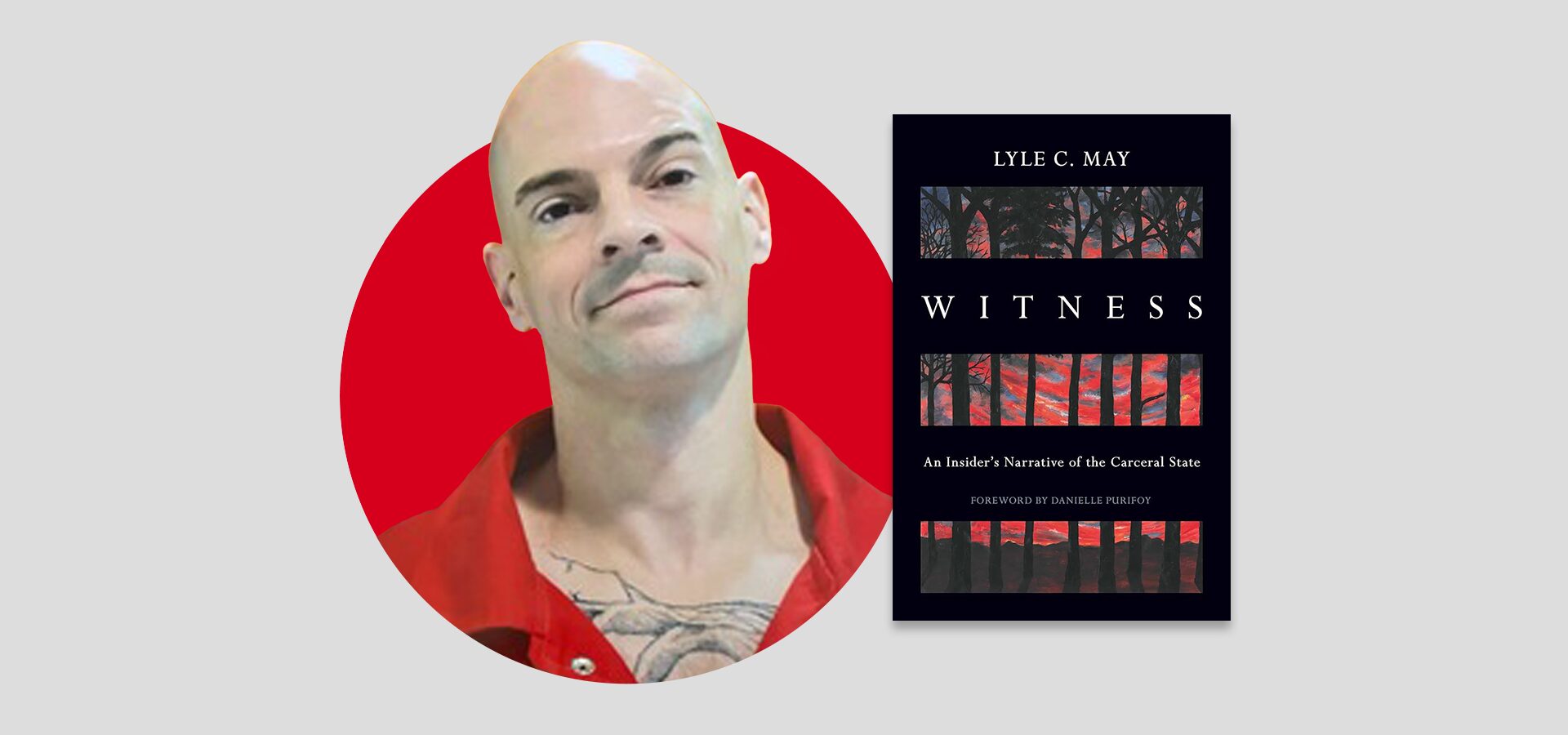

In 2015, Lyle C. May published his first essay, “Domesticated,” with J Journal, a justice-themed literary magazine out of the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. The essay was about a group of feral cats he and friends befriended while on death row in North Carolina. Nine years later, May published his first book, Witness: An Insider’s Narrative of the Carceral State (Haymarket Books, 2024), from the confines of that same prison. In Witness, May interweaves personal narrative with journalistic inquiry to report on what’s lesser known about capital punishment, and in the process he challenges misconceptions about the legal practice of justice in the United States.

In this PEN Ten interview with Malcolm Tariq, senior manager of editorial projects for PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program, May gives insight to collaboration, his reading practices, and how he came into his craft as a journalist. (Bookshop; Barnes & Noble)

I describe Witness as a collection of nonfiction written over the past few years. When did you realize the individual works could lead to a collection? Can you share your book publication story?

At some point prior to Witness, I knew I wanted to create a collection of Scalawag Magazine articles, but also knew I didn’t have enough for a whole book. It wasn’t until a friend sent me Miriam Kaba‘s We Do This ‘Til We Free Us, that my understanding of what a collection can look like that Witness began to take shape as an idea. I saw how Miriam’s book contained collected essays, interviews, and lectures. It struck me that I had a number of lectures I could incorporate with the Scalawag articles and essays I had published elsewhere. The same friend that sent me Miriam’s book also suggested I submit a proposal to Haymarket Books. She helped me send the pitch and they replied within six weeks that they wanted to see a draft. Once Haymarket saw that early draft of Witness, they offered to publish. I would like to tell you that at this point the rest was history, but the real work began in earnest. I ended up writing five new chapters, cutting two original chapters, cutting and revising a lot of the overlap between chapters, and making what had been a bunch of different essays, articles, and lectures into a smooth book. I also had a lot of help in this process. What I discovered is that getting a book ready for publication from the point of acceptance can be as much of a task as actually writing and producing each chapter, and it involves a team effort.

As it turns out, you had two books published this year, the other being “The Transformative Journey of Higher Education in Prison: A Class of One” (Routeledge, 2024). How did your writing process differ for these projects?

In contrast to Witness, the writing and publication process for The Transformative Journey of Higher Education in Prison: A Class of One was very different. I wrote it chapter by chapter at the urging of Dr. Amanda Cox. When she learned of my educational journey on death row she felt very strongly that it was a story people needed to know about. At the time I was also enrolled in a special studies project for advanced criminology with Dr. Cox as my instructor. Even as I was engaged in this course with her I added essays from the course into Class of One, making it more auto ethnographical and academic. Even before I finished all of the chapters we submitted a proposal for the book to several university presses without much luck. By pure happenstance, Dr. Cox’s friend and colleague, Dr. Lisa Carter, was at an academic conference when she bumped into Ellen Boyne, the acquisitions editor at Routledge. Ellen Boyne asked about a book proposal a colleague at another academic press mentioned receiving from Dr. Cox. She knew Dr. Carter was involved and asked to see it. When she got the proposal she submitted it to the editorial board along with two sample chapters. Then it went to a blind review by selected academics in the field who made recommendations. The proposal was accepted and about four months later we submitted the manuscript. The revision process was more removed than it had been for Witness. Publication happened soon after they received the manuscript.

There is the belief by some that you shouldn’t have to prove your humanity, it should simply be recognized. But if that were true, the death penalty and death by incarceration would not exist. The dehumanization of people different from us would not occur.

Writing is often a private and intimate process, and can involve varying levels of vulnerability. As a writer who weaves personal narrative into your journalism and nonfiction, did you have to prepare for your work to exist as a book read and critiqued by the public?

To be honest, my life for the last 27+ years has been under a public microscope. There is nothing like the very public humiliation and dehumanization of a capital murder trial. Once you survive that, if it doesn’t break you, and it has indeed broken many people, you realize at the bottom of the pit it’s all about showing and proving you are not the person they say you are. Criticism is intertwined with the desire to be heard, understood, and accepted. I never saw my writing as being vulnerable or intimate so much as a way to prove my humanity. There is the belief by some that you shouldn’t have to prove your humanity, it should simply be recognized. But if that were true, the death penalty and death by incarceration would not exist. The dehumanization of people different from us would not occur. Writing and getting articles published became a way for me to build a record of my humanity and that of my friends and peers inside. It was both an act of defiance to labels, and resistance to being thrown away. If there was any preparation for that fight, it occurred in the years of confinement on death row, in the executions of friends who never got the chance to prove their humanity.

I’m curious: what is your favorite essay from the collection? Or, which is most significant to you personally, if you don’t mind sharing?

My favorite essay/chapter of Witness is “Beyond the Wall.” This essay was something of a departure from the style of the other chapters. The illustration and emotional connection to the environment is very much a comparison between life and death. This essay is as much a glimpse into the crushing weight of long term confinement as an execution is for a death sentence. It is both a very poignant moment, and a sad one for everyone who dies in prison. Beyond the Wall is also the inspiration for the cover. The sunset I witnessed on that small hill was maybe the most achingly beautiful thing I have ever seen in my life and I knew in that moment there was no way to know whether I would see one again. The friend and artist who painted that image, Monica Randazzo, perfectly captured the colors juxtaposed against the darkness. If there is a single paragraph in all of my writing that strikes at the heart of my life in confinement it’s the last one in Beyond the Wall on page 83: “For the briefest moment, I remembered another life, where sunsets were normal and I didn’t drink from this world as though dying of thirst. Then it was gone, lost in the gathering shadows and sound of clinking chains.”

What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

There are a number of books I draw from in my writing. There is only one book I draw from in my spiritual relationship with God. But the book that has had the most profound effect on the purpose of my writing is Viktor Frankl‘s Man’s Search For Meaning. This book was the catalyst for all I would grow to be as a man on death row. I would revisit it several times over the years and glean new meaning from Frankl’s experiences in concentration camps during the Holocaust. Everyone suffers, writes Frankl. Therefore, we must define and own our suffering as an element of life. How we respond matters more than what we experience.

The reality of our society is that all language has power, and the less you understand, the more it will constrain your life and liberty. My experience with the criminal legal system and its use of language to take my freedom, erase my identity, remove me from society, and attempt to exterminate me is largely why I now study language and the law.

What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

It would not be until in 1997, after I was charged with a double homicide I did not commit, that I really experienced the power of language through my false confession and unrecorded interrogation, the short form indictment used to charge me with first degree murder in the most vague manner, and reporting on the case by local media. The reality of our society is that all language has power, and the less you understand, the more it will constrain your life and liberty. My experience with the criminal legal system and its use of language to take my freedom, erase my identity, remove me from society, and attempt to exterminate me is largely why I now study language and the law. Even this answer to your question taps the thread of power you mention. How? Because anything you say or write can be used against you in a court of law. Even as I prepare to apply for the Legal Revolution Prison to Law School Pipeline program I recognize there is so much to learn about the power of language to dictate the terms of my life and that of everyone in our society.

What was one of the most surprising things you learned in writing and publishing your first two books?

The most surprising thing I learned about publishing Witness and Class of One is that commercial publication and academic publication are very different processes, from acceptance all the way to launch of the book. With Haymarket Books it was more hands on and I communicated with an editor fairly often at every stage leading up to the book launch. With Routledge Academic Press it was very removed, I only spoke to an editor once, and there was no official book launch, rather, the book simply became available for purchase.

What other books would you say Witness is in conversation with, or what book should readers explore after reading it (besides your other title, of course)?

Readers of Witness should explore some of the books I used as resources for next steps in their edification on mass incarceration and the criminal legal system. I admit some of these will be heavy reading if you are not familiar with the subjects, but they are essential to understanding how public policy impacts the marginalized and why the criminal legal system is a public responsibility. There are several I will recommend here: Prisoners of Politics: Breaking the Cycle of Mass Incarceration (Rachel Elise Barkow), Deadly Justice: A Statistical Portrait of the Death Penalty (Frank R. Baumgartner, et. al.), Death by Prison: The Emergence of Life Without Parole and Perpetual Confinement (Christopher Seeds), Cruel and Unusual: Punishment and US Culture (Brian Jarvis), and Stephen Breyer: Against the Death Penalty (John D. Bessler).

You reach the point where writer’s block is a thing of the past, and now it becomes a process of molding and shaping the language so it is a tool in your hands. That’s the sweet spot.

What have you been reading? Which writers working today are you most excited by?

I am currently reading textbooks. Nothing I would recommend unless it’s a required course! Otherwise, I am dissecting parts of Project 2025, which is really kind of scary, in preparation to write about how it will impact the criminal justice system, people already in confinement, application of the death penalty. I look forward to how others plan to dissect it and will definitely want to see how they interpret the new conservative blueprint that will exponentially expand the Carceral State.

What advice do you have for aspiring and emerging writers and journalists?

The best advice I can give to aspiring writers and journalists is to constantly write. Immerse yourself in the subject you plan to cover. Read about and understand how it applies to you on a personal level. Connect with it at a societal level. In doing so you will never run out of ideas or subject matter. The blank page stops being intimidating and you suddenly realize there isn’t enough room to cover everything. You reach the point where writer’s block is a thing of the past, and now it becomes a process of molding and shaping the language so it is a tool in your hands. That’s the sweet spot. That is the place I would encourage every writer and journalist to work toward.

Lyle C. May is an Ohio University alum and member of the Alpha Sigma Lambda Honor Society. He is currently finishing a Bachelor of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies (Law and Business) through Adams State University, and is projected to graduate by the end of 2024. He is the author of two books, Witness: An Insider’s Narrative of the Carceral State (Haymarket Books, 2024) and The Transformative Journey of Higher Education in Prison: A Class of One (Routledge Academic Press, 2024). Lyle has received several honors, including a PEN Prison Writing Award, an inaugural Stillwater Award for Best Op-Ed, and a nomination for the Pushcart Prize. When not writing or studying, Lyle lectures on the politics and policies of mass incarceration in university classrooms, academic conferences, online events, in churches, and on podcasts both nationally and internationally. For more information, visit LyleCMay.com.