additionally, in an election cycle marked by xenophobia, transphobia, and racism, our work evolved to address the role of prejudice in shaping understandings of truth and falsehoods.

These escalating threats to our democracy came as social media platforms were scaling back content moderation and as aggressive legal and legislative pressure chilled and even shut down counter-disinformation research. Efforts to counter disinformation through congressional action, direct engagement with digital platforms, AI technology, legal action, and the support and dissemination of research were stalled. The moment called for new approaches.

In response, PEN America expanded programming for journalists and communities to serve as a bulwark against the spread and acceptance of falsehoods. This report focuses on PEN America’s Disinformation and Community Engagement (DCE) program, which explored a novel approach: tackling a global problem by investing in local and regional initiatives to distribute trustworthy information, lifting local perspectives about how disinformation affects communities and how best to combat it, and developing local capacity to consume information critically.

To pilot this set of interventions, we focused on three rapidly growing, diverse metropolitan areas where PEN America already had regional chapters: Miami, Dallas–Fort Worth, and Phoenix. We approached these Sunbelt cities as bellwethers for how disinformation operates, believing that with the challenges each faced and the ways in which these communities reacted to our programming, the three could provide learning experiences for one another and for communities across the nation. We understood the difficulties involved in scaling these types of locally based programs, but were heartened by the success similar approaches had seen.

While PEN America is a nonpartisan organization, the issues that were top of mind for many of our partners and audiences, unsurprisingly, often were connected to a highly polarized presidential election season awash in disinformation. It was also an environment with constant charges and countercharges of disinformation, from both Democrats and Republicans—all as the term “disinformation” itself was being weaponized for partisan ends. And now, although the election is behind us, the supply of—and the demand for—false information and viral conspiracies has not abated.

Indeed, in 2025, deceptive information is all too often a driving tool in advancing key parts of the administration’s agenda in areas it is targeting, such as education, the press, and foreign assistance, or in its claims and enforcement around anti-discrimination laws and decrees. For example, we’ve seen this with false or egregiously exaggerated claims about fraud in government programs and spending. Moving forward, it seems clear the American public will need additional disinformation resilience as false and misleading information increasingly flows not just from known provocateurs and propagandists but also from sources and institutions long viewed as authoritative.

The question of what information sources are trustworthy often proved to be complex in our community-based work, and that challenge should be recognized by groups working on these matters. For example, key parts of our webinars and trusted messenger work were built around what makes a source reliable, or, in some cases, what media sources may be more reliable than others. However, for many individuals, and particularly those from historically marginalized backgrounds, experiences with otherwise reliable high-quality media outlets are mixed. For these individuals, the “commonly agreed-on” truth can equate to long-held dominant and prejudicial narratives. Organizations working in counter-disinformation must be willing to fight disinformation, including unconscious biases that uphold systemic inequities, regardless of the source. As the current administration escalates attacks on vulnerable communities and broadly seeks to silence or erase anything it considers an effort to support diversity, equity, and inclusion, this learning has become more critical.

In the present moment, counter-disinformation work has fallen out of fashion. In large part, that’s because it’s proven to be a more distributed, multifaceted, and stubborn problem than it may have appeared only a few years ago to the experts in the field and those funding it. What’s more, efforts at combating disinformation and resisting government-imposed orthodoxies are being preemptively labeled, often without merit, as the “real threat” to free speech and the Constitution. The purveyors of disinformation appear to have little incentive to stop.

But this is why more investment and effort in information science is needed. With the field under attack from the current federal administration and some members of Congress, among others, many key organizations and individuals previously involved in work researching and advocating around disinformation have been forced to shut down or have backed away rather than risk becoming targets. The need for more concerted efforts in this area to help support a more informed society could not be clearer.

Goals and Contributing Activities

When launching the community-focused disinformation program in 2022, we established goals that were small in number but large in ambition.

First, we wanted to advance our understanding of how to effectively and efficiently equip communities for resilience in the face of disinformation. Second, we hoped to establish a pipeline to bring our learnings into the policymaking process to support free expression–friendly approaches to tackling disinformation.

To those ends, we pursued a set of key activities:

- A “trusted messengers” initiative that trains people to have difficult conversations promoting the broadening of news and information consumption: We wanted to see whether a trusted messenger approach that leveraged preexisting interpersonal trust, which had proven successful in other contexts, could work in building resilience to disinformation among friends, family, coworkers, and neighbors vulnerable to its influence. To do so, we chose as a proxy for vulnerability to disinformation an individual’s reliance on a single or small number of news and information sources that confirm preexisting beliefs. Research has shown this practice tends to spread and reinforce mis- and disinformation—regardless of political affiliation—in contrast to seeking out diverse, high-quality information.

- Subgrants to support regional counter-disinformation initiatives: Recognizing the constraints on a national organization working at the community or regional level, we invested in regional nonprofit organizations with established audiences and positions of trust that sought to pilot new initiatives and measure their impact.

- Instructional webinars on disinformation resilience: Responding to a need for learning, we created training webinars on disinformation-related topics, including cognitive bias, fact-checking standards, and the role of influencers in our media landscape. Guest experts from Miami, Dallas, and Phoenix lifted up perspectives and needs from the communities we focused on.

The bulk of this report shares findings, data, and perspectives from these activities, as well as suggestions for how similar programming could build on these learnings in the future.

Counter-Disinformation Activities

1. A trusted messengers initiative that promotes healthy information consumption

Landscape Overview

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

This quote, poignantly offered by author and activist James Baldwin, stretches along the side of a towering glass building in the center of Phoenix’s Roosevelt Arts District. The mural of Baldwin, which stands nine stories, sits five blocks from Arizona State University’s Cronkite School of Journalism, where students, academics, and journalists work each day in pursuit of innovating in a critical field that is losing the public’s trust.

We landed in Phoenix on a January morning, finding warm weather that was a sharp contrast to New York and Washington, DC, where two of PEN America’s offices are located. We were meeting with community leaders to discuss potential grassroots-level interventions ahead of the 2024 election, amid lingering anxiety remembering Maricopa County’s position four years earlier at the center of “Stop the Steal” conspiracy theories.

Phoenix was not the only Sunbelt city where organizers, journalists, and grassroots leaders were bracing for an onslaught of disinformation. January’s convening in Phoenix was the first in a series with community leaders in our three target cities, that also included Dallas–Fort Worth and Miami. At each event, we brought both new and existing partners in PEN America’s disinformation work together to discuss emerging challenges.

While the local contexts varied for these convenings (differing narratives taking hold, differing avenues for the spread of information, differing political priorities), there were universal themes. Community leaders in Texas, Florida, and Arizona expressed:

- A desire for national organizations and funders to see local-level efforts as critical work worthy of their support

- A sense that pro-democracy work and efforts to counter polarization are intricately linked with counter-disinformation work

- A belief that person-to-person interventions are critical—and yet are often uncomfortable or frightening to approach

In this political moment, while Americans’ trust in media and political institutions remains at a historic low, there is one key resource that Americans trust for information: friends and family.

A 2023 Economist/YouGov poll found 65 percent of respondents said “friends and family” when asked who they trust most for election-related information. This level of trust held almost evenly among members of each political party (with a slight decrease among self-identifying Republicans). Meanwhile, fewer than half of respondents among both parties trusted poll results, the news media, social media, or political campaigns for election information. Based on this emerging data—and on key takeaways from our community convenings—we settled on a driving question for shaping our approach: How could we leverage the power of interpersonal trust at the community level to foster resilience to disinformation?

Relational Organizing and Counter-Disinformation

In a 2022 analysis, the Union of Concerned Scientists asserted that “building relationships through one-on-one conversations over time has proven to be a highly effective way to inoculate others against disinformation, share credible information, and mobilize people into action so that solidarity grows and disinformation campaigns are thwarted.”

This sort of mobilization through peer-to-peer engagement is at the heart of a practice known as “relational organizing.” In a 2020 article for Mother Jones, Pema Levy defines relational organizing as “simply facilitating conversations between friends, family, neighbors, and co-workers. Instead of relying on traditional strategies like door knocking, phone calls, or texts from strangers, [relational organizing] harnesses existing relationships to mobilize voters.”

Relational organizing is often interwoven with other methods for political education and mobilization, such as voter registration, civic education, field organizing, digital organizing, and deep canvassing. In recent years—particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic made traditional door-to-door efforts nearly impossible during the 2020 election cycle—relational organizing has increasingly become a pillar of campaigns looking to engage broad swaths of voters, especially those who are harder to reach or more difficult for campaigns to sway and mobilize. Indeed, the effectiveness of relational organizing in an electoral context has been demonstrated by both parties in recent elections.

Building on these findings, we developed a central question for an experimental pilot program:

Can grassroots organizing methods—particularly those proven to be successful in an electoral context, such as relational organizing—be utilized to foster more resilient communities in facing the spread of disinformation at the local level?

Key Data Points

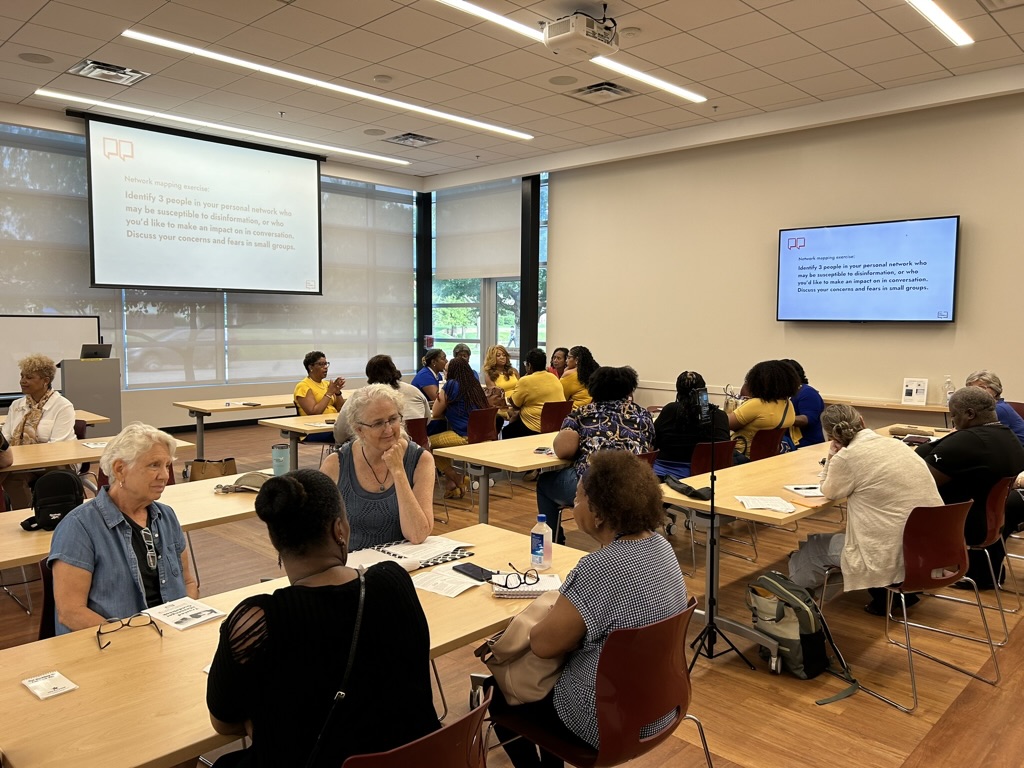

Through 23 Trusted Messenger workshops over 9 months, primarily in Phoenix, Miami, and Dallas, we trained, organized, and empowered 501 trusted messengers to encourage someone close to them to broaden their news diet as a proxy for fostering resilience to the spread of disinformation.

Given our initiative’s focus on activating community members already engaged or interested in the issue of disinformation, we focused more on measuring our training’s impact on the trusted messengers themselves, rather than examining the messengers’ impact on the information consumption habits of the individual or individuals they subsequently sought to intervene with. Through surveys, we tracked trusted messengers’ self-reported sense of empowerment—along with various anecdotal benchmarks—as a metric for gauging impact.

On a scale of 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest), trusted messengers were asked to rate their sense of comfort or preparation when entering difficult conversations about disinformation and news consumption with loved ones. They provided ratings at the beginning of each workshop, at the conclusion of each workshop, and (for the first four months of programming) within two weeks after the training. Here’s what we found:

- Total number of workshop entry surveys received: 165

- Total number of workshop exit surveys received: 150

- Average self-reported sense of empowerment, pre-training: 6.31

- Average self-reported sense of empowerment, post-training: 8.18

- Average self-reported sense of empowerment within two weeks, going into conversations: 7.26

Trusted messengers’ confidence rose post-training and remained elevated. The average level of self-reported sense of empowerment dipped within two weeks after the training, but remained higher than pre-training levels. All exit survey respondents said they would recommend the community workshop to others.

While our evaluation showed that bringing together friends, loved ones, and acquaintances to leverage existing interpersonal trust can be effective in sparking conversations, the data we gathered was limited. However, by extrapolating data collected in the first four months of programming, we estimate that our trusted messengers prompted roughly 1,300 conversations with individuals in their personal networks from June 2024 to February 2025.

Trusted Messengers Initiative Key Findings

- A trusted messenger approach to fostering grassroots-level resilience to disinformation has strong potential for wider impact. A scaled program measuring impact on both cohorts—trusted messengers and the peers they engaged with—is warranted based on this pilot’s promising results.

- Issue-based organizations, public libraries, nonpartisan government offices, and civic organizations play an important role in filling information gaps.

- The same program in Dallas will look different in Phoenix. A commitment to taking a tailored approach to programming based on local context is key. That means, in developing programming, taking the lead from grassroots organizers and community leaders doing on-the-ground work—particularly as communities are more likely to engage in counter-disinformation work if it’s conducted under the umbrella of existing issue-based work.

Longer-term, sustained investment in capacity-building for community organizations and grassroots organizing efforts is key—and has particular value when done not during election cycles.

Overview of Trusted Messenger Programming

The intention of each Trusted Messenger workshop was to equip attendees with a better understanding of how disinformation spreads, paired with useful conversation tactics to intervene against those who may be susceptible to falsehoods, particularly those who get their information consistently from only one or a small number of similar sources that serve—and are often chosen—to confirm preexisting beliefs. Each training was framed by a request that attendees use their learnings to urge friends or family members to adopt strategies to protect themselves from false information. The specific request (“hard ask”) given to trusted messengers was to encourage at least one person to introduce a new news source into their media diet—particularly one that introduces a new perspective—to break out of information echo chambers and develop a habit of fact-checking or questioning information they consume.

In each target city, we brought a local community organizer onto our team to conduct outreach with local organizations, take a moderator role during workshops, and steer our broader approach to the needs of their community. Each Trusted Messenger workshop was hosted in partnership with a local organization, business, or community group, enabling us to reach diverse audiences within each city while uplifting the work of local organizations. Our workshops drew librarians, journalists, union members, educators, community organizers, seniors, students, and others. Partners were offered a small honorarium for their support.

Dallas–Fort Worth Workshop Hosts/Partners:

Wayside Missionary Baptist Church, Dallas–Fort Worth NAACP, Dallas Public Library, BLACKLIT Bookstore, Tarrant County College, Tarrant4Change

Miami Workshop Hosts/Partners:

United Teachers of Dade, Miami-Dade NAACP, Underrepresented People’s Positive Action Council (UP-PAC), Scott Lake Neighborhood Crime Prevention Group

Phoenix Workshop Hosts/Partners:

Goodmans Furniture Store, Grassrootz Bookstore, Boys Hope Girls Hope, Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, Chaparral High School, Glendale Union High School

Each workshop was broken into two halves: a more general education portion followed by a training on how to approach difficult conversations. Each half concluded with group exercises.

In transitioning from the general education portion (covering the difference between mis- and disinformation, key risk factors for news consumers, an overview of what diverse news diets may look like, and the relationship between identity-based biases and disinformation), we posed a question to attendees:

Ask yourself, “Does anyone in my personal network come to mind who might be particularly susceptible to the spread of disinformation?” What fears or concerns do you have about conversing with this person about disinformation?

Community members often came to our workshops with personal stories in mind—or had little trouble recounting moments of difficulty, frustration, or even outrage when it came to political conversations shaped by disinformation narratives. Whether it be the impact of the “Stop the Steal” campaign creating conflict between neighbors, disinformation regarding gender identity pushing apart parents and children, or disinformation regarding COVID-19 vaccines fracturing family bonds, painful stories flowed from our workshop attendees, who thought of coworkers, parents, childhood friends, students, and neighbors. This group discussion routinely provided space for validation and connection. The bonds developed in this session carried into the workshop’s second half and at times continued after the workshop’s conclusion.

After this large group discussion, we transitioned into the conversation training portion of the workshop. We covered prompts for preparation ahead of a conversation, how to navigate the conversation in process, strategies for dealing with conflict, how to consider the role of trauma and sensitivity when discussing news consumption or disinformation narratives, and suggestions for follow-up (keeping in mind that no one’s mind is likely to be changed after a single conversation).

At the conclusion, attendees were asked to break into pairs to role-play the same kinds of conversations we were encouraging them to have (We asked that attendees choose people who made the most sense to them, which could exclude those who may need a more intense intervention). Prompts for the exercise included:

- Partner A doesn’t consume news. They think the news is exhausting to keep up with and that the climate is too tense. Partner B, try to help them see that being informed is important. Encourage them to try a habit of checking in with the news.

- Partner A believes that climate change is a conspiracy and is not true. They think this because of what they see on social media. Partner B, try to help them see that they may have fallen down a rabbit hole that is shaped by a particular bias. Encourage them to broaden their news diet.

- Partner A, base your challenge off the person in your network who you identified earlier in today’s workshop. Partner B, try your best to intervene.

Each newly trained trusted messenger received a copy of PEN America’s Trusted Messenger Guidebook (cowritten with Celeste Sepessy, assistant teaching professor at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, and program manager at the ASU News Co/Lab) to support them in approaching conversations. We provided “A Guide to Developing a Healthier News Diet” as an additional resource as well.

Community Voices on a Trusted Messenger Approach

Case Study #1: Dallas, Texas — Barbara James

Barbara James found herself encountering conversations about the then-upcoming presidential election everywhere she went, from the barbershop to the grocery store. The heated election cycle—shaped by assassination attempts, a candidate switch, a historic nomination, and more—made PEN America’s counter-disinformation workshop appealing.

While at the workshop, James identified a friend as the community member in her network she’d like to reach out to. She chose this person based on the fact that while they had many shared values and opinions, there were a handful of issues they did not agree on. From James’s perspective, several of those opinions were grounded in her friend’s reliance on one news source.

Drawing from lessons learned at our workshop, she approached her friend a handful of times, encouraging them to introduce new sources into their news diet. James told PEN America she “would say something like, ‘Well, instead of just listening to channel XYZ,’ without mentioning the network, I would just suggest that it would be a good idea to try to mix up different news broadcasts so you can get a different perspective that’s presented by another network instead of just listening to one. Then I’d suggest some that I felt were more reliable sources.”

These conversations were backed up with action. James told PEN America that she and her friend began watching presidential debates and follow-up news broadcasts together, where they would make note of the different information shared by candidates and pundits. In the case of wide differences between information shared or claims made on particular issues, they made a point of fact-checking.

“I realized that it wasn’t my role to try to persuade anybody to change their minds to be in agreement with me. I would just say, ‘That’s what I’m not trying to do. I’m not trying to persuade you to be in agreement with me.’ And I would say, ‘I’m just trying to make a suggestion into what I think would be a more informed source of diverse opinions of the news that you’re taking in, versus just relying on the one source you’re using.’”

James believes that the most valuable part of the workshop was obtaining the general disinformation education, learning strategies for having effective conversations, and receiving the Trusted Messenger Guidebook.

Case Study #2: Miami, Florida — Jaqueline Gil

Jaqueline Gil became aware of our Trusted Messengers initiative through a local partner, United Teachers of Dade. It piqued her interest, as she was beginning to see the effects of disinformation on her community up close, having decided to run for public office.

That month’s Trusted Messenger workshop consisted mostly of educators working in the Miami-Dade County school district. While there were a number of disinformation narratives to choose from, there was one in particular that Gil and others were concerned about: false narratives about classroom content in schools. In choosing a specific community member to intervene with, Gil chose a professional colleague of hers. Gil was concerned with what she interpreted as an overreliance on social media.

Finding common ground as mothers of children in the military, Gil intervened with this colleague and discussed news diets, as well as book bans and educational gag orders. While conversations regarding political issues were common for the two, Gil credits our training as having prepared her with a better understanding of disinformation resilience and for providing the language needed to convey its importance.

“She’s going to several sources now—not just what you read on social media,” said Gil. “She’s actually sent me several messages or several quotes, and tells me, ‘So what do you think about this? Do you think this is valid?’ So, I think that she picked up on the fact that there is a lot of disinformation out there, and that sometimes we don’t need to listen to everything that we acquire on social media. It’s better to do research and find out the facts before we go and share with other people, before [falsehoods] go rampant.”

Gil also took these learnings to engage with others in her community. As a candidate for public office, she found herself navigating difficult conversations about disinformation while going door-to-door.

“While I was canvassing, a gentleman approached me and asked me about how I felt about teaching gender identity. And I said, ‘Sir, that doesn’t exist. Gender identity curriculum does not exist in Miami-Dade County Public Schools.’ And he tells me, ‘Oh, I saw it on the news.’ And then I explained to him, ‘Well, that’s what’s called disinformation. They’re trying to divert you from the facts.’”

While some conversations went well, that wasn’t the case for all, particularly as she branched out farther into the community. Gil said she believes additional support on how to deal with conflict in conversation would be valuable.

Case Study #3: Phoenix, Arizona — Corey Harris

Corey Harris, commissioner for Phoenix’s Military Veterans Commission, has always tried his best to see things from all angles—making a point of considering the perspective of those on the other side of the political aisle. However, he said the worsening impact of disinformation is concerning.

“Once you’re locked into an emotional channel, how do you get out? How do you help someone see a way out of a trap that may be detrimental to them?”

Harris attended a workshop because of the trust he had in PEN America’s local organizer in Phoenix.

In considering who to speak to about disinformation and news consumption, Harris identified a family member affected by disinformation regarding transgender identity. Harris had attempted conversations with this family member before but hadn’t found much success. And while he took away critical learnings from the disinformation education portion of the workshop, he said the conversation guidance around news consumption was most important.

In his conversations, Harris tried to intervene through offering targeted critiques of particular news sources. He found himself leaning on language such as “It’s not that I don’t trust you. I don’t trust where you’re getting your news.”

He told PEN America, “I see some of the far-right argument pieces from how he argues, and [other times he’s] really well researched and knows what he’s talking about.”

And while a larger shift in news consumption did not occur, Harris said the workshop had a positive impact on the way both he and his family member approach each other in conversation.

“I think that’s probably the biggest leap since the workshop, is just saying, ‘I’m not just going to sit here and be reasonable to everything you’re saying, but I also want to figure out how we can work through this without yelling, and find a different way.’ And he seems amenable to it. I can’t make him do anything. It’s really up to him if he wants to play along, but it seems like he’s open.”

Looking Back on the Trusted Messengers Initiative

One benefit of relational organizing work, and of the broader theory of empowering trusted messengers, is the investment made in bolstering a community’s long-term organizing capacity. The tools offered to trusted messengers around person-to-person intervention, paired with bridge-building between community members and local organizers, support the existing infrastructure within a community.

For future iterations of this work, here are recommendations for supporting that infrastructure more effectively:

- For national organizations, hiring local organizers is critical for shaping programming. Trust must be built between the community and your organization or campaign.

- Conducting programming outside of election years has particular value, as communities may be less inundated with rapid-fire news headlines during these periods. On the flip side, however, grassroots initiatives may find less support from national groups or funders outside election cycles.

- If right for your program, consider methods for data collection that track the impact of conversations or behavioral change regarding the trusted messenger’s hard ask.

- Consider a cohort model or follow-up exercises to keep trusted messengers’ sense of empowerment and connection elevated over longer stretches of time.

- There is an interest in ground-level education in understanding broader news diets. However, when giving trusted messengers a hard ask to act on, centering more diverse news diets may not be as effective as a more intentional pairing with the disinformation around particular issues that the community or individual trusted messenger cares about. Take cues from community organizers to build bridges from disinformation to these issues.

- Connect community members and local newsrooms by inviting journalists to attend and participate in the programming.

- Consider robust partnerships with local institutions, such as newsrooms, public libraries, issue-based organizations, and nonpartisan government offices.

- Determine your audience. Is the content of your training meant to give tools to all community members, or is it intended to train community leaders or organizers to bring learnings into the spaces where they’re already engaging community members?

- Consider whether you’re positioned for effective new audience recruitment, or if pursuing captive audiences is a better approach.

- Translate trainings and resources—with regard to both language (such as English to Spanish, English to Haitian Creole) and platform (such as WhatsApp).

2. Subgrants to support regional counter-disinformation initiatives

Between the 2022 midterms and 2024 presidential election, we concluded that subgrants to trusted and impactful local organizations would deepen the impact of our counter-disinformation work in Miami, Dallas–Fort Worth, and Phoenix. As a national organization aspiring to work at regional, local, and community scales, we understood that partnerships would be essential. We recognized that some of our goals would require a considerable level of regional credibility and cultural competency.

In the first phase of this program (2022–23), collaborations between PEN America and local organizations were informal. Seeing our role as primarily that of a convenor, we invited local experts to share their perspectives on panels. To learn more about how communities experience disinformation, we interviewed journalists and community leaders and included their perspectives in 2023’s Building Resilience report. We also responded to requests for support, such as when PEN America helped the Texas Tribune translate its voter guides into Tagalog and Vietnamese.

But in fall 2023, with the presidential election year approaching, our community contacts wanted a more formal relationship with us that would enable them to experiment with possible solutions.

“We’ve had many conversations with national organizations like yours,” one of our Miami contacts explained, “and nothing is getting done.”

Why Grants?

Our decision to award grants was informed by conversations with our contacts. In a series of informal discussions, we learned that a few organizations had developed counter-disinformation initiatives they were excited about. When we asked what kind of support and collaboration would be most helpful, they said funding was an ongoing challenge in their work.

We decided to pursue a two-part strategy. We would offer grant funding to help the organizations run their initiatives or pilot new ones. And we would amplify the organizations’ work, helping to bring their resources, perspectives, and learnings to counterparts in our other program locations and, indeed, a national audience.

To select organizations for grant funding, we considered these criteria:

- Which initiatives that we profiled in our Building Resilience report seemed especially promising and scalable?

- Which organizations had established brands and positions of credibility with sizable audiences?

- Which organizations and initiatives would focus on serving people who have historically faced barriers to participating in civic life?

- Which organizations had language skills and cultural competency out of reach for PEN America?

- Which organizations could achieve local impact while producing materials that would be useful for others beyond the city and region?

We ultimately chose to fund one nonprofit organization serving each of the three regions: Factchequeado for Miami, the Texas Tribune for Dallas–Fort Worth, and Conecta Arizona for Phoenix.

Getting Facts to Spanish Speakers with Factchequeado

Co-founded in 2022 by two journalists, Laura Zommer of Argentina and Clara Jiménez Cruz of Spain, Factchequeado is a nonprofit based in California with operations in Miami, among other 23 states, that provides Spanish-language journalism, fact-checking, and media literacy resources for Latino and Hispanic communities in the United States. Although Factchequeado’s team is global and its focus national, PEN America selected the organization as best positioned to serve the Miami region, where it has a number of partners and where Managing Editor Ana María Carrano isbased.

A true information hub, Factchequeado is best known for its frequent fact-checks, but it also produces training resources for journalists covering Latino communities, leads talks and forums with opinion leaders and news organizations, and publishes media literacy materials on topics like how to identify content produced by AI.

Perspective

Tamoa Calzadilla, former editor in chief of Factchequeado.

What we supported

- Strengthen Spanish-language fact-checking capacity among journalists and fact-checkers by establishing a weekly coalition meeting, bringing together Factchequeado partner organizations to share disinformation resources

- Expand the reach of Factchequeado’s content by producing both Spanish and English versions for dissemination among radio stations in Florida

- Help Latino and Hispanic audiences learn media literacy concepts by producing a Spanish-language media literacy course on WhatsApp

Some of Factchequeado’s outcomes

June 2024: Factchequeado publishes its WhatsApp media literacy course, #FactChallenge. Since then, information about the course has reached 106,000 accounts on Facebook and 25,000 accounts on Instagram, and 260 participants have enrolled in the course. In addition, LatAm Journalism Review, part of the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas at the University of Texas, recognized #FactChallenge as one of the “10 groundbreaking news projects that made an impact in Latin America.”

Aug. 2024: PEN America publishes an interview with then editor in chief Tamoa Calzadilla as part of our Facts Forward series of interviews with journalists combating disinformation.

Aug. 2024: Cofounder and CEO Laura Zommer serves as a guest speaker in PEN America’s webinar “How Fact-Checking Works—and Why It Matters.”

Oct. 2024: Factchequeado holds an event, “La verdad no tiene partido” (“Truth is nonpartisan”), at Florida International University in Miami. In attendance are 50 journalists, community leaders, and disinformation experts, including representatives of the Pew Research Center, The Washington Post, Univision, the News Literacy Project, American Press Institute, Digital Democracy Institute of the Americas, and Proof News.

Nov. 2025: Factchequeado provides over seven hours of livestreamed fact-checking and results on election night.

Dec. 2025: PEN America publishes Factchequeado’s “Cómo detectar desinformación generada por inteligencia artificial (IA),” a Spanish-language guide to identifying AI-generated content.

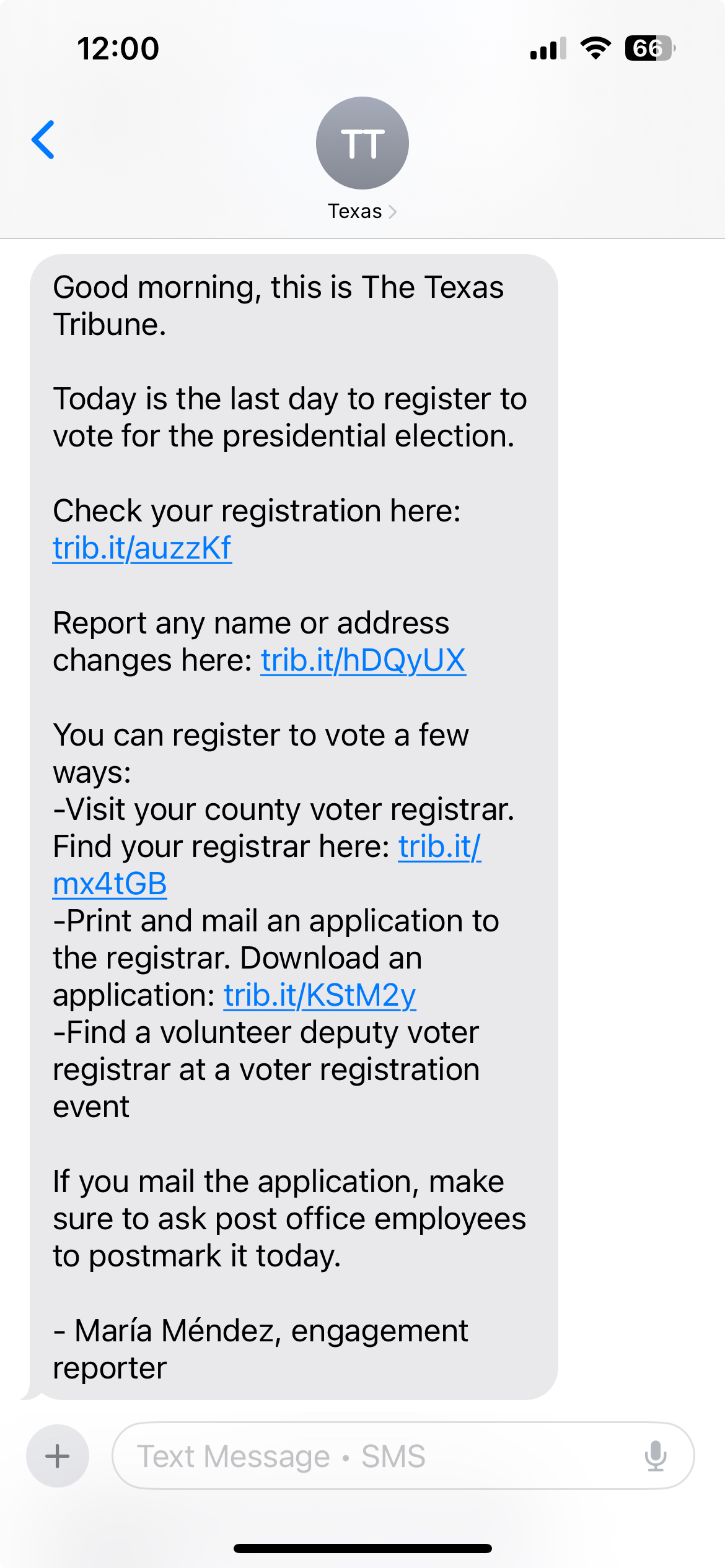

Meeting Voters Where They Are with the Texas Tribune

The Texas Tribune is a digital statewide nonprofit news organization serving Texas. It connects with audiences through service journalism projects as well as live events throughout the state, including the annual three-day Texas Tribune Festival.

With a mission statement that emphasizes advancing democracy and supporting civic participation, the Tribune has been recognized for its voter guides, which share nonpartisan, fact-based information about how to vote in a state known for frequent changes to voting procedures. Although the Tribune is statewide and headquartered in Austin, it provides substantial coverage for the Dallas–Fort Worth region.

Perspective

Read more about Texans’ attitudes about democracy and civic information from Matt Ewalt, senior director of events and live journalism at the Texas Tribune.

What we supported

- Facilitate a listening session in the Dallas–Fort Worth region to identify community members’ most common questions and information needs about voting

- Provide voting information to the public using an automated text message service

- Provide voting information to the public using an AI-powered chatbot accessible through the Tribune’s website and trained on the Tribune’s voter guides

- Provide voting information through a printed voter guide, with emphasis on young and new voters; work includes partnering with local nonprofit and community organizations to distribute the guide

Some of the Texas Tribune’s outcomes

Jan. 2024–Nov. 2024: Through a text messaging platform, the Tribune provides information about voting in Texas to a list that grows to 1,265 recipients over the course of 2024. The Tribune sends a total of 21 bulk text messages to this list, including reminders about voter registration deadlines, information about available voting methods, and summaries of election results. In addition to these bulk text broadcasts, the Tribune responds to more than 70 unique questions about voting via the Voting Help Desk.

May 2024: Senior director of events and live journalism Matt Ewalt moderates a 60-minute listening session in Dallas to better understand local residents’ attitudes about democracy and their civic information needs.

Aug.–Nov. 2024: In addition to its main voter guide, the Tribune publishes specialized guides. Over 83,000 people view the young voters guide, 39,000 view the guide to voting by mail, and about 4,000 view the guide for people with disabilities. The Tribune estimates that 367,885 view its election coverage overall.

Sept.–Oct. 2024: Service and engagement reporter María Méndez and director of audience growth and engagement Matt Adams lead an initiative to distribute printed voting information to communities throughout Texas. PEN America supports this effort by offering our community contacts free copies of the printed materials, and ultimately Tribune staff distribute 3,500 flyers and stickers to public libraries, food banks, and other community organizations.

Oct.–Nov. 2024: Tribune staff pilot an AI voting assistant, allowing people to ask questions about the voting process and receive responses from an AI-powered chatbot trained on the Tribune’s voter guides.

Nov. 2024: The Tribune holds a postelection debrief event, “What Just Happened? Unpacking the 2024 Texas Election Results,” in Dallas. In attendance are 55 community leaders and philanthropy professionals. Tribune CEO Sonal Shah and editor in chief Matthew Watkins share results from the Tribune’s civic information campaigns, talk about the impact of disinformation and deepfake content, and analyze election results from around the state.

Nov. 2024: PEN America publishes an interview with Matt Ewalt, senior director of events and live journalism, as part of our Facts Forward interview series.

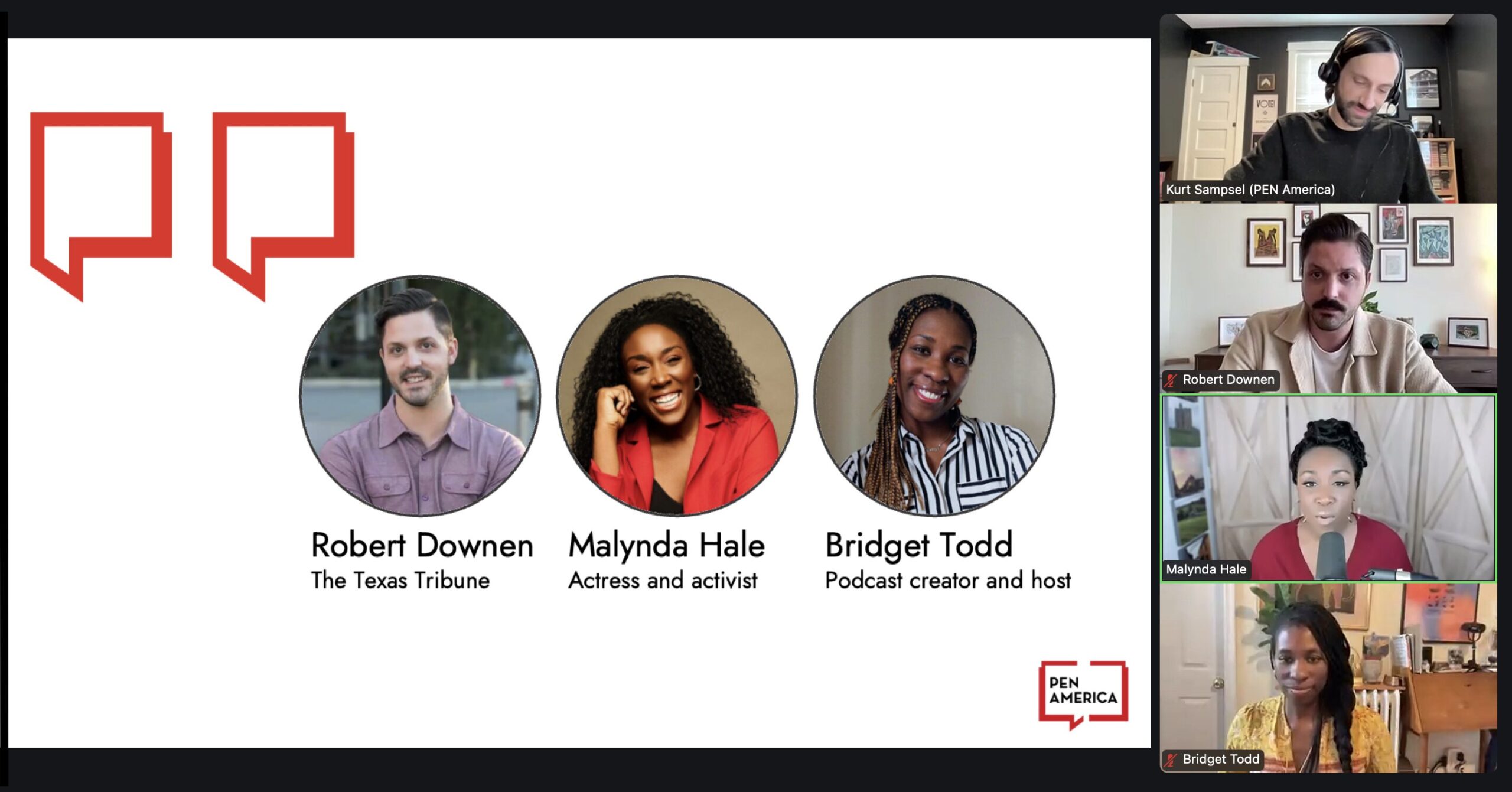

Jan. 2025: Democracy reporter Robert Downen serves as a guest speaker at PEN America’s webinar “How Influencers Are Changing Our Information Ecosystem.”

Making a Safe Space for Conversation with Conecta Arizona

Based in Phoenix, Conecta Arizona is a nonprofit news organization that provides information and community support for an audience of over 100,000 people, predominantly in Arizona and the neighboring Mexican state of Sonora. Maritza Félix, its founder and director, created Conecta Arizona in May 2020, at the height of the pandemic, as a WhatsApp family group chat for sharing information—and debunking falsehoods—about the virus. As the group grew, Félix recognized that the general public would benefit from such a service, leading her to transform Conecta into a full-fledged news organization.

Viewing journalism as a service, Conecta Arizona provides information on WhatsApp, through a newsletter, a website, a podcast, and a radio show. Its trademark service is its cafecitos—casual conversations over coffee—that take place every weekday on WhatsApp, allowing community members to hash out current events and topics of interest in a community setting. By providing a safe space to have conversations, the cafecitos allow participants to ask sensitive questions, test the veracity of information they’ve been exposed to, and refer each other toward trustworthy information.

Perspective

Read about how Conecta Arizona uses community to debunk false information from Maritza Félix, founder and director of Conecta Arizona.

What we supported

- Increase the impact of Conecta Arizona content by producing higher-quality Spanish content and translations that incorporate cultural sensitivity and context, ensuring that Spanish content resonates with target audiences

- Improve the responsiveness and timeliness of fact-checking capabilities by establishing an in-house team for investigations

- Improve community members’ access to trustworthy, authoritative information by establishing a network of experts on topics, including immigration law, healthcare, education, and civic engagement, where community members can directly engage with experts

Some of Conecta Arizona’s outcomes

2024: Conecta Arizona hosts at least one WhatsApp cafecito each week that features a guest expert, providing space for community members to share information and engage with subject matter experts. On average, 69 questions are posed each session, and hundreds of messages are exchanged.

Sept. 2024: PEN America publishes an interview with founder and director Maritza Félix as part of our Facts Forward interview series

construimos hoy.” Photo by Daniel Robles/Conecta Arizona.

Oct. 2024: Conecta Arizona and 12 News host an event, “Voto latino: El mañana lo construimos hoy” (“The Latino vote: We build tomorrow today”), at Greenfield Academy in Phoenix. Speakers include Arizona Secretary of State Adrian Fontes and representatives from Mi Familia Vota, Chispa Arizona, Fuerza Local, RAZE, and Aliento. About 100 people attend, and 40,000 view the livestream.

Oct. 2024: Maritza Félix serves as a guest speaker in PEN America’s webinar “Understanding Election Disinformation: What Voters Need to Know.”

Oct. 2024: In partnership with Over Zero, Conecta Arizona runs a social media campaign in English and Spanish to inform audiences about the risk of political violence ahead of the election. PEN America publishes an article about this effort.

Oct. 2024: Félix participates in “Local Voices Fueling Information Integrity,” an online briefing hosted by PEN America, to provide her perspective on how disinformation impacts the Phoenix area. The recording is shared with members of Congress and their staff to inform their work.

Looking Back on the Grants

Ultimately, these three subgrants proved to be an effective framework for turning informal collaborations into formal partnerships. Ensuring that partnerships are a two-way street, with opportunities for feedback, is important when national organizations come into communities and seek to work with local organizations.

When PEN America launched this program, we envisioned a different kind of partnership, with PEN staff members joining local community leaders in coffee-fueled, late-night strategy sessions to brainstorm messaging to respond to viral falsehoods. But through the process of listening, we came to recognize that the people we hoped to work with didn’t need that sort of help. They knew what messages to send, how to send them, and who to send them to. They primarily needed financial help to expand their impact. In response, we provided funding and amplification. This demonstrated the value of listening to local groups and providing whatever support they feel will be most helpful.

Additionally, although we are proud of the regional outcomes we achieved, we concluded that unless your goals require working in a limited geographic area, focusing counter-disinformation efforts on specific locations can be unnecessary and has the potential to limit impact. Spread primarily through electronic communication, disinformation isn’t constrained by zip codes or city boundaries, meaning mitigation efforts usually don’t need to be either. Although physical geography can factor into why disinformation is created, how it spreads, and what makes it effective, there are other, more salient factors that must be considered, including audience demographics, psychology, partisanship, language, culture, social media platform use, and the topic or subject matter of the disinformation narrative. This point is supported by the fact that organizations like Factchequeado and Conecta Arizona focus much more on serving a specific demographic rather than a specific physical location.

In the end, through these subgrants, we were able to support outstanding organizations while producing resources, holding events, and delivering services that would have been impossible for PEN America to do on its own, and that’s a big victory.

3. Instructional webinars on disinformation resilience

Between April 2024 and January 2025, PEN America developed and facilitated six disinformation resilience webinars. The decision to produce webinars—with a focus on training—came from the recognition that there’s a clear need that’s not being addressed for instructional resources designed for a general audience. While there is an active landscape of organizations producing webinars and instructional resources on disinformation resilience and media literacy, these other organizations, such as the National Association for Media Literacy Education, News Literacy Project, and Indivisible’s Truth Brigade, serve specialized audiences like educators or activists.

More broadly, there are many people who are not looking for media literacy training but want to learn how to effectively navigate our increasingly complex, fractured media information ecosystem. PEN America filled this gap.

Going beyond the familiar Media Literacy 101 content that’s readily available, we explored deeper topics related to how we consume news and information. And because we wanted our audience to learn media literacy concepts but also hear local perspectives, we used a hybrid format. Combining training content and panel discussions with experts—often local ones—we successfully married instructional content with lively discussion, bringing nuance and local flavor to media literacy training.

To determine the webinars’ impact, we used surveys to measure what audience members learned and their behavior change intentions—what participants said they would do differently as a result of what they learned.

By the Numbers

- 6 webinars

- 16 expert speakers, including journalists, academics, community leaders, content creators, and nonprofit leaders

- 517 live attendees, representing 407 unique audience members

- On YouTube, the webinar videos have a combined view count of over 1,600.

- On average, 89% of survey respondents indicated at least one key learning

- On average, 71% of survey respondents indicated at least one behavior change intention

- On average, 78% of survey respondents said they found both the training and discussion components helpful

Local Perspectives, National Reach

So… why are webinars a good fit for a capacity-building program focused on specific geographies?

Initially, PEN America’s community-level disinformation resilience work emphasized in-person workshops and panels as a way of forging bonds in our three focus cities. But our community contacts indicated that while participants felt the in-person programming was valuable, attendance was modest. Webinars emerged as a way to engage larger audiences.

But in addition to allowing for a larger audience, the format allowed several other advantages over in-person events offering disinformation resilience training:

- Accessibility. Miami, Dallas, and Phoenix are sprawling metropolitan areas. Contacts told us it can take an hour to drive from one side of their city to the other, creating a barrier to in-person attendance.

- Cross-regional learning. Webinars allow for learning not just within each city but among the three—and even nationally and internationally.

- Endurance. The ability to record the presentation allows the content to live on after the event. Recorded and posted to YouTube, the webinars took on a second life.

Of course, with an online format and a national audience, we needed to be mindful to focus on the needs and perspectives of our focus geographies. We did this by featuring guest speakers from Miami, Dallas, and Phoenix and highlighting case studies and viewpoints drawn from the regions. For our national audience, we framed the geographic focus by saying that the three cities could provide learning experiences for communities more broadly.

Admittedly, there are drawbacks to the webinar format, as compared to in-person events. Webinars make for a less personal experience, provide fewer opportunities for cross talk and relationship-building among participants, and limit opportunities to address region-specific issues. Our other activities, however—the grants and trusted messengers trainings—helped to fill in these gaps.

Content Overview

- “How Cognitive Biases Make Us Vulnerable to Disinformation—and What We Can Do About It” (Apr. 18, 2024)

- “How to Build Relationships with Journalists Covering Your Community” (June 20, 2024)

- “How Fact-Checking Works—and Why It Matters” (Aug. 15, 2024)

- “Election Countdown: Combating the Most Dangerous Disinformation Trends” (Oct. 2, 2024)

- “Understanding Election Disinformation: What Voters Need to Know” (Oct. 17, 2024)

- “How Influencers Are Changing Our Information Ecosystem” (Jan. 16, 2025)

Impact on Audiences

Survey data from webinar participants indicates a high degree of learning and behavioral change as a result of attending the webinars. Here are highlights:

Top learnings

- 100% of survey respondents said they’re more familiar with steps that fact-checking organizations take to make their fact-checks independent, trustworthy, and unbiased

- 90% of survey respondents said they better understand how they could effectively pitch a story or introduce themselves to a journalist

- 90% of survey respondents said they learned basic steps to investigate dubious election claims and debunk them against reliable information

Top behavior change intentions

- 89% of survey respondents said when consuming information, they will be more mindful about looking for signs of fact-checking, including evidence, attribution, and careful use of language

- 70% of survey respondents said if they reach out to a journalist, they will be more mindful of things like finding the right person and explaining why the issue matters

- 70% of survey respondents said if a friend or family member shares an election falsehood, they would be more likely to speak up about it

Looking Back on the Webinars

These webinars addressed key issues in a critical election season, and they also helped us to identify opportunities for further exploration or programming.

These include deeper dives into topics including effective prebunking and debunking strategies, media monitoring tools and techniques, best practices in civic communication, polarization and political violence, the impact of algorithms, and the effects of AI. An additional avenue could be to explore disinformation dynamics in the context of specific issues like public health, education, or immigration

In terms of format, this content could be repackaged into self-paced instructional courses, complete with exercises, message boards, and other interactive features to make for a more active asynchronous learning experience. It’s also easy to imagine the webinars being used as the basis for workshops in libraries, schools, and community centers.

Conclusion

From a workshop about news sources in a rural church in Seagoville, Texas, to a media literacy course on WhatsApp and a webinar about political influencers, PEN America’s DCE program touched the lives of hundreds of thousands of voters in Miami, Dallas–Fort Worth, Phoenix, and beyond during a presidential election year. Our programming—diverse as it was and with a sizable sample of partners and collaborators—demonstrated some of the myriad ways that organizations can build capacity against disinformation to uphold values of free expression and democratic discourse.

In a political climate that continues to be hostile to counter-disinformation work, efforts like these, focusing on information content consumers more than producers, hold potential in curbing the power of disinformation. While no single or even handful of entry points will be the magical cure to counter, programs that successfully empower community members to take on disinformation and that build resilience to disinformation among information consumers will be necessary and should be expanded, evaluated, and iterated on.

Closing

PEN America’s Disinformation and Community Engagement (DCE) program aspired to tackle a complex, global challenge with interventions focused on the regional and local levels. Through it, we reached many thousands of people, making a timely impact and providing a limited but clearly positive set of data in terms of impact and directions worth pursuing.

Regrettably, disinformation isn’t going away and, in fact, has become a go-to strategy for growing and maintaining power in today’s political climate. These times call for robust programming to help develop capacity against false and misleading information. Efforts that demonstrate how combating disinformation is consistent with supporting free expression are crucial.

In addition, our efforts have also shown that many different kinds of activities can achieve impact. It is our hope that national, state-based, and local organizations are able to take inspiration from this work, build on it, and cultivate resilience among their own constituencies.

Acknowledgements

This report was written by Henry Hicks, Manager of U.S. Free Expression Programs, and Kurt Sampsel, Senior Program Manager on the Disinformation and Community Engagement team. It was reviewed and edited by Tim Richardson, Director of the Journalism and Disinformation Program; Jonathan Friedman, Sy Syms Managing Director of U.S. Free Expression Programs; and Eileen Hershenov, Deputy CEO and Chief Legal Officer.

We are deeply grateful to our colleagues and external consultants who contributed to this work, along with external consultants Michelle Beaver, Martina Van Norden, and Antonio Camejo.

We also extend our sincere thanks to the reporters, staff, and leadership at Factchequeado, Conecta Arizona, and the Texas Tribune for their invaluable partnership; in addition to community partners such as Dallas Public Library, Dallas Free Press, Dallas Documenters, Tarrant4Change, LOOKOUT, United Teachers of Dade, Boys Hope Girls Hope, and Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication. This report also benefited from insights shared by numerous experts, both internally with our staff and publicly through our webinar series.

PEN America is very grateful for the generous support of the Quadrivium Foundation, which made this report possible.

Finally, we recognize and commend the many citizens of Dallas, Phoenix, and Miami who are on the front lines of the fight against disinformation in their communities. Your efforts to raise awareness and defend the truth inspire us, and we are proud to stand with you.

Learn More

-

Exploring How to Build Community-Level Resilience Against Disinformation

Disinformation, and the ability to counter it, is intertwined with factors including trust, polarization, economic conflict, social isolation, prejudice, and mental health.

-

Speech in the Machine

Introduction The rapidly expanding era of artificial intelligence (AI) is ushering in both exciting possibilities and precarious unknowns. AI technologies are already powerful curators of information and arbiters of online content, and often amplifiers of disinformation. As AI technology—particularly generative AI technology—evolves, its potential impact on human rights and the fundamental right to free expression

-

Building Resilience

Introduction Disinformation as a Free Expression Issue People need reliable information to participate fully in the democratic process. Particularly, they need it to choose their next elected representatives, assess policy and policy proposals both locally and nationally, and engage in civic discourse. In recent years, however, the political information landscape has become increasingly fraught for

-

Impact Report

PEN America & Stanford Social Media Lab Preview The goal of PEN America’s media literacy work has always been to better equip those we reach with the skills and knowledge to assess the credibility of information and to make informed decisions about what news sources to trust. Since launching our Knowing the News media literacy program in

-

Noticias duras

Click here to read this report in English. Hallazgos sobre cómo la desinformación trastorna el ejercicio del periodismo según una encuesta nacional realizada por PEN America a más de 1.000 periodistas y editores Hallazgos clave: Sin embargo, a pesar de estos altos niveles de inquietud y claro impacto en su ejercicio profesional, la mayoría de

-

Hard News

Haga clic aquí para leer este informe en Español. PEN America’s nationwide survey of more than 1,000 reporters and editors on how disinformation is disrupting the practice of journalism Key findings: Yet despite these high levels of concern and clear impact on their practices, most journalists responding said they did not feel they had the

-

![Text on a cloudy background reads: [Truth on the Ballot - Fraudulent News, the Midterm Elections, and Prospects for 2020] enclosed in bold red brackets.](https://cdn.pen.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/22191626/truth-on-the-ballot-report_featured-image-1.png)

Truth on the Ballot

With fraudulent news and online disinformation distorting public discourse, eroding faith in journalism, and skewing voting decisions, Truth on the Ballot offers a stark warning about the normalization of fraudulent news and disinformation as campaign tactics, sounding an alarm that such unsavory methods are becoming part of the toolbox of hotly contested modern campaigns. Micro-targeting capabilities have

-

Faking News

Warning that the spread of “fake news” is reaching a crisis point, Faking News: Fraudulent News and the Fight for Truth evaluates the array of strategies that Facebook, Google, Twitter, newsrooms, and civil society are undertaking to address the problem, stressing solutions that empower news consumers while vigilantly avoiding new infringements on free speech. Faking News rates the range

-

Trump the Truth

PEN America’s new report Trump the Truth: Free Expression in the President’s First 100 Days clocks more than 70 separate instances where President Trump or senior Administration officials have taken potshots at the press, including Presidential tweets decrying “fake news,” restrictions on media access, intimations that the press has “their reasons” for not reporting terror attacks, and