State policymakers have introduced at least 1001This analysis consists of legislation introduced through March 15, 2021. In the period since PEN America’s research herein, the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law has documented additional legislation introduced throughout the country. For the most up-to-date account of legislation, please see ICNL’s US Protest Law Tracker. proposals since June 2020 to reduce the scope of Americans’ right to protest, PEN America research finds.

By Nora Benavidez, James Tager, and Andy Gottlieb

Anti-Protest Proposals Index »

Our Methodology »

In the wake of the mass protests for racial justice sparked by the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, a flood of legislation has been introduced in statehouses across the United States that would restrict protest rights. From June 1, 2020, through March 15, 2021, state policymakers have introduced at least 100 proposals in 33 states. Anti-protest bills were being introduced at an alarming rate even prior to last year’s protests, but as a point of comparison, from January to May of 2020, PEN America identified only 15 such proposals. The rate at which such legislation is being introduced has significantly increased since the protests sparked by Floyd’s murder began.

The 100 proposals introduced since June 2020 primarily take aim at protest-related activity—that is, activities that arise naturally from participating in a protest or are likely to occur as a foreseeable part of protests—seeking to create new penalties or expand existing penalties for such activity. A smaller number of proposals incentivize greater police presence during protests. Only six of the 100 proposals have a Democrat as a primary sponsor.

The majority—73—of these proposals came in the wake of the January 6 Capitol Hill riot. But it would be misleading to conclude that these bills have been developed overall as a direct response to the Capitol siege. The continuity between anti-protest bills proposed before January 6 and those that came after strongly indicates that state legislators have been sticking to the same anti-protest playbook developed in response to the largely peaceful Black Lives Matter protests.2PEN America can identify only one bill that includes provisions conclusively drafted in response to the January 6 riot rather than in response to prior protests: Connecticut’s HB 6455, which would create the offense of “obstructing the legislative process.” Because this bill contains provisions that can be arbitrarily wielded against peaceful protesters, similar to other bills within this analysis, we have retained HB 6455 within our count of anti-protest bills. Many state legislatures also started a new legislative session in January, which accounts for the significant number of bills introduced since then. And based on existing research, there is reason to anticipate that even bills introduced on the pretext of responding to a right-wing insurrection are likely to be disproportionately enforced against movements led by people of color or focused on issues of racial and social justice.

These bills are part of a larger trend of anti-protest legislation proposed in recent years, which PEN America first documented in Arresting Dissent: Legislative Restrictions on the Right to Protest. That report was released on May 27, 2020, just two days after Floyd’s murder. In Arresting Dissent, PEN America found that many bills were seemingly or explicitly designed to target movements led by people of color, including Black Lives Matter protests and anti-pipeline protests often led by Native American communities; and the anti-fascist or “antifa” movement.

This pattern of bills motivated by legislators’ animus toward particular protest movements persists, but with more fervor and drastic consequences for would-be protesters. While the majority of demonstrations over the last 10 months have been peaceful, lawmakers have repeatedly played on fears of violence and disorder to introduce bills that severely undermine the right to protest.

The First Amendment explicitly lays out that Congress—and, by extension under the 14th Amendment, state governments— shall make no law abridging or limiting our right to assemble or speak freely. While the government may impose some regulations on the right to assemble, these regulations must be narrowly circumscribed.

The current slate of anti-protest proposals fails to narrowly regulate the right to assemble freely, and instead takes aim at many protected forms of speech as well as other constitutional rights. For example, the enlargement of the concept of “unlawful assembly” tilts the balance toward viewing protest as inherently criminal—something that fundamentally impacts First Amendment rights. Some proposals additionally implicate different constitutional rights. For example, at least 11 proposals would make people convicted of (or in one case, merely charged with) protest activity ineligible to receive public state benefits, raising obvious concerns about due process.

In seeking to create new crimes and steeper penalties for activity protected by the First Amendment, all of these proposals burden our right to freedom of assembly. The bills that do become law may lead to fewer people engaging in peaceful protests, as individuals weigh the risk of various sanctions—from large monetary fines, to 15-year prison sentences, to ineligibility for state benefits, or even the ability to run for office.

While this newest slate of bills is in many ways simply a continuation of previous trends, there are some signs that things are getting worse.

Three key findings of PEN America’s research

1. At least 100 anti-protest bills have been introduced across 33 states since George Floyd’s murder.

In Arresting Dissent, PEN America documented how state lawmakers introduced 110 anti-protest proposals between 2017 and 2019. Now, in the past 10 months alone, we have observed the introduction of 100 such bills—a staggering escalation.

Of these 100 proposals, only Tennessee’s HB 8005, Kansas’ SB 172, Arkansas’ HB 1321, Florida’s HB 1, Oklahoma’s HB 1674, and Alabama’s SB 152 have become law, but 64 bills are still active in their state legislatures. Another 30 have not moved forward. The states that have put forward the largest numbers of anti-protest bills since June 2020 are Oklahoma (12), Virginia (11), Minnesota (7), Ohio (5), Indiana (5), Missouri (5), Alabama (5), Iowa (4), Mississippi (4), Tennessee (4), and Texas (4).

Our Anti-Protest Proposals index features a summary of each bill. Key provisions that appear within multiple bills include: 1) creation of new crimes like “unlawful assembly”, 2) steeper felony penalties for existing misdemeanor offenses such as obstructing traffic, 3) penalties to strip eligibility to receive public state benefits from people convicted of certain protest activity, and 4) immunity for drivers who hit and even kill protesters.

Across the board, these proposals squarely threaten Americans’ rights by raising the potential costs of engaging in peaceful protest, an activity protected by the First Amendment. The bills often use vague terminology for concepts like “unlawful assembly,” which would afford police wide discretion to determine what constitutes criminal activity—discretion that evidence shows is likely to be wielded in biased or arbitrary ways.

A growing set of proposals also seeks to incentivize heavier police presence at protests. In Georgia, for instance, SB 171 sought to make local governments civilly liable for any damages resulting from their failure to “provide reasonable law enforcement protection during a riot or unlawful assembly.” In the wake of the past year’s Black Lives Matter protests against excessive use of force by police, and against a backdrop of widespread calls for policing reform, such measures come across as both a culture war broadside and an intentional effort to force a more aggressive police response to protests.

2. There has been a significant rise in “kitchen sink” bills: proposals that contain at least three or more distinct anti-protest provisions, including criminalizing protest activity, shielding counter-protesters, stripping protesters of public benefits, and others.

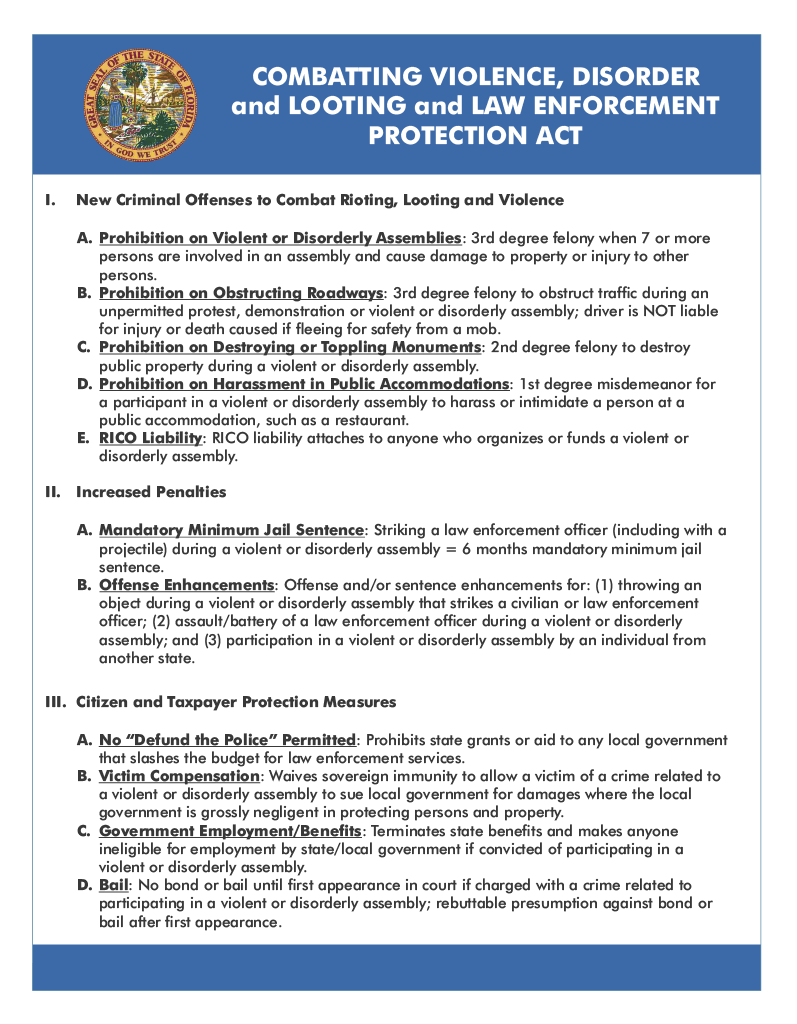

We define “kitchen sink” bills as those that aggregate at least three different anti-protest provisions into one overarching bill. Of the 100 proposals introduced since June 2020, we identify 29 of them as “kitchen sink” bills. Florida’s originally introduced Combatting Violence, Disorder and Looting and Law Enforcement Protection Act and Tennessee’s HB 8005 have been the most consequential such proposals, serving as a template for copycat bills in other states.

In Florida, Gov. Ron DeSantis introduced an influential anti-protest proposal in September, invoking “professional agitators, bent on sowing disorder and causing mayhem in our cities,” “crazed lunatics,” and “scraggly-looking antifa types,” and implying that protesters were being funded and organized by external forces—a common rhetorical tactic for discrediting protest movements. That bill has inspired over a dozen copycat proposals. Under the proposed Combatting Violence, Disorder and Looting and Law Enforcement Protection Act (Combatting Violence Act), which received vocal support from Republican state legislative leaders, the governor included 11 different measures that could be used to punish protest-related activity, including:

- Making blocking traffic during an unpermitted protest punishable by up to five years in prison;

- Making destroying or toppling monuments during a protest deemed to be a violent or disorderly assembly punishable by up to 15 years in prison;

- Stripping anyone convicted of “disorderly assembly”—a vague term that could easily be applied to a range of constitutionally protected protest activities—of the ability to receive public assistance benefits, such as unemployment, or to hold a government job;

- Providing a measure of legal immunity for drivers who hit demonstrators who are obstructing traffic during an unpermitted protest;

- Opening municipal governments to lawsuits if they are “grossly negligent in protecting persons and property” during anything that is deemed a violent or disorderly assembly, increasing the incentives for city leaders to direct a heavy-handed police response to demonstrations.

Some members of the legislature pushed back on the claimed need for this legislation. Noting that Florida’s existing laws already punish violence or property damage, Republican state Senator Jeff Brandes said it was unclear why the state needed new legislation, commenting: “While I agree we have to support law enforcement 100 percent, we also have to recognize the right afforded to citizens to peacefully protest.” Democratic state Representative Anna Eskamani stated, “You already have laws on the books to address vandalism, to address looting. We know this has nothing to do with public safety. It will lead to the arrests of more Black and brown people.”

A pared-back version of the Combatting Violence Act was introduced in both the Florida House and Senate (as HB 1 and SB 484) in January. The legislation makes blocking traffic punishable by up to 15 years in prison, creates vaguely defined offenses relating to riot and so-called “mob intimidation,” makes destroying or demolishing a memorial a second-degree felony, offers a measure of legal immunity to anyone who injures protesters convicted of riot, and opens municipal governments to lawsuits if they interfere in providing “reasonable law enforcement protection during a riot or unlawful assembly.” On April 15, 2021, the bill passed both chambers. On April 19, DeSantis signed the bill into law.

Aspects of the original, further-reaching September proposal appear to have inspired copycat proposals across the country. Legislators in 15 states—Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, New Jersey, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Utah, and Washington—have proposed 21 separate bills that borrow from the language of the original Florida Combatting Violence Act.

Some of the bills seemingly inspired by the Florida proposal attempt to go even further than the original. For example, Michigan House Bill 6269 sought to revoke public assistance benefits for one year from protesters charged with (not convicted of) looting or vandalism in connection with civil unrest, and also would have mandated a referral to Child Protective Services for indicted protesters who brought their children with them to a demonstration. House Bill 6269 has died in committee—yet, this is only one of at least 11 recent bills that have sought to strip indicted or convicted protesters of their eligibility for government benefits.

In Indiana, HB 1205—which remains pending in the state’s House of Representatives—seeks to strip existing immunity from government entities and employees who fail to enforce laws relating to unlawful assembly. The bill would make camping on state capitol grounds a Class A misdemeanor and broaden the definition of unlawful assembly to include at least three people engaging in “tumultuous conduct,” while making tumultuous conduct a felony when participants are masked or it results in property damage. And, HB 1205 bars local governments from defunding law enforcement agencies, an increasingly common provision in these “kitchen sink” proposals.

Another example is Ohio’s HB 109, which would create the felony crime of “riot vandalism,” defined to include damaging monuments or memorials and would increase penalties for causing property damage during a riot. It would also create the misdemeanor crime of harassment in a “place of public accommodation”—a category usually applied to a wide variety of locations such as restaurants, parks, and stores—and make it a third-degree felony to obstruct traffic during a riot or a “protest or demonstration for which no permit was issued or for which the scope of any issued permit was exceeded.” Such provisions could easily be used, for example, to punish protesters who step into the street during a protest where turnout exceeded expectations. In a tactic repeated in at least seven other bills, HB 109 would also extend racketeering offenses to apply to the act of providing “material support”—a notoriously vague term—to demonstrations deemed to be riots. Given the vagueness of the language, such a provision could potentially be used to hold nonprofits that offer “Know Your Rights” trainings for protesters, for example, criminally liable if training participants then joined a protest that was deemed a riot.

Meanwhile, in Tennessee, legislators responded to Black Lives Matter protesters camping out at the state capitol by fast-tracking a bill, HB 8005, to make camping on state grounds, such as the state capitol, a Class E felony, punishable by up to six years in prison. It is worth noting that any Tennessean convicted of a felony also automatically loses their right to vote. The law also increases penalties for interfering with a meeting of the legislature (even by “verbal utterance”), minor vandalism (such as chalking) of government property, and blocking streets. It requires that people arrested under these charges be held for at least 12 hours without bond. And the new law appears to have influenced similar bills in Kentucky, South Carolina, Arkansas, and Oklahoma, as well as two separate bills in Indiana, all of which contain similar provisions.

The sequence of events leading up to the Tennessee law itself helps illustrate PEN America’s concerns that these bills are being motivated by bias against specific protest movements. Black Lives Matter protesters began camping out at the Tennessee State Capitol in June 2020, demanding to meet with legislative leaders and the governor. Instead, Gov. Bill Lee decided to convene a special legislative session in August 2020 to pass HB 8005, alongside emergency pandemic-related bills. The Tennessee General Assembly met and deliberated for just three days, the bare minimum allowed. Supporters of the legislation seemed unable to offer any rationale for this urgency. For example, when asked if any officers had been injured during protests at the state capitol, the bill’s sponsor, House Majority Leader William Lamberth, could not furnish any examples.

Instead, some comments from HB 8005’s supporters appeared to offer a different rationale for the urgent legislation: their personal anger and discomfort over the protests. Sen. Kerry Roberts, who voted for the bill, recalled being shouted at by protesters as he walked down a sidewalk, saying, “The thing is, what I wish I could convey to people is that it’s really hard to be sympathetic to what someone is saying when they are yelling at you, when they’re trying to shame you, when they’re calling you names and so forth.” Roberts went on to clarify that he was not referring to any fears over his safety, but rather that the protests had made him feel “extremely uncomfortable.” Lt. Gov. Randy McNally, who supported the legislation, similarly complained of people “knowingly thumb[ing] their nose at authority.” One legislator who opposed the bill, Rep. Jason Hodges, stated, “We seem not to worry about protesting when white people show up with AR-15s, but when Black people show up with signs we try to pass legislation… maybe that’s why they’re out there in the first place.”

“We seem not to worry about protesting when white people show up with AR-15s, but when Black people show up with signs we try to pass legislation… maybe that’s why they’re out there in the first place.”

—Tennessee State Rep. Jason Hodges

In Kentucky, which witnessed some of the most sustained demonstrations in the country in the wake of Breonna Taylor’s murder, legislators proposed SB 211, a particularly loaded “kitchen sink” bill incorporating provisions from both the Florida proposal and the Tennessee law. It includes similar clauses on public assistance benefits, camping on state property, traffic obstruction, and civil liability for local governments. At the same time, it would classify pointing a light at a police officer as assault in the fourth degree. Taunting a police officer with “offensive or derisive words” would be classified as a Class B misdemeanor; if committed during a riot, this would mandate a prison term of at least three months, along with loss of public benefits for three months. SB 211 managed to pass the Kentucky Senate, but failed to pass the House before the most recent legislative session ended.

3. The penalties for protest are becoming harsher and farther-reaching, affecting one’s eligibility for public assistance and even the ability to run for office.

In Arresting Dissent, PEN America identified one overarching theme of anti-protest proposals: efforts to redefine acceptable protest by expanding the scope of illegality for protest-related activity. We found four common bill provisions: (1) expanded definitions and penalties for conduct deemed to be riot, criminal trespass, obstruction of traffic, or a similar offense; (2) imposition of costs on protesters for unlawful conduct; (3) criminalization of constitutionally protected activity that may occur in relation to a protest, such as wearing masks; and (4) shielding public or private actors from liability for harm caused to protesters. Many of these elements are present in the newest spate of proposals, which continue to impose financial sanctions and/or prison time for targeted protest-related activity.

Yet, not only are new bills proliferating at a faster rate and featuring a wider array of provisions, the penalties for protests are also becoming harsher and farther-reaching.

At least 11 proposals contain provisions to make indicted or convicted protesters ineligible to receive state benefits such as health care, unemployment, or even school scholarships. Arizona’s HB 2309 seeks to make people ineligible for public assistance benefits if they were convicted of “unlawful assembly.” Minnesota’s HF 466, still pending, would make anyone convicted of a criminal offense related to a protest ineligible for government aid, including student loans, unemployment benefits, food stamps, and medical assistance. Missouri’s SB 66, also pending, would make local government employees convicted of unlawful assembly or riot ineligible for benefits such as health insurance, sick leave, and disability, retirement, and death benefits.

Other proposals like Ohio’s HB 109 and Oklahoma’s SB 806 would extend racketeering offenses—most commonly used against organized crime—to apply to riots. This would open the door for peaceful protesters to be punished for crimes committed at a protest that they themselves did not actually commit; Ohio’s bill even extends racketeering charges to apply to those providing “material support or resources” for riots. Under Ohio’s Revised Code, this “material support” includes training—opening the door to potential criminal liability for nonprofits offering “Know Your Rights” trainings, if a subsequent protest were to turn violent. Kansas has passed SB 172, extending racketeering charges to cover “critical infrastructure” offenses. As PEN America previously noted in Arresting Dissent, these types of “critical infrastructure” bills appear to be largely aimed against anti-pipeline activists and other environmental protesters.

Finally, several proposals would limit the ability of a convicted protester to hold state employment or run for public office. In Utah, SB 138 died in committee, but it sought to make anyone convicted of “felony riot” ineligible to hold public employment or receive government benefits for five years. Likewise, in Alabama, HB 133 remains pending and would increase criminal and civil penalties for riot and inciting riot, establish the crime of aggravated riot, and bar anyone convicted of riot from holding public office.

Conclusion

In the wake of the racial justice protests of the past year, legislators around the country have responded by seeking to criminalize protest-related conduct, raise the potential costs for protesters, and degrade Americans’ rights to peacefully assemble, make their voices heard, and call for change. Just as we noted in Arresting Dissent, in some cases legislators even acknowledge that they are aiming these bills at specific protest movements. These bills, collectively and individually, are misguided, unwise, and pose a direct threat to Americans’ constitutional rights.

At a moment when many of the norms and institutions of American democracy are being tested, the right to protest remains a fundamental form of public expression. In recent years, public protests have played an important role in helping to shape public discourse around critical policy and societal questions. Since June of 2020, those protests have largely focused on advancing racial justice and reckoning with legacies of racism in the United States. The number of bills attempting to restrict freedom of assembly at this particular moment smacks of a deliberate attempt to constrain that discourse, and it demands our attention as a fundamental threat to free expression.

Research Methodology

Consistent with the methods previously used in our May 2020 report Arresting Dissent, PEN America conducted an analysis of all relevant proposals introduced in state legislatures between June 1, 2020, and March 15, 2021. We confined the subject of these bills to those primarily aimed at placing constraints on the freedom of assembly, and we developed a database of bills meeting this description, alongside a typology of anti-protest bills.

The paper reflects a comprehensive review of the bills themselves, along with news articles and legislative tracking information. It draws heavily from the US Protest Law Tracker developed by the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL), which monitors and regularly updates state and federal proposals related to protest restrictions. The report includes, as its Appendix, a comprehensive list of 100 bills proposed during the period studied.