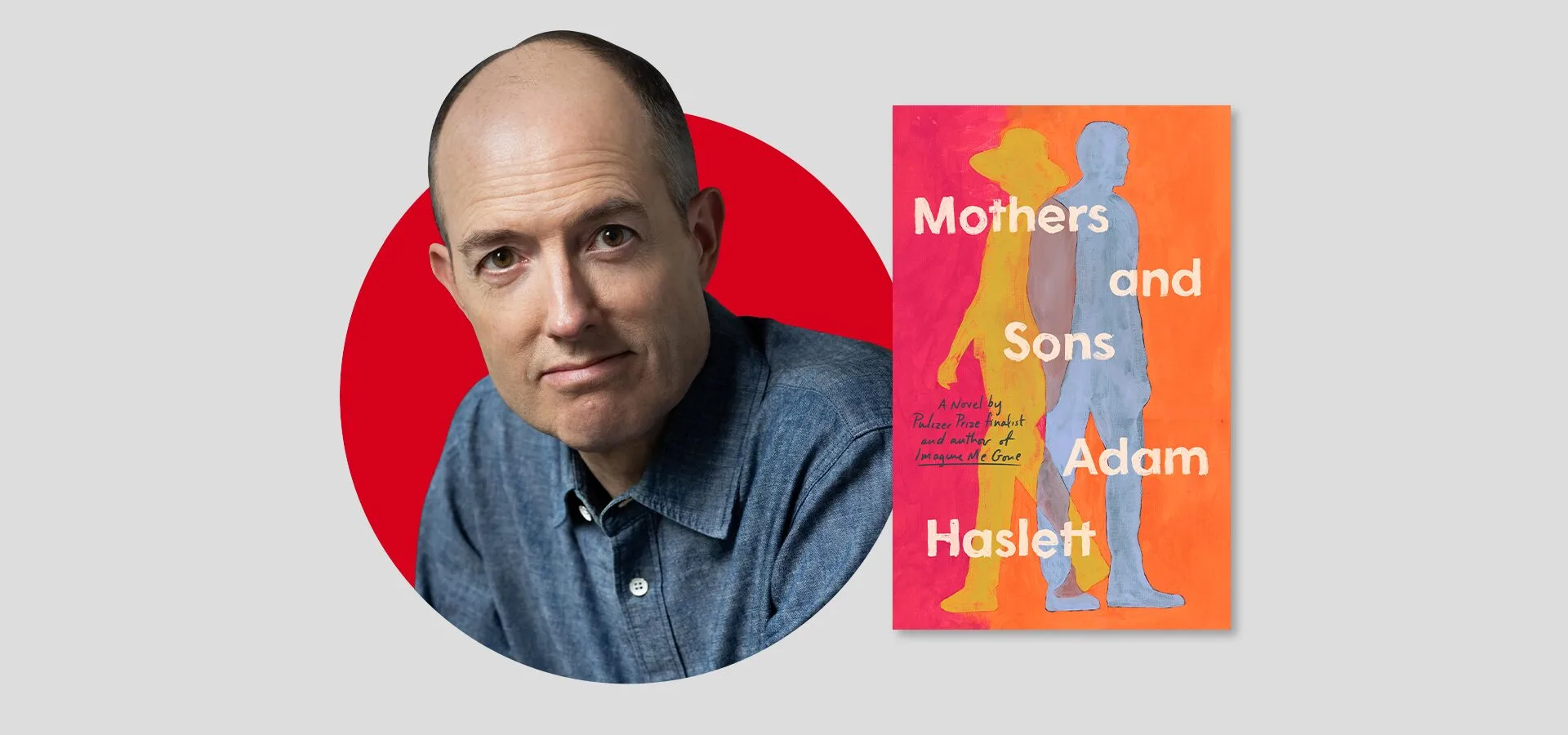

Adam Haslett | The PEN Ten

Mothers and Sons (Little, Brown, 2025), the newest novel by Pulitzer Prize nominee Adam Haslett, concerns itself with the chilly yet tenacious relationship between a 40-year-old reclusive immigration lawyer and his mother, a former Episcopal priest who runs a women’s retreat in Vermont. With distinct precision, Haslett incrementally unspools a family history of heartbreak and regret, exploring how a single event can rupture a bond, while vulnerability and honesty might offer a route to repair.

In conversation with Campus Free Speech Program Manager Aileen Lambert, Haslett discusses seeing himself as a “method” writer, medieval abbess Hildegard von Bingen, and the challenge of helping (and writing about) others without cutting oneself off. (Bookshop; Barnes & Noble)

Your protagonist, Peter, is a civil rights lawyer defending immigrants seeking asylum in the United States. You also have a JD. What is the greatest similarity and the greatest difference between being a lawyer and being a novelist?

Well to be fair, I’ve never practiced as an attorney, though many of my friends do. That said, the similarity between a lawyer and a writer is that they both rely on words—sentences and paragraphs that make up the briefs or chapters they produce—to convince others of something. A legal argument in the case of a lawyer, an imagined world in the case of a novelist. There’s print and paper and little else. No music, no special effects. So the precision of language (if not originality for lawyers) is paramount for both. I also think there’s a sense in which, at least to be an asylum lawyer, you have to have the mental capacity to put yourself in other people’s shoes in order to figure out the best way to help them. And at least for me, that’s what fiction is all about—imagining, in detail, the lives of others. As for the differences there are too many to number, but to cite just one: novelists don’t have clients. Their readers might be disappointed by shoddy work, but no one gets hurt.

This book is set in 2011, yet the current politics about immigration never felt far from my mind while reading. When did you start working on this novel? What stood out to you during the writing process as time went on?

I started work in earnest on the book in 2019. As soon as I realized the main character would be an immigration lawyer I knew I had a choice to make: set it before Trump or after. Given that the immigration system and the political discourse around it has been broken for decades—Obama and Biden both deported more people than Trump in his first administration—it wasn’t as if I needed to set it post 2016 to depict an overworked lawyer and his relationship to his clients, and that was what really interested me. And as I went on with the writing that is what pulled me in more and more, what late in the book Peter describes as “intimacy without intimacy,” that proximity that a lawyer has to the hardest experiences an asylum seeker has likely ever been through, yet without the time or form of connection of, say, a therapist or minister, who tries to look to the whole person. It’s a very particular relationship conducted under stress and with huge consequences. To state the obvious, the flagrant cruelty and meanness of the current administration already has and will continue to add to this stress. Which is itself purposeful. And which is why supporting people in these jobs is so important.

At the beginning of the novel, Peter’s boss Phoebe, also an immigration lawyer, says, “Some clients get under your skin. I’m saying it so it doesn’t just pile up inside. That’s how we shut down, that’s how we become bad lawyers.” How do you practice not shutting down as a novelist?

That’s a great question. I think of myself as a “method” writer, in the acting sense of the word, which is to say I spend much of my writing time trying to occupy the self-states that my characters are experiencing. So if Peter is rather numb and cut off from himself, at least for the hours at the desk, I’m trying to get inside that experience. Which is what made writing Peter’s early scenes in the book the hardest part of writing this novel, because I was spending time in a mind shorn of much feeling at all. It’s a privilege to have the time to absorb myself in this way, but the difficulty of it is it’s not always easy to leave at the desk. Again, because this is all in my imagination, and because I can take a day or a week off of writing if I need to, the consequences of these ghosts piling up in me isn’t as stark as it is for Peter in his world. As for how I practice not shutting down, I would say daily sitting meditation is the most practical means.

As I went on with the writing that is what pulled me in more and more, what late in the book Peter describes as “intimacy without intimacy,” that proximity that a lawyer has to the hardest experiences an asylum seeker has likely ever been through, yet without the time or form of connection of, say, a therapist or minister, who tries to look to the whole person. It’s a very particular relationship conducted under stress and with huge consequences.

The novel lets the reader into the haunting details of Peter’s past incrementally as he processes his adolescent grief, guilt, and regret. This builds to an intense and effective reveal at the climax of the story. How do you practice pacing in your writing?

In Mothers and Sons I had the sense of wanting to give the book some of the lyric concision of a short story (I thought at first it would be quite a short novel but it ended up being about the length of my other two). And one of the things this meant was having the kind of beat-by-beat awareness of where the reader’s knowledge of events stood, in the way you need to have in writing a short story, a form so eminently about pacing. This is one of the reasons it took me a long time to write this book. I wanted to attend to that pacing page by page. Which was mostly about careful revision, and then getting a deep edit from my editor Ben George, who is very good at clocking these sorts of things. At some point you’ve rewritten certain scenes so many times you lose perspective on how they’re functioning within the whole. And that’s where a good editor is indispensable.

Ann’s retreat center is named Viriditas, after the Latin word associated with the medieval abbess Hildegard von Bingen, who used it to refer to spiritual or physical health. How did you come across this concept and decide to use it in the novel?

My partner is a composer and a few years ago he had a commission to set some of Hildegard von Bingen’s invented language, her Lingua Ignota, a lexicon that seems to have been her way to get at spiritual concepts she felt couldn’t be expressed in existing languages. That’s how I came to hear the term Viriditas, which was an important concept to her. She saw it as a force that ran through all living things, associated with verdancy, growth, and the power of plants and animals to renew themselves. All of which seemed apt to the mission of the retreat center that Ann helps to found in the book, though it’s Clare, the former religion professor, who suggests the name. It’s also true that I just liked the sound of the word.

Peter uses work to distract him from painful memories, while Ann uses religion, meditation, and nonattachment to justify emotional distance. What interested you in the different ways people might avoid processing their difficult feelings?

The parallel you refer to is obvious to me now that the book is done, but to be honest I wasn’t as aware of it while writing. My goal is always to get as far inside a character’s way of being in the world as I can, and each person’s manner of coping with their experience is different. Which is just to say that I came up with these attributes of Peter (his almost exclusive focus on work) and Ann (her meditative groundedness) in trying to make sense of them as individuals, not thinking of them as twinned. And then, of course, it turns out their ways of coping with the things they don’t want to see share a family resemblance: they help others. Which I think, to be honest, is part of the psychic life of liberalism, as Ann herself thinks at one point. To help others can also be, ironically, to distance yourself from them, and from yourself. Not always, by any means, but there is always that danger of condescension.

What is the most impactful depiction of a mother/son relationship you have encountered in literature?

The tricky thing about a question like this is that, of course, what ends up impacting us isn’t “the” depiction itself, but the memories of it we retain, which like all memories may well be distorted. That being said, the depictions that come to mind are the narrator and his mother in Proust. She isn’t the central woman in the book, but the scenes of her and Marcel are just so incredibly rich and lovingly done. The mother and son in St. Augustine’s Confessions, talking in that window as they look down over the gardens of Ostia. That scene was in my mind writing this book. Monica has spent much of her adult life trying to bring her son back to God, and they have this glimpse of joy together. And a third, in stark contrast, but again from the son’s point of view, would be Meursault in The Stranger, for the mystery of his lack of any grief at all at his mother’s death, a lack that is the driving force of that book.

To help others can also be, ironically, to distance yourself from them, and from yourself. Not always, by any means, but there is always that danger of condescension.

What is the last thing you read that made you see the world in a different way? (Anything from a book to a billboard to a cereal box).

Ned Blackhawk’s book, The Rediscovery of America, Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History. It’s a remarkable history of indigenous communities in North America over nearly five hundred years. One of the most revelatory episodes for me is how settlers in Western Pennsylvania in the pre and post Revolutionary period managed over two or three decades to shift the nascent political establishment’s view away from the treaty making and trade with native tribes that had gone on for a century and a half toward a more openly genocidal and eliminationist approach to all Indians, regardless of which side a tribe had fought on in the war with Britain. It’s such a stark example of how a racialized, settler ideology moves from the fringe of a body politic to the very center of it. Which, two hundred and fifty years later, we see playing out again with the politics of the U.S. border, in what is, ironically enough, described as American “nativism.”

What are three words you would use to describe your own mother?

Wise, generous, loving.

Everyone comes from different places, literally and figuratively, and the dilemmas or challenges they’re grappling with are different. So if I were to give the same advice all the time, it wouldn’t be all that helpful.

In addition to being a novelist, you also teach creative writing. What is the hardest part about teaching writing? What is the best?

The hardest part is trying to discern what a graduate student is most in need of to clarify and strengthen their work. Everyone comes from different places, literally and figuratively, and the dilemmas or challenges they’re grappling with are different. So if I were to give the same advice all the time, it wouldn’t be all that helpful. But this leads fairly naturally to the best part: getting to know younger writers, reading their work, and most of all getting to discuss it with them so I can understand not just the words on the page, but the ideas and interests that lie behind them. Which is when teaching really becomes a conversation, and getting to have conversations about stories and fiction and how to translate life into art—that can be both meaningful and pleasurable.

Adam Haslett is the author of the story collection You Are Not a Stranger Here and the novels Union Atlantic and Imagine Me Gone. He has twice been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, as well as a finalist for the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award and a winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. He is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, the PEN/Malamud Award, the Berlin Prize, and the Strauss Living Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He currently directs the MFA Program at Hunter College in New York.