Lessons Out of Crisis

By Kyle Dacuyan

June is Pride Month—and an excellent time to reflect on what queer writers and resisters have done to advance new models of advocacy. Part of the important, enduring tradition of Pride is the community’s insistence on creative disruption. We disrupt the terms of public space, the boundaries of acceptability, notions of who and what should be visible or not. We bring forward demonstrations of joy, grief, and rage particular to LGBTQ experience.

These kinds of disruptions have everything to do with how words and stories are being put to work. AIDS activists, in particular, broke ground by envisioning new ways of verbalizing and staging civil disobedience. To honor that work, PEN America is convening a “Reading for AIDS Remembrance” this Thursday at the recently dedicated AIDS Memorial in New York City’s West Village. The reading marks a special occasion: the first Pride in NYC with a dedicated public memorial to AIDS.

In the lead-up to that event, let’s take a look at some of the specific ways AIDS advocates have tied writing with activism.

1. Coming Out

“To make the private into something public is an action that has terrific repercussions in the preinvented world.”

—David Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives

Monitoring what we share—and who we share it with—is a defining part of LGBTQ experience. What made the early creative response to AIDS so powerful was the decision made by many to broadcast their lives widely and loudly: from the frank realities of a completely different sexual culture, to explicit descriptions of deterioration, to the stunning grief of burying friends and lovers week after week. The importance of these stories should not be underestimated, especially when we consider that President Reagan did not even publicly mention AIDS until 1985, after more than 5,000 people had already been killed by the disease.

Writers pushed back against government silence by finding new ways to circulate their work and render their lives visible. Just a month before his death in 1990, Tim Dlugos appeared on Good Morning America to read selections from his epic poem, “G-9,” about Roosevelt Hospital’s AIDS ward. And a few years later, the Marlon Riggs documentary Tongues Untied appeared on PBS with footage of Essex Hemphill performing spoken word pieces about being a black gay man living with AIDS.

The outpouring of creative work about AIDS and queer life faced a conservative backlash—playing out, most notably, in attempts to withdraw, restrict, and otherwise suppress federal arts funding. But as David Wojnarowicz notes in the clip above, art ironically acquires public power when it wears the label of transgression.

With arts funding again seriously on the chopping block, I can’t help but feel that Wojnarowicz’s words ring as true today as they did in 1990—that there are concerted efforts to keep certain people invisible and silent, and that these are the voices most essential to our progress.

2. Taking Over

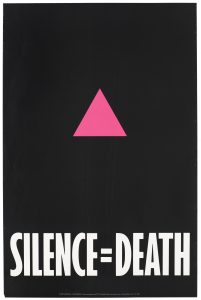

Before social media, before memes and viral content, we had leaflets, posters, and graffiti. By taking over public spaces with insistent text and imagery, artist collectives like Gran Fury pioneered new ways to run grassroots awareness campaigns. They filled coin-operated newspaper dispensers with copies of the “New York Crimes.” They plastered information about AIDS and AIDS advocacy on storefronts, park displays, buses, and other public signage. And they landed on the kind of rallying, imperative vocabulary—“Silence=Death”—that groups like Occupy Wall Street and #BlackLivesMatter have similarly adopted.

Before social media, before memes and viral content, we had leaflets, posters, and graffiti. By taking over public spaces with insistent text and imagery, artist collectives like Gran Fury pioneered new ways to run grassroots awareness campaigns. They filled coin-operated newspaper dispensers with copies of the “New York Crimes.” They plastered information about AIDS and AIDS advocacy on storefronts, park displays, buses, and other public signage. And they landed on the kind of rallying, imperative vocabulary—“Silence=Death”—that groups like Occupy Wall Street and #BlackLivesMatter have similarly adopted.

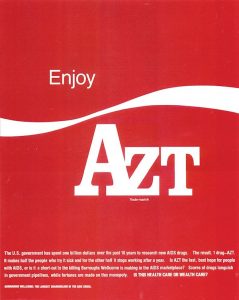

Another brilliant tactic Gran Fury introduced was the appropriation of public-facing design and sloganeering. The usefulness was twofold. This was, on the one hand, a practical means of disseminating material—it wasn’t immediately distinguishable to the quickly passing eye, just askew enough to hold someone’s attention. But it also cast a not-veiled critique at the ways corporate greed had stymied the delivery of care. As the sole treatment available in the first decade of the AIDS crisis, AZT became a target of derision for monopolizing the AIDS marketplace.

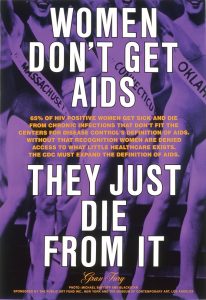

These takeovers of public space were public awareness and education campaigns—but they were also directed at substantively changing policy. When treatment initially became available, many women weren’t able to access healthcare because of how the CDC defined AIDS-related infections, even though minority women at this point in the 90s had the statistically highest risk of contracting AIDS. The relentlessness of this material in public space, particularly in urban public space, was crucial to shaping how information about AIDS was encountered in daily life.

These takeovers of public space were public awareness and education campaigns—but they were also directed at substantively changing policy. When treatment initially became available, many women weren’t able to access healthcare because of how the CDC defined AIDS-related infections, even though minority women at this point in the 90s had the statistically highest risk of contracting AIDS. The relentlessness of this material in public space, particularly in urban public space, was crucial to shaping how information about AIDS was encountered in daily life.

3. Speaking Back

A language of particular anger indisputably drove a response to AIDS. The precision of the word Plague, for example. Plague articulated urgency and spread. It was accusatory in its suggestion of a medieval moment. Plagues are matters of public and not individual health. They affect communities. This community found a way to harness that word’s fearsomeness and fury of neglect to mobilize for dignity and self-preservation.

Writers developed new formal terrain from their anger as well. I’m thinking of the performance poet Karen Finley, for example, seething, wailing and grunting through the text of “Drought”:

Writers developed new formal terrain from their anger as well. I’m thinking of the performance poet Karen Finley, for example, seething, wailing and grunting through the text of “Drought”:

One day it stopped raining tears

but rained blood

It rained blood and garbage and shit

No one knew where it came from

This was the only way to get people’s attention

The blood and shit landed on beaches

This was the only way to get people’s attention.

It’s startling, unprecedented language that throws respectability out the window. Finley is not asking for permission. She is kicking down the door. She is establishing new terms for what must be said and how.

And I am thinking of Tory Dent, who occupies a singular place in American poetry for her Whitmanesque chronicle across three books of living with HIV. From the time of her diagnosis at 30 until her death at 47, Dent dedicated her poetic practice to inventing new long-lined, sequential forms, work that builds a landscape of physical pain, experimental treatments, and what Adrienne Rich called “the rage to live.”

The language of anger runs counter to the language of disease—to the expected narratives of weakness, shame, and secrecy. It is both unifying and oppositional. It is language from which we can learn new ways to act and demand.