The PEN World series showcases the important work of the more than 140 centers that form PEN International. Each PEN center sets its own priorities, but they are united by their commitment to advocate for imperiled writers, promote literature from all cultures and in all languages, and advance the right of every individual to speak freely.

In this series, PEN America offers a window into the literary accomplishments and free expression challenges of their respective countries. Today, we spotlight PEN Haiti by republishing an article by Ervin Dyer, originally published in the New Pittsburgh Courier.

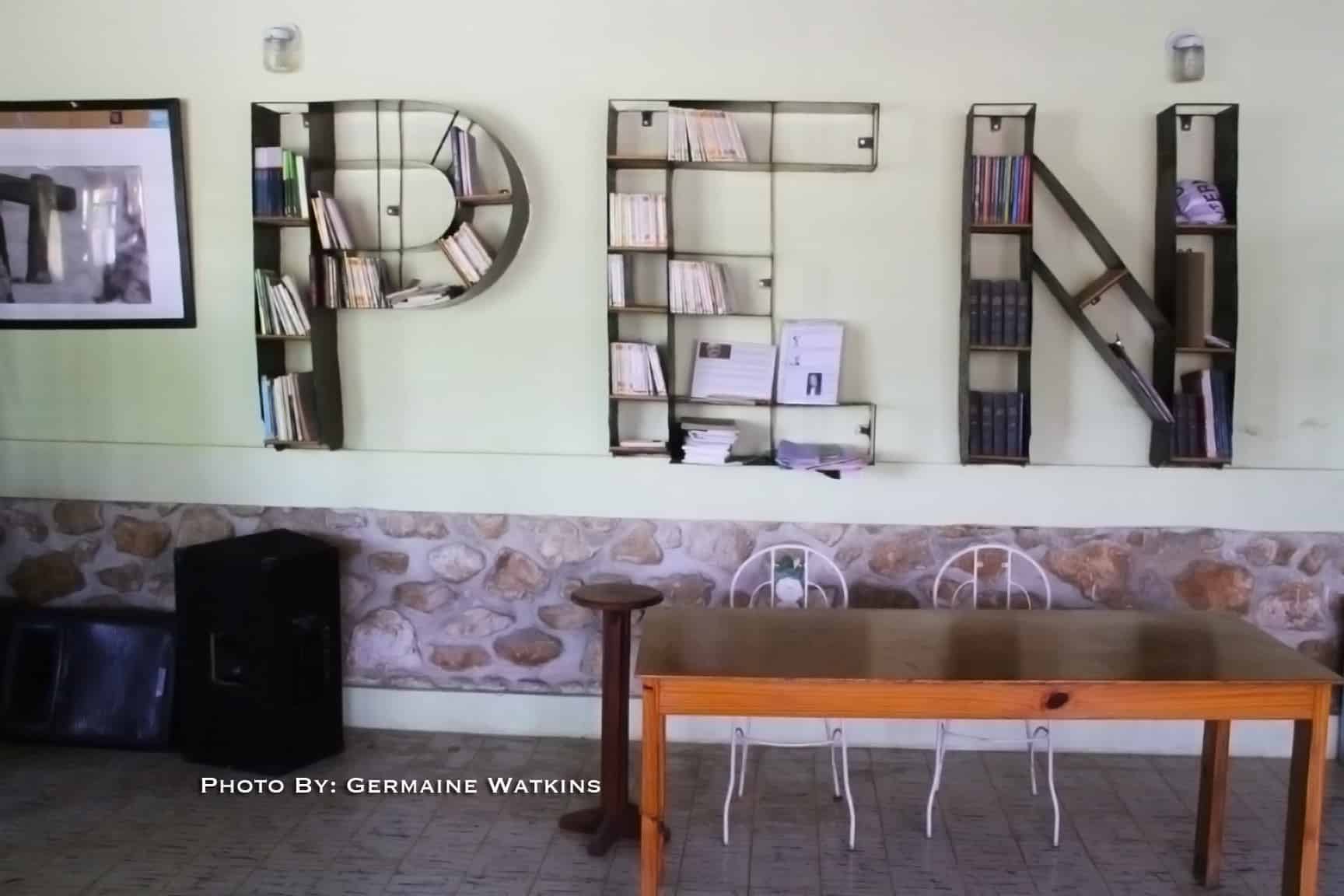

In the hills of Haiti, about 40 minutes from the capital of Port-au-Prince, under the lavender bougainvillea and the fiery orange flamboyant trees, something even more beautiful happens behind the gate of the Maison Georges Anglade.

The house, in the Thomassin community, is a sanctuary for Haiti writers.

It is a place where poets, novelists, and essayists come to complete their projects and engage in the practice of free expression. It is a place that takes care of the writer. A small fee is charged, and the writer gets food and lodging. For those who don’t want to reside here, writers can come to use the library or the computer lab, where they sit in the shade of the bougainvillea and write.

It is a creative space. During the day, it is a space that welcomes all types of writers. There are those who are educated, those who live in tent cities, and those who believe they were born to write. It is also a space that provides workshops to students and local residents, pushing the realization that all can develop the capacity to be a writer. Most nights there are readings and music.

PEN Haiti began in 2002 and is part of PEN International, a global organization that promotes freedom of expression as a way to advance human rights. The house was acquired in 2012 and named for a Haitian scholar and ethnographer.

Since the residence has opened, more than 400 young writers have come through. Some have had the opportunity to work and engage with famous author and poet-playwright Frankétienne and poet-novelist Lyonel Trouillot, both whom write in French and Haitian Creole, and with Emmelie Prophète, a writer and diplomat who represents broadening outreach to women writers in Haiti.

PEN Haiti is an important space. In Haiti, only about 60 percent of the population can read or write, and only about 20 percent progress to school beyond the eighth grade.

“To fight against those kinds of statistics, the work we do encourages literacy,” said Evans Momparnousse, a director of PEN Haiti, who spoke through an interpreter and recently gave American visitors a tour of his home. “We see what we do as a way to use writing as a way to preserve our culture, but also because it values freedom of speech and expression. We believe that supporting writers helps to bolster freedom of speech.”

To expand its mission, PEN Haiti is now providing yearly reading and writing seminars in rural areas, such as Jacmel, Gonaïves, and Saint-Marc. “We want to reach the young people,” said Momparnousse, “giving them a way to use their voices to debate political, social, and economic issues in Haiti.”

One way to do this, said PEN Haiti, is to encourage writing in Creole, the language that is a mix of African, French, and the indigenous tongue of the native people of Haiti. It is spoken by seven million people and is the language of the everyday man and woman in Haiti. Though French is the formal language in Haiti, many Haitians speak another language—English, Spanish, and more—as way to engage visitors, but “we support writing in the local tongue; to give value to it,” said Momparnousse. “Using it to create novels and poems is a way to preserve the language, too.”

In fact, PEN Haiti has instituted what it calls the Creole Academy to promote the writing and sharing of culture among the people who use the local language, advocating its use as kind of confrontation with French, the language inherited from colonial power and spoken by the elite minority. “It’s a way,” said Momparnousse, “to tell the local people that their language and culture matters.”

The poet and writer Shelo Francois was recently at PEN Haiti in Thomassin on a three-week residency to finish a book of poems that addresses environmental justice and cultural identification.

He said he’s been a writer since he was born. One of his influences and favorite writers is the noted Haitian author Jacques Roumain, who wrote of peasant life and culture, and was friends with American poet Langston Hughes.

But growing up in Port-au-Prince, Francois was deeply influenced by urban culture and the diaspora arts that penetrated city life. He was drawn to slam and spoken-word poetry and rap music from France. He would perform in school, and a teacher told him he had potential to be a writer.

He studied and earned a license in clinical psychology, but the love of writing and being creative never left his soul. Today, in addition to writing, Francois makes a living holding writing workshops in Kenscoff, a small city in the hills about 40 miles from Port-au- Prince.

Francois said PEN Haiti is an important project because it provides writers with connections, a network of support, a peaceful environment to write, and a creative space to be inspired.

“It’s also important for its outreach and nurturing of young writing,” he said, filling a hole left by the government, which too often ignores writers until they find acclaim.

Young writers today, said Francois, see writing as form of protest, a way to push for equality, embrace the intellectual canon, and highlight social and cultural issues such as the influence of voodoo on society.

“We are grateful,” he said, “that a place like PEN Haiti opens the doors to help make this happen.”