This Q&A is part of a series that will include interviews with journalists and experts who regularly handle disinformation. The interviews will appear regularly through the election and beyond to highlight best practices, insights, case studies and tips. Our goal is to provide a resource to assist reporters and community members through the news events of 2024.

Nina Jankowicz isn’t a journalist, but the author and counter-disinformation expert has a lot to say about how the media can handle disinformation campaigns ahead of the 2024 election, as well as the torrent of abuse that can accompany reporting on false information. Jankowicz has testified before Congress and advised governments, written two books on disinformation and online abuse, and led research on the effects of disinformation on women, minorities and free expression. Her work has put her in the crossfire of online harassment campaigns while speaking out on how the U.S. government and Western media can battle threats posed by disinformation.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

For journalists navigating or covering disinformation, what tactics have you noticed that work? What do you think is less effective for journalists encountering disinformation?

I think one of the most important things is the sandwich rule – to make sure that you are sandwiching a lie between the pieces of truth, just because, clearly, if you’re not repeating the truth multiple times, then often what people remember is the lie. But also – I guess this falls under both a practice and things I’ve seen some journalists fall victim to, which is trying to soften language around disinformation. We need to call it what it is. There’s a coordinated effort right now to undermine the entire disinformation research sphere, so if we’re not calling a lie “a lie” or calling it “disinformation” when it is disinformation, and we’re just calling it “falsehoods” or something like that, then we’re really cheapening the broader attempt to undermine that coordinated behavior. Those would be the two things that come to mind broadly.

A huge issue for journalists when it comes to combating disinformation is that trust in the news media is at an all-time low. How do you think journalists can start rebuilding trust when they’re covering disinformation, which only encourages distrust?

One of the most important things in terms of building trust is pulling back the curtain into how reporting gets done. I think the more that journalists can take readers or viewers on the journey with them and show how things were done, the better equipped viewers are to understand the journalistic process. They understand that it’s not just that they’re being hit with lies, or that there’s somebody who’s got a political ax to grind, but that journalists are going through a process and there is a reason that this story was chosen. I think that’s all really important.

To pivot to something more broad: How do you think the threat of disinformation has evolved since the 2016 and 2020 elections, and how do you think it will impact 2024? What is your biggest fear about the current state of disinformation and politics?

In 2016, obviously, this phenomenon was a lot less normalized in our body politic. It was something that a lot of people, perhaps incorrectly, viewed as only Russia being involved in. Obviously, there’s always been domestic disinformation, and foreign disinformation is only as successful as our vulnerabilities at home. I think there was a lot of focus on Russia, and as a Russianist, I don’t think that was totally misplaced, but it was perhaps a little overblown. And also, the ways that Russia was interfering are very different from what we see nowadays. Back then, it was a lot of coordinated, inauthentic behavior in troll armies and using bots. Now, it’s become more difficult for any entity to pull off that sort of behavior, so we have different approaches that continue to undermine trust in the news media.

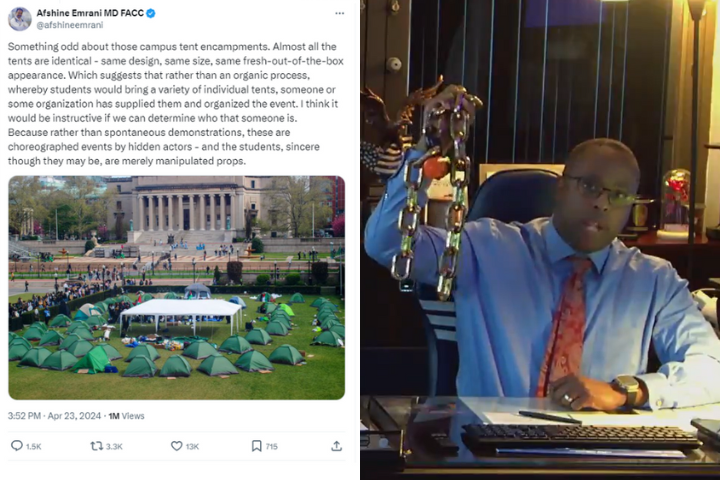

You’ve probably seen the reporting about the guy who is an American citizen who fled to Russia and now is using generative AI to populate fake news sites – and when I say fake news sites, I mean, they are sites posing as local news outlets. That’s how things have really changed. It’s not about, can you spot a bot? It’s, are you consuming things in a deliberate enough way that you’re not going to get duped by something that looks credibly like a local news entity. That’s how things have changed, going from those very broad astroturfing operations to things that are powered by AI targeting vulnerable populations, targeting the mistrust in our society.

Given the distrust, given the normalization of disinformation used by political candidates, given the attacks on the disinformation research sphere, I’m just worried there aren’t enough eyes on the ball as we head for November. I run a nonprofit in this space. There are a lot of nonprofits that are focusing away from disinformation right now because of how difficult it’s become to get funding and to stay out of political battles related to this stuff. I’m just worried that we are not prepared. And then, when you add the fact that the government has also, until recently, been a little bit hamstrung by ongoing litigation in order to respond and recognize disinformation, things get complicated really quickly. I’m worried we don’t have enough eyes on the ball and worried we’re not ready.

Going back to those AI-generated fake news websites you mentioned, some experts think the threat of deepfakes and generative AI is overblown. Do you think that’s true?

Obviously there has been a lot of hubbub about AI. But I think we are more likely to see large language models (machine learning models that can comprehend and generate human language text) deployed this election than super convincing deepfake videos, audio or images. I think people are pretty well primed to recognize that that stuff is out there and that they should be careful with it, whereas, when you’re consuming text, unless the individual who’s using the LLM has, you know, copied and pasted a prompt for the LLM into the final copy that they’re using, there’s not really a way for you to know that it was created with an LLM.

When I look at our foreign adversaries, many of the reasons we were able to identify those operations was because they had linguistic peculiarities that were specific to a non-English speaker. That’s not going to happen anymore. And not only is that not going to happen, but now, adversaries can create that text at scale, targeted to the most vulnerable communities or to target communities that are going to think or act a certain way or receive that information a certain way. That’s what worries me the most. Also, to those folks who are naysayers about all this, I would also say: It’s only July, and if I had my hands on an explosive deepfake or the ability to make one that was really convincing and the mechanism to spread that very quickly, I would not be doing it in July. So I would say the jury is out. I agree that the concerns about AI are somewhat overblown, but I do think they need to be accounted for as we prepare for what’s to come.

I know that you’ve faced a lot of harassment and online abuse, and there was even a deepfake of you made because of your research and writing on disinformation. How did you handle that? What advice would you have for journalists who are facing that kind of online abuse or who are scared to cover disinformation because it makes them vulnerable to those kinds of attacks?

This is something that, unfortunately, has become a reality. I think the people who are covering disinfo, especially if they are women or members of other kinds of intersectional identities or marginalized communities, are more likely to receive that sort of stuff. First, I would say PEN America has really great resources for a journalist; definitely consult those. And make sure that your IP address (the numbers assigned to internet-connected devices) and operational security are as locked down as possible. When I dealt with the worst of my harassment, the private security consultant that I hired told me that if I hadn’t gone through everything I had gone through to make sure my accounts were locked down – that I had two-factor (authentication) on everything, that I had DeleteMe or a similar service scrubbing my personal information from the web – things would have been much worse, which is kind of scary to think about. And only because I was an expert in cybersafety and online harassment had I done that going into government. I would say it can be kind of scary to think about, but I describe it as “set it and forget it.” Once you do it, you set up your system, you set up your password manager, you’ve got your authenticator that is working for you, you don’t have to think about it very much after that. And it’s so, so important.

Other than that, there’s always going to be some degree of criticism. The sort of stuff that, particularly, the women in the counter-disinformation sphere have dealt with is beyond the pale. I mean, as you said, I had a nonconsensual deepfake porn, actually several of them, made of me. That wasn’t the worst thing I dealt with. The worst things were cyberstalkers and frivolous lawsuits and direct threats against me and my family, including when I was at the very end of my pregnancy with my now-toddler. It’s really difficult. I think making sure that you’re proactively figuring out support systems for yourself is hugely important.

Luckily, a lot of journalists – this sounds weird to say luckily – but a lot of journalists have gone through this stuff, so I think compared to other fields, like academia, for instance, or even government, you’re more likely to find colleagues who are going to be able to help you through that stuff in a better way than some other fields. But seeking that support is so, so important, because it’s a really isolating thing to go through. And bringing it up with your bosses proactively is really important. I know more newsrooms are starting to invest in efforts to think proactively about online abuse and harassment. But particularly for this beat, I think it is really incumbent on everybody to make sure that safety is being prioritized. And if you feel like your newsroom is not doing that, bring it up with your boss as soon as possible and make sure it’s on their radar so that it’s not like they’re a deer in the headlights when the worst does happen.

I’m sorry that happened to you, and that’s very good advice. To try to end things on a slightly more positive note: As disinformation continues to spread and generative AI gets more sophisticated and things seem more bleak, what – if anything – keeps you hopeful about the state of disinformation, coverage and where the media is going?

I mean, if I weren’t hopeful, I wouldn’t be doing this work. I’d be on an island somewhere teaching yoga – and I haven’t done that yet, but who knows, after November maybe I will.

I think people still want to have good information at their fingertips. I do believe that. And I think if we give them the skills they need to navigate today’s information environment, it only takes a little bit of guidance so they can do that better. Even with things like generative AI, just saying to them that this stuff is out there and that, if something that you’re looking at or listening to seems a little bit weird, waiting until it’s been forensically confirmed – particularly in big, hot-button events or crises – helps people more deliberately engage with our information environment.

I did see a paper recently that was really exciting that talked about inoculating people against emotional manipulation, which is one of the big tactics that disinformation uses. The study showed that if people were warned or educated about emotional manipulation before trying to determine if news articles were true or false, they were more able to delineate truth from what’s false. That’s just such a good and encouraging result, right? It’s just a little heuristic, knowing that if you feel yourself getting emotional, then you might be manipulated. That’s huge. That is something that gives me hope, and it’s just a matter of systematizing those approaches to the public and getting them to people in a way that is nonpartisan, that is accessible and at the same time, that is building back trust in the institutions that have been so affected by this stuff over the past couple of years.

Jankowicz recently appeared on NPR’s “Morning Edition” to discuss gendered disinformation and online abuse aimed at Vice President Harris after President Biden endorsed her for the top of the Democratic ticket. Jankowicz cited a 2020 study she led in revealing several disinformation narratives that have resurfaced in recent days: misogynistic false claims that she “slept her way to the top”; transphobic false claims — sprung from a QAnon conspiracy theory — that she is “secretly a man”; and racist false claims that she is not eligible to be president because of her immigrant parents. Jankowicz described these disinformation narratives as an attempt to undermine Harris because of her gender and racial identity.

Jankowicz’s work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New York Times and BuzzFeed News, among other publications. She is the author of “How to Lose the Information War” and “How to Be a Woman Online,” and is co-founder and chief executive of the nonprofit American Sunlight Project. Jankowicz led the Department of Homeland Security’s short-lived Disinformation Governance Board and was a fellow at the Washington-based think tank Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.