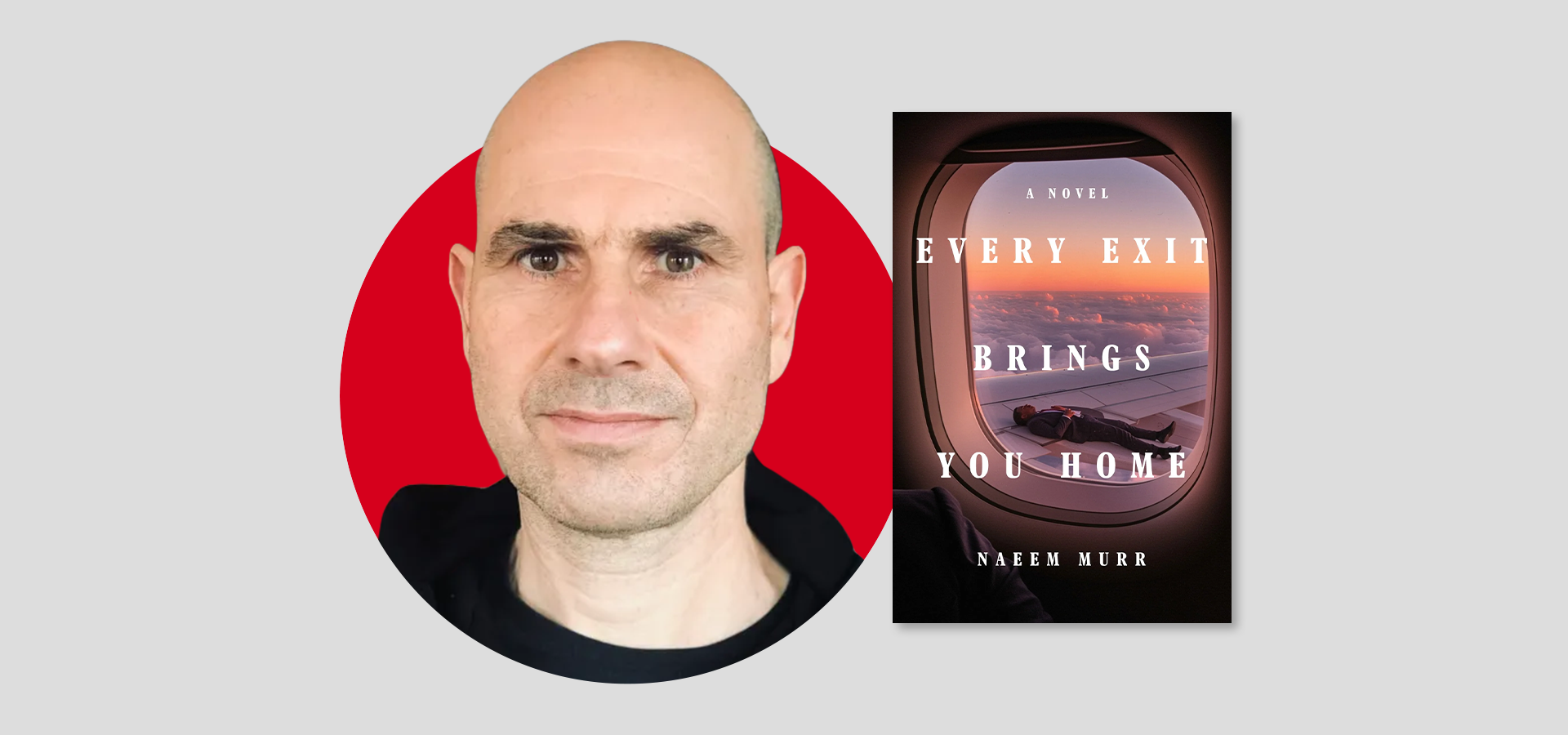

Naeem Murr | The PEN Ten Interview

Naeem Murr’s fourth book, Every Exit Brings You Home (W. W. Norton & Company, 2026) follows Jamal “Jack” Shaban, a Gazan immigrant who serves as the president of his condo association in Chicago. But he’s no simple protagonist — as the novel progresses, it becomes clear that Jack is a compassionate leader yet a chronic liar, a devoted husband but an undeniable adulterer. The story deftly weaves present and past, shifting between Gaza in the 1980s and Chicago in the 2000s, as Jack seeks to understand his own identity and support his struggling community.

In this PEN Ten interview, Mira Seyal, manager for foundation relations and grants, speaks with Murr about Jack’s struggle to chart a path forward in America, given the hold his traumatic past has on him. They also discuss the meaning of the novel’s paradoxical title and literature’s capacity to offer new perspectives on love, belonging, and sacrifice (Bookshop; Barnes & Noble).

Every Exit Brings You Home is your fourth book with your last one, The Perfect Man, published over 10 years ago. How did your approach to writing — and your sense of what this story needed — change in the years leading up to this novel?

Thomas Mann once said that a writer is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people. So much of the writing process for me is subconscious and out of my control. Though my work, of course, refracts my life, I don’t write autobiographical fiction. I want to get beneath what I consciously know to what I don’t know I know by aiming for a “Goldilocks” novel — neither too close nor too far from my life. All my books have been triggered by something I’ve seen, heard, or otherwise encountered: The Boy by a true story I was told about a foster child who destroyed a family; The Genius of the Sea by a newspaper article about a welfare cheat claiming disability; The Perfect Man by an abandoned town in the eerie landscape of the Missouri floodplains; and Every Exit Brings You Home by the sight of a couple sitting in an old Chevy Impala hitched to a U-Haul outside my apartment building. These triggers didn’t create the novels; they brought stories that had been gestating in me for years to the crisis of birth. The only thing I have control over in this process is my facility with the craft required to at least approximate that elusive “perfect” novel trying to find its way into the world.

This recent novel, the first that draws from my Palestinian heritage, was a long time coming because it took all those years to conceive and gestate a story and characters that could combine all the complexities of my own life with my thoughts and feelings about my paternal family’s experience, and about the Palestinian/Israeli conflict itself. My approach to writing has never changed. Whatever I’m working on, whether it ultimately comes to life or not, is an opportunity to improve my craft and thereby to be ready to give the right book, when it comes along, the best chance for a sustained life.

Jamal “Jack” Shaban is a character of many contradictions — devoted yet flawed, he’s a community caretaker yet someone with deeply hidden personal histories. What drew you to write such a multifaceted protagonist?

Jack was facing me across the page almost the moment I began writing the book. I didn’t create Jack; I collaborated with him. As I was writing, discovering his past and following his lead, I didn’t think about why he made the choices he made. Now I have a little distance from the book, I can see him as a man with a past too full of love to cauterize, too full of pain to assimilate. He’s a kind of Janus, the Roman threshold god with one face looking forward, one looking back. Torn between the pull of the past and trying to have a future in America, he’s unable to cohere as a person. He compartmentalizes his life, becoming a different person at work than at home. His colleagues don’t even know he’s married. He’s lying to everyone. His predicament expresses in an intimate way the Palestinian (and Israeli) predicament of how to find a way forward given the suffering of the past. But, of course, this is true of all of us, even those without a traumatic history: the past dictates the way we emotionally respond to and categorize every new person or situation we encounter. We’re always negotiating a way to our futures through our pasts. In this way, Jack’s predicament is the predicament of us all.

As someone who bridges multiple cultural identities yourself, how did your own background and lived experiences inform this story and its characters?

Up until I was nearly four, my brother and I were living with my Irish mother in a small villa in the hills above Beirut. I spoke Arabic, played among the evergreens, red soil, and bright sun of those mountains. Then my father died, and my mother brought us back to dour, rainy London, a shift, I imagine, akin to a reversal of that magical moment in The Wizard of Oz when monochrome Kansas becomes technicolor Oz. I think I’ve always carried within me a sense of that lost world and language. My mother’s Irish brogue had been knocked out of her by the nuns at her Dublin convent school, replaced by the upper-middle-class English accent my brother and I spoke with and that was far too posh for the working-class neighborhood we lived in. We spent summers with my Palestinian family in Libya, Lebanon, or France and I would listen, fascinated, to their patois of English, French, and Arabic. The Irish and Palestinian/Lebanese cultures, clannish and absurdly hospitable, are far closer together culturally than either are to the English culture I grew up in. I never felt Irish, English, or Palestinian. I never felt anything but displaced, wrong in some essential way. I found childhood a profound trial, and as a boy without a father, surrounded by the unenviable examples of manhood provided by my friends’ brutish or alcoholic fathers, I had no sense of what to become, or of any future beyond this experience of wrongness and displacement. I can see now how all of this fed into Jack’s character and predicament, and into many of the novel’s themes.

My approach to writing has never changed. Whatever I’m working on, whether it ultimately comes to life or not, is an opportunity to improve my craft and thereby to be ready to give the right book, when it comes along, the best chance for a sustained life.

The novel weaves past and present — from Gaza to Chicago — in a way that reflects both intimate personal memory and broader historical weight. How did you balance these timelines and geographies? Did you create outlines or diagrams?

For a long time, I had been working on another novel based on the lives of my Palestinian family, a book that required painstaking research, including historical timelines. This meant that much of my sense of Palestinian history had been relatively well absorbed when I began writing Every Exit Brings You Home. I learned the technique required to weave past and present effectively from studying those who do it brilliantly. Mary Gaitskill is a master of this weaving of past and present. Her narratives aren’t just a mechanistic shift from a present timeline to a past one, but a complex integration, the past beginning as a separate and remote experience, but over the course of her stories slowly infiltrating and ultimately breaching up into the present. Such shifts from present to past and back can’t be imposed on a character. They emerge from that collaboration and negotiation between author and character that generates a novel. But the author is responsible for the balance of the whole composition, and to ensure that the transitions don’t feel forced or abrupt, but natural, seamless.

The book addresses global and local wounds — war, genocide, displacement, financial precarity, desire, and identity. Which of these themes did you find most challenging to explore and why?

Any novel that centers Palestinian characters is going to enter a distorted field of perception for readers who feel very strongly one way or another about the Palestinian/Israeli conflict. This is a hot button issue, particularly since the October 7 attacks and subsequent horror in Gaza. I have always stuck with fiction because my interest is in the human condition. The twin pillars of fiction are truth and intimacy, and the conflict in the Holy Land travesties both. What I found challenging was to write a book that could be read by people on both sides of this division of opinion without feeling the story had merely propagandistic intent. Jack suffers at the hands of the Israelis, certainly, but also at the hands of his own people. And he is certainly not merely a victim. Though compassionate and courageous, he’s a deeply flawed man haunted by his own capacity for evil.

I pull no punches about what life was like in Gaza after the 1948 war and then under occupation, but young Jack and his lover will discover an Edenic space within the madness, an abandoned house in Gaza. This creates the mythic subtext of the paradise that lies beneath even the most brutal and intractable conflict, intimating the possibility of a return to complete intimacy with the other, with oneself, and with God. Without this contrasting subtext, all that would be represented is the monstrous culmination of the Fall, the complete and murderous estrangement of one group of people from another. This isn’t a political novel; it’s a novel where Jack’s predicament, his struggle to reconcile himself to the past, to find some way forward, and to be a decent human being, is, I hope, a struggle most of us can connect to.

Throughout the novel, shame operates quietly but powerfully, shaping intimacy, secrecy, and the ways characters love and withdraw. What drew you to shame as such a central emotional force?

I think that people often have central energies that drive them, most prevalent of which (sadly, perhaps) are fear, anger, and shame. These energies burn at their core and can be very useful if their power is controlled — contained and intensified. Jack is driven by shame, a profound sense of wrongness in the world that no doubt reflects his history, including his sexual experiences, which are often fraught with shame, particularly in the refugee camp’s conservative society. His father, whom he profoundly disappoints, also feeds Jack’s shame. And, of course, on some level, Jack is my own dream self. I think shame is at the center of my own life, and feels congenital rather than acquired, though there are plenty of ways in which it was exacerbated, including by the British culture, which is a shame culture, like that of the Japanese. But I also think that shame is a part of the Palestinian predicament. The focus is so often on samood, steadfastness. But the Palestinians were made homeless and stateless — becoming nobodies — most crushingly in Gaza and Lebanon. They were vilified as terrorists, as lazy welfare cheats suckling the UNRWA teat, or as cowards who forfeited their homes because they ran.

I have always stuck with fiction because my interest is in the human condition. The twin pillars of fiction are truth and intimacy, and the conflict in the Holy Land travesties both. What I found challenging was to write a book that could be read by people on both sides of this division of opinion without feeling the story had merely propagandistic intent.

The title Every Exit Brings You Home evokes a paradoxical sense of departure and return. What does “home” represent to you in the context of this story?

Home is a complicated concept for any Palestinian, particularly one who grew up in a refugee camp inside the Occupied Territories. The camp inhabitants are refugees inside their own country. The camp is Not-Home, an eternal transitional space, a liminality. And yet it is Jack’s home, the place of his childhood, generating the mythos, the gods and monsters he carries into adulthood. Jack is also running from something: from his past and from himself. What drew him to becoming a flight attendant was the dream of eternal escape, all those gates that lead to other places he could potentially fly to. When he’s working, he’s constantly departing for distant locales, creating the illusion of escape. In the air, a plane is nowhere, a liminal space, and this is his true home in some essential way. But the final flight always returns him to Dimra, herself an embodiment of Palestine, unable to free herself from that history. The essential conflict within him — escape your past, you cannot escape your past; escape who you are, you cannot escape who you are — condemns Jack to be forever flying away from his home (from himself), forever returning. Hence the paradox of the title.

Gaza appears in the novel through memory, inheritance, and rupture rather than continuous presence. What felt most important to you in your portrayal of how events there continue to reverberate through its citizens across time and distance?

October 7 was a horror, but not a surprise. My novel ends with what was then called “The Gaza War,” in early 2009, the worst conflict between the Gazans and Israelis up to that point, but itself just one more in an escalating series of conflicts. Several people who read the advanced reader’s copy of the novel told me they felt as if the novel had somehow jumped ahead in time to this dire present conflagration in Gaza. While there is certainly a kind of clairvoyance that can happen when writing fiction, this present horror is also the inevitable result of a conflict rooted in injustice and a mutual sense of victimhood. Yeats’ poem, The Second Coming (and here we really see clairvoyance in action), might have been written about the Palestinian/Israeli conflict. “The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere/The ceremony of innocence is drowned;/The best lack all conviction, while the worst/Are full of passionate intensity.” And in the last line, the beast, of course, “Slouches toward Bethlehem to be born.”

Gaza is a prison and it is a home. It is part of a land unfortunately rooted in a myth half the world has been fighting for possession of for over two millennia (and by a myth I mean a story that incubates essential truths, not a lie). But day to day Gaza exists, as does every inhabited place in the world, in a multifold and intimate way created by the experiences, perceptions, and imaginations of its inhabitants. Jack imagines the doors of his home opening into the wide boulevards of early eighteenth-century Saint Petersburg. The city hides two lovers in a cracked and condemned paradise. Gaza is the center that is everywhere.

To write and read is a shared act of creation and connection. To live for a while in someone else’s life, a life seemingly very different from our own, is an act of intimacy and empathy that expands our emotional and spiritual scope, facing us with an “other” in whom we often recognize ourselves.

The narrative touches on universal questions about love, belonging, and sacrifice. What advice do you think readers will take away from Jack’s journey?

Very few of us are wise enough to take advice! Novels are all about people making mistakes, sometimes learning from them, but more often repeating them, and muddling through life. Like the rest of us, like Jack. A full life is a life of connections — both deep and casual — to others. For me, works of fiction are acts of intimacy. For most readers, a novel is a relationship, and of all our experiences in life, it is our relationships that most expand our understanding of ourselves and the world. A novel is conceived by means of the connection between author and character and is born during the connection between reader and character. To write and read is a shared act of creation and connection. To live for a while in someone else’s life, a life seemingly very different from our own, is an act of intimacy and empathy that expands our emotional and spiritual scope, facing us with an “other” in whom we often recognize ourselves. Jack is a unique person, with a singular experience, but to enter his being and life I hope allows the reader to find a new angle of entry into those universal questions you mentioned about love, belonging, and sacrifice. This is the kind of imagination that is entirely lacking in conflicts such as the one in the Holy Land. Novels may not provide advice or change the world, but they do keep the fragile flame of intimacy, empathy, and connectedness alight.

When writing about a community experiencing crisis, what conversations do you hope will spark beyond the page?

A community in crisis is a complex organism. I can imagine that people will talk about those attitudes and actions that might kill this organism altogether, and those that might allow it to survive and thrive. In the novel, the condominium building is a kind of microcosm of people struggling to share the same space, a situation that raises some of the same questions as more global conflicts. Does a community have compassionate leadership? Is the community unfairly stratified? Do the members of this community cultivate a sense of generosity and openness? And perhaps most significantly, how does a traumatized community move forward without leaving some of its members behind?

Naeem Murr, a dual US and UK citizen, is the author of four novels: The Boy, a New York Times Notable Book; The Genius of the Sea; The Perfect Man, which was awarded The Commonwealth Writersʼ Prize for the Best Book of Europe and South Asia, and was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize; and Every Exit Brings You Home, which was published by W.W. Norton in 2026. A former Stegner Fellow at Stanford, among his awards are a Pushcart Prize, a Lannan Residency Fellowship, a PEN Beyond Margins Award, and a Guggenheim Fellowship. He lives in Chicago and teaches at Northwestern University.