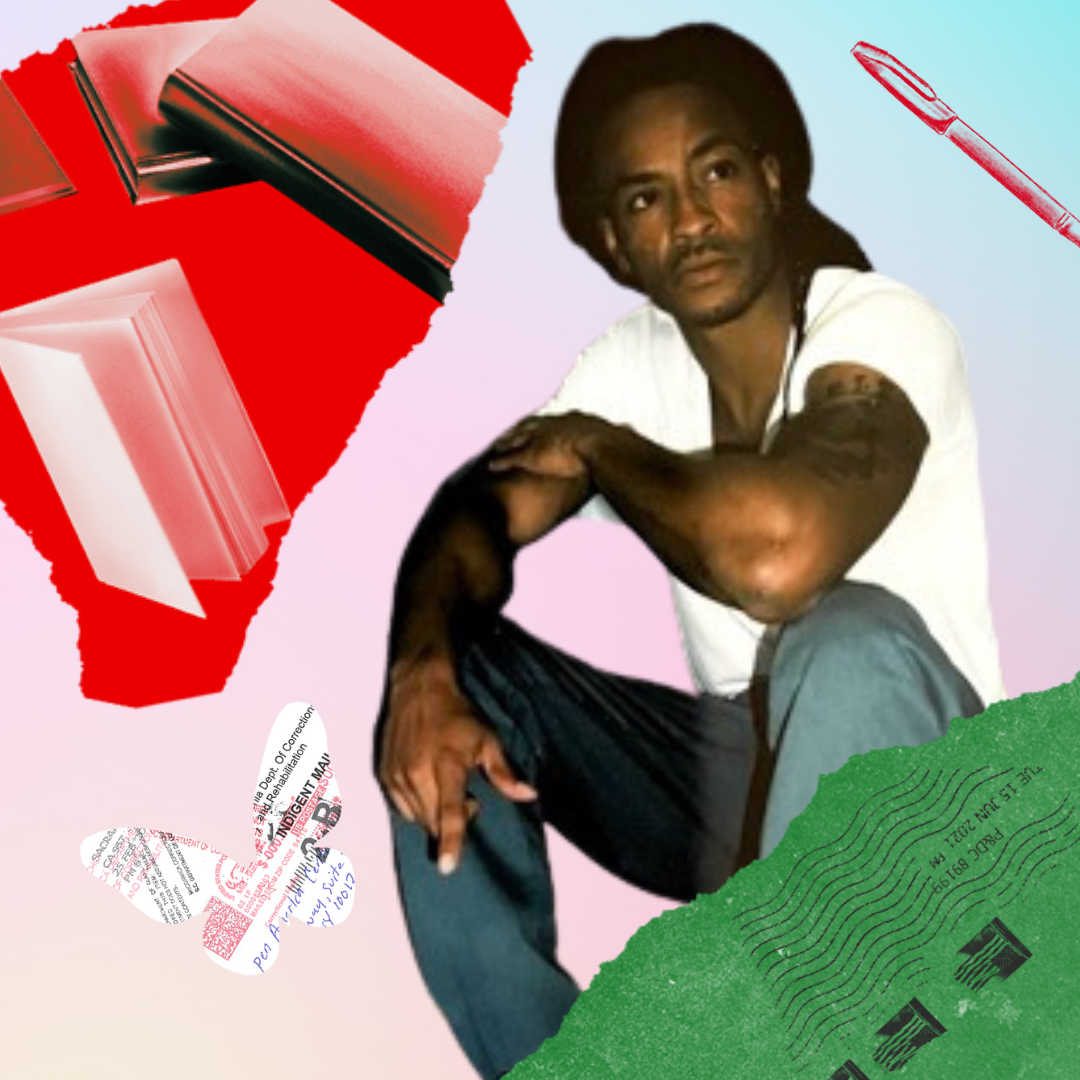

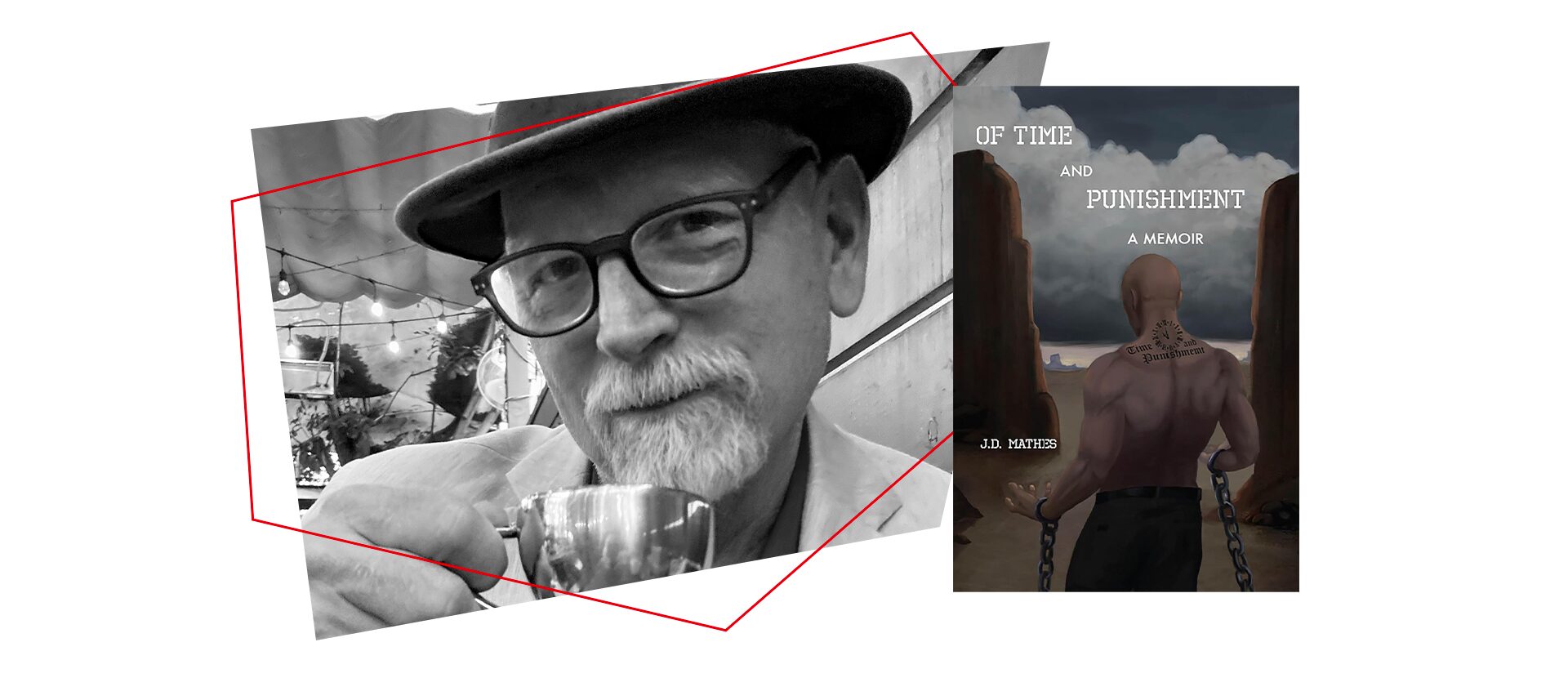

In a conversation with the Prison Justice and Writing Program’s Mentorship and Community Engagement Intern Ana Palacios, JD Mathes discusses his longtime engagement with PEN America, his creative process, the discipline of writing through uncertainty, and his thematic strategies for writing about justice. (Bookshop, Barnes & Noble)

Beyond your incarceration, are there other experiences that have motivated you to follow a path related to justice such as your long time relationship with PEN, your time in the military, or fighting wildfires?

I want to step back from this idea that outside forces may have pointed you in a particular direction. It’s also your own internal drives that aren’t just you—they’re also your parents, your grandparents, your culture. I was born into an interesting family. My father was a Goldwater Republican, but he was an evidence guy, and he taught me that Carl Sagan said, “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence,” and by virtue, any claim demands evidence. I was driving across country listening to Rush Limbaugh on the old AM radio. He was making all these wild claims about the Clintons and democrats. I kept waiting for him to present the evidence to support what he was saying, but it never came. I discovered it doesn’t add up. There’s no evidence for these things. So, ideologically speaking that was the start of what broke my beliefs. The seeds of breaking me out of that were given to me by the very culture that I was in and the main driver that sent me down this path.

As far as the military, my service was informed by my father who was a Vietnam veteran. But it wasn’t until I became involved with PEN America that I thought about the military in terms of social justice. I had come to an impasse on a book I was working on and as I was thinking about it, I conceived of researching a book about veterans and mass incarceration. That became one of the first times I started to think of my experience as a veteran, which I hadn’t thought about very much. I ended up publishing an essay, “The Homelessness of the Brave,” in War, Literature & the Arts, published by the U.S. Air Force Academy from that research.

My experiences as a wildland firefighter for fourteen seasons and a commercial fisherman up in Alaska for three seasons gave me the experiences to write about the environment. But again, what really shaped me was the culture I grew up in. At one point, I lived in a tent for 18 months as a kid in the desert making a homestead. Then we lived in mining camps or small farms, so, I’ve always been close to nature, but I’ve also been close to industry. I started thinking about those things in terms of conservation, game conservation, and the environment. I’ve begun a project about the drastic change in the fire regime of the Great Basin and the American southwest through the lens of the desert tortoise that was inspired by a fire briefing I attended in Nevada.

As a PEN America member and former Writing for Justice Fellow, what do you think writers need most in this climate of censorship and surveillance?

We need to continue fighting for our freedom of expression. I’ve always fought for the First Amendment and other people’s rights even when I wasn’t writing about it. We have conservatives talk about justice in the American way and being faithful to the Constitution, but then they attack the First Amendment through banning books, art, ideas, and suing journalists and news outlets that report news they don’t like. They have always led the attack of expression and limiting education based on religion and ideology. On the left we see attacks at publishing houses lobbying not to publish books or silencing (cancelling in the social media context) authors who don’t suit their ideology.

Regardless of who is trying to censor writers, what’s needed is a grassroots approach — more people like us putting it out there culturally, however we can, because that’s how power shifts. So yes, we can give up hope, then get back in the chair. One person at a time makes a crowd. Get your friends involved, then a third person joins, and it becomes a movement that scares those in power. Remember the Vietnam War protests? It seems glamorous on TV, but it was grassroots.

Regardless of who is trying to censor writers, what’s needed is a grassroots approach — more people like us putting it out there culturally, however we can, because that’s how power shifts.

In your own experience, how have narratives about prison transformed through the years? Do you find that your writing has changed along with the evolving needs and struggles of those affected by the justice system?

We’re used to the narratives of people exploring or justifying how they got to where they are, like in Ed Bunker’s Education of a Felon or Malcolm Braly’s False Starts. In the case of Jean Genet, he fully embraces the criminal life.

There are all kinds of witness testimony narratives, even John Cheever’s book or Stephen King’s Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption. But we’ve seen more academics tackling incarceration narratives. They’re trying to illustrate points—ideological points—about things like racism or mental illness in society. Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow is non-fiction; not a narrative per se but it’s opening this box and looking into it saying: look at these problems. Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption by Bryan Stevenson or Waiting for an Echo: The Madness of Incarceration by Chirstine Montross are other examples.

Also, there are the investigative journalists who get jobs as prison guards to write about it from that perspective. Ted Conover’s Newjack: Guarding Sing Sing or Shane Bauer’s American Prison: A Reporter’s Undercover Journey into the Business of Punishment. In the end those books are more about the reporter than the inmates.

As far as influence, though, I think the book that has influenced me most was Kiss of the Spider Woman by Manuel Puig. Its focus on two inmates, and how they change through their forced confinement together distills for me the personal way prison affects people. You can see it in my memoir. In my novel, I am exploring relationships between inmates over time because of Puig’s book.

In writing and about justice-related concerns, do you find there are expectations for formerly and currently incarcerated writers?

A lot of this is shaped by culture, and what culture wants. But those things are like fashion, right? Those things change. The book system has become homogenized.

The kind of thing I look at: What is that unique thing that I could write about? Of course, I’m bringing my own story. What’s the difference between that experience and these others that I would write about? And what angles are there within my story?

Around the time of George Floyd’s murder, agents and editors wanted to focus on stories by people of color, especially those invested in the carceral system. And so for me—not a person of color—I had to ask: What do I write about now?

You just roll with it. I get why these stories are being prioritized. But me, as a writer and artist, I still have to figure out how to work this out.

This is the inspiration for this memoir.

In memoir writing specifically but in writing or crafting a narrative as a whole, how do you decide what will give shape to the experience, what do you look for?

Sometimes I think, Okay, I’m just going to write it like this, and so I just start writing. I try to figure it out.

This memoir specifically—I actually wrote it in several different ways. I tried to write it as autofiction and experimented with episodic chapters.

I got a gig with Rehabilitation Through the Arts in New York to write a short screenplay for men about to be released from prison. They wanted a 10–20 minute narrative that shows the obstacles they’ll face—and how to come to terms with them. That’s my jam. I’d lived that; I fell off the wagon in the halfway house. I never thought about it in those terms before. It was all still new to me.

What I realized is that the halfway house is the frame of my story. It’s contained within an authoritarian system, but you’re allowed to go out and be “free” for a while—in Las Vegas of all places. And within that structure, I hope the reader feels that frustration of trying to fit back into society and resist the temptation just outside. Even if they don’t have addiction issues, that the sympathetic imagination kicks in and they understand my world that I’m there. I did that.

Each work has its own shape and the writer’s job is kind of like search and rescue. You write the story until you find it.

In the novel I’m working on now, Flight of the Monarchs, it explores in the first-person, present tense narrative a young man who is arrested. The reader learns what it’s like as he learns to survive, how his previous assumptions were flawed, and how the system changes his identity. The novel is going to focus on how authoritarians interact from the top–-the system–and the bottom–the inmate population–to control and crush those people who were like me, who are alone and adrift within all these competing totalitarian forces. The book’s structure hinged upon my idea to have the reader learn with the protagonist as he serves his time.

Getting that fellowship set me free as a writer. We talk a lot about how fellowships can open opportunities for people. But for me, it transcended all of that. It unburdened me, it unchained me. It unincarcerated me, if you will, because it was no longer a secret.

You have a long-standing relationship with PEN America, from being a 2019-2020 Writing for Justice Fellow to being an active member of the organization. How did this experience as a fellow help shape the development of your forthcoming memoir, Of Time and Punishment?

I had not been writing about prison issues or my experience with it until 2019. That’s a lie—I was writing about it, but I was writing very badly about it and I was trying to come to terms with it, but I wasn’t still telling anybody.

From 2012 to 2019, I’d been trying to write this narrative. In the meantime, I published another collection of short stories, Shipwrecks and Other Stories. My memoir, Ahead of the Flaming Front, came out the same time as my essay collection Fever and Guts: A Symphony did. I kept writing other essays and I wrote a bunch of screenplays, and I kept working on this. It always turned into a giant mess. What was missing?

I kept thinking that if I could publish something about my time in prison then I’d have to admit the truth and tell everybody. Then I saw something pop up for the PEN America Writing for Justice Fellowship and got in on my second application. So that was the wash your hands moment; Now I’ve got to tell everybody.

How did it then affect my writing? I started becoming really serious about it. Getting that fellowship set me free as a writer. We talk a lot about how fellowships can open opportunities for people. But for me, it transcended all of that. It unburdened me, it unchained me. It unincarcerated me, if you will, because it was no longer a secret. The PEN America Writing for Justice Fellowship allowed me the freedom to speak out loud and to confess to you, to me, to myself, and everybody around and ask forgiveness and try to find atonement and redemption. That allowed me to write this book. That extends to the novel I’m working on now as well.

I’m free now to write..

Many who work in or hope to work in justice-related fields may often feel helpless, as if there is nothing they can do. As writers, we often confront a certain amount of ‘existential’ questions about the value or importance of our work. What advice would you give to those questioning themselves and their work?

It’s dispiriting. I’ll tell you. As a writer focused on social justice, especially prison issues, this is a huge weight, a huge burden.

I always keep in mind a poem I recited at my daughters’ births. Walt Whitman’s “O Me! O Life! He says “life exists and identity, / that the powerful play goes on, and you may contribute a verse.” You may not change the needle of world politics, but together we can.

The only thing we can do is keep writing. I think about how megastars like Oprah or Taylor Swift’s audience didn’t seem to change a thing. But perhaps it’s because they are so big that they are easier to ignore. I like to think when writers like you, me, my buddies, keep writing, we’re an army—we can run this race. We fall when bigger forces come along and people aren’t paying attention, but we come back. We are the faceless mass of writers and artists who put it out there every day. We may not immediately change many people, but by degrees, we will.

I rarely get validation like fan mail or invites to public speaking events, but sometimes someone emails and says, “About that PTSD essay you wrote…” An editor once jumped out from behind a table and gave me a hug. Those are small victories that keep me going.

People often quote Dr. King that the moral arc of the universe bends towards justice. It only bends if we all stand on it. It doesn’t naturally bend that way. We can give up hope for a bit, but then we should get back in the chair and start writing or back in the studio and start painting, sculpting. We should get back on that stage and act. Whatever it is that you do, one person at a time makes a crowd of people.

We create a mass like a black hole drawing light toward us. We see the ring of fire around us. We must keep the faith and not give up. I think about giving up every day. What are we gonna do? The pop stars can’t get us through either. All of us, piece by piece, though. That’s all I can say. Ask yourself every morning, “What’s the point? Then get back in the chair.