Injuries Incompatible with Life

Ryan M. Moser was awarded honorable mention in Essay in the 2020 Prison Writing Contest.

Every year, hundreds of imprisoned people from around the country submit poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and dramatic works to PEN America’s Prison Writing Contest, one of the few outlets of free expression for the country’s incarcerated population.

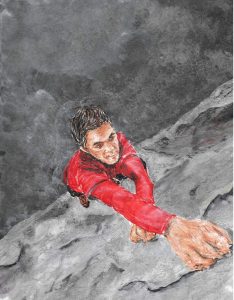

The illustration for this piece of writing was expressly created by an incarcerated artist curated by Justice Arts Coalition. This piece is also featured in Breathe Into the Ground, the 2020 Prison Writing Awards Anthology.

INJURIES INCOMPATIBLE WITH LIFE

Image by Jeremiah Murphy

The police car sits idle on the shoulder of I-95 with its headlights beaming through the lavender mist of an evanescent dusk, reflecting off the wet macadam as I explain my predicament. After a few minutes, the broad-shouldered state trooper shows mercy and drives me to the Jacksonville Memorial Hospital so I don’t have to hitchhike with a “medical emergency,” and I grab my abdomen the entire 15-minute ride, faking my symptoms like a professional actor.

“Yeah, I’m vomiting. And my stomach hurts. Like a burning, sharp pain,” I tell the intake nurse as she checks my vital signs. “No ma’am, I’ve never had stomach pains like this before.” I clutch my right side as if I’m holding my intestines in after a knife fight, not sure if my ruse is working. When she lightly touches my obliques with her finger, I decide to go for the Academy Award. “Oww! That hurts really bad.”

“Oh dear, I apologize,” the woman says in a Southern accent. “You sit right here, sugar, and I’m gonna get a doctor to have a look at you.”

Opium is a narcotic drug produced from the drying resin of unripe capsules of the opium poppy: Papaver somniferum. Grown mainly in Afghanistan and Myanmar, the legitimate world demand for opium amounts to about 700 metric tons a year, but many times that amount is distributed illegally.

I’m nauseous and sweating profusely, and the hot/cold chills are almost unbearable, but I don’t need a professional to tell me what’s wrong: I haven’t had a Roxy or a Vicodin since yesterday morning. I know from experience that when I go eight hours without painkillers, I start to get cranky and anxious. After 12 hours: flu-like symptoms. Twenty-four hours: desperation, restless leg syndrome, diarrhea, and shakes that consume my existence until (a) I score some pills or (b) five days can pass to detoxify my system.

The emergency room smells like antiseptic and is full of activity. I spend 10 minutes in the bathroom with the runs and then sit on a padded hospital bed covered with tissue paper, awaiting some relief: a compassionate nurse who feeds me a codeine pill to ease my suffering, a stern doctor who warns me not to come back as he gives me a Lortab, an impatient and overworked resident that writes a small script for Percocet to get me out of his hair. I’ve played this game three times with the local hospitals and each time I’ve won, but as the attending physician walks into the room, I have a foreboding sense that he is all business.

“What concerns me is the location of the pain, Mr. Moser.” The doctor is a handsome Middle Eastern man with a hairy chest poking out from the blue Oxford under his lab coat and chewing gum on his breath. “Severe abdominal distress of this nature is very serious, and I’m concerned that you could have an inflamed appendix. Typical symptoms are fever, vomiting, nausea. I’d like to do an ultrasound image and go from there.”

“Um… okay. Whatever you say, doctor.” I haven’t eaten or slept and I’m dehydrated; it takes all of my skills of manipulation to ask my next question sincerely and not raise any suspicion. “Do you think I can have some water and something for the pain?”

The erudite healer looks up from my chart in an aloof manner and turns to leave. “Not until we know if you need surgery.”

My hopes drop. What can I do to exploit him? I’m not leaving without something, no goddamn way. I can’t go through another night of this agony. I don’t want to lie in a pool of sweat on a bare mattress, replaying my mistakes over and over in my mind like a highlight reel on ESPN. Failed relationships… lost jobs… unpaid bills… near arrests… bad parenting. I look around the emergency room and fantasize about the pharmaceutical treasure trove hidden behind a Plexiglas cage somewhere not far from me, sinking into despair at the thought of leaving empty-handed. I’m adrift in a sea of misery with no land in sight and ready to drown.

Opiates first produce a feeling of pleasure and euphoria, but with their continued use, tolerance is built up and the body demands larger amounts to reach the same sense of well being. Withdrawal is extremely grueling, and addicts typically continue taking the drug to avoid “dope sickness” and to attain the initial state of euphoria. Symptoms of withdrawal from opioids include kicking movements in the legs, anxiety, insomnia, nausea, sweating, cramps, vomiting, diarrhea, and fever.

A petite general surgeon stands next to the attending physician, examining my ultrasound film like a Monet painting, twisting and turning it, pointing at the suspect in question: my appendix — the only organ with no known function in humans. After a brief and methodical study of the Rorschach inkblot test that is my internal anatomy, the puzzle of my ailment is surprisingly solved.

“You have appendicitis,” the surgeon states frankly. She is unremarkable and plain, an older woman with faded brown hair tucked into a bun and boring glasses. She clicks her pen and consults the ultrasound once more before showing me the evidence of my body’s supposed treachery. Bewildered, I stop writhing in dramatic fashion just long enough to ask her to repeat herself. “This darkened area here shows an inflammation of your appendix, and we need to perform an emergency appendectomy. The surgery itself is routine, but necessary. In your case, with the amount of pain you’re experiencing, I recommend we operate now, Mr. Moser. Recovery time is about three weeks, during which you will be properly medicated and receive some follow-up treatment to remove the surgical staples.”

The attending physician holds a legal document in front of my face, clearly not happy about having an uninsured patient in his E.R. “We’re not legally allowed to turn away any emergency surgeries. This will absolve the hospital of neglect and a bill will be sent to you for the cost of operation.”

Because of opium, America is facing its most serious drug epidemic in the history of our nation; a public health crisis so devastating that it has forced a paradigm shift on addiction, and is changing our ideas about disease and modern medicine. In addition to record-high overdoses, taxpayers are burdened by overcrowded prisons, hospitals are inundated with drug-related admissions, families are being torn apart, and many communities are now ravaged by the effects of opioids. Opiate dependence is a physical and habitual compulsion that doesn’t discriminate between race, class, age, or gender.

My stomach turns and I wipe sweat from my brow. I watch the doctors watch me, waiting for an answer. A simple transaction: one appendix for 100 Oxycontin. I feel like a slimy clam withering around inside its shell. All I want is to get rid of this unbearable monster devouring my soul, and at this very second, I will do almost anything to have the chills go away. I can no longer contain my retching and shaking from withdrawal. I’m in full crisis mode and need immediate help. Things are now officially out of control; I realize that if I choose to follow this trail of madness, this charade, that the humiliation will follow me forever. The gravity of such a mistake will weigh on my conscience every time I look down at the pale-pink scars, and I know I’m about to cross a line of degeneracy. But I don’t care. The only thing that matters is relief, so I text my mom a cryptic message about minor surgery and sigh.

I can’t really formulate a rational sentence; I simply sign the paperwork and curl up in a ball on the bed as the E.R. nurses prepare a gurney to take me to the operating room. I’m rolled to a pre-op area on another floor and ache with anticipation for the morphine that will soon be flowing into my vein from an intravenous line, trickling down a tube like hypnotic nectar from the gods. I’m given a gown to change into and some more paperwork to sign, and I write down a fake address while the surgeon tells me how lucky I am to catch this early. “If the appendix wall ruptures, infection will spread to the abdominal cavity, causing peritonitis. Oftentimes this can be fatal, so this is an urgent procedure.” When she leaves to scrub in, a new face joins my bedside with a series of shots to my trembling forearm.

“You may feel a little groggy and confused when you wake up from the anesthesia — that’s typical. I’ll be monitoring your vitals and all that. You’ll be fine, dude.” The anesthesiologist is a hip Spanish guy in his forties wearing multicolored scrubs and a bandana, and he has an especially cavalier attitude for someone who could legally kill me and not be charged. All I want at this moment is to be knocked out so it can start — the sooner I wake up, the sooner I can feel the comforting warmth and euphoria of a painkiller drip. I’m oddly at ease as the surgeon reappears wearing medical scrubs, a mask, and gloves; the last thing I remember before going under is the cold air-conditioning on my stomach as a nurse opens up my gown and the bitter smell of iodine…

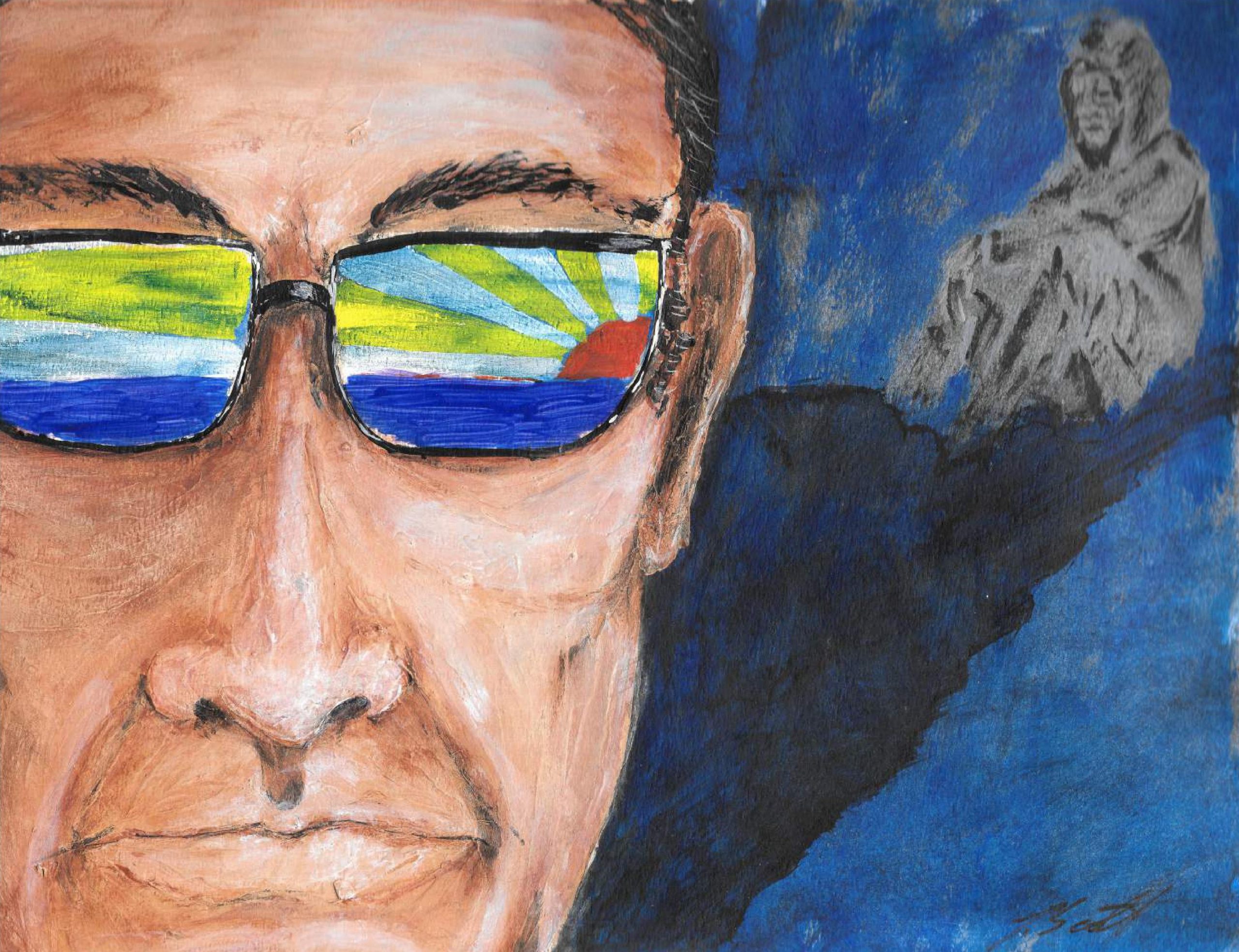

Image by Jeremiah Murphy

For thousands of years, opium has been used as healing medicine and a folk remedy. When opium smoking was introduced in China in the 1600s, serious addiction problems arose. In the 18th century, opium made its way to Europe and North America, where addiction grew out of its prevalent use as a painkiller. With the invention of the hypodermic syringe during the American Civil War, the injection of morphine became indispensable in treating patients who had to undergo some of the newly developed surgical operations — including innumerable amputations. Physicians of that time hoped that injecting morphine directly into the bloodstream would avoid the addictive effects of smoking or eating opium, but instead it proved more addictive. With the discovery of heroin in 1898 came a similar hope, but this more potent drug created a much stronger dependency than opium or morphine. In 2018, it was estimated that over three million Americans were addicted to heroin and other opium-based products.

“Do you know what your name is?” I hear the faint sound of fingers snapping in the distance of my dream-state and slowly open my eyes. “What’s your name?”

“Huh… um… Ryyyan.” I lick my dry lips. “It’s… I’m… Ryan.”

“Good. You’re in the hospital, mi amigo. How do you feel?” The anesthesiologist waves a pen flashlight in front of my eyes and pinches my thigh.

“Ouch. I’m uh… really good. I feel high,” I spurt out reflexively. My mind is clouded but I sense my dope sickness is over, and I see the doctors and nurses around my bed are in urgent motion, tending to my abdomen and fixing the I.V. lines and sensors. Monitors beep incessantly around me. I’m relaxed but incoherent, and as I fade back into unconsciousness, I hear an official voice instructing the nurses to watch me closely because I’m an “at-risk patient.”

Although the synthetic narcotics methadone and Suboxone have been used to offer addicts some relief from withdrawal, they are an addictive substitute, and complete recovery requires years of social, physical, and psychological rehabilitation.

The emergency room doctor from my intake is checking my pulse unsympathetically as I suck water through a straw. I’ve only been awake for a minute, but I see bright sunlight peeking through the curtains and wonder how long I’ve been sedated. “What time is it?”

“Four o’clock. You’ve been asleep for some time. Dr. Walsh is the surgeon who operated on you, and she’ll do your follow-ups. The surgery went well and you’ll recuperate fine. However, I’m very concerned about your personal welfare, young man.” He puts my chart away and stares at me intently. “Mr. Moser, did you know that hospitals share information about psychiatric patients on a state-wide database? In the last month alone, you’ve been held under the Baker Act two times for suicidal tendencies. And upon further inquiry, it turns out that you’ve visited all the area hospital emergency rooms recently. Would you care to elucidate?”

The Baker Act is a Florida law which allows family members to involuntarily commit someone for a 72-hour period if they are a danger to themselves or others. In my case, I self-committed under the guise of hurting myself in an effort to get off drugs. Twice in one week. The urbane doctor’s question catches me off guard so thoroughly, and I’m so stoned, that I’m just outright honest.

“I’m a pill head. And I started smoking crack this month — I just can’t stop.” I pause to drink more water and wipe a tear from my cheek. “My girlfriend left me and I lost my job. I don’t know what to do. I’m homeless and hooked on drugs.” I turn away from him and a shooting pain sears my abs, prompting the physician to look at my staples.

“That explains your high tolerance for morphine.” He takes his glasses off and leans very close to my bedside, earnestly analyzing my facial clues for trustworthiness. “Did you admit yourself to my hospital under false pretenses to get prescription pain medication?”

I don’t answer him. I wonder if I’ll eventually die from this disease — my anathema. I lie in bed staring at the wall in embarrassment, afraid of the repercussions of my duplicity. I know that I can’t really get in any trouble for what I did, but understand that if I say the truth aloud it will make this a real and tangible horror story about my addiction, not a footnote. Admitting my fraudulence to this judgmental man will carve the problem in marble like a Rodin sculpture, on display for all eternity. I weep in silence as he shakes his head slowly, pinching the bridge of his aquiline nose while acknowledging a grim reality: “His hospital” made a critical mistake and performed unnecessary surgery on a pill-seeking junkie. An $18,000 mistake, considering I wasn’t going to pay the bill. After a tense moment, the contrite doctor stands to leave, wordlessly confirming our secret collusion. I guess he knows there’s nothing to be done now except focus on my recovery, and the truth will only cause more harm than good for all.

According to the mortality rates from the National Center for Health Statistics, more Americans died from accidental drug overdoses in 2018 than from car accidents. Over 59,000 people lost their lives because of a treatable addiction to opioids. The discovery of a class of compounds that are specific antagonists to the action of the opiates has made it possible to treat opiate overdoses quickly and efficiently. The standard drug for this use is Naloxone. School nurses and first responders have been trained to administer Naloxone to combat overdoses, and “safe injection sites” are springing up in forward-thinking cities all over the country.

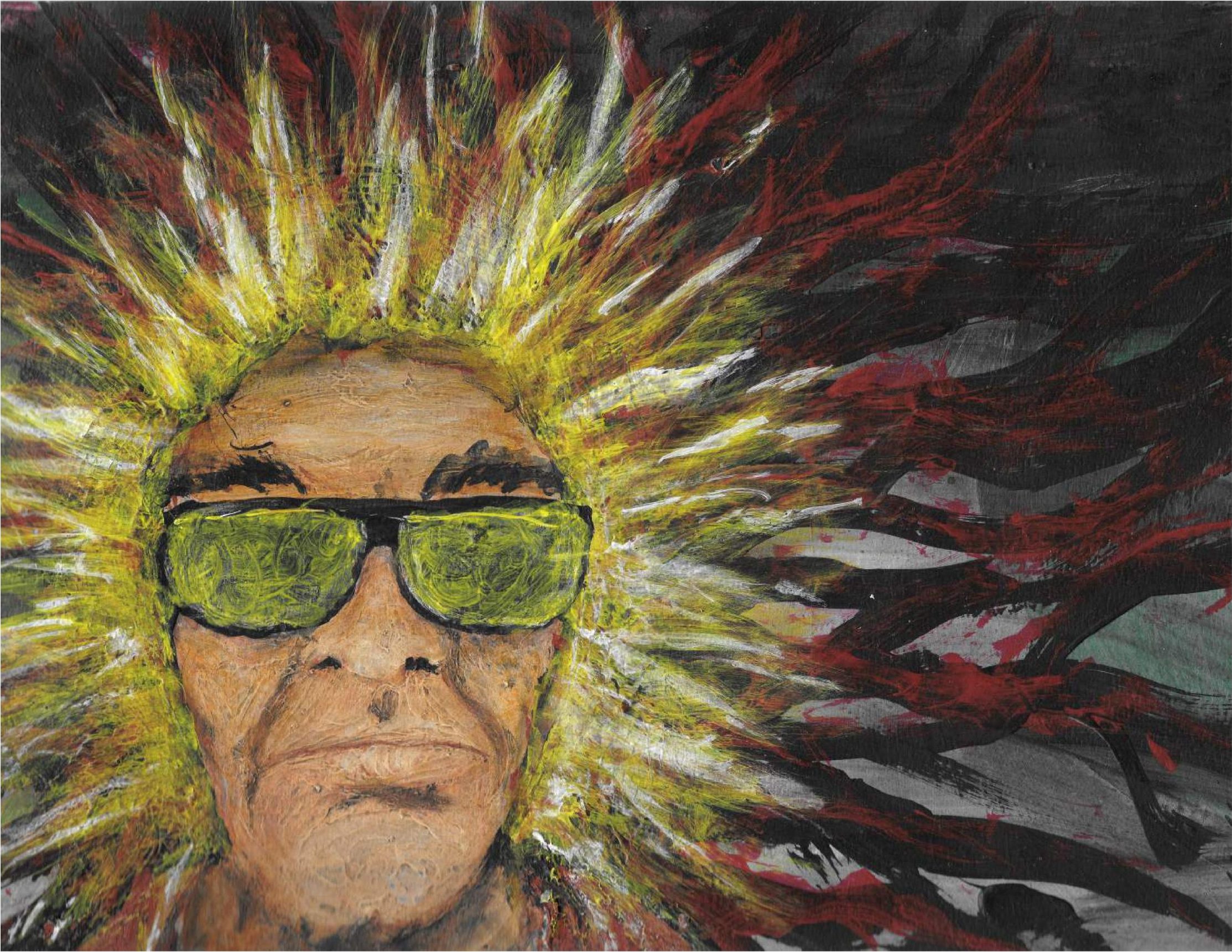

Image by Jeremiah Murphy

When I wake back up, it’s nighttime and there’s an attractive blonde nurse hovering around my bed, checking on me like a concerned aunt. I’m aware of her movements, but all I can manage is a slight smile while I ask about food. After neglecting basic needs like sleep, food, and water for days, my body is screaming to catch back up.

“Sure thing. How ’bout some meatloaf and taters? Do you like Sprite?” She tucks the blanket under my cold feet and pats my leg.

“Yes ma’am.”

The 40-professional huffs jokingly. “Do not call me ‘ma’am.’ You can call me Stacy, darlino.”

I turn on the television and put the remote on the tray table. “Okay, I’m Ryan. Where are my clothes? I need my cell and smokes.”

The nurse grabs my pants from a closet and pulls out my phone. “There’s a charger plugged in next to your bed. Sorry, no smoking for you until you can walk outdoors. I’ll be back soon with some grub, so you just relax.”

“Thanks, Stacy. You know, you’re very pretty,” I add, trying to be charming.

“Well, thanks. Oh, your phone’s been ringin’ a lot, you should check your messages.”

When she leaves, I look at my cell and see that I have over 30 texts and missed calls — most from my dealers or ex-girlfriends, and several from my mother. I remember the message I sent to her before surgery and cringe — she must be more worried than usual, if that’s possible. My family has been on the roller coaster ride of my addictions for years, and they already know I’ve lost everything over the past few months of debauchery. I’m ashamed now that the withdrawals are gone and I’m lucid. I second-guess my decision — the abnormal subterfuge that fed my demon. I don’t want to talk to her, but I know that I have to.

The molecules of opiates have painkilling properties similar to those of compounds called endorphins produced in the pituitary gland. Being of similar structure, the opiate molecules occupy many of the same nerve-receptor sites and bring on the same analgesic/euphoric effect as the body’s natural painkillers. The mode of action of the narcotic analgesics is still not fully understood, but recent research has determined that specific regions of the brain and spinal cord have an affinity for binding opiates, and the binding sites in the brain are in the same general areas where pain centers are believed to be. This research has also succeeded in isolating compounds, called enkephalins, which are produced in the body to reduce pain: administration of endorphins, including the enkephalins, results in effects similar to those produced by opiates.

The phone call is excruciating. Hearing my concerned mother fret over a self-inflicted injury brings me to a new low; maybe this is the rock bottom everyone talks about. I’m so feeble-minded, allowing a tiny pill to lead me into situations of such vulnerability. I’ve compromised my integrity, family, self respect, to get what I crave. I’ve sold everything I own of value. I pull the sheets over my head and search my foggy mind for an explanation of this insanity. In the last few months, I’ve tried committing myself to a mental health clinic, paid for a weekend treatment center, begged my ex for help, and told my family about my problem, but nothing has worked.

When I was eight and innocent and unbound by the troubles of adulthood, I never saw my future self as a hostage to an enemy like this, losing in battle against a temporary high. I wanted to be a fighter pilot or an author or a prince — not a destitute drug addict doing anything to come up. How the fuck did my life come to this at 34? I used to have a hot wife and a new sports car and an important job, but if those things really matter in life, why wasn’t I happy when I had them? Why use drugs? What caused me to start spiraling down the rabbit hole and give up everything I’d worked for? What is it about my personality that clings to drugs like an octopus wrapping its tentacles around a hapless clownfish?

A popular scientific theory states that people with a natural deficiency of endorphins and other chemical compounds can become more at risk for opioid addiction than others.

When the morphine drip is suspended, I’m given Percocet orally that I “cheek” and save for later because I need a higher dosage than the hospital will give me. I store the 10-milligram pills up to take them all at once later. In order to combat the physical pain without any Percs in my system, I beg for morphine until a doctor comes to see me. When she wavers, I threaten to check myself out of the hospital against orders and the physician concedes to my childish tantrum, feeding me a steady I.V. of dope once again. The nurses, doctors, and employees all know I’m an addict, and acquiesce to my demands of extra food and pain medication, albeit with pity bordering on repugnance. They ignore the infraction when I smoke a cigarette in the bathroom and take me in a wheelchair down to a patio to appease my nic fits. Nurse Stacy treats me with compassion and laughs cheerily when I repeatedly ask her out, but is blunt about my prospects; I fear that she has seen many people in my position and has me pegged. When I walk out of the hospital I will have an enormous amount of pain pills at my disposal — enabling a few weeks of abuse — but when I run out I’ll be right back where I started: desperate, alone, and in withdrawal. I know that I’m only one bad decision away from going to jail and it scares me.

America’s prisons and jails now hold an estimated 2.3 million men and women, many of whom are first-time, non-violent drug addicts who’ve committed property crimes such as theft, dealing in stolen property, burglary, prostitution, and fraud. Inside the criminal justice system, treatment and rehabilitation are seldom considered an option, and many of these crimes will carry a mandatory-minimum sentence, overcrowding institutions to the point of crisis.

Two days is a very long time to lie in bed buzzed on morphine, ruminating over your existence. I’m finally able to walk to the bathroom unassisted and take a hot shower — maybe the best shower of my whole life — and I’m nourished, rested, and clean. I have enough opiates in my veins to knock down a horse, but even after the extreme and pathetic lengths I went to in arriving at this moment, I’m already thinking about partying when I leave. This idea fills me with disgust. As I shave and look into my glassy blue eyes in the mirror, I can’t help but feel empty inside. Why can’t I just can’t shake this monkey off my back long enough to heal? My chi is no longer my own; it’s been hijacked by the ebb and flow of addiction — my current raison d’être. And now it’s near checkout time at the Pharma Hotel, and I’m still off the tracks.

Society has done a commendable job of spotlighting the opioid problem through news media outlets, legislation, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, President Trump’s proactive administration, the Surgeon General, the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, grieving parents, and a wide variety of sources that are intent on battling this crippling dilemma, but opium continues to destroy lives throughout the country, and the pharmaceutical companies manufacturing these harmful products have yet to be held accountable.

“Here are your prescriptions and discharge papers, Mr. Moser. Just sign here,” the young duty nurse informs me. He’s a new face and seems likeable. “You have an appointment scheduled in two weeks to have the staples removed. Good luck and take care of yourself.”

I unplug my cell from the charger, hesitant to leave the comfort and security of my nice accommodations. Over the last three nights, I haven’t had to hustle for a motel room, go hungry, or worry about my next score; my guard was down and I was relaxed. Now, my anxiety about running the streets returns to my psyche like an ex-stalker. I may be holding two bottles filled with Oxycontin and Dilaudid, but they can’t erase the problems I’ve created for myself outside these walls. The stocky nurse stands in front of me, waiting patiently as I accept the reality of leaving

“Thanks, man,” I muster weakly.

“Jake. You’re welcome.” I introduce myself and we shake hands. “Can I make a suggestion to you?”

“Sure.”

“Get some help. You don’t want to live like this. You seem like you have so much potential and it’s a shame to see it wasted.” He hands me a folder with some paperwork. “Here’s a list of treatment centers and meeting places and times for Narcotics Anonymous. I know it’s not really my business, but I want to help.”

Since the moment I walked through the hospital doors, every interaction I’ve had has been filled with an underlying embarrassment about my weakness; my insecurities have been on overdrive and only masked by a constant stream of heavy narcotics to numb my pain. But standing here in front of this caring, kindhearted nurse, I feel… a glimmer of hope. I’m moved that a stranger sees past my transgressions and wants to help me climb out of the insidious abyss. Jake’s affability reminds me of normal life, of being around sober people who work and have barbecues and take kids to soccer practice and make plans about the future. Of the everyday commoners who share love and good times with someone special. Ordinary people who’ve overcome ordinary unhappiness without drugs or alcohol; who strive for something real and true in life with purpose and determination; who have a circle of friends, family, and co-workers to lean into on this planet of uncertainty and occasional loss. Jake’s empathy inspires me to do something better. I’m mentally revitalized and want to try anything different. I want to stop the cycle of damage and destruction that I always leave in my wake and try to get back to the way things used to be. I sincerely want to change, but I just don’t know how. It’s like I fell off a cliff and the rope to save me is just beyond my grasp the whole way down.

Fentanyl, Oxycontin, Percocet, codeine syrup, methadone, morphine, and heroin are all commonly abused opiates that are now part of our everyday conversation. Law enforcement agents have shut down “pill mills” in many states, while lawmakers pressure overzealous doctors with bills aimed at stemming excessive pain pill prescriptions. The National Institute of Health — whose director is onboard with affordable treatments and non-addictive therapies for people with chronic pain — is encouraging the medical community to come up with progressive solutions to the problem.

I look at Jake with a renewed sense of optimism, and ask him if he’ll walk with me downstairs. We talk like old friends, and it feels so good to have a normal conversation. Both of us have sons the same age, and we share stories about their adventures and sports. When we step out of the elevator, I slow my pace and lower my voice.

“Look, Jake, I’m messed up right now, but I’m not a bad guy. I promise. If we met under different circumstances—”

“We’d coach Little League together?” he says.

My heart softens at the image of seeing my boy play ball again, and I choke up. “Yeah… yeah… so you understand.”

The lobby is cavernous and echoing with footsteps as I steer toward the front doors with trepidation. I’m scared to leave, to head back into the crazy world of tricks and manipulations, violence and new regrets. Jake sees the fear in my eyes and grabs my cell out of my hand.

“This is my number, bro. Go to a meeting, get clean, and call me up sometime soon. I need a third baseman for our softball team, and you look like a power hitter,” he says with a smile.

We shake hands goodbye and I step through the door, blinded by the splintering sunlight and hoping for a new beginning. And while I know that it may just be out of reach, I’m so willing to try.

Drug addiction is now classified as a disease by the American Psychiatric Association and the New England Journal of Medicine.

Further Reading

- From the Prison Writing archives: “Under the Bridge” by Christiana Justice

- Read more about the criminalization of addiction