This Q&A is part of a series of interviews with journalists and experts who regularly handle disinformation. The interviews will appear regularly through the election and beyond to highlight best practices, insights, case studies and tips. Our goal is to provide a resource to assist reporters and community members through the news events of 2024.

Politico national security reporter Joseph Gedeon has covered a range of topics across the world, from Dubai to Montreal to Washington. His time covering politics and misinformation at The Associated Press during the 2018 midterm elections offered insight into how disinformation campaigns have affected U.S. elections in recent years as technology and manipulation tactics have grown more sophisticated. He is the author of the Morning Cybersecurity newsletter at Politico.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

You covered misinformation for The Associated Press and are now covering national security for Politico. How are you seeing misinformation and disinformation campaigns play out in your work? Are there new tactics you’re seeing?

We’ve definitely been seeing new tactics. I was at the AP in 2018 and 2019, and that was during a midterm year. What we were seeing then was a lot of misinformation being spread that looks amateurish compared to what we’re seeing now. Back then, we were tracking how viral they were getting to see what was sticking, and they were based on big events. And of course, there were state actors involved back then, notably Russia. But what we’re seeing now is a massive storm of disinformation tactics and influence operations. We know that Russia and China are both investing over $1 billion in their disinformation networks and they’re playing out massively, and while it’s still focused around big events, it’s now also a constant barrage. It’s sort of like the game of two truths and a lie, and it gets blended together to cause disarray.

What we were talking about back in 2018 were bot farms, and now the bot farms are very heavily AI. There are AI messages in tweets, in comments on YouTube, on Facebook, on Instagram. You see it on TikTok, as well, basically every single social media platform. AI makes things so much easier, and you’re actually seeing this play out in real life. But essentially, what we’re seeing is a lot of these state actors – Russia, China, Iran, sometimes North Korea, we’ve even seen Israel in the last year – do these disinformation campaigns to push their government’s propaganda message.

You’ve spent a lot of time writing about the war in Gaza. What kind of online disinformation campaigns are coming out of the war? Are you seeing any lead to offline violence or conflict?

There are a massive amount of disinformation campaigns coming out of the war to startling effect, from both Iran-linked accounts and other pro-Palestinian factions, and the actual Israeli government and other pro-Israel actors. It’s hard to measure what causes real-life violence. It’s information overload, and not just for people who are just learning about Israel and Palestine. There was the 6-year-old Palestinian American boy in Chicago in October who was stabbed to death over two dozen times by his family’s landlord, with court documents saying the accused was influenced by conservative radio shows, which could very well have included disinformation.

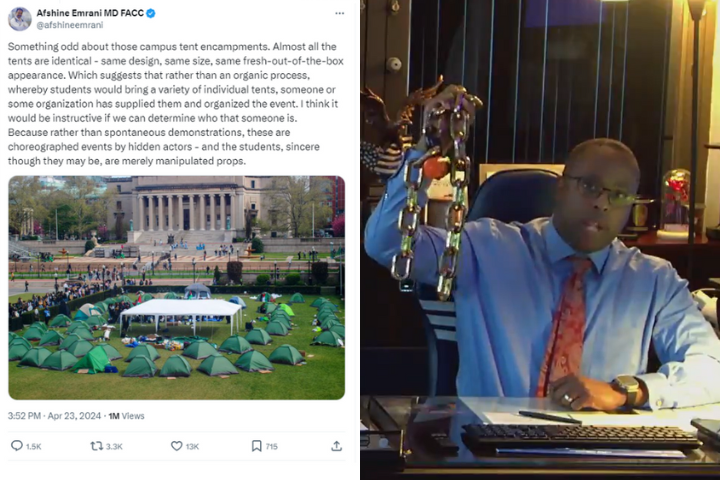

We’ve seen pro-Hamas accounts misrepresent footage by using clips from the Syrian civil war, and we’ve seen accounts linked to the Israeli government post doctored footage of humanitarian aid to Gaza and impersonating nurses or journalists in Gaza to say that Hamas had taken over hospitals, or that Hamas had struck a hospital. And here in the United States, that includes conspiracy theories being spread on college campuses during the student protests and an even bigger disinformation campaign to delegitimize those same student protests to get them shut down.

One big campaign that we had exclusive reporting on was Israel’s government being linked to a disinformation campaign that targeted over 120 American members of Congress and senators on social media by using hundreds of fake profiles to coordinate thousands of comments per week backing Israeli’s military actions and dismissing claims of human rights abuses. It’s hard to know if this had any real-life impact, but I scroll through comments to get an idea on what people are saying on any particular comment and it’s disquieting to think that government propaganda could be meshed in with that.

That’s not to mention atrocity denial, which disinformation experts have seen a massive uptick in since the war began – people claiming what they are watching online is being doctored or that victims are crisis actors faking injuries and death.

Biden stepping down and Kamala Harris rising as the Democratic nominee has created a flood of racist, sexist disinformation campaigns. How do you think journalists can report on this without amplifying the claims?

It’s definitely a tough task for journalists. Sometimes even when trying to talk about conspiracy theories or racist and sexist disinformation campaigns as ridiculous, or by trying to mock how goofy it is, you can unintentionally expose them to people who hadn’t heard it before or make it more familiar in people’s minds, which helps its perceived credibility.

I’d say the goal is to just be as clear as possible, and you could even consider Taiwan’s approach this past year. Taiwan held its elections in January, and it’s a place China has serious geopolitical priorities in. The Chinese government flooded the Taiwanese social media space with disinformation campaigns, and both the government and journalists in Taiwan worked together to soften the impact. What they did was focus on the facts by debunking false claims without repeating them verbatim, and by providing context through broader patterns and motivations behind disinformation campaigns.

They also interestingly used data visualization to illustrate the scope and nature of those campaigns and how they spread, and discussed the underlying impact, which for them had been that their democracy was being undermined. They also showed readers how to use critical thinking to evaluate something that could potentially be disinformation.

You wrote about the assassination attempt on former president Trump. A lot of mis- and disinformation started spreading in the wake of the attack. How can journalists best navigate the flood of conspiracy theories after massive breaking news events like this?

The best thing you can do is to not get ahead of yourself. Journalists, by nature, are inquisitive and skeptical, so keep that up when it comes to verifying information online. You can do a reverse-image search on Google for pictures, you can search the words you heard in a video or post to see where they originated and if it’s based on a credible source. There are a ton of AI voice filters all over the place now. We’ve, of course, seen Elon Musk sharing some Kamala Harris ones recently on X to his millions of followers. There are some Joe Rogan AI videos that are being used on social media, too, so it’s going to get even more rough out there.

There’s been a lot of concern about the effect disinformation, deep fakes and generative AI might have on the election. Do you think those concerns are valid or overblown, and why?

The answer is it’s both legit and overblown. We’ve already seen instances of disinformation campaigns affecting elections. Just think about what happened in Taiwan earlier. AI can make deep fakes and disinformation highly personalized and targeted, and aimed at key demographics or regions on social media – not to mention the scale they can be produced at, which may mean they aren’t fact-checked fast enough.

There’s an argument to be made that once someone’s read it or viewed it once, fact-checking may be too late. But there’s a growing awareness about the existence of deep fakes and AI-generated content. People are a lot more tech-savvy and their media literacy has gone way up over the last few years. Tech companies are increasingly focused on the issue, and so is the government in coming up with AI-election-focused regulations. For example, a couple weeks after President Biden was spoofed in an AI robocall saying the primary for New Hampshire was on a different day, the FCC cited a decades-old law to make it illegal.

A huge issue for journalists when it comes to combating disinformation is that trust in the news media is at an all-time low. How can journalists start rebuilding trust when they’re covering disinformation, which encourages distrust?

Some strategies journalists could take is to be as transparent as possible. Don’t expose private sources, but explain how information was verified and why certain experts were chosen. Being open about your reporting methods could help readers understand what goes into making a story. And always try to give some context. Demystifying the process could combat misconceptions on how journalism works.

I think local news media have a better reputation than national media outlets in their own communities when it comes to trust, and that’s something that should be embraced.

And maybe this goes without saying, but don’t make the disinformation-spreaders feel like fools. Try to engage respectfully. Sometimes they have a point, and can spark an interesting story idea or perspective that you might have missed. If you can have Q&A sessions with readers, that could go a long way, too. And admit and correct mistakes when they happen. That shows a commitment to accuracy.

Before Politico, Gedeon worked at WNYC/Gothamist covering criminal justice in New York City and New Jersey, and at The Associated Press, where he covered politics, misinformation, and race and ethnicity. He speaks English, Arabic and French.