This Q&A is part of a series of interviews with journalists and experts who regularly handle disinformation. The interviews will appear regularly through the election and beyond to highlight best practices, insights, case studies and tips. Our goal is to provide a resource to assist reporters and community members through the news events of 2024.

Lauren Weber has been covering health policy for a long time. At The Washington Post, she focuses on accountability stories – specifically, the forces promoting scientific and medical disinformation. Her coverage includes the impacts of birth control misinformation, the lucrative world of covid misinformation and the toll of malnutrition on children in Gaza. She said she prioritizes these types of stories because they go a long way in highlighting the truth.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Something I’ve heard a lot about when it comes to covering false information is getting ahead of it before it spreads, because it’s so hard to change people’s minds. How do you track those narratives or pieces of false information and get ahead of them?

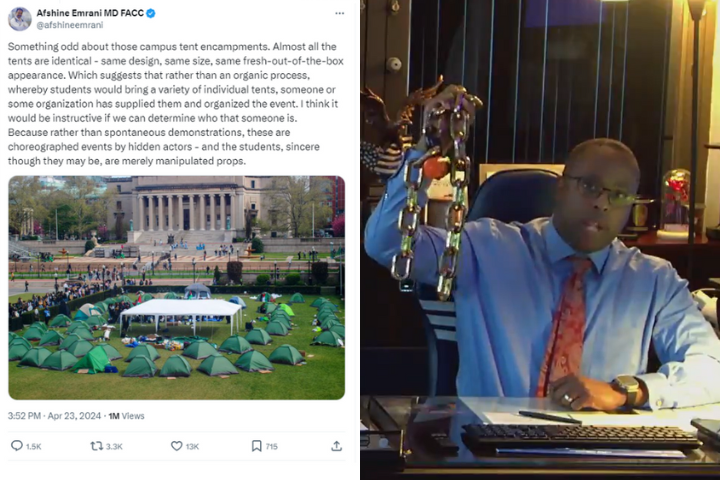

The way that I track misinfo and disinfo narratives on my beat – and again, my beat is a health-care accountability reporter focused on medical and scientific misinformation – is I read, I read, and I read some more. I follow a lot of spaces that mainstream media is not looking at, whether those are substacks of folks spreading medical misinformation, Rumble channels, Twitter, various social media platforms. I track all of that to see what’s bubbling up and what folks are talking about that maybe people don’t realize. My job is to illuminate for readers the trends in the health misinfo space that they may not see the connective tissue on, but that they see on their social media. My favorite stories often involve following the money once we’ve established that kind of narrative, because it’s really interesting to dig into what’s behind some of these misinformation campaigns and who could potentially be profiting off of them.

What would you say is your biggest concern as a journalist navigating misinformation?

I think it’s really hard in today’s day and age, when there’s an absolute lack of trust – not just for the media, but for physicians, which on my beat is particularly interesting – for the average person to know what’s up from down. The average person does not have a medical degree, so if they come across medical misinfo, they may not be able to tell what’s right from wrong. And that’s what I try to do in this coverage, is walk through how people are being misled and why. And it’s a full-time job. People don’t have the time to do that while they’re scrolling on TikTok at night. They’re not thinking, “Oh, am I being misled by this Instagram post, this TikTok post?” That’s not usually their mindset. And I think it is really hard to distinguish who is doing something for profit versus who’s telling the truth in today’s media environment that’s so fragmented by social media.

How do you maintain trust with readers as you’re covering something that might encourage them to remain so skeptical and distrustful?

It’s really important to be fair and meet people where they are and hear their perspective, always listening to different folks as they approach different issues. And also being clear. If you don’t walk clearly through a complex medical concept to talk through what is misinformation, it’s really hard for people to understand what you’re even talking about. Accuracy and clarity are really important in this instance.

Is there anything that you’ve noticed works particularly well that reporters do – or maybe not as well – in the misinformation space?

Something that we could all get better at – and it’s something I try to do but continue to work to improve upon – is clearly explaining concepts, walking through, “Hey, this is a piece of misinformation. This is a sentence that is incorrect. Here’s why it’s incorrect.” And giving the background on that. That’s hard to do clearly, concisely and in a way that makes a story still readable. But it’s so important to have that kind of context because our job is to show, not to tell. Our job is to present the facts to readers, and I think that clarity through facts in the misinformation space is vital.

A lot of what we’re trying to do is talk to journalists about the election, but misinformation spreads in so many spaces: climate, health, pop culture. What do you think political and other journalists can learn from how misinformation spreads in the medical world and how that is covered?

One of my sources once told me that there’s always been, since the beginning of time, people selling snake oil cures for things – it just used to be in the town square. But in the era of social media, now everyone can access different snake oil cures. Now everyone can potentially be misled by folks who are selling or promoting some sort of medical misinformation that could have real patient harm. The same goes for national political reporters – everyone is given a megaphone in today’s interconnected day and age. Especially in the constant breaking news environment that we’re in, it’s really important to take a step back and make sure that anything you’re consuming, you know where it’s coming from, and that it’s not a part of a narrative that you unwittingly are falling into that may or may not be truthful. It’s important to consider, as always, the sources of where you get information and make sure that you’re consuming them in a responsible way.

Some journalists are hesitant to get into covering misinformation or calling it out because it could open you up to harassment and online abuse. Do you have any advice for how to handle that?

I’ve had personal attacks, not only on my work, but on my appearance. The attacks on my work, that’s fine. You can critique the work. It’s fair to have a critique of reporting. There’s obviously feedback to be given. I’m not a perfect person, I can always improve. But it’s hard to have personal attacks on your appearance, especially as a woman in media today. I am really grateful that I work at The Washington Post, because not only do I have editors that back me up and take care of me when I’m in the middle of some sort of media frenzy over a recent article of mine, but I also have the legal team that comes with The Washington Post. Most of my stories are lawyered, and that brings a lot of peace of mind. I know that I am lucky to work at a large outlet that has these kinds of resources and I recognize that it can be particularly difficult for those that are at smaller outlets. But I do think it’s really important to know that if you’re covering the truth, you’re covering the truth, and you’re doing your job.

When someone running for office is espousing conspiracy theories or false information about vaccines, and media organizations are fact-checking and saying it’s false over and over again, it can be demoralizing. People start to feel like, “Are we doing the right thing? Should we stop covering this?” How do you navigate that?

That’s a hard question, because obviously, it’s dependent on the subject at hand. I think whenever you are covering anything like anti-vaccine rhetoric, it’s really important to describe it as false if there are statements made that are false – and, again, that is up for the reader to read and learn from. I’m not sure that I have a good answer, but I think putting your head in the sand and saying you’re not going to cover it doesn’t solve the problem, either, especially in matters of national coverage. I do understand how people can get frustrated if they feel like what they’re reporting isn’t breaking through. But my job is just to report the news, and people will do with that what they will.

Do you have any advice for covering politicians who might continuously spread falsehoods?

It’s important to do the step-back enterprise accountability pieces – and I’m lucky enough to get to do this for The Post – where you dig through tax records and, potentially, how groups are profiting off of misinformation. You present for readers the cold, hard facts and numbers and statistics that rebut some of these statements that politicians or nonprofits or others are making that have potential for harm. Doing your job to bring to light, in the most comprehensive way possible, the motivations for that and the potential profit motives for that goes a long way.

Is there anything else that you want to touch on that you think I didn’t ask about, or that you think is important to get across when talking about misinformation?

I wrote a story in January that examined through tax records the lucrative world of covid misinformation. I found that four major nonprofits that rose to prominence during the coronavirus pandemic by capitalizing on the spread of medical misinformation collectively gained more than $118 million between 2020 and 2022, enabling those groups to deepen their influence in statehouses, courtrooms and communities across the country. Stories like that, that take a step back and take a look at these groups are the kinds of stories I get to do on this beat that shed light on misinformation in a different way than just fact-checking it.

Lauren Weber joined The Washington Post last year as a health accountability reporter. She previously covered the public health system for Kaiser Health News and was a health policy enterprise reporter at The Huffington Post.