‘Writing offered me catharsis and a chance to grow as a person’

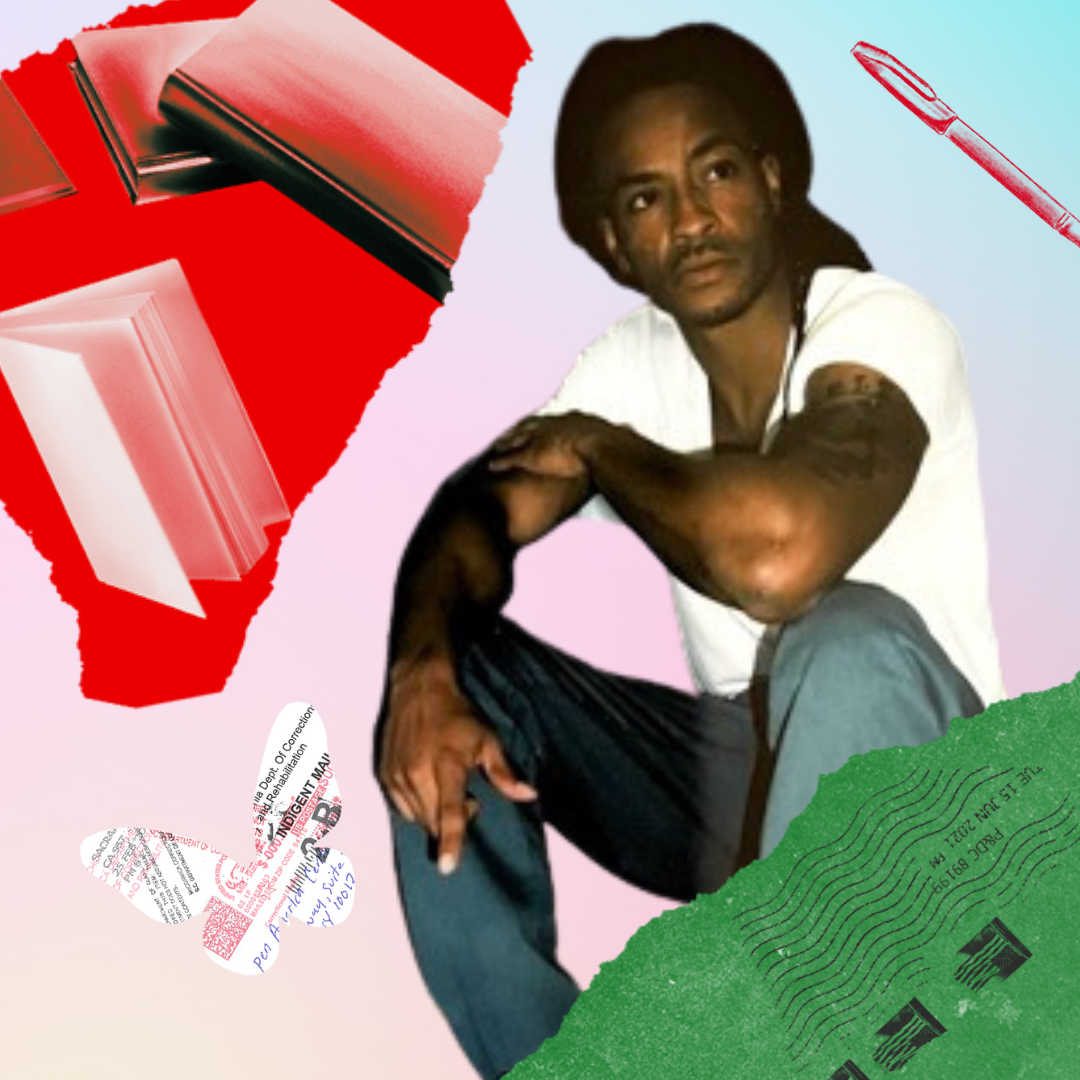

After nearly two decades in prison, Derek Trumbo Sr. walked out of Kentucky’s Northpoint Training Center in April. Though he had never tried his hand at writing before he was incarcerated, he left as an accomplished author, essayist, and playwright.

Trumbo is one of 21 writers featured on Incarcerated Writers Bureau, a groundbreaking digital resource that PEN America launched today. The website provides literary professionals with resources on how to work with incarcerated writers, a database to which they can add calls for submissions open to writers in prison, and the featured profiles of incarcerated and recently released writers.

While at Northpoint, Trumbo won numerous PEN America Prison Writing Awards, each time earning a spot in PEN America’s Prison Writing Mentorship Program. He began a column for the nonprofit news website Prism, “Never Eat the Candy on Your Pillow,” where he shared stories from and reflections on his life in prison. Following his release, Trumbo switched the focus of the column to his reentry process and began preparing a collection of short stories for publication.

In this interview, we spoke to Trumbo about how PEN America’s resources have and will continue to open doors for writers behind bars. IWB, he told us, could facilitate real change — “not just in the judicial system and how it works but also in the [literary] industry and in the minds of the people that we return home to.”

What did PEN America’s Prison Writing Mentorship Program, and writing more generally, afford you while you were still in prison?

Writing offered me catharsis and a chance to grow as a person. It allowed me to explore so many different facets of myself that I had never had the chance to consider because of my upbringing. I grew up in the West End of Louisville, which is really bad. It’s nothing but gangs and drugs. I never thought I could write. I didn’t think I had the ability to tell stories. I spent most of my life being told, pardon my French, that I was never going to be shit, never going to amount to shit.

In incarceration, I was given the opportunity to sit down and, without the distraction of life, figure out what was going on. Writing, specifically the writing process, but more importantly PEN America, gave me a chance for hope, gave me something to look forward to. Honestly, when I first submitted, I didn’t think I had a shot. I didn’t even think I’d get a response.

Can you elaborate on how the awards affected the way you thought about your time in prison and your future after it? Did they create any tangible change for you?

I mean, just the prospect of the prize money. Nobody really cared that I won, except for maybe a few key prison staff. But among the inmate population, people were like, ‘So?’ ‘And?’ ‘How much does it pay?’ And then I’d tell them, back then, it was 200 bucks if you won the grand prize. And they’re like, ‘$200? Wow.’ You know, I was making 80 cents a day for eight hours of work, so I’m living off of $16 a month. $200 is a lot. So the prize money was the motivation to work at the craft.

When I won for the first time, it made me look at everything like, ‘Maybe I’ve got a little bit of skill. Maybe I need to work at this more.’ Because, yes, I’ve heard that there are starving artists everywhere and that writers really don’t make a lot of money, but, at the time, I didn’t have any skill sets, so I was like, ‘Well, I can always write, and maybe somebody will care.’ So that gave me hope. The whole contest gave me hope.

What did you buy with the prize money?

More writing supplies. I bought a radio the first time I won, so I had something to drown out all the background noise. And I bought the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Stadium Arcadium. “Slow Cheetah” and “Snow” drowned out a lot of things.

Writing, specifically the writing process, but more importantly PEN America, gave me a chance for hope, gave me something to look forward to.

Were there other sources of hope for you while incarcerated?

Prison was hopeless for me. I spent years fighting my case, trying to get things back in court, and that was to no avail for a long time. The only hope I had was through my writing and the ability to communicate…through being recognized by PEN America.

They have a saying: ‘If you can’t change the people around you, change the people around you.’ The ability to communicate opened doors for me that were never open before. I realized I could verbalize and articulate everything that was going on within me and attract a new breed of people who also had the skill sets to do what I sought to do.

Who did you start attracting and how?

Not only did it allow me to physically change the people around me, but when people saw me grow as a person, it allowed them to aspire to want to have what I had. One of the guys that I grew up with would tell me — because in prison, there’s always conflict — he would tell me often that the people that were against me were against me because I had something they didn’t have, which was a sense of purpose. Writing gave me a sense of purpose, and then I was able to take that and give it to other people and inspire them to do the same.

What did that actually look like? Did you convince other people to start writing? To submit to PEN America’s Prison Writing Awards or to other writing contests?

Yes, I convinced quite a few people. Through PEN, I got some really good mentors who taught me how to critique without it sounding like criticism, and several of them gave me techniques that I could use when working with others. PEN got flooded by a lot of the people that I was mentoring. I worked with a lot of guys individually, and we had group settings where I led classes. I was also a part of a playwrights group that wrote 10-minute plays. … In those settings, I was able to take my abilities and put them to use, not just writing, but also mentoring and showing what could be done. It went from nobody at Northpoint winning PEN to us having a bunch of winners.

Who were some of the memorable mentors you met through the Prison Writing Mentorship Program? What made them so good?

My very last mentor, Emily Jon Tobias, opened doors to opportunities for me and went to bat for me. She’s like, ‘Hey, I think you should submit to this place. I think you should contact Haymarket books. I think you should do this and do that.’

Are you still in touch with her now?

Oh, yeah. I just spoke with her today. Me and Emily Jon, we stay in contact. We talk on the phone. We Zoom. We do it all. She is an amazing person who was able to use writing to help heal her wounds as well. She’s probably one of my best friends in the world.

Writing gave me a sense of purpose, and then I was able to take that and give it to other people and inspire them to do the same.

I know you were released in April. What have you been writing since then?

I write my columns for “Never Eat the Candy on Your Pillow.” I have a collection of short stories called Palpable Prisons. It’s a collection of short stories about prison, about the relationships that form in prison, the bonds between men who are struggling to adapt, not just to incarceration but to a new understanding of life. I’ve had a ton of rewrites, and I’m ready to start sending it out to interested agents and publishers.

I’m also working on several other projects that have nothing to do with prison. I’m doing screenwriting for several people. One writer has written an entire novel that she wants me to adapt into a screenplay. These are opportunities that never would have been possible without writing, but even more importantly, without me being able to say, ‘I’m a multiple-time PEN award winner.’ People look that up and go, ‘Oh?’ That gives me all the credibility I need.

How do you think the Incarcerated Writers Bureau will help writers like yourself?

There are a lot of creative people incarcerated and post-incarceration who have a lot to offer the writing world that has excluded them for so long. If the Incarcerated Writers Bureau could put incarcerated people in a position to meet the right people, then a lot more stories would be told with more authority.

I’m doing everything from the reentry level now, and a lot of people don’t know what it’s like from that particular slant. Being in a position where the IWB could connect someone like me to the right resources to get more stories out there, to tell the truth about how things are — perhaps that can influence change, not just in the judicial system and how it works but also in the [literary] industry and in the minds of the people that we return home to.