Librarianship extends far beyond library shelves, and even further beyond the covers of books. Librarians are trained to respond to curiosity. While they may not know the answer to a question, they tell us where to go in search of an answer or how to go about research towards one.

But responding to the research needs of people who are incarcerated requires a bit more focused attention. While people on the outside use a search engine as an initial step to find information, people in prison have no internet to do this on their own. With the rise of banned books and carceral censorship measures, librarians have to be resourceful with how they get information to people in prison who have limited means of communicating outside of their facilities and little to no access to a diversity of useful books.

The Prison Library Support Network (PLSN) was launched in 2015 as a structured group of volunteers working with public librarians to provide remote reference services for people in New York City-area jails and prisons. In this interview with Malcolm Tariq, senior editorial manager for PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program, PLSN coordinators Manuela Aronofsky and Mia Bruner discuss the process of receiving and answering reference letters, and the challenges volunteer groups encounter operating such a vital service.

A few months ago, we spoke with Brooklyn Public Library’s Justice Initiatives Program about the services they offer to people in prison in New York City. I’m sure as librarians you are familiar with how the city’s public libraries work with prisons. Can you tell us a bit about how the Prison Library Support Network got started? In your experience, how does your work differ from what libraries have traditionally offered?

The biggest difference is that PLSN doesn’t work within an institution – meaning we don’t have to answer to a larger entity that could restrict our ability to do abolitionist work. This is unlike the New York City library systems which are accountable to the DOC (Department of Corrections) as a municipal partner. We answer to the incarcerated people who we are trying to show solidarity to and we hope to keep it that way!

PLSN started as a group that aimed to support existing library services to incarcerated people. This included Brooklyn Public Library and the other NYC library systems. We both attended Pratt’s School of Information for our Library Science Masters, and in one class we had an assignment to respond to a reference request from an incarcerated person. The letters were supplied to Pratt students by New York Public Library’s Correctional Services librarians. We enjoyed the work and were curious as to how we could keep doing similar letter answering on our own. This is how we learned that there was no formal volunteer base working with the library systems to tackle the backlog of reference requests. We formed a collective to host the first reference project we conjured up, which used letters from the Brooklyn Public Library’s backlog.

I’ve heard you speak about reference letters before, and I am fascinated by the scope of this work. At PEN America, we are familiar with people writing from prison to request our handbook, The Sentences That Create Us, and other information about our annual PEN Prison Writing Awards and the PEN Prison and Justice Writing Mentorship Program. But, we unfortunately don’t have the capacity to fulfill other requests. Can you explain what a reference letter is and the process of responding to questions? What have you learned in your experience answering letters, or what has been the most memorable letter you’ve responded to in recent years?

We’ll start with what the word “reference” means in librarianship terms. Reference in libraries typically is understood as a personal assistance to library users seeking information. Researchers might come to ask a librarian for support at a desk, or via email, phone, or even chat. In a reference exchange, the goal of a librarian is to act as an intermediary between someone with a question they can’t answer and information resources that might help. In most cases, we aren’t engaging in the actual research for people but offering materials or search strategies that support the researcher looking for answers themselves. Something really important in conventional reference is this idea of the reference interview. This is basically a casual exchange where a librarian asks clarifying questions to better understand the question on the terms of the person asking. The prison industrial complex effectively imposes a barrier on this process making it impossible for the researcher to share their expertise in defining their own needs.

A reference letter in the context of our project is a physical letter that an incarcerated person writes to PLSN. The letter includes a request for research assistance. These research questions range from re-entry and legal questions, to asks for tabletop game manuals, sports scores, song lyrics, and more. The questions really range and it is impossible to define an exact scope. We’ve developed a way for each letter to be securely scanned and uploaded, and then sent out to our reference listserv for a volunteer to claim and answer. One of the things we’ve learned through this project is how important it is for people to autonomously choose what they’re learning about, and how violent it is for the prison industrial complex to limit this access to information it deems acceptable for those inside.

Like we said, there have been such a range of questions, and so many memorable letters that it is hard to choose just one. We’ll name a few here that stand out:

- A letter asking for advice on setting boundaries with parents

- A letter asking for a matching parent-child Pikachu hat crochet patterns

- A letter asking for archival news clippings reporting on Seneca Village

What are some of the challenges you encounter in your work with PLSN?

The incredible need created by prisons has become only more apparent through our work. The biggest challenge has been realizing how badly our reference service was needed, and having to pause intake of letters to ensure the integrity of our program. Only 14 of 50 states offer a reference-by-mail service for incarcerated people, and because of this we began receiving thousands of letters from people all over the US. Our priority has always been remaining reliable and accountable to the people writing to us. Because we weren’t able to keep up with the processing and answering of these letters in a way that we felt was sustainable, we paused our service to address the backlog. While our next challenge will be tackling how best to restart the project in a way that aligns with our standards, we can say that our backlog is thankfully down to less than 350 letters.

This seems like it might be common for organizations who field requests from people in prison. There is always a high demand for information from inside prison, but staffing capacity is not always consistent with the rate of requests. How do you train volunteers and what are some things they work on with PLSN? Do you accept remote volunteers who are not based in New York City?

A few years ago, we realized that we needed a systematic way to onboard new volunteers to our network. We regularly receive many inquiries via email as to how new folks can get involved with PLSN but don’t have full time staff who can address these questions individually in an ongoing way. Our solution was to try to establish two monthly time slots for new volunteer onboarding:

- Regular general onboarding sessions, where we provide 30 minutes worth of information about PLSN’s history, mission, current projects, and ways to get involved. These occur virtually (almost) every first Sunday of the month. Once volunteers attend this session, they can decide the capacity to which they want to volunteer with PLSN.

- Regular reference-specific orientations, which also still happen primarily over Zoom. Most of our new volunteer inquiries are about our reference project, so we’re really happy that we have a superstar designated training team that facilitates these sessions. Once volunteers complete the reference training, they are signed up for our reference-specific listserv and can begin claiming reference letters to answer.

PLSN volunteers do not need to be librarians or information professionals! Our volunteers contribute in various ways, bringing a wide range of skills to the table. These contributions encompass tasks that go beyond the traditional scope of librarianship, such as copyediting, project planning, fundraising, and logo design. They also include activities typically associated with libraries, such as offering research support, creating reference guidelines, and hosting events with librarian-led organizations.

Since PLSN operates as a mutual aid-based, community-driven project without any paid staff, every aspect of PLSN has been developed by members of our volunteer collective. New volunteers will typically jump onto existing projects like our reference letter service (either attending a volunteer orientation to answer letters, or an organizing meeting to get involved in sustaining and shaping the project) but we always try to make sure there’s space to propose new projects or collaborations too. And as most of our volunteer work (especially reference) can occur remotely, we definitely accept and train volunteers who are not based in NYC.

There is a set of foundational principles that governs how PLSN ethically advances its mission. Why was it important for you to name these principles, and have these changed over time? I am particularly interested in “No cops, no saviors,” if you can speak about that.

Librarianship is a field with a long history in white supremacy and an entrenched bond to the colonial state. In order to envision an approach to this work that pushes back on that, it felt critical to have clear values guiding our work. “No cops/no saviors” refers to our belief that rather than deciding what’s best for people, we believe people know best what they need. We approach reference with the goal of responding to stated needs by offering people the best information possible to do what they feel is in their best interest. Apart from following mail policies from the DOC, we reject the idea of imposing judgments on what is safe to share and we don’t believe in creating hierarchies about what’s virtuous or appropriate to ask for. This is a break from models typically used in libraries and is just one example of how our reference project has demanded new and explicitly abolitionist approaches to sharing information.

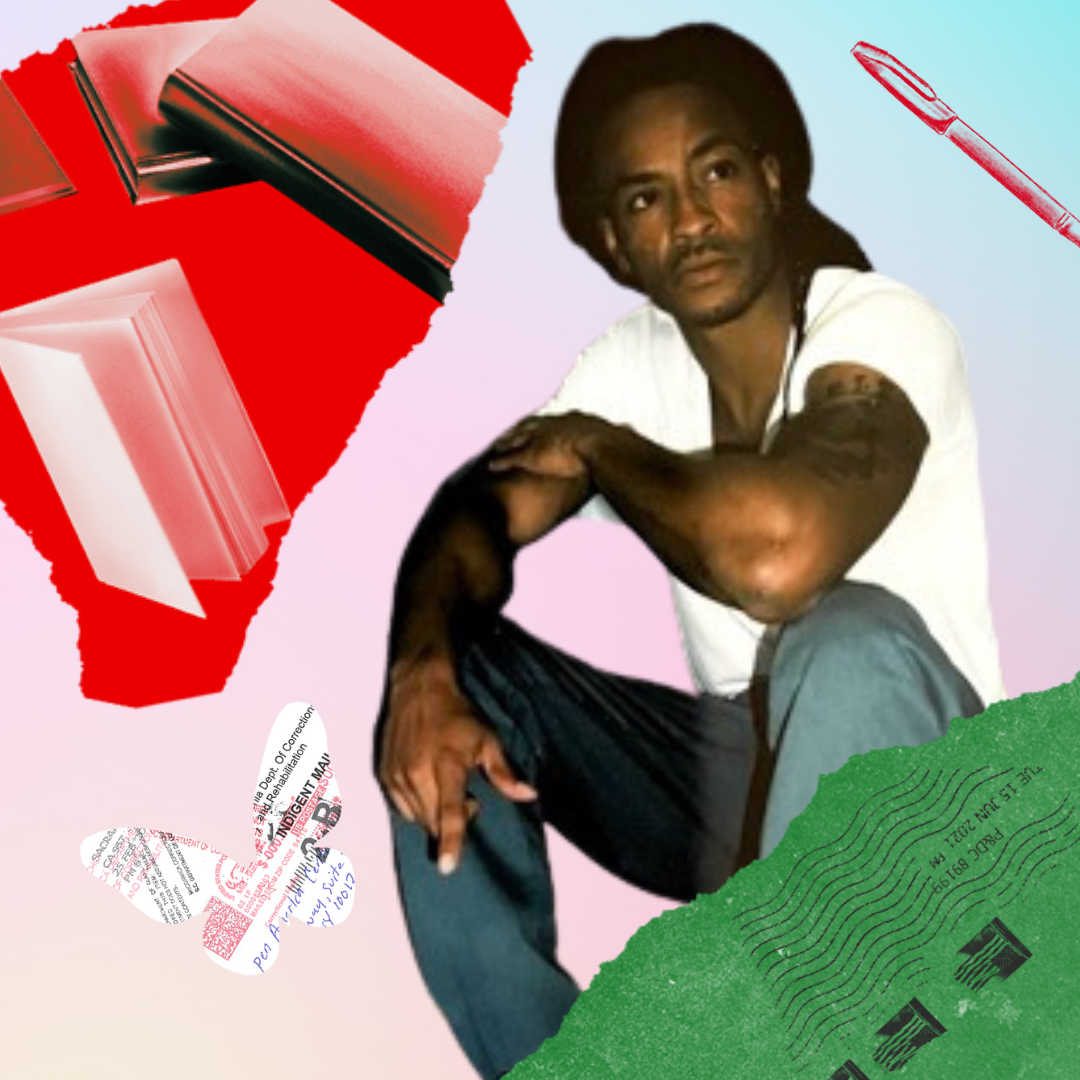

Public programs and events help community members get informed about carceral practices and injustices, and get engaged with local efforts to serve vulnerable communities even if they cannot commit to a long term volunteer initiative. Recently, Manuela’s exhibition space, Lunita Loft, closed I Refuse To Remain Silent…, a solo exhibit of work The Steven Levy system, an incarcerated queer/trans artist in California. How was this experience and what other public programs have you produced?

The opportunity to showcase Steven / Shelly’s powerful artwork and artist statement has been a really special experience. The art show was built around a relationship PLSN has with the Bay Area’s A.B.O. Comix, one employee of which has been a remote PLSN volunteer for many years. A.B.O. has a penpal program which Steven / Shelly is a part of. The ability to put this art show and fundraiser on is just one amazing example of how PLSN’s network has expanded in really fulfilling, tangible ways. Installing and viewing the artist’s detailed collage work and paintings that were all created with limited materials found inside San Quentin has been a moving experience for everyone who has been involved. By the way, you can donate directly to the artist’s commissary fund via the A.B.O. Comix Venmo.

We’ve done many other public events and programs – mainly panels where we have talked about our work to various audiences, as well as different donation drives. We also host our quarterly abolitionist discussion group, which is a great way to join in conversation and learn about abolitionist topics by engaging with different mediums (books, podcasts, videos, etc.).

One other successful event we like to highlight is a one-off project we did that involved cleaning up and lightly remodeling the room of a Brooklyn Public Library branch that is used for video conferencing with incarcerated folks. It was effectively a storage closet before PLSN spent an afternoon working in it, and after the volunteer effort it became a much more comfortable and inviting space for families and young children to be in while communicating with incarcerated loved ones.

Does PLSN have any upcoming projects or events? What’s in store for the organization?

We’re glad you asked this, because it’s a great place to promote joining our general listserv! You can do this by sending an email to: [email protected], which will automatically subscribe you. Once you’ve subscribed you’ll receive our monthly PLSN newsletter, which is quite honestly the best way to see what events are happening each month. Besides a calendar of events, we have sections of our newsletter for project updates, abolitionist actions to support, and (one of our favorite parts) a “From the Network” section where volunteers can send us events and initiatives they’d like to promote to our list.

Since we’re winding down our art show, we currently just have our regular meetings, trainings, and discussion groups on the horizon. However, we are still in need of reference volunteers who can volunteer their time by continuing to work through our letter backlog. If anyone is interested in being onboarded to the reference project ASAP, we suggest they join an upcoming reference training and then any of our monthly reference meetings to hear updates on how we plan to restart an intake of letters. As far as what’s in store – our biggest priority is continuing to keep our reference project sustainable, and collectively sharing as much information as we can with people inside.

Malcolm Tariq is the senior editorial manager for PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing program. His collection, Heed the Hollow (Graywolf Press, 2019), is the recipient of the Cave Canem Poetry Prize and the Georgia Author of the Year Award in Poetry.

Manuela Aronofsky is the Middle School Technology Integrator at a middle school in Brooklyn – she loves being a bridge between tech + library worlds. Originally from Missoula, Montana, Manuela earned her M.S. in Library and Information Science from Pratt Institute in 2019 with a concentration in Youth, Literacy, and Outreach. She has been a central organizer with PLSN for many years.

Mia Bruner is a reference librarian at the New York Public Library and founding member of the Prison Library Support Network. Her work focuses on the radical potential of reference and the capacity of library workers to support movements for prison abolition.