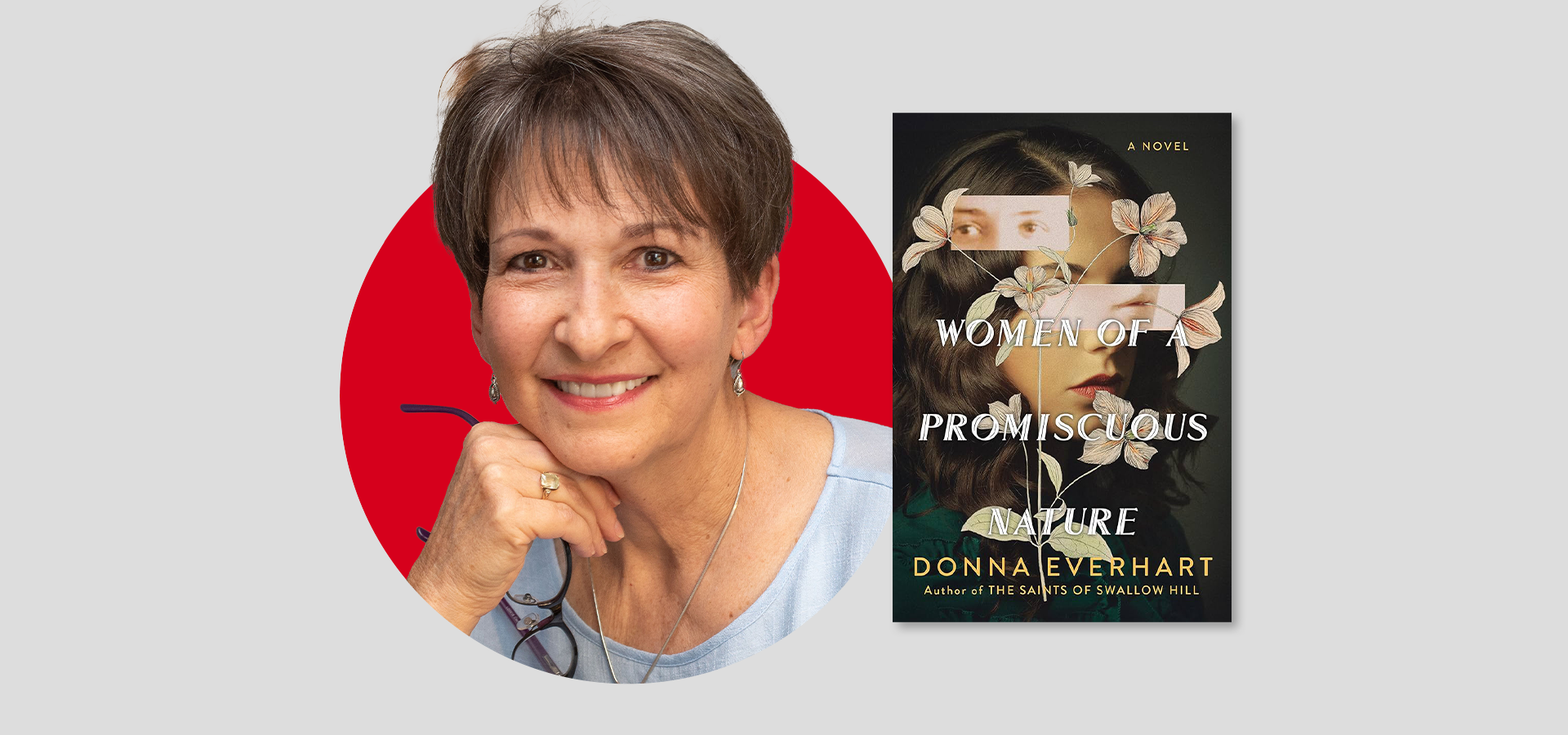

Donna Everhart | The PEN Ten Interview

Inspired by the American Plan, a government program that sought to control women’s bodies and sexualities during the first half of the 20th century, Donna Everhart’s Women of A Promiscuous Nature is a historically rich narrative with deeply modern resonances (Kensington, 2026). The novel follows Ruth and the women she meets at the State Industrial Farm Colony, all of whom are forced to undergo “training” to become pure and upstanding members of society.

In this week’s interview with Erica Galluscio, digital production manager, Everhart describes her exhilarating research process, the complicated role of domestic labor in the novel, and the Southern literature that continues to serve as a source of inspiration for her. (Bookshop; Barnes & Noble)

Women of a Promiscuous Nature explores a very complicated moral question: can institutionalization benefit someone who is suffering in their real life? Why did you explore Stella’s enjoyment of her time at the Colony?

Stella’s character certainly offers a perspective some readers might find surprising. She was removed from a toxic home environment where she wasn’t safe. She struggled to get enough to eat, had parents who were “checked out” and, in one case, abusive. Despite the nature of her detainment and what she experienced while at the Colony, it at least offered her protection from the untenable circumstances of her home life.

Even so, writing her part was tricky. Sometimes the easiest way to manage an uncommon or morally complicated angle is to anchor it in historical record. During my research, I found the case of a young woman who turned to prostitution at fourteen.

What I understood from the records is while she was imprisoned, she learned to read, write and to sew. Once released, she supported herself through sewing rather than sex work. It’s difficult to reconcile this outcome with the undeniable harm done to Stella and others, but that tension is exactly why I chose to include a character like her.

This novel isn’t your first work of historical fiction. What can modern readers gain from stories about the past?

By creating a narrative that brings history back to life, historical fiction gives readers the chance to experience a different time period and examine it through today’s moral, social, and cultural lens, especially if that history is difficult to digest. Being aware of shifts in thinking and actions over time has a way of adding perspective.

I like to think it’s helpful for readers to assess a character’s beliefs and choices as they navigate the challenges of their era, and then witness the consequences of those decisions. Historical fiction is like a rearview mirror in that we can see where we’ve been. Learning what came before us offers an awareness of events and issues we might not otherwise understand. It can foster empathy through context, or just as importantly, bring clarity about what we never want to see repeated again.

What was your research process like for this book? Was anything different about your process for this novel? Are there any habits you always keep the same?

When researching any novel, I’m much like a person with one of those metal detectors, constantly sweeping about from one resource to another for treasure, whatever it is, to fortify the history within a story. There wasn’t anything different about my research process for Women of a Promiscuous Nature except for the need to repeatedly verify and re-verify each fact I uncovered, almost as if I couldn’t believe what I’d read and I needed more proof that it was actually real.

When I first read about the Chamberlain-Kahn Act, or the American Plan as it’s also known, I remember thinking it was similar to the mass internment of Japanese-Americans during WWII. Under the American Plan, military, police, and public health officers were empowered to arrest any woman even suspected of having a sexually transmitted infection—or of being a “promiscuous” or “immoral” influence—often with no real evidence. Once arrested, women were forced to undergo invasive medical examinations. False positives for STI tests were common and women were indefinitely imprisoned without due process until authorities deemed them “cured.”

I was stunned that I’d never heard of women being controlled and punished in this way and that, despite being one of the largest and longest mass quarantines in U.S. history, the American Plan has largely been forgotten.

Historical fiction is like a rearview mirror in that we can see where we’ve been. Learning what came before us offers an awareness of events and issues we might not otherwise understand.

With such a rich ensemble cast, how did you decide which characters to follow? Why was it important to focus on Baker, an antagonist, along with your protagonist?

I wanted to represent as many historical angles as I could and I settled on Ruth, Stella, and Superintendent Dorothy Baker as accurate, if necessarily broad, representations of certain women impacted by these events.

There were many reasons women might find themselves at the North Carolina State Industrial Farm Colony for Women or any other detention facility across the United States. Ruth’s character personifies some of the more independent-minded thinking young women of the time, the ones who might have sought a life outside what society prescribed. I read about women being detained for walking to the post office, eating alone, or otherwise appearing to behave in “questionable” ways. Ruth is seen as outside the norm because she chooses to live independently and support herself by working at a diner. She represents the women who felt that they had a right to live in the manner they chose.

Meanwhile, Dorothy Baker symbolizes many reformers of the era. Probably the most unsettling aspect of individuals like her is that they believed in what they were doing. Like Baker, many Superintendents were self-righteous and bent on correcting what they viewed as immoral or degenerate. Their success — as well as their budgets and job security — depended on “reforming” inmates.

Given Baker’s background in the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, an organization that raises awareness of the contributions made by women as well as promoting civic service through volunteering, I believe Baker and others like her were products of their time.

The presence (or lack thereof) of men in the novel was striking. There are two male characters — one pulling the strings behind the scenes and the other providing a faint beacon of hope. What do these two male figures represent for the women?

These characters show another distinct separation in mindset, similar to Baker and the inmates. Dr. Woodall, as a Board chairman for the North Carolina State Industrial Farm Colony, epitomizes government oversight, overreach, and enforcement of authority, while Stanley Newell, as a local lawyer, signifies the possibility of justice as well as freedom.

Can you talk about the importance of domestic labor in the novel? I found it interesting that cooking, cleaning, and laundering were so prevalent — both as opportunities for connection between the women while also functioning as their punishments.

Given the timeframe of the novel, domestic duties were seen as a traditional role for women. Many women sent to the Colony or other facilities were viewed as negligent or “slovenly” with regard to the upkeep of their homes. “Training” them for domestic labor was seen as necessary so when they were released, they could do domestic work for pay, or if married, run an “efficient” household.

And the final blow? The domestic duties to which women were sentenced were also what allowed the states to run the facilities — through the women’s unpaid labor.

Any group forced to spend large amounts of time together will develop some degree of camaraderie. In this case, cooking, cleaning and laundry became gateways for my characters to form meaningful relationships and build community in a place that could sometimes devolve into competitiveness and seeking favoritism. Ruth’s cooking, for example, becomes an act of care and nurturing toward her fellow inmates.

Any group forced to spend large amounts of time together will develop some degree of camaraderie. In this case, cooking, cleaning and laundry became gateways for my characters to form meaningful relationships and build community in a place that could sometimes devolve into competitiveness and seeking favoritism.

What contemporary event or societal moment inspired you to write about women’s autonomy and institutionalization?

This question makes me think of Margaret Atwood’s response when she was asked how her idea for The Handmaid’s Tale came to her. She spoke about real-world events, such as what was happening in Iran or with the Klan, where women’s bodies were controlled by the patriarchy. She said she’d gathered newspaper articles that demonstrated that her “speculative fiction” was not so speculative at all.

When I begin searching for something to write about, even while acutely aware of current events, I allow myself to hunt for that one historical detail that makes my heart race. Discovering a neglected or overlooked piece of history is gold. And if it also echoes modern realities, I feel fortunate to be able to shine a light on it.

That’s what happened here. It was a fluke of a find, and my own reaction to it compelled me to write, with both urgency and caution. I wanted to make sure I wrote an accurate, yet compelling and respectful story, while exposing this important piece of history.

Stories tackling topics such as the ones in Women of a Promiscuous Nature are winding up on banned book lists all over the country. How does it feel to write books that are “objectionable”?

It’s incredible to think this type of story could end up banned. I wasn’t setting out to be audacious. What’s true is that history itself is often offensive in its quiet, factual reality.

What about the South, Southern women, and Southern literature keeps you inspired?

Ah, the South. I do love it, and I love being a Southerner. I love that it can provoke questions about who I am even before someone knows me at all. Maybe that love is one of my biggest inspirations, but so is my desire to study and untangle our complicated history, culture, and way of life.

Our thorny history is why I write looking backward instead of forward. Sometimes it’s personal. I’ve witnessed things in my own childhood that would provoke outrage today, like the KKK billboard (“Welcome to KKK Country!”) once visible on Interstate 95 near Smithfield, North Carolina, which later informed my third novel, The Forgiving Kind. I’m also drawn to obscure histories, such as the brutal turpentine industry depicted in The Saints of Swallow Hill.

Strong women, past and present, are everywhere in my life and an enduring source of inspiration. I often draw from those whose quiet strength left a mark on me, from the tender-hearted kindness of my Aunt Suzy, to the Steel Magnolia-like persona of my paternal grandmother, Lillian Mae Holliday Davis. She was the sort of Southern woman I like to write about. Quiet, unassuming, and rather solemn, she had more than her share of trouble in life. My grandfather wasn’t an easy man to live with. He was a bootlegger and something of a scoundrel who drank what he made to excess. She left him, worked outside the home, and refused to institutionalize my aunt with Down Syndrome — all very uncommon choices in the early 1960s. This novel is dedicated to them.

Finally, reading Southern literature is and always will be my mainstay. I have so many fine Southern writers I can look up to, not only for what they chose to write about, but how they wrote it. Flannery O’Connor, William Faulkner, Cormac McCarthy, Kaye Gibbons, Dorothy Allison, Robert Morgan and many others have shed light on this region, and perhaps helped those who aren’t from here understand the people, the history and way of life a little bit better.

Discovering a neglected or overlooked piece of history is gold. And if it also echoes modern realities, I feel fortunate to be able to shine a light on it.

Without spoiling too much, do you think readers will find the ending of Stella’s arc hopeful? How about Ruth’s?

It might be interesting to know I originally planned a very different ending for Ruth, while Stella’s arc was settled about halfway through the writing process. Stella’s ending felt logical and true to what her character needed.

Ruth’s ending, on the other hand, changed because I felt my original plan would misrepresent history. I could have given her a certain moment of triumph, so to speak, but that would’ve done a disservice to the reality faced by so many women of that time.

Donna Everhart is a USA Today bestselling author known for vividly evoking challenges of the heart and the complex heritage of the American South in her acclaimed novels Women of a Promiscuous Nature, When the Jessamine Grows, The Saints of Swallow Hill, The Moonshiner’s Daughter, The Forgiving Kind, The Road to Bittersweet, and The Education of Dixie Dupree. A finalist for the Southern Book Prize, she is the recipient of the prestigious North Carolina Society of Historians Award of Excellence, the SELA Outstanding Southeastern Author Award from the Southeastern Library Association, the Lucy Bramlette Patterson Award from the General Federation of Women’s Clubs of North Carolina, and her novels have received a SIBA Okra Pick, a LibraryReads selection, two Indie Next Picks, and three Publishers Marketplace Buzz Books selections. Born and raised in Raleigh, she has stayed close to her hometown for much of her life and now lives just an hour away in Dunn, North Carolina. Please visit her online at DonnaEverhart.com.