This Q&A is part of a series that will include interviews with journalists and experts who regularly handle disinformation. The interviews will appear regularly through the election and beyond to highlight best practices, insights, case studies and tips. Our goal is to provide a resource to assist reporters and community members through the news events of 2024.

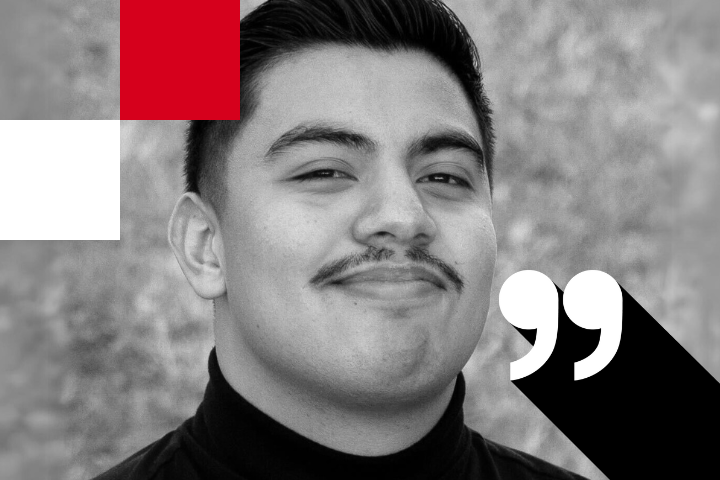

David Silva Ramirez knows disinformers try to fill gaps in information for people who might not understand the inner workings of their local government. As civic editor for the nonprofit Dallas Free Press, he wants to pull back the curtain for Dallas residents on how decisions are made, putting them in the room with decision-makers: He helped to launch the Documenters program, which pays and trains Dallas residents to attend and take notes at public meetings before publishing the results.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you tell me about the work you do with the Dallas Free Press, specifically with the Dallas Documenters program, but really, anything you want to touch on?

Yeah, of course. So with our Documenters program, essentially, our main focus is to recruit and train residents to attend public meetings, particularly public meetings that maybe don’t have a lot of coverage, maybe some of the smaller subcommittees and commissions. We work with newsrooms in Dallas and ask them, “What meetings are you guys at? Which meetings would you like for us to be at?” And we provide a lot of information for them that they sometimes include in their stories.

But it also provides an opportunity for residents to understand the public meeting process or the local civic process a lot better – and get paid for it. We do pay them for their time. And we send out a newsletter every few weeks to give people some insight on some of the meetings that might not be getting the biggest coverage, or maybe just some of the items in the bigger meetings that might have been forgotten or are not prioritized by other newsrooms because of their capacity. The Dallas Free Press has a focus in West and South Dallas. We recruit and train people from all around Dallas, but we do have some extra recruitment efforts in West and South Dallas, which are predominantly undervalued neighborhoods. So we try to get a lot of people who might not necessarily have the opportunity to be engaged with local government. And again, providing that payment allows us to really value their time.

That’s such a cool way to get people involved and also help out newsrooms. How did the paper decide to do this? Why did you all think it was important?

It is part of a national program. I’m not sure if you’re familiar with the Documenters network, but they started in Chicago in 2018 with City Bureau, which is also a nonprofit newsroom, and they’ve been growing ever since – they’re in Detroit, they’re in Philly. We’re part of the Dallas Free Press but we’re also part of the Documenters network.

The coverage of public meetings in major cities is an issue, it seems, everywhere. It seems nationwide there are not enough newsrooms or enough reporters to keep up with all the public meetings, act violations and things like that. That’s where I think the initial interest of this program originated. And then, obviously, getting residents to be the ones to participate is such a dual way to increase that coverage at these meetings, but also to incentivize local engagement from residents. If you’re targeting or trying to go to specific neighborhoods, you can try to promote that in neighborhoods and communities that may have not had any previous incentive to engage with the local government process. Hopefully it really creates an ecosystem where journalists, residents, local officials and community leaders are aware that people are watching and this system – that liberal democracies – can work how they should.

A lot of our work at PEN America is focused on disinformation and what journalists can do about the spread of disinformation, and I think local and civic engagement is such a big part of that. How do you think the Documenters program helps combat the spread of disinformation and what have you learned from this program?

Disinformation is really effective in providing an answer to things that may seem confusing or far away to a lot of residents, things that seem as if there are elites or certain people that make those decisions that affect your day-to-day and there’s no way that you’re impacting this. I think that by engaging in local government, you start to realize how much your city council’s decisions have an impact on your everyday life, and you start to realize how much you can impact that. It kind of provides the connection point between some of the services that you have, some of the resources, some of the decisions that are being made, and you’re able to connect that with a person and you know what to do about it. You understand that if there are enough people who are upset about a zoning change, it will be – at the very least – considered.

Once you’re at that local level, your individual impact is so much higher. That kind of takes the veil away and allows residents to understand how they can get involved with representative government. It takes away the talking points of a lot of misinformation – that there are things you can’t impact, that there’s a group that’s really running things. And when you look at just how human local government can be, you can see your city council person and say, “Oh, this is a person that doesn’t really represent me, I want to vote them out,” or, “This is a person who does represent me, but they’re making this decision and I want to let them know that I don’t agree with that or at least let them know that I’m watching.” That really takes away a lot of that opportunity for misinformation to seep in.

How do you think that journalists fit into this picture? How do you think that residents and journalists can work together to mitigate that spread of disinformation and keep local officials accountable?

This is kind of a bigger issue with our business and the way that it’s working right now – it really doesn’t incentivize (reporters) staying in one place for a long time. A lot of local newspapers are undervalued, maybe they don’t pay their people well. So it really makes it difficult for reporters to stay in one place and grow internally. But despite that, one thing journalists should definitely do is try to engage with people who aren’t part of the local government or the civic process and listen to what concerns they have, what issues they’re dealing with that directly connect to their local government.

And then for residents, I think not being afraid – and obviously, this is gained by trust – to tell people, “Oh, this is what I heard.” Even if it’s at the risk of being wrong, that still gives people an insight of what misinformation is being spread around, because it can be misinformation about national or international things or it can be misinformation about a decision that was made at a local school. If residents have the ear of journalists, they can say, “This is what we’re hearing and a lot of people believe this.” The journalists can then decide to write a story about that, or provide information or break down the facts about what’s really happening with something, or ask the people in power what they’re actually doing. Really kind of honing into these communities, I think that’s the solution to combating a lot of this misinformation. Again, it’s really difficult to do within the structure of our industry right now, but that’s ideally what I hope would happen.

I’m glad you mentioned trust, because I wanted to ask: How do you think journalists can rebuild trust with their communities, specifically when covering the spread of false information, which breeds mistrust?

What people in management at the Dallas Free Press like to say is, “show up, and keep showing up.” One of our program managers, she’s from West Dallas and will often say, “Have we been out in the community, have we gone and just let people know that we’re there?” And for things that are not just stories or for things that are not just something negative happening or people being upset, being there regularly has been really helpful for us. I would imagine that can be difficult for some beats in newsrooms … it’s kind of hard to think about it in terms of big newsrooms, like the Dallas Morning News and the (Fort Worth) Star-Telegram. It’s really hard to ask a reporter that might be chasing ambulances to take the time to go to a safety meeting.

Yeah, it’s definitely a resource issue.

So maybe the answer is a little bit more complex and more complicated, where we really need to rethink our industry and the positions and the beats that we do, and the way we get our news, the way that we get our information and then write the news. I think it would really require an upending of the way that we view journalism and a change from traditional journalism. I’ve seen that happen, with City Bureau starting the Documenters network, and a lot of those partner newsrooms are nonprofits, the Dallas Free Press, and other nonprofit newsrooms in Texas that are really trying to do things differently. I personally do think that’s the future of good journalism – that’s why I took this job. Really rethinking how we do what we do and allowing ourselves to be connected to the communities that we cover is a solution.

What tips do you have for newer journalists entering the field and navigating how rapidly false information spreads? Specifically those who work at local papers, what advice would you give them?

I would say to meet people where they are. Being dismissive, even when people are completely off base, it’s just going to alienate you from them and them from you. You’re just not going to get there. It’s okay to call people out when they are wrong about something, but I think you can’t even do that until you listen. That means listening to all types of people from all walks of life, all types of theories, and all types of different agendas and priorities. That can be daunting, and that can be exhausting, and that can sometimes drive us a little crazy. But I think meeting people where they are really allows you to humanize people.

Before I took this job, I was a racial equity reporter and before that I was an education reporter at the Star-Telegram, and I was covering a lot of the anti-CRT (critical race theory) protests during Fort Worth ISD (Independent School District) board meetings. There were some people who were politically taking advantage of the situation, maybe bad actors, people with certain agendas, wanting to get elected or wanting to gain some kind of influence. But a lot of the people there were just parents who were maybe misunderstood, or were going into it with, from their perspective, the best of intentions. For me personally, it was very interesting to come to that realization, but that really didn’t happen until I was like, “Okay, no one’s talking to me, what if I just try to approach this a different way and try to meet people a little bit more where they are?” And I think that allowed for more grounded conversations and hopefully more effective reporting. That happens sometimes here, where a Documenter will go to a meeting and somebody will say something very convincing but maybe outlandish in a public comment, and we’ll try to walk through that information with the Documenter and help fact-check it in real-time or fact-check when they’re doing their notes. And I understand that it’s very, very frustrating, but a lot of people really are going into it with their own perspectives and their own life experiences, and finding out how they ended up at that point to believe in a piece of information and spread it around will allow you to have more grounded conversations.

We’ve touched on a few bleak topics, but I wanted to end on a more positive note: What keeps you hopeful about the profession as disinformation continues to spread and people grow more upset with the state of things?

I kind of have two answers here. What keeps me hopeful about just the state of democracy in general, is that people are active, and surprisingly so. I can’t tell you how many people have – during the recruitment effort, people have said it was exactly what they were looking for, or people were already going to public meetings in their own time just to find out more about what’s going on and bringing that information back to their community. There are a lot of individuals from just the city of Dallas who understand the power and the importance of understanding that process and giving that information to their communities, especially if they are undervalued communities. That’s really been fulfilling. Every single time we recruit people or we have a new training, there’s always just a handful of people who are so passionate, who come with incredible life experience and are committed to this mission, not only going to these meetings, doing the assignments and making a little money, but really making an impact and understanding things better themselves, and taking that back to their neighbors.

In regards to the profession, I mentioned that there are newsrooms that seem to be trying to do things differently. I think we’ve clearly realized that, for many reasons, some of the ways we report or some of the ways our newsrooms are structured are just not sustainable, sometimes for financial reasons, but also not sustainable for attaining trust, not sustainable for providing information consistently. It’s not sustainable for providing the right context and the right framing for certain stories. Everyone doesn’t have to like us – I don’t think that’s what we’re looking for. But I think having people who understand the important work that we do and really leaning on us for that information – that has obviously been eroded. So the fact that there are newsrooms and people – and I would even say subsections within traditional newsrooms – that are trying to change our current reality – again, not only in the economic sense, but also in the community-building sense – gives me hope. When a lot of the time I grew frustrated with being in more traditional newsrooms, I’ve kind of seen a new light being in a nonprofit newsroom and having straight-up different priorities.

David Silva Ramirez is the civic editor at The Dallas Free Press. He previously covered racial equity and education at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram.

(PEN America runs a digital safety and online abuse defense program for journalists, including training for journalists and newsrooms, short videos on how to protect yourself from doxing and hacking (Digital Safety Snacks), and a comprehensive guide on navigating online abuse (Field Manual).)