Isle McElroy | The PEN Ten Interview

September 19, 2023

With humor and tenderness, Isle McElroy’s People Collide (HarperVia, 2023), riffs on the body swap genre using it as a launching pad to explore intimacy, marriage, and gender. When Eli, an American expatriate in Bulgaria, wakes one day to find himself in the body of his missing wife Elizabeth, he embarks on a search across Europe to find his missing body and the wife whose body he now inhabits. Along the way he questions his marriage, his relationships to his old and new body, and whether he truly knew his wife, all the while dealing with his mother, his in-laws and a terrorist attack as his wife.

In conversation with World Voices Festival Associate Director, Sabir Sultan for this week’s PEN Ten, Isle McElroy discusses character work, intimacy, and the art and writers that excite them. (Barnes & Noble, Bookshop)

1. People Collide is your second novel, following your 2021 debut The Atmospherians. How was approaching your second novel different from approaching your first? Did the warm critical reception to your first novel add any pressure to writing and publishing your second?

I was fortunate to have begun People Collide before The Atmospherians was published, which helped take away some of the pressure of beginning a second novel. Overall, I felt a little bit more confidence knowing that I could write a novel. I don’t know if this made the process easier. But it made the goal seem attainable. As for the critical reception, it did add a little bit of pressure, but I also felt like I had a clear view of what my first book didn’t accomplish, which gave me something to aspire to with the second.

2. At the start of People Collide, the novel’s protagonist Eli awakens one day in the body of his wife, Elizabeth, and later finds Elizabeth in his former body. After they switch bodies, the Incident, how they refer to themselves and their bodies, both present and former, muddies and shifts. How did you conceive of maintaining legibility for the reader while blurring the lines between Eli-as-Elizabeth, Elizabeth-as-Eli, and their current and former bodies?

Well, part of me thinks that I didn’t really maintain legibility! And that was intentional in some of those scenes. For instance, Eli remains unsure how to refer to Elizabeth when she’s in his body and sometimes loses track of how to refer to himself. When legibility was necessary, though, I tried to focus on who each one was to each other, instead of how others would perceive them (their physical bodies). But part of the fun is muddying those lines between the characters. Overall, though, I tried to keep distinctions between how each character speaks. If a reader gets lost in the scenes of them together, dialogue frequently offers a chance for grounding and differentiation.

“It can feel amazing to be taken care of, to be known, but it can also feel limiting if one is shown things about oneself that are difficult to confront.”

3. Once Eli and Elizabeth switch bodies, they each experience the lived-in, sex-based experience of the other’s body. Eli-as-Elizabeth must navigate the world in the body of a woman and Elizabeth-as-Eli in the body of a man. How did you approach mapping out what those experiences would look like for each of them?

Mapping out their different experiences required me to think more deeply about who Eli and Elizabeth are as characters. I wasn’t interested in creating a generic portrait of a man and woman swapping roles. In order for it to work, I think, each person had to respond to the Incident in ways most suited to their experiences. For instance, Eli feels compelled to care for Elizabeth’s body because he feels responsible for her–though he often fails to care for it as he intends. And Elizabeth, who resents the mistreatment she’s faced as a woman, sees the transformation as an opportunity to obtain things she’s always wanted. Elizabeth is more confident and accomplished than Eli and, in his body, she’s able to pursue a life that didn’t previously seem available to her. In contrast, Eli’s gendered experience, as a woman, is as much about being a woman–for instance, when going out with a bartender in Paris–as it is about being a particular woman, Elizabeth. He attempts to imitate the competence she showed, at times becoming a better version of himself because he’s living as her.

4. At one point in the novel, Eli narrates, “We didn’t have sex as often as she [Elizabeth] liked, and her ability to predict my desires and needs embarrassed me. I did not like to be known. I preferred to be misunderstood and cryptic, like an inkblot or a footprint on a carpet.” That tension between being seen and known by a romantic partner and the desire to be somewhat obscured to them is a thread running through the relationships in People Collide. What drew you to exploring that tension?

I feel like this is one of the scariest things about intimacy—that another person might know you as well or better than you know yourself. It can be frightful to allow another person in so deeply, I feel, and Eli is someone who both craves and resists that intimacy. Being known can feel like a loss of autonomy. It’s something I’ve had to work through in past relationships, and the novel seemed like an excellent way to work through what is desirable about both. Because it can feel amazing to be taken care of, to be known, but it can also feel limiting if one is shown things about oneself that are difficult to confront. Eli is still discovering a lot about himself. And at times, Elizabeth’s awareness can feel like a restriction. He wants to believe he is more unpredictable and unique than he is. But what he often doesn’t realize is that however predictable he may be to her, she is just as predictable to him—the reader discovers this by viewing his attempts to perform as her.

“No book will ever present an objective truth, even when it tries, and I like when readers are given space to fill in narrative gaps.“

5. The novel is primarily told in first person from Eli’s point of view, but occasionally a chapter is told from the point of view of an omniscient narrator and, near the book’s end, from the perspective of Elizabeth’s mother, Johanna. However, the book is never told from Elizabeth’s point of view. What led to this artistic choice? How did the different narrative points of view allow you to reveal or conceal different parts of the story?

There’s another version of the book where both characters are granted equal narrative space, but that wasn’t the book I wished to write. I think it could have been interesting to move in that direction. However, I’m fascinated by how narratives are created out of limitations. The reader only gets Elizabeth’s perspective through Eli’s narration. That forces them to either trust Eli or to question his narrative. And this is where narrative can become really exciting. No book will ever present an objective truth, even when it tries, and I like when readers are given space to fill in narrative gaps. Elizabeth doesn’t tell Eli everything she does in his body, so the reader doesn’t know either. This speaks to the questions of intimacy at the center of the book. Just as the reader doesn’t gain access to Elizabeth’s POV, Eli can never really know her, no matter how intimate they are.

6. A particularly memorable and richly layered scene in the novel is Eli-as-Elizabeth and Elizabeth-as-Eli having sex in the Pompidou in Paris: “‘Keep looking at me,’ she said. I would’ve felt like a misogynist for saying this to her, but I loved hearing it, as if it were the voice of my own desire cleansed of all inhibitions.” There are so many elements at play in the scene–their knowledge of how the other’s body experiences pleasure, how they experience pleasure in each other’s bodies, how they pleasure their former bodies, what it means to have sex with your former sex as a new sex. How did you approach weaving in these elements of characterization, plot, dialogue, gender dynamics, and sexual dynamics with erotic description?

The most important thing in that scene was maintaining a visual on the characters. When I first wrote it, I tried to focus on where each person was spatially in relationship to each other. Once I figured that out, I was able to move deeper into the thematic elements of the scene, the bigger picture questions about characterization and sexual dynamics. But it seemed to come fairly intuitively, and I think this is because of all the character work that appears in the previous scene. The dialogue of the earlier moment, when Eli and Elizabeth are walking through the Pompidou, sets the foundation for the dialogue in the bathroom. It’s as if they’re continuing the conversation, albeit physically. I also wanted to focus on the excitement and surprise of the moment for each person. For all the technical and craft work that went into the scene, I don’t think it would work if there weren’t elements of surprise and novelty for Eli and Elizabeth.

7. In discussing his former body and seeing it in action removed from his embodied experience of it, Eli-as-Elizabeth is able to reflect upon his body dysmorphia. It is rare to see literary novels look at men’s experience of body dysmorphic disorder. Was it a decision to bring this element into the novel or was it something that sprung naturally from the creation of Eli as a character?

It wasn’t a very conscious decision, as in I didn’t set out to highlight a man with body dysmorphic disorder. It did emerge naturally out of Eli’s character—he is someone who went through dramatic physical changes over the course of his life. But one of the main symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder can be the failure to see oneself objectively or sympathetically. Though I don’t see this moment as a kind of cure for Eli, he is granted a perspective that seems special and rare. It’s a gift. And him having this disorder makes that moment of perspective especially affirming and disorienting for him. Eli was always suspicious of Elizabeth’s praise, but in that scene he can see she might have been honest when complimenting him. The moment wouldn’t have been so powerful, I don’t think, if Eli didn’t feel about his body the way that he does.

8. What do you want readers to take away from People Collide?

I want readers to think more deeply about their connections to those closest to them. This is a book about compassion, and empathy, and about how well we can ever know the people in our lives. My goal is for readers to see those connections in a new light, to consider the paradox of closeness and separation. It would also be great if they laughed at the jokes in the book.

“This is a book about compassion, and empathy, and about how well we can ever know the people in our lives. My goal is for readers to see those connections in a new light, to consider the paradox of closeness and separation.“

9. What’s a piece of art (literary or not) that moves you and mobilizes your work?

A few weeks ago, I saw Pamela Z’s Simultaneous at the MoMA, and I doubt a day has gone by when I haven’t thought about it. It’s an intermedia chamber piece featuring recordings, electronic processing, and vocal performances. Mostly, though, it’s a love letter to sound and narrative and the human voice. I saw it twice in four days. The piece made me reconsider how I wanted to engage with dialogue and patterning in novels. There is something deeply intelligent and moving about it, something so full of love for how people communicate. Few things have ever made me want to make art so badly.

10. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

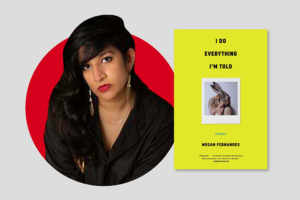

So many writers! I’m a huge fan of Catherine Lacey, Jamie Hood, Alexandra Kleeman, Katie Kitamura, Megan Fernandes, Edgar Kunz, Sarah Thankam Mathews, John Manuel Arias, Gina Chung, Ruth Madievsky, Maya Binyam, Jenny Xie, Shola Von Reinhold, Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi, Novuyo Rosa Tshuma, Sabrina Imbler, Edgar Gomez, Elaine Hsieh Chou, Chantal Johnson–I wish I could go on forever!

Isle McElroy (they/them) is a non-binary author based in New York. Their writing has appeared in the New York Times, The Atlantic, New York Times Magazine, The Cut, GQ, The Guardian, Vogue, Bon Appétit, and other publications. They have received fellowships from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Tin House Summer Workshop, the Sewanee Writers Conference, and they were named one of The Strand’s 30 Writers to Watch. In May 2021, Isle founded Debuts & Redos, a reading series for authors who published books during the pandemic. Their first novel, The Atmospherians, was named an Editor’s Choice by the New York Times and a book of the year by Esquire, Electric Literature, Debutiful, and many other outlets.

Sam Sax | The PEN Ten Interview

I think in that same way that every poem teaches you how to read it, every poem you make teaches you how to make it as you’re writing.

Sola Mahfouz & Malaina Kapoor | The PEN Ten Interview

In Afghanistan, laughter is as much a part of life as sorrow and pain. People crack jokes while hiding from bombs in basements, finding humor in their grim reality.

Jillian Tamaki & Mariko Tamaki | The PEN Ten Interview

Your first big break up, the first loves of your life, are your friends. Those stories are really interesting, meaty stories.

Megan Fernandes | The PEN Ten Interview

My focus was just on the insecurity of being. Everything that happened narratively came from focusing on that feeling as much as possible.