It is 1957. San Francisco. Two undercover cops enter City Lights Bookstore and arrest the cashier. Also in cuffs is owner and publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti. His crime: publishing Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems. His charge: Selling obscene material.

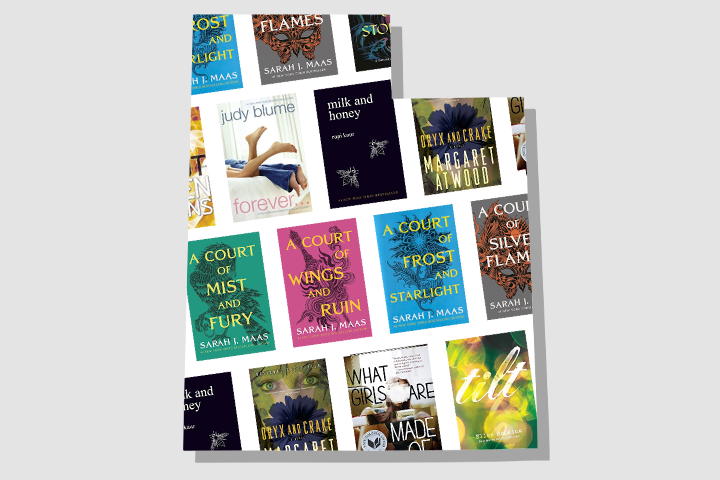

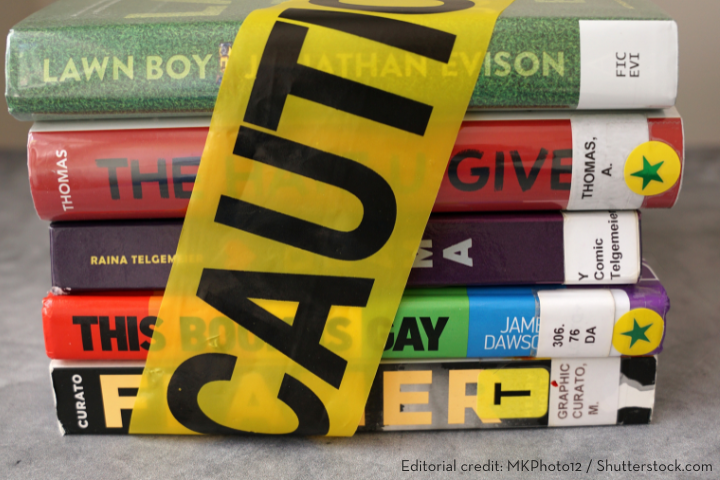

It is 2024. All across the United States. More than 10,000 instances of book bans are recorded by PEN America in the past academic year. The reason: alleged sexually explicit material and “critical race theory.” The targets: books featuring people or characters of color and/or LGBTQ+ people.

Book bans are not new, but they are increasingly becoming noteworthy because of both the frequency and intensity at which they are happening, spreading across the country.

“It really boils down to this being about democracy,” said Ipek S. Burnett, co-chair of Human Rights Watch executive committee, San Francisco, and a writer. “Whose voices get heard and whose voices get silenced, whose stories, perspectives, voices are welcomed and included, and whose are marginalized and rejected, repressed.”

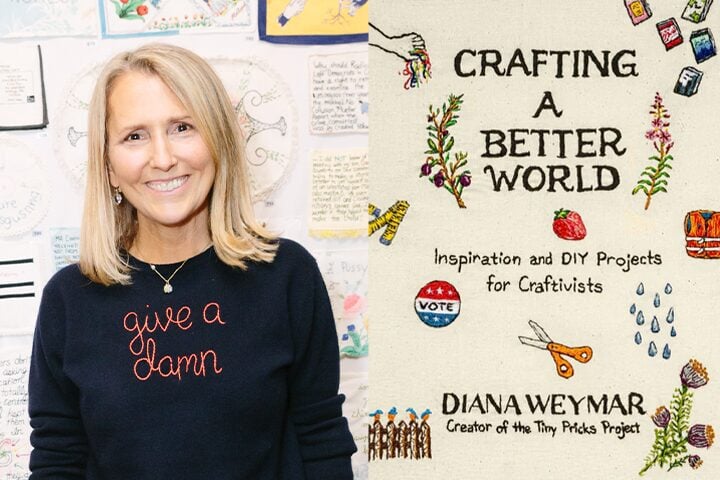

Burnett moderated the webinar panel, From Howl to Now: Book Bans in the U.S., hosted by City Lights Bookstores in San Francisco with guests Summer Lopez, PEN America’s Chief Program Officer, Free Expression; Trey Walk, democracy researcher and advocate for Human Rights Watch’s U.S. Program; Ronald K. L. Collins, co-founder and co-director (emeritus) of the History Book Festival and co-founder and co-chair of the First Amendment Salons; and David Michael Skover, former law professor at the Seattle University School of Law.

“Even as polls repeatedly show that a majority of Americans, across political lines, oppose book bans, the number of bans has increased from one school year to the next,” said Lopez, presenting the latest from PEN America’s research.

PEN America’s September 2024 Memo on School Book Bans, showed that censorship is being advanced by two key players: groups that advocate for parental rights and state legislature, and new laws in states like Iowa and Utah that allow state-wide bans that exacerbate the problem and threaten to have ripple effects across the country.

“I want to emphasize that while the term parental rights gets used a lot, it really means privileging the rights and preferences of some parents over others,” said Lopez. “It’s always reasonable for parents to have a say in what their own children read and learn, but it’s not okay for some parents to make decisions for everyone else’s children.”

More than a dozen new state laws have been implemented to ban books in schools, as districts have changed policies at the local level. This targeted banning is also often accompanied by alarming attacks on librarians and educators, including labeling them as “groomers,” Lopez added. And the effect of the campaign to ban books doesn’t stop at simply removing them from shelves, it extends to everything from librarians and teachers being more hesitant in the books they’re selecting and purchasing to cancellations of author visits and book fairs.

“I want to emphasize this movement is really largely about restricting access to a very specific set of books and stories, the books that represent the voices and stories of LGBTQ+ people and people of color – books that wrestle with the tough issues children themselves also have to,” said Lopez.

Lopez noted that the 10,000 book bans counted by PEN America is an undercount, as silent censorship the educators face goes unrecorded. “Many stories of book bans go unreported, and they also don’t capture the broader chilling effect that this movement is having on our schools,” she said.

Trey Walk from Human Rights Watch said that though book bans are a national issue, focusing on what is happening in Florida, where he predominantly works, is important as the laws get exported and the language in bills across various states is very similar. He said that book bans are a part of the broader attack on public education, which has three other prongs to it – restricting discussions about race and LGBTQ+ issues, rolling back affirmative action, and targeting diversity, equity, and inclusion in universities.

He noted the healthy activist community in Florida. “Just as Florida is a blueprint for these terrible laws, it can also be a blueprint for our activist movements and states all across the country,” said Walk, who has spent the past year traveling all over Florida, spending time with people on the ground and learning about their stories.

He presented various instances where students, educators, parents, the faith community, and cultural institutions have come together to combat book bans. He gave examples of groups like Florida Student Power that teaches students to talk to their legislators, Teach the Truth Tours which conducts educational tours to sites of Florida’s racial history, Moms for Libros, the Hispanic parents group working for books and against misinformation, and Faith in Florida that works to teach pastors how to include racial history in their sermons.

“We wanted to change this narrative that Florida is lost and help these groups recruit people to participate in their efforts,” he added. Walk also explained how people are working at various levels–from school boards to state legislature and federal government–trying to advocate for change.

“They’re in the heart of the storm,” he said of the people fighting back in Florida, “but it makes you a lot stronger to be in that heart of the storm.”

I am signaling you through the flames

The North Pole is not where it used to be.

Manifest Destiny is no longer manifest

Civilization self-destructs. Nemesis is knowing at the door

What are poets for, in such an age?

What is the use of poetry?

Burnett started the session with these lines by Lawrence Ferlinghetti, the co-founder of City Lights Bookstore and a well-known name in America’s censorship history.

“Ours is a story of a poet bookseller who was prosecuted for selling a poem,” said Skover, one of the authors of the book The People v. Ferlinghetti: The Fight to Publish Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2019). “Lawrence Ferlinghetti became a First Amendment hero.”

Along with Collins, Skover narrated the story of how Ginsberg was discovered by Ferlinghetti and began his very long tryst with America’s obscenity law. Even as late as 1942, the U.S. Supreme Court held that lewd or obscene publications received no protection from the First Amendment and were considered as having “slight social value as a step to truth” and were “outweighed by social interest in order morality.” This, in turn, allowed state and federal legislation to censor anything they deemed foul or morally unhealthy.

Reading from the poem, Skover embedded its evocative lines in the present.

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked,

dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix…

“Even to this day, ask yourself, could any school dare to have this book in their library? One of the great American poems, one of the poems that stands on the forefront of gay liberation? Would any library be able to have this book today?” asked Collins, claiming that censorship was what put Howl and Ginsberg on the map. “I think not,” he answered.

“Fundamentally, these book bans are about silencing, silencing voices that have traditionally been silenced,” said Lopez. “This language of obscenity to target queer and LGBTQ has been seen throughout history, we’ve seen this time and time again.” She added that we have seen attacks on books across the world – in Nazi Germany, apartheid South Africa, and Vladimir Putin’s Russia – and a broader attack on education in Viktor Orbán’s Hungary and Jair Bolsanaro’s Brazil.

“Pity the nation whose people are sheep. And whose shepherds mislead them,” Collins read from Ferlinghetti’s poem, inspired by poet Khalil Gibran.

Though a majority of Americans oppose book bans, the movement is spreading. And while it is impressive to see students and parents stand up despite the threats and dangers, it is important to make voices heard, especially at the local level.

“I always say if you are going to do this work, you have to be an optimist at heart, and I am,” said Lopez. “I will always believe that freedom of expression and the power of literature and stories is going to win the day.”

Walk said despite the force of people supporting book bans, the counter movement is strong. “The stakes are really high on the ground and the fact that people are still showing up, in spite of that, is a lesson we can all learn from,” he said. “The future will be freer if we make it. It is up to us; it is not guaranteed.”