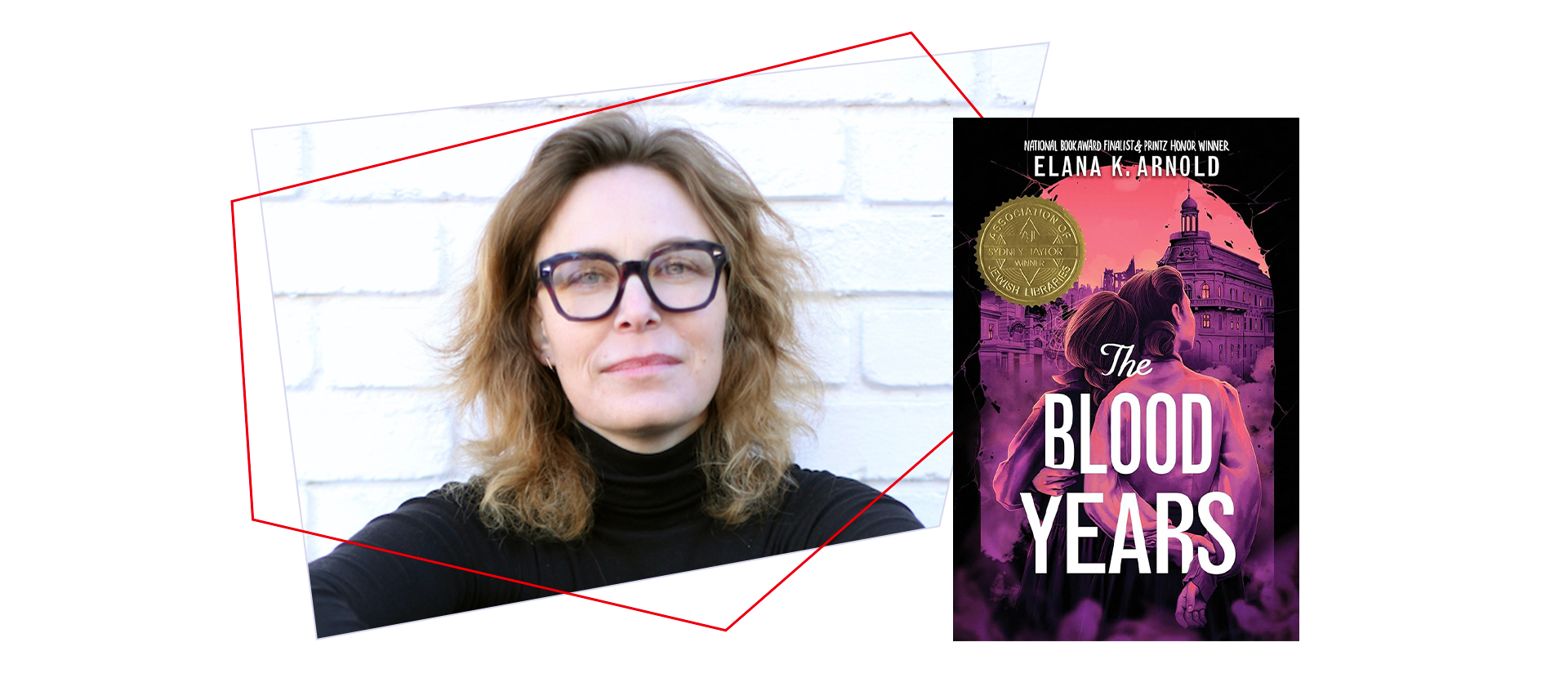

Elana K. Arnold | PEN America Member Spotlight

January 31, 2024

Author of more than 20 books for kids and teens Elana K. Arnold is no stranger to book banning. According to PEN America’s latest Index of School Book Bans, Arnold’s titles account for more than 50 instances of book bans in 29 different school districts across 11 states.

These numbers don’t discourage her from churning out award-winning titles, including The Blood Years, which was awarded the 2024 Sydney Taylor Book Award in January. This month, Arnold celebrated the publication of two more children’s books: a continuation of the adventures of Harriet the Spy, and a compelling and and hilarious tale of a fish that grants wishes.

In this interview, Arnold navigates her experience as a banned author, lends invaluable insight into craft, and shares her idea of the role of the writer in the context of kid lit.

I am so pleased to have PEN America member Elana K. Arnold with me. Thank you, Elana, for joining us.

Thank you for the invitation, Allison, and for all the work PEN America does. I’m very proud to be a member.

Congratulations on your YA novel, The Blood Years, winning the 2024 Sydney Taylor Book Award and the 2024 Young Adult Literature Award from the National Jewish Book Awards. A tale of WWII survival, I understand that the story was inspired by your own grandmother’s experience in Holocaust-era Romania. Can you talk about why you decided to write this story, specifically for a young adult audience?

I have always been an enormous fan of my grandmother’s storytelling abilities. She told me stories all my life. They got deeper and more complex the older I got, and one of my favorite subjects was true stories about her life. I heard snippets of her war years growing up, and she started with the sweet, funny stories: going to the countryside, having the geese chase her, her terrible sister, dance class, her wonderful grandfather, her mother who wouldn’t get out of bed, and all of those things.

As I got older, I started to ask more and more questions. I knew she was Jewish and I knew she survived the Holocaust. Her experience as a Jew in Czernowitz, Romania was different from, but in many ways the same as, Jews across Eastern Europe. It felt like a story I needed to tell, but it took me many years to feel that I was a writer who could even tell it. It was actually the writing of the book over seven drafts that made me the writer who could tell it.

The reason it’s a book for young adults is because my previous titles have been books for young adults. I work with a fantastic editor named Jordan Brown at HarperCollins, at Balzer and Bray. He was such a partner in caring for this book and for daring to tell me, in early drafts, that the character wasn’t on the page in a way that was so difficult for me to hear. I don’t think this book could have been what it was without his guidance.

To me, a young adult book is simply a book that centers the teenage experience as if the character is still at that young age and does not have a reflective, looking-back-from-adulthood-on-teenage-years perspective. That’s a must that separates books in the young adult category. I’d be very happy to see a challenge to that, but that’s the only parameter in the books I’ve written. I didn’t feel like there was anything I had to do differently or anything I had told back on. It was going to be published by a young adult imprint.

Why were you drawn to the children’s and YA genre? Why do you think it’s important for young readers to hear stories that challenge their understanding of their worlds? Of their cultures? Of their histories?

What authors want to give readers of any age is an opportunity to have windows into lives other than their own, whether they be out on a spaceship or back in history or in the future. That is what we do. What unites all of us authors is the desire to touch readers and allow them to see something they didn’t see before, or for us, to explore something that we didn’t completely understand when we set out to write about it.

I read once—in a psychology class, I think—that if something really traumatic and terrible happens to you, you get stuck at that age. I like to think of myself as six to eight years old, 12 to 13 years old, and 16 to 17 years old because I had different crises in my life at those three points. I think that’s why I continue to circle back to those times. I continue to untangle all the complicated things that made me who I was at those different ages.

“What authors want to give readers of any age is an opportunity to have windows into lives other than their own, whether they be out on a spaceship or back in history or in the future. That is what we do.”

In PEN America’s latest Index of School Book Bans, which tracks bans in school districts from the 2022-2023 school year, your titles account for 51 instances of book bans in 29 different school districts across 11 states. What goes through your mind when you hear these statistics?

I think about the individual number of kids who won’t ever come across my work, and that makes me very sad. I’m honestly a little surprised that the numbers aren’t even higher based on the number of Google alerts I get. Maybe they will be for ‘23/’24 because I only have Google alerts set-up for three of my books: What Girls Are Made Of, Damsel, and Red Hood. I get between one and four Google alerts almost every day. Just yesterday, I got this one that I thought was kind of perfect. It says, “St. Joseph Public Schools [Michigan] has banned Elana K. Arnold’s What Girls Are Made Of. Critics of the book claim it ‘has several instances of explicit sex, normalizes abortion, and gives accolades to Planned Parenthood.’”

I thought to myself, “Well, that’s what the people who gave me awards for this book also said.” It does do those things, and I’m very proud of those things. It’s just such a clear divide. Sometimes, I see things that are terrible. They call my books pornography, or they call me a pedophile or a groomer. That hurts my guts. But I see this and it makes me laugh.

“I think about the individual number of kids who won’t ever come across my work, and that makes me very sad.“

Right, cause you’re like, “that’s what girls are made of.”

Yeah, like, “Check, check, check!” Sometimes, I feel like they didn’t read the book, but this time it feels like they read it, at least. I’ve gotten better at laughing about it. For a while there, I felt this terrible, sick sense of dread all the time. But I guess you can get used to anything, which is kind of terrifying, too.

It’s not as if any writer goes into writing and says, “I’m gonna write a banned book. I want to be a banned author.” You didn’t get into this work because of that, and yet, here you are. So many of our members end up on these lists. What would your advice would be for other PEN America members who are facing book bans, or other writers who are writing what they feel creatively compelled to write about and are concerned that, because of the subject matter, because of who they are, because of where they’re going with the story or the character, that they could end up on a list?

First of all, there’s no making yourself small enough to avoid this time in history. We’re in the middle of another sort of scare. I remember the “satanic panic” in the eighties. We’re in another moral panic and I don’t think our job as writers and artists is to make ourselves smaller to try to avoid being hit. There’s just no avoiding it.

I have a few things that I tell myself. The first one is that art comes first. And art is a person alone. At least, my art is. It’s filled out by the world, of course: I am me because of all the writers I’ve read, all the terrible things that happened to me, all the great things that happened to me, all the teachers I’ve had, the privileges I’ve had. But then I turn to the page and it’s me alone. My job is to put on the blinders and focus just on the story, just on the art, being the truest I can be. That’s always vulnerable and scary, but no one else can be in the room if you’re gonna make your art.

And then craft. How do I make a story that can reach an audience? Craft takes what worked in the art and elevates it. It eliminates the things that turned out not to be necessary for the art.

And then business. How do I find a home for this, and what are people going to say about it? I don’t ask how I can trim it to make it satisfy those people, but how I can armor myself so that, when it comes, I am either so busy with the new project that I don’t have the time to care, or I’m part of an organization like PEN America so I know I’m not alone, or I’m in conversation with other writers. These are things I can do from a business perspective to allow my art to stand on its own. That’s my advice.

And for those of our members that are not Professional Members but are Reader Members, those who are here because they appreciate the power of the written word and want to advocate for the freedom to read. What’s your message to them?

First of all, thank you for joining PEN America and for turning up not only our freedom to say things and to write things, but for the reader’s freedom to have access to these things. People of all ages are entitled to every right.

When you are standing up for the freedom of writers, you’re also standing up for the freedom of readers. It takes a whole bunch of people getting together and having organizations to protect these things. When you look at the past, the question is, “How could these things happen?” And then you look around and say, “Oh, this is how those things happen. Now I can understand how it happened.” I didn’t know how fragile these things were. And now I do.

“When you are standing up for the freedom of writers, you’re also standing up for the freedom of readers.”

You’ve written so many excellent books for young readers that span a variety of topics, from picture books on gender fluidity to neurodiversity to YA fantasy novels. Are there any topics that you hope to explore through your work in the future?

I have an adult novel coming. It’s a gentle fictionalization, in some ways, of my own childhood in the eighties. I don’t know how gentle it is, but it’s a story of a little kid growing up in the eighties in a neuroatypical body and mind in a very unhealthy household, and isn’t able to see it. I’d love to see that published. It’s out on submission, so we’ll see. It’s called Little Bear and I’m very proud of it.

As far as other topics, I mean, I never really know what’s gonna please, delight, and scare me until I find it. I do find that I tend to write in clusters. Damsel and Red Hood were two fantasy novels that I wrote. Before that, I had What Girls Are Made Of and Infandus that are both about embodied shame in cisgender females.

This book I’m working on now in the YA field is another sort of historical book, but from a different perspective, and that’s really exciting to me. I’m looking at the throughlines of just post-Covid and just post-World War II time, and the cyclicality of what happens in the aftermath, because I don’t think Covid and is completely over (and fascism). How do those things align? How do people find community and put pieces together when everything they thought was true about the world is falling to pieces?

I want to read that.

I want you to. I have to finish the next draft. I just had a phone call from my wonderful editor, Jordan, yesterday, so I’m really excited to dig into revision.

Of new topics, you just published two new titles last week. They are The Fish of Small Wishes and Harriet Tells the Truth. Can you tell us a little bit about what these books are about, what was the inspiration behind them, and what your hopes are for them?

The Fish of Small Wishes is a picture book. It’s sort of a modern, original fable. It came from a bedtime story I told my daughter when she was younger. It’s about a little girl named Kiki who finds a fish in the middle of the street. When she takes it home, puts it in the bathtub, and cranks on the water, the fish tells her that it is the Fish of Small Wishes and it would like to grant her a wish. She tries to think of a wish, but each wish she comes up with is too big, so she has to make her wishes smaller and smaller. It’s very funny.

It’s a story that was based on my grandmother telling me about how her great-grandfather had brought home a carp for Passover dinner and put it in the bathtub to get it clean. There are many other fish-in-a-bathtub stories, but this is my version. I think it’s lovely and it’s beautifully illustrated by Magdalena Mora, who made such dreamy, fishy, watery illustrations—I think she’s magical. I’m really excited for kids to pick that story up.

Harriet Tells the Truth is the third in a series of gentle mysteries. It’s set on an island called Marble Island, which is kind of like Catalina Island right off the coast of our California here. They’re about a girl named Harriet who goes to spend the summer, sort of unwillingly, with her grandmother, Nanu, who runs the Bric-a-Brac B&B (it’s fun to say). Harriet encounters a mystery in each book, but the biggest mystery is, “How do we human? Why do we do the things that we do and how can we have honest, real relationships with one another and with ourselves?” I’m very proud of that.

Every book comes back to my grandmother in one way or another. My nana and I read mysteries, constantly trading the back and forth. She was a great lover of California, as am I, and she was my very best friend, like Harriet’s Nanu is for her. What I hope for them—what I hope for each and every one of my books—is that everyone in the world will read them. I want them to be in every school and every library and every home collection and I want them to win all the awards.

Good thing you don’t have a fish of small wishes.

That’s the thing. I have no control over any of that. I only have control over what I have done, and now the books will go off into the world and I wave them a loving goodbye with all my hopes for them. Then I just have to turn and put my focus back on what I’m working on next.

This afternoon you’re participating in You Are A Writer, which is a series of workshops that PEN America runs for new writers. It’s for those who are starting to think about what it means to be a writer, have started, or are relatively early in their journeys as writers. Thank you so much for lending yourself and your expertise to that community. Can you give us a little bit of what you’re going to share with them in your session?

When I was younger, I really, really wanted to finish books and become a writer and be a writer. I remember my mother telling me, “Writers write every day,” and I remember feeling this deep sense of guilt and shame about the fact that I didn’t write every day, and therefore wasn’t a real writer. It wasn’t until after I published several books, many years later, that I realized, “What the heck does she know?” She’s not a writer. Why am I pinning this sense of who I am on someone who doesn’t share that identity in any way? I realized it’s not even true for most writers. Most of us don’t write every day.

One thing that keeps people being writers and artists, regardless of whether or not they’re actually producing work at the time, is remaining deeply curious and interested in both the world outside of you and the world inside of you. All the time, always remembering to be open. When I am working on something, it feels like the universe is throwing things in front of me—if I’m willing to look for them—that fit right into my story. This means that everything can go into any story because everything is connected. Opening yourself to delight and being gentle is something that took me so long, and I’m still working on it, but nothing good comes of shame. Work doesn’t grow out of shame and fear. It grows out of gentle tending.

A big part of writing is spending enough time being a human on this earth to fill up the well, and then having this ability to hush yourself enough to let things percolate up, and remembering that sense of wonder that comes with story. No little kid feels like they don’t deserve to tell a story, or that they’re not good enough at crafting the story to tell it. When my kids were little, I truly believed that all children are born with perfect self-esteem. Our jobs as parents and caregivers is to protect what they have. And I think that’s true of a creative source, too. You have to protect your wonder and make room for it to grow. That, to me, is more important than spending time at your desk.

“Work doesn’t grow out of shame and fear. It grows out of gentle tending.”

That’s beautiful. Even for someone who doesn’t have a writing practice, it’s an important reminder.

Writing and humaning are the same thing. If you can approach your life with wonder and curiosity, it makes life better, even if you don’t ever finish a book. You have given yourself this opportunity to have a more enriching, magical life. It’s a win.

If we want kids to be people who grow up with complicated, complex stories of their own to tell, we have to make sure that the field is full of stories for them to discover that are complicated and challenging and terrifying and beautiful and all those things. I’ve done a lot of thinking about where my weird ideas come from, and a lot of them come from stories that I encountered. I think all story is one-third me (my experiences and fears and neuroses the way my brain works); one-third things outside of me (stories I have encountered in the world); and one-third “what if,” which is the playful, creative thing. I need all three of those things to come up with a story. You want that one-third “things outside of me,” for kids, to be as rich and as complicated as possible so that they can make interesting stories, themselves.

“If we want kids to be people who grow up with complicated, complex stories of their own to tell, we have to make sure that the field is full of stories for them to discover that are complicated and challenging and terrifying and beautiful and all those things.”

If my records are correct, you first joined PEN America around 2016. Why did you join PEN America, and why have you stayed a member for all these years?

The reason I joined is because writers can be lonely people. A lot of my work is spent alone in my own head, turned inward. The same reason I started to teach again is from a desire to be with other people who are thinking about things the way I am, or maybe thinking about things in ways that I’m not.

Having a support group is certainly why I joined. I just felt I wanted to and should, but now with the current situation, it feels almost like an armor to have a group that’s keeping track of these things. Otherwise, every time another one of these things comes across my email, I would have felt like I needed to follow-up and do all these things. Now, I think, “PEN America has that covered. They’re keeping track.” I can turn my work to my writing and they’re keeping an eye on the big picture and asking for me when they need me. It feels nurturing and embracing to have an organization that cares about things I care about.

Do you have a favorite banned book that you grew up with, or favorite topic that often comes under threat?

Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret was such an important book to me, growing up as a kid who didn’t really have religion, but definitely had questions, desires, and a secret interior life.

Forever by Judy Blume was another one. That answered a lot of questions for me. I’m a big Judy Bloom fan. I can still feel it in my bones the first time I read the scene where she and her boyfriend have sex for the first time. They’re at someone else’s house and he lays a towel down, and I remember thinking, “That’s a good idea.”

I read that, and I had conversations without shame with my grandmother. I remember asking my grandmother, “Nana, what’s an orgasm?” And I remember exactly: she was standing at the stove cooking matzo ball soup. She looked at me and she thought about it very seriously as she told me that it was like a tickling feeling that was better than any other tickle and you don’t want it to stop. I remember thinking, “Great answer.”

In her library at home, I came across so many books when I was a kid, and whenever I had a question, she would answer them. And that, I think, is the difference. I spoke with a grandmother at an event that you and I did recently. She said, “How do we get the porn off the internet?”

I responded, “You’re not going to get the porn off the internet, but you could have a conversation before your kid intersects with porn, to explain what porn is and why you think they shouldn’t be looking at porn and offer them other resources that are more age appropriate.” Arm them with knowledge. I think that we conflate ignorance and innocence in a very dangerous way.

Is there anything else you’d like to say to PEN America’s audience of writers and lovers of literature?

Every generation says, “We’re living through such challenging times, such divisive times.” This is one of our moments to say that and feel those things. As much as I want us to be gentle and listen to our own stories, and as hard as it is to do that with people whose perspectives are different than ours, we want all this great diversity of literature because of our uniting belief that speech should inherently remain free. Sometimes that means we have to be uncomfortable. And that’s okay. It’s okay to be uncomfortable. I just hope that our community can come through the current challenges intact and strong.

Elana K. Arnold is the author of critically acclaimed and award-winning young adult novels and children’s books, including the Printz Honor winner Damsel, the National Book Award finalist What Girls Are Made Of, and Global Read Aloud selection A Boy Called Batand its sequels. Several of her books are Junior Library Guild selections and have appeared on many best book lists, including the Amelia Bloomer Project, a catalog of feminist titles for young readers. Elana teaches in Hamline University’s MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults program and lives in Southern California with her family and menagerie of pets.

Hear From More Members

Ali Velshi on Reading as an Act of Resistance

Megan Fernandes | The PEN Ten Interview

Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond | The PEN Ten Interview

Andrew Ridker | The PEN Ten Interview

In a way, the structure of the novel reflects one of its primary themes: the desire to break away from one’s family, and the bonds that invariably pull one back.