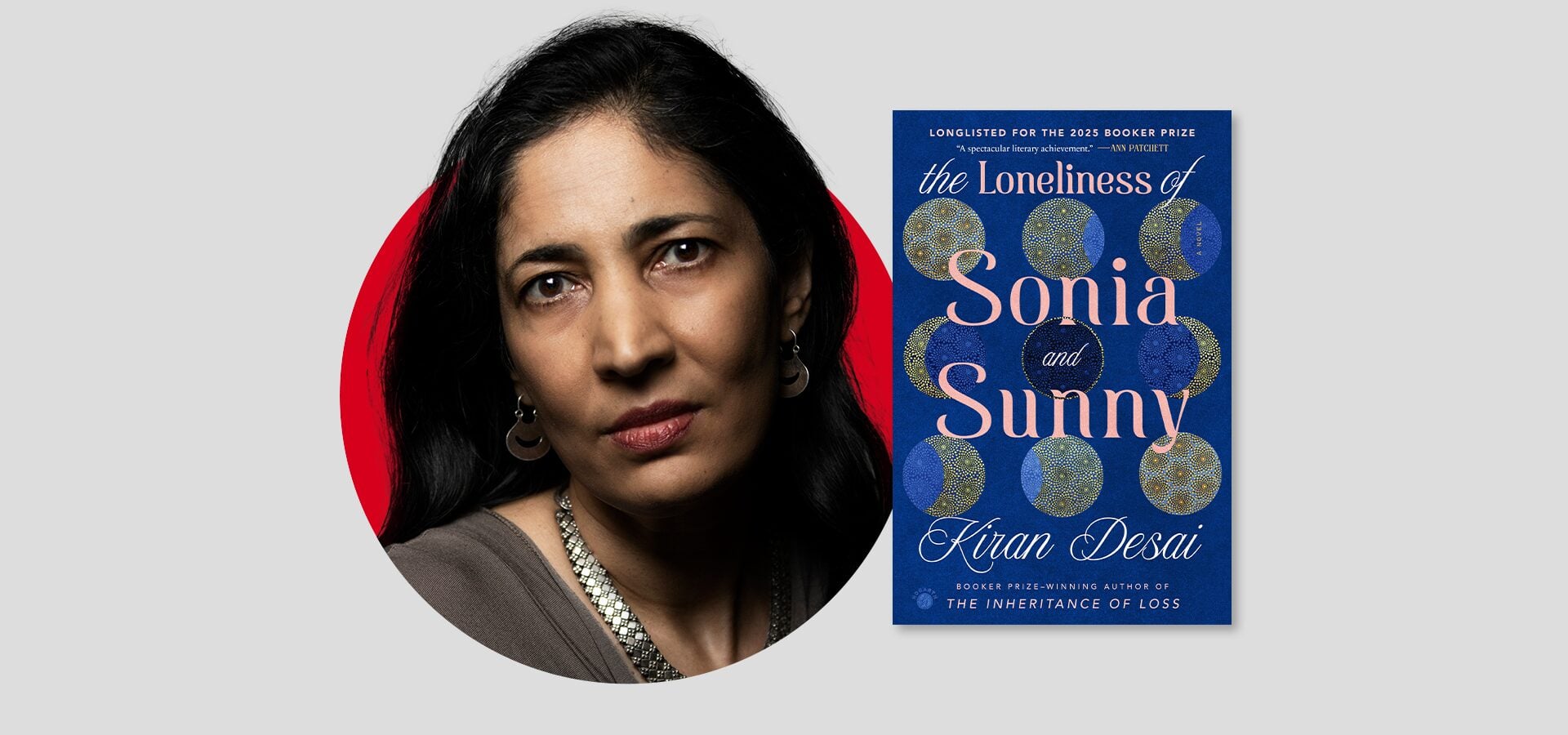

Kiran Desai | The PEN Ten Interview

Kiran Desai’s long-awaited third novel The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny (Hogarth, 2025) is a rich and sprawling epic about love and loneliness—not just of its titular characters, but of every character, creature, and crevice that lives within its pages.

In conversation with Membership and National Engagement Coordinator Abhigna Mooraka for this week’s PEN Ten, Desai discusses the process of working on a book for almost two decades, the role of fiction in the political sphere, and the many centers, off-centers, and in-betweens of her newest novel (Barnes & Noble, Bookshop).

The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny comes nearly two decades after The Inheritance of Loss. What does working on one project over such an extended period of time look like?

I didn’t notice the years passing. I merged my life and my art almost completely. Life feels thin on the other side of this novel. I consider it one of the great fortunes of my life to have been able to work in this manner.

A guava orchard appears in the very first chapter of the book, as does a reference to Ba’s inheritance of her mother’s loss—a Burmese ruby. In what ways have your first two books, and your past selves, made their way into your newest book?

I think over time, distilling histories, distilling meaning, an artist comes up with a personal cosmology of symbols, images, memories. And perhaps, an immigrant author recalling past lives links herself to talismanic objects, or a few lines from a song, a few photographs. I think of the beautiful Borges poem, “Boast of Quietness.” I think of Garcia Marquez and the banana plantation of his childhood, the massacre, his grandparents’ home, all of which became the root of his understanding of politics and history, history that muddled journalistic accounts, personal accounts, superstition, hallucination, fantastic tales.

I was a city child, and visiting my grandparents was essential to my future work, little did I know it then. The guava orchard by the side of their bungalow, their mysterious personalities that belonged to the past, their arc of history. The town was provincial, but it had once been prominent. They barely left their veranda, but I understood they had made enormous journeys from a small town in another part of India, to England and back; from British India to Independent India. The lost ruby refers to a lost history, which was the history of Indians who were forced to leave Burma, and who left in successive waves. I could also use the ruby to write about the primitive greed Indian women have for jewelry. It is adornment, wealth, inheritance, beauty. But a jewel has deeper spiritual meaning in Hindu and Buddhist philosophies, of course. This also became important. Each new book is rooted in past books. I see my work in a continuous arc.

Sonia struggles with her writing because she “can’t put the center in the center.” How did you find the center of this story?

Sunny and Sonia are both trying to find love and home as they negotiate a world without a center, and as their sense of self turns more and more fluid. They learn lesson after rude lesson in failing to locate their own story, having perhaps mistakenly assigned the center to countries that are not their own, or to individuals who ensnare them. Their claim upon each landscape feels false and unfair, including their claim upon the country of their birth, because they have been brought up to leave, to dissociate themselves from India. More deeply, though, they learn that belonging is nothing more than perspective, there are always other claims upon a landscape. I eventually realized that the non-space, the no-center, was the center of this novel, those in-between places and the unseen world, the idea of the void that gives birth to phantoms, but also to powerful shamanic images and dreams.

Their claim upon each landscape feels false and unfair, including their claim upon the country of their birth, because they have been brought up to leave, to dissociate themselves from India. More deeply, though, they learn that belonging is nothing more than perspective, there are always other claims upon a landscape.

It isn’t just Sonia and Sunny who are lonely—it is also their parents, their grandparents, their ex-lovers. So are the cooks and the maids and the dogs. Amid this pervasive loneliness, they all seek change, albeit in different ways—upward class mobility, immigration, reverse-migration, assimilation, ambition. Do you believe that fiction makes a good vehicle for social commentary?

Especially when it comes to exploring the thoughts we have, that we would not confess to anyone, maybe not even to ourselves. The vocabulary of class and race out in the public sphere is not how we privately think about class and race. And the historical narrative often contradicts the personal narrative. We plot and plan changes to our circumstances, we are ruthless, we proclaim otherwise, we rewrite history. We are ashamed and scared, we cannot confess these emotions. And how do emotions like shame, fear, loneliness, rage manifest in the political sphere, as well as in the personal?

There are many recurring elements in The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny—the ghost hound, the kebab recipes, Badal baba—and they are so successfully woven together. How did you wrangle the many threads of this story?

Thank you for saying they are successfully woven together. I still wonder if they are. I sometimes find it helpful to think of a book like a piece of music, with recurrent rhythms and echoes. And I was aware that I was working with the plot on one level and simultaneously with the shadow world. Once I had Badal Baba, hermit of the clouds, who can shift shape, he needed company, or he might not have signified in any profound way. The ghost hound is a form of hallucinatory fear, is a form of Badal Baba. Aesthetically, it was difficult to write about the real world shading into the surreal. The kebabs were playful and more easy to work with.

Simplicity, in this book, is at one point described as that “of a man who has newly arrived, unshadowed by the history of the place he has arrived in, so long as he doesn’t try to learn it.” Many different histories leak into your characters’ lives—the partition, 9/11, the demolition of Babri Masjid, the Gujarat riots. How do you wield the violent histories of the world and not lose the simple humanity of your characters?

What is a fresh, new country to immigrants leaving complex, difficult pasts, is, of course, also a country with its own heavy burden of history. This is a book about people who do not experience violence directly, but yet are people whose lives are molded by history, by conflagrations of violence that confirm a dark, persistent undercurrent. The demolition of Babri Masjid, 9/11, and the War on Terror changed many things for many people around the world, and yet we are still concerned with how to find love, how to be alone, how to get through a day while seeking a moment of laughter.

What is a fresh, new country to immigrants leaving complex, difficult pasts, is, of course, also a country with its own heavy burden of history. This is a book about people who do not experience violence directly, but yet are people whose lives are molded by history, by conflagrations of violence that confirm a dark, persistent undercurrent.

I loved reading phrases like “chota pota phaltu baba” and I especially loved reading them as they sneaked up on me in a sentence, unassuming and unitalicized. What were some of the linguistic choices you had to make for a story that travels so far into the world and so deep into the local?

This was a decision made along with my editors who agreed that a globalized story meant a story without a particular center, including no particular publishing center. So the words are unitalicized the way they would be for the characters speaking them, encountering them. A bit of Spanish, a bit of Italian, a bit of Hindi. I myself love a book with lines that I cannot understand. It forces me to inhabit new words, intuit their meaning, relish their sound.

Writers in the diaspora are often overwhelmed by the fear of writing inaccurately about the homeland, and writers in the homeland are limited by its boundaries. As a writer who has lived both lives, how has immigration shaped your writing?

I remember being worried when I left India, that I was losing my deepest subject, that I would not be able to write about a new country with intimacy, with an intuitive understanding, that my work would be limited to an immigrant narrative. Yet, of course, as you observe, immigration gives one a larger world to write from, and a new vocabulary and perspective. It tutors one in the endless possibilities for reinvention. Certainly the old worry hasn’t left me, but I find that I can work from the diaspora, from an in-between place. It is, in fact, a fascinating and exhilarating place to work from. The story is always in flux.

Sunny gets his first real opportunity as a writer through a PEN travel grant. Sonia finds her writing voice through assignments for an arts and culture magazine. What role have literary organizations and communities played in your own writing life?

Yes, I wrote a satire of New York literary galas because they are certainly worthy of satire, yet I am extremely grateful to all the many wonderful organizations that support the arts. There is a reason the U.S. has an extraordinarily vibrant cultural and literary world. I was supported by the Guggenheim foundation, the American Academy in Berlin, several residencies. I slept in the room where Sylvia Plath had slept. There were ideas I reaped in Berlin, that I hope to work on in the future. I would not have been able to write my Italian chapters were it not for the generosity of residencies and individuals in Italy.

I remember being worried when I left India, that I was losing my deepest subject, that I would not be able to write about a new country with intimacy, with an intuitive understanding, that my work would be limited to an immigrant narrative. Yet, of course, as you observe, immigration gives one a larger world to write from, and a new vocabulary and perspective.

Ilan’s voice echoes throughout the book: Don’t write about magic realism. Don’t write about phony pseudo-psychology. Don’t write about oriental rubbish. Don’t write about arranged marriages. Don’t write about painters. In writing this book and telling this story, you are subverting your own character’s writing advice. Was this real advice you received, and is there any advice you’d like to counter with?

I had fun with these warnings. Dissecting them. They make sense. They make no sense when you switch perspectives, when you broaden the scope of the narrative, include counter arguments. Magic realism is a very annoying term, in my opinion, and a false one. What makes a false work of art, what a real one? Exotic to whom? Who dictates what a book should be? My own advice is to try and make as true a work of art as you can, ignoring any and all advice.

Kiran Desai is the bestselling author of two novels, Hullabaloo in the Guava Orchard and The Inheritance of Loss, which won both the Booker Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award. Born in India, she came to the US when she was sixteen and now lives in New York City.