On Prison Art and Music

Joseph Wilson and I sit at an antique Casio keyboard in the Sing Sing Correctional Facility music room. He’s hunched over the keys, concentrating deeply while playing a new song he’s composed. Somewhere in the middle he strikes a chord that feels both horribly wrong and deliciously sharp. The dissonant harmony breaks my expectations of where I thought the piece would go, triggering an instant, visceral emotional response. I told him it was probably a mistake. He told me confidently he intended it to sound that way.

It’s been years since Wilson and I have shared a seat at a keyboard. Since those early musical works I witnessed him develop, Joseph Wilson has gone on to become a respected composer, and his operas have been sung by Grammy Award-winning classical performers, such as leading soprano Joyce DiDonato. His latest opera, 9131: A Sing Sing Story, is a dramatic rendering of the parole process, and was recently staged at Carnegie Hall. And while world-renowned performers breathed life into his musical creation in the heart of New York City, Wilson continued to do time upstate.

When I listen to music produced in prison, there’s a set of layers to how I experience the work. I think of the hours of practice, the search for material to study, and the tenacity required for adult learners of music. In the case of ensemble work, I think of the challenging frictions inherent to groups and the remarkable success a chorus can struggle to achieve. Mostly, though, I think of the performer as a full person, with dreams and desires, worthy of connection, support, and freedom.

My hope for any listener is that they interrogate themselves a bit. When they feel boredom, or cynicism, or perhaps dismissive of the craft, I hope they imagine themselves at the heart of the creative process. I hope they envision putting their selfhood on the line as the ultimate expression of vulnerability. I hope they imagine what it takes to share joy or passion-for-life that might make them a target, but also provides healing. When a community shares the work of incarcerated artists on podcasts, in print, and on stages, foremost in my mind is this alchemy and exchange. The incarcerated artist asks the listener if the listener deserves forgiveness.

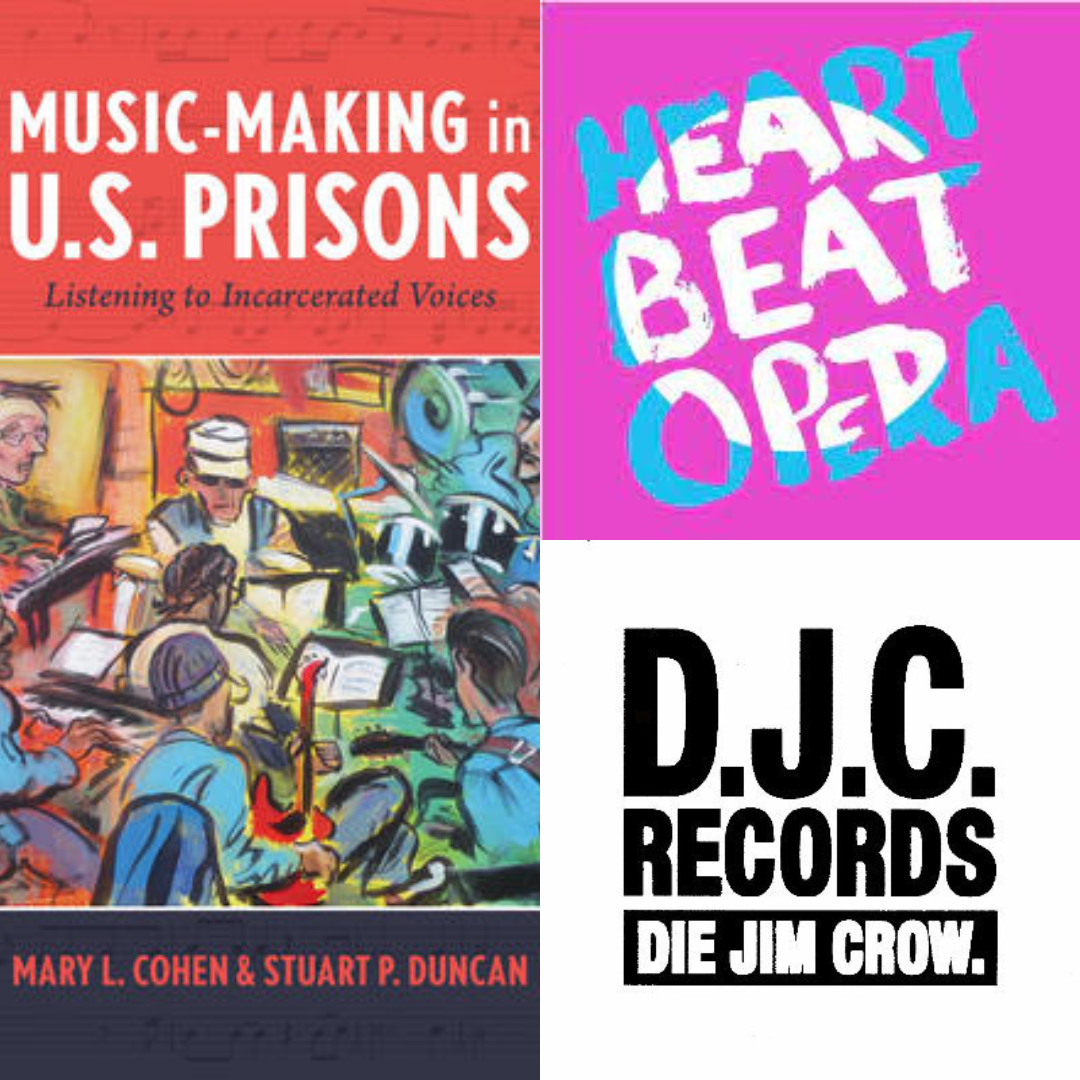

Highlighted here are three projects whose work epitomizes this form of artistic exchange. Heartbeat Opera’s incredible production of Beethoven’s Fidelio manages the feat of bringing to life a 200-year-old opera and interweaving incredible choruses of incarcerated singers from across the country into virtual streams. My friends at Die Jim Crow Records have been on the edge of what’s possible by centering the artistry of musicians in prison for years and they’re still pushing boundaries. Finally we’ll look at some surprising historical research, analysis, and field notes from practitioners teaching music in prison today in Music-Making in U.S. Prisons: Listening to Incarcerated Voices.

In spite of the success of these projects and initiatives, there are many remaining obstacles to the creative self-determination of incarcerated artists. Censorship, restrictions, negative public sentiment, and lack of state support prevent these kinds of programming initiatives from becoming widespread. If you are interested in supporting arts programs like this, check out the programs in your area on the Justice Arts Coalition Program Directory.

Heartbeat Opera’s Fidelio

Let’s admit it, not everyone is a fan of opera. In fact, it can feel downright inaccessible to some. For fans of cultural bridges, Heartbeat Opera’s production of Fidelio is a guidestar. One hundred incarcerated singers with 70 volunteers in the Oakdale Community Choir, KUJI Men’s Chorus, UBUNTU Men’s Chorus, HOPE Thru Harmony Women’s Choir, East Hill Singers, and Voices of Hope lend their voices in this retelling of a timeless story that Heartbeat Opera’s creative team reinvisioned as a critique of current carceral practices in the United States. The logistical triumph is worth it alone, but coupled with the gut wrenching melodies and stellar performances, Heartbeat Opera has paved the way for a new way of approaching collaboration beyond the walls. Recently, Ethan Heard and Marcus Scott spoke with PEN America’s Works of Justice podcast about their process of developing the production with incarcerated vocalists.

Die Jim Crow Records

I’ve known Die Jim Crow founder Fury Young since 2018 when he attended PEN America’s annual Break Out: Celebrating the PEN Prison Writing Awards. Back then, we talked about the indomitable power of music in prison. In the years since, Die Jim Crow has gone on to release several albums, provide instruments to hundreds of incarcerated musicians, and lead a movement that forefronts incarcerated and formerly incarcerated artists. Music from Die Jim Crow’s artists also graces PEN America’s Works of Justice podcast, giving us an edgy vibe to complement the critical conversations we hold with key figures confronting the justice system. You can read more about Die Jim Crow’s evolution in an exclusive interview with former PEN America intern Tomás Miriti Pacheco and label Co-Executive Directors BL Shirelle and Fury Young.

Music-Making in U.S. Prisons: Listening to Incarcerated Voices

Over the last 75 years, there has been a radical decrease in musical programmatic and artistic opportunities in prisons throughout the United States. But, that doesn’t mean there aren’t organizations and individuals working to celebrate the musicianship of incarcerated artists. In Music-Making in U.S. Prisons: Listening to Incarcerated Voices (Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2022) authors Mary L. Cohen and Stuart P. Duncan put historical research in context with current prison arts programming efforts. In short, they demonstrate how music programming in prisons is beneficial both for the individual musicians and communities in and out of prison. Even more important, they are honest about the pitfalls of harmful savior tropes.

Robbie Pollock is the Prison and Justice Writing Program Manager at PEN America. A multidisciplinary teaching artist with Music On the Inside (MOTI), Pollock is an alumni and facilitator for several arts-in-corrections programs, including Carnegie Hall’s Musical Connections, Rehabilitation Through the Arts, Musicambia, and Road Recovery.