George Packer | The PEN Ten Interview

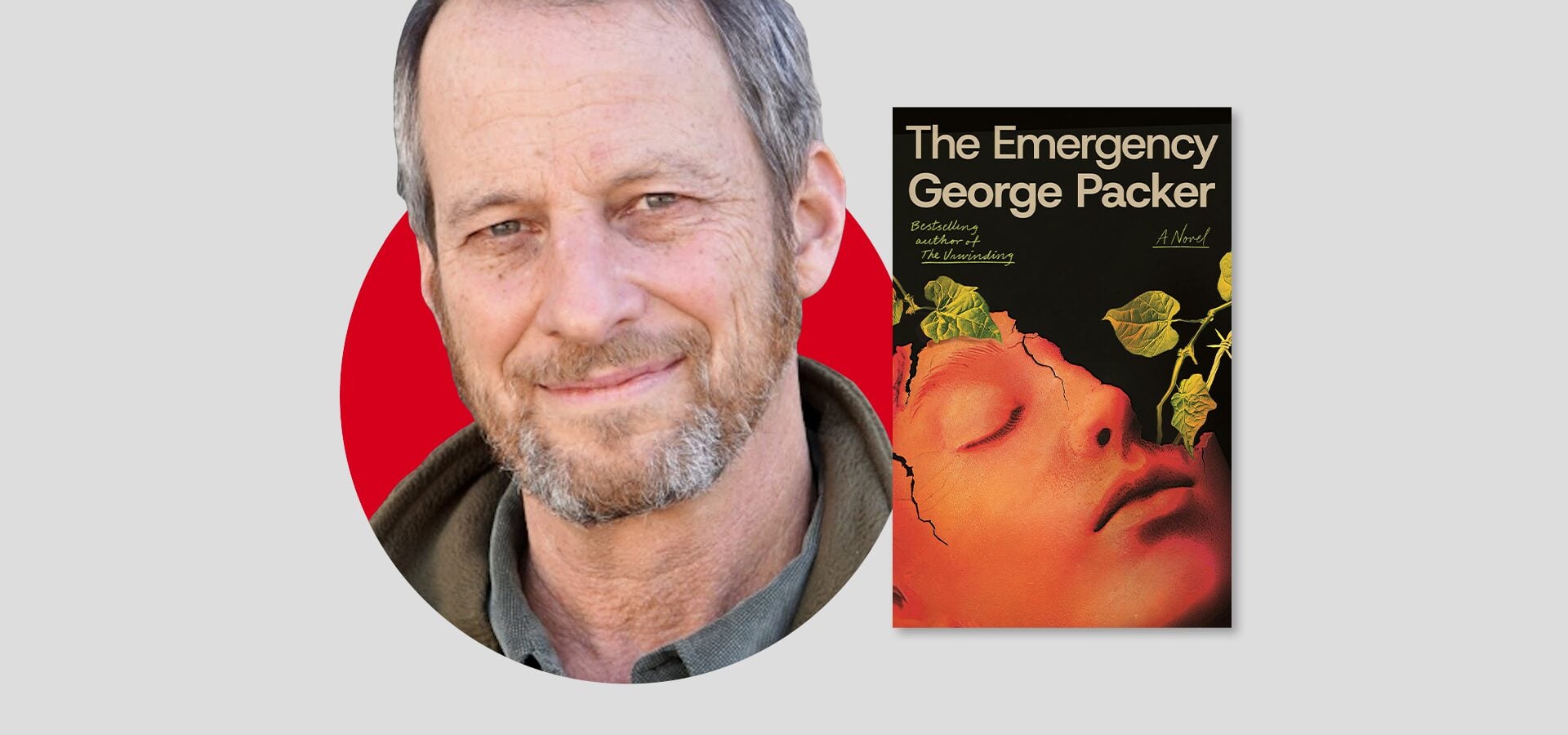

After more than 20 years away from fiction, George Packer has returned with an urgent read — though the renowned author and journalist hasn’t left reality entirely behind in his new novel. The Emergency follows Hugo Rustin, an accomplished though idealistic doctor, as he encounters rebellions led by young people in the wake of their empire’s collapse. Defined by escalating political turbulence and polarization, Packer’s dystopian world brings us face-to-face with many of the most troubling features of our own society (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2025).

In conversation with PEN America’s Communications Assistant, Julia Goldberg, Packer discusses the passage from 1984 he kept revisiting for inspiration while writing the novel, the dangers of myth-making, and how our own society might begin to recover from moral ruin (Greenlight Bookstore).

Brooklyn Public Library and PEN America are hosting George Packer to discuss The Emergency in conversation with Jennifer Senior on Thursday, Nov. 13. Register now.

The Emergency is your first novel in more than 20 years. What drew you back to fiction? What possibilities does allegory specifically hold that nonfiction might not?

A few years ago, I began to lose faith in the power of facts to create any kind of shared reality. I wanted to get away from the tired language and arguments, all the dead ends, of America in the Trump years. But I couldn’t leave our world completely behind. My writing is always going to be political somehow or other. What I wanted was to get below the surface to the deeper feeling of what it’s like to be alive today, to see the country I’d known all my life seem to disappear. The best way to get to the heart of this experience is with fiction, not journalism—not realistic fiction, but a novel that removes every familiar distraction of our time and place. So I began to think of an allegory.

The novel ends with a poignant scene in which, as the conflict between the urban Burghers and rural Yeomen continues to escalate outside of the Rustin family’s home, the home itself becomes a safe haven for wounded members of both parties. In our own divided political climate, what do you think it might take for Americans to demonstrate the same willingness to open their doors to anyone, metaphorically speaking?

Like the doctor and his daughter, we Americans have to take the risk to go out and encounter, really see, the other, and then allow our cherished ideas and illusions and vanities to be brought low, without losing core values. We need to face our country’s moral collapse and return to human decency, common humanity—something more basic and universal than politics.

The Emergency rotates through three perspectives: that of Dr. Hugo Rustin, his daughter, and his wife. Why did you opt to narrate the novel through all three characters’ perspectives rather than Rustin’s alone? Did you ever consider featuring the perspective of a character outside of the family unit (or even a Yeoman or Stranger)?

I started with the idea of writing the whole novel through Rustin’s point of view. But when the story moved from the city to the countryside, the energy suddenly flagged. Ayad Akhtar suggested: Why not shift to the daughter, Selva, and see what happens? This was intimidating because I’ve never been a 14-year-old girl, but my wife reminded me that they’re not a separate species. (I’m also the father of two teenagers.) Almost immediately the writing got me interested again—there was a renewed vitality. Seeing the world through Selva’s eyes was actually a joy. And this excitement continued in the third section, when the story returns to the city and the perspective of Annabelle, the doctor’s wife. This way the protagonists can be seen from inside and out, the imagined world becomes richer and more complex, the plot intensifies.

As for other perspectives, including Yeomen and Strangers: I hope they’re also three-dimensional characters, but I don’t have the ability to write the kind of novel where a whole gallery of people and even the dog get their turn with a point of view. Three characters was already pushing it.

We need to face our country’s moral collapse and return to human decency, common humanity—something more basic and universal than politics.

The principles and rituals of the Burghers’ new political system, Together — especially its unwillingness to tolerate dissent — have earned your novel the descriptor “Orwellian.” As the editor of a two-volume edition of George Orwell’s essays, you’re quite familiar with his work. Did you revisit any of his essays or literature while writing The Emergency? If so, were there any specific scenes or passages you found particularly rich or generative?

I’m always revisiting Orwell. For this novel, essays like “Politics and the English Language” and “Why I Write” were important, but most of all 1984. I even splurged on a facsimile of an early draft to see the handwritten changes. Our problem is not the same as 20th-century totalitarianism—at bottom we have a crisis of social conflict and epistemic nihilism, which Trump has fed and exploited. There’s no Big Brother or apparatus of surveillance and torture in The Emergency because I wanted to emphasize the role ordinary people play in ideological oppression. What 1984 inspired was the idea of building a whole alternate world. There’s a passage, not at all famous, where Winston Smith eats lunch in a gritty underground cafeteria with his colleagues in the Ministry of Truth. In just a few pages Orwell takes this ordinary scene and fills it with vivid details of existence in Oceania. I read (and listened to) it again and again to see how he combines narrative and invention so naturally that you think: Yes, this is the world.

Rustin observes early in the novel that Together relies on shame rather than fear, on social coercion rather than legal punishment. At one point he states, “A list of banned words and forbidden ideas posted next to a Together sign would seem clumsy, harsh, and people might openly flout it. Much better if the ban lived only in the eyes of others.” How do shame and fear function in our own society, where we have hundreds of banned words and thousands of banned books?

It’s probably easier to believe that about social coercion if you don’t live under official terror. But we’re learning in this country how much pressure the state can bring to bear on words and ideas. Shame, which comes from how you’re seen by your own group, is the main coercive tool of the progressive left—not official bans, but online mobs that enforce rigid moral codes. Intimidation by state power is the tool of the MAGA right, and it’s inflicted on the enemy. Social censorship is dangerous, but official censorship is worse.

Myth-making pervades your novel: The old Empire, as well as the two dueling groups it once comprised, each invent and spread stories about themselves and their values. What impulses did you want to explore through these tales?

I wanted to convey how it’s possible to imagine that a particular way of life is permanent and fail to see that it’s already ending; to believe we’re all fellow citizens only to become enemies almost overnight; to start with a shared sense of what’s real and then lose it, often deliberately, to fantasies and lies. For example, Burgher schoolchildren are taught a “Together” song about an imaginary girl called Brave Bella and a plot against the city by outsiders; only, market women discuss the song as if the girl and the plot are real. A moment of crisis for Rustin comes when a Yeoman pig farmer he’s always considered a friend expresses ludicrous and derogatory theories about city Burghers. Ordinary human connection becomes impossible.

There’s no Big Brother or apparatus of surveillance and torture in The Emergency because I wanted to emphasize the role ordinary people play in ideological oppression.

Better Humans, or “perfected” machine replicas of Burgher citizens, hold the promise of a society devoid of conflict and error — which is, of course, also a society devoid of difference and change. In such a world, “the place of the human individual will be uncertain.” To what extent did the rise of AI inform your thinking about Better Humans? In what ways do you think AI, like Better Humans, poses a threat to our individuality and thus to our humanity?

Better Humans are a kind of pre-digital AI. There’s almost no technology in the novel—again, I wanted to strip away particulars like computers and phones—but there are plenty of echoes of the way digital culture dehumanizes us. AI frightens me as much as political authoritarianism because they both rob us of individual agency, the fullest expression of our humanity. The threat is not just losing what makes us human but abandoning it. An impulse to escape this burden appears throughout the novel, in the city and countryside, among Burghers and Yeomen—especially the young. The creator of Better Humans tells Rustin that the city’s youth keep coming to his workshop to escape “the pain of being human.”

How did writing this novel change the way you think and feel about our political landscape, as a journalist and as an American?

I’ve never expected that we will have another civil war in this country, but when I finished the novel—which ends in conflict between Burghers and Yeomen—I felt that widespread violence might be only a shot away. Using my imagination as a novelist allowed me, forced me, to keep it alive as a journalist. And it reminded me of what’s at stake: the human bonds within families and societies that give life meaning.

Toward the end of the novel, the Yeomen begin desecrating the Burgher’s city with a frankly horrifying invention: a “shitapult.” Shortly before the book’s release, on October 20, the president reposted an AI-generated video of himself dumping feces on No Kings protestors. What was your initial reaction to hearing the news? Did you actually anticipate that our society might stoop as low as the characters in your novel?

I was shocked by the video—which doesn’t happen much anymore—and disturbed that my far-fetched invention had intuited the president’s mind. I guess that’s how fiction can outrun journalism. The “shitapult” is a weapon that brings everyone it touches to the lowest level—an expression of pure nihilism. It’s a disgusting image for a state of moral being, intended as satire, not prediction. But it doesn’t have the last word in the novel.

Using my imagination as a novelist allowed me, forced me, to keep it alive as a journalist.

What’s next for you? Would you consider writing more fiction down the line?

If another novel comes to me I won’t close the door on it, because writing The Emergency was a happy, sometimes even exhilarating, experience. But it also refreshed my appetite for reality, and my next book will return to that.

George Packer is a US journalist, award winning author, playwright and a staff writer at The Atlantic. He is the author of 10 books, including The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America (a winner of the 2013 National Book Award); Our Man: Richard Holbrooke and the End of the American Century (the winner of the 2019 Hitchens Prize and Los Angeles Times Book Prize); and, most recently, Last Best Hope: America in Crisis and Renewal. Before joining The Atlantic in 2018, he was a staff writer at The New Yorker for 15 years. He writes about American politics, culture and U.S. foreign policy.

Packer has been a Guggenheim fellow and twice a fellow at the American Academy in Berlin; he is also a 2016-17 Cullman fellow at the New York Public Library. He was also an Eric & Wendy Schmidt Fellow in 2017 and an Arizona State University Future of War Fellow in 2018. George is a Yale College graduate and served in the Peace-Corps in Togo.