Students deserve to be able to read educational resources and works of literature that “reflect their identities and the complexities of their lives,” Jonathan Friedman, PEN America’s director of Free Expression and Education Programs, testified.

Friedman said what’s at stake in today’s movement to ban books is “Whether we can live in a diverse society that upholds our traditions of freedom and democracy for us all. Or whether we want to allow a vocal minority with a discriminatory intent to narrow our students’ educational horizons.”

Friedman testified before the House Subcommittee on Early Childhood, Elementary, and Secondary Education Hearing in an Oct. 19 hearing, “Protecting Kids: Combating Graphic, Explicit Content in School Libraries.”

Jonathan Friedman’s Opening Statement

Chairman Bean, Ranking Member Bonamici, and distinguished members of the Subcommittee, thank you for the opportunity to testify today.

My name is Jonathan Friedman and I serve as Director of Free Expression and Education Programs at PEN America. PEN America stands at the intersection of literature and human rights to protect free expression in the United States and worldwide. We are a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization with an unwavering commitment to free speech, a principle that we view as an underpinning of democracy and a cause above politics.

Today we face an alarming attack on free expression — on the freedom to read, learn, and think. Organized groups of activists, and some politicians, have launched a campaign to exert ideological control over public education, unprecedented in its scope, scale, and size.

In 2021, after speaking with authors about rising efforts to ban their books, first in Texas, but soon after, in Florida, PEN America launched a research project to track and record book bans nationwide.

Our most recent report of the 2022-23 school year recorded over 3,000 instances of books banned, an increase of 33 percent over the year prior. These bans occurred in 33 states, across 153 public school districts.

Since we started our research, we have maintained a clear, consistent, and transparent methodology with one guiding principle- student access.

If on Monday a student has access to a book and on Tuesday she doesn’t, as a result of a challenge over that book’s content, ideas, or themes, then that book has been banned.

For that student, ready access to the book has been diminished or entirely restricted — whether that book is now locked in an administrator’s office, moved to an upper grade library, or permanently removed from circulation. Or whether that book eventually gets returned to the shelf, after some indeterminate period of review. For the duration that student can no longer access that book, it is banned.

Why?

Because the circumstances surrounding such decisions are rooted in efforts to restrict access to information and ideas, implicating students’ First Amendment rights. And in our society, “the loss of First Amendment rights, even minimally, is injurious.”

Let me be clear: Parents play a primary role when it comes to their own children’s education. That’s why schools have Parent Teacher Associations, parent-teacher conferences, and public school board meetings. I am a parent of three school-aged children. I check my kids’ homework, read books to them, and advocate for them when the need arises.

But we can — and we must — distinguish between a single parent raising a concern and the current campaign to disrupt public education writ large.

Between a parent who wants to accommodate a kid’s learning needs, and one who grabs a list of books online they haven’t read, and then demands that no other family should be able to access them in public institutions.

Our students deserve to be able to access high quality educational resources, to access works of literature that reflect their identities and the complexities of their lives.

Not every book is for every kid. Not every book is for every family. But the unifying principle is that a wide variety of choice means kids and families can determine what’s relevant to them.

That’s the purpose — and power — of a public library.

Around the country, this liberty is being turned on its head: remaking schools and librarians from educators into censors.

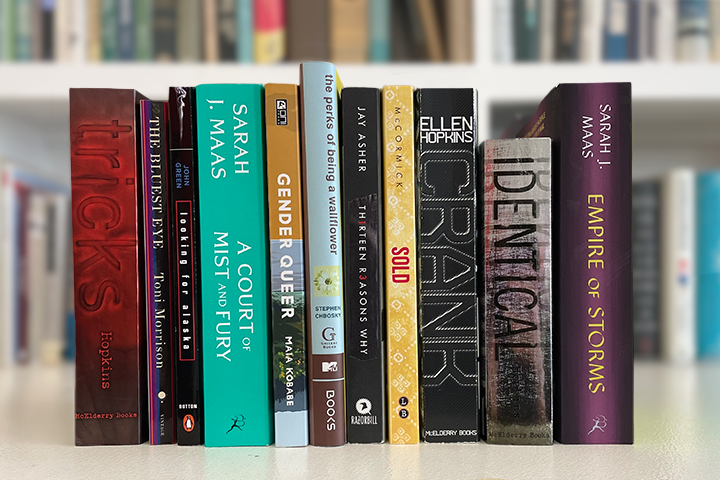

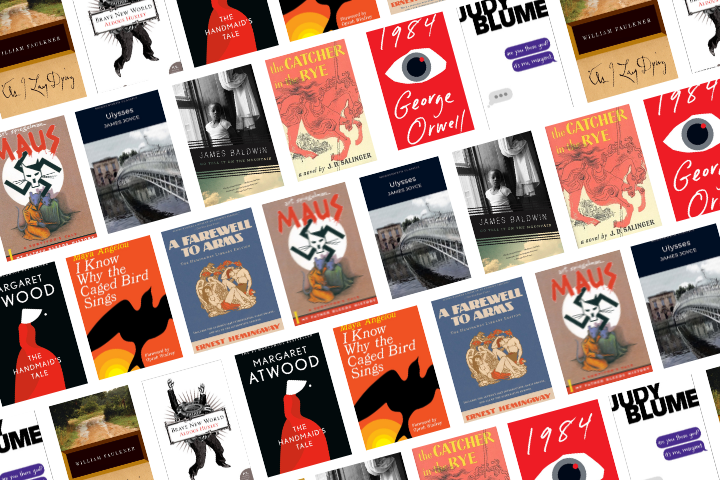

And again and again, we see targeted, organized, and replicated efforts to ban books with protagonists of color, books about African American history, books about LGBTQ identities. Efforts to take away the very books that many students, families and educators say they want to access. Books that they say save lives.

Over the past two years, I have spoken to teachers, librarians, parents, and students across the country. The stories I’ve heard are dire. Some have experienced direct threats. Others have been told that if they teach certain subjects, order certain books, or fail to ban certain books, it will put their career in jeopardy — or worse, will lead to them being charged with a crime.

I’ve spoken with authors whose works have been mischaracterized and attacked. Over 1,200 authors were affected by the bans in the past school year alone.

Ask any one of them why they write. Over and over they say the same reasons: to help kids see themselves and allow others to be seen; to provide kids the books they wish they had when they were growing up.

As poet Nikki Grimes says: “To plant seeds of empathy and compassion.”

That’s what’s at stake in today’s movement to ban books. Whether we can live in a diverse society that upholds our traditions of freedom and democracy for us all.

Or whether we want to allow a vocal minority with a discriminatory intent to narrow our students’ educational horizons.

Banning books doesn’t protect kids. It makes them less ready to function as informed citizens in the real world.

Thank you.

Read the full written testimony submitted to the subcommittee.