Kyle Hedquist is standing at his cell window, looking through the rusty iron bars at the falling snow. It’s 4am and he’s made himself a cup of instant coffee using lukewarm water from his cell’s sink. Drinking and watching the fast falling snow coating the prison yard, he writes, “It was beautiful, and I felt privileged to be witnessing this…” As he stares, lost in memories from past snowy days with his grandfather on their family farm mingled with those from the night he committed the crime for which he is incarcerated, he hears someone behind him say, “Are you OK?” He turns and a guard shines a flashlight into his cell: examining, probing. He replies, “Oh, I’m fine” and the guard walks off. But, Hedquist writes, despite the brevity and seeming innocuousness of the encounter: “Surely I would be submitted for a urinalysis in the morning.”

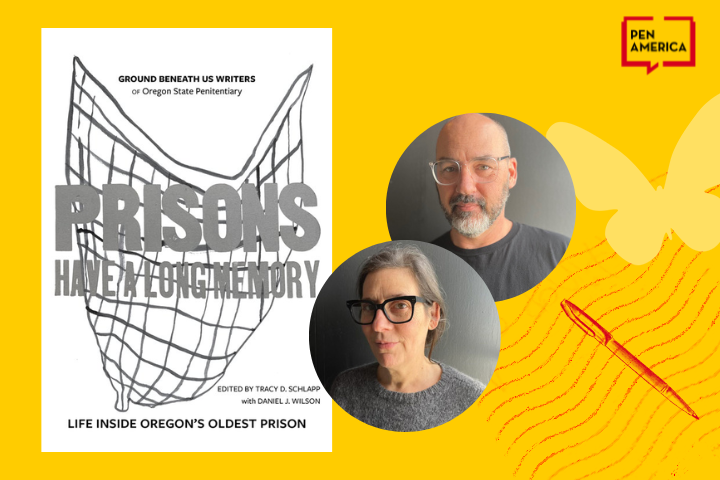

To stand and watch the snow fall when you’ve woken in the night and can’t sleep is a cause for suspicion. He will be examined for his snow gazing and coffee sipping. Suspect for finding a moment of peace in a place that denies emotional lives are foundational to human existence. While prisons may seem a complete remove from most peoples’ daily lives, this instance and many more like it in Prisons Have a Long Memory (2022), edited by Bridgework Oregon’s Tracy D. Schlapp and Danny J. Wilson, demonstrate how prisons are extreme versions of the cultural standards we all live with.

While extreme in prisons, conformity is demanded of us all at the expense of our emotional and psychological lives. It moreover denies us the right to process our lives, an increasingly traumatic experience. Despite the myriad, intersecting, and relentless distresses of contemporary life, we are obligated to eat, sleep, get up, and go to work every day. To pay our bills. To invest in a system that invests so little in us. It is a lot like prison where Nolan James Briden, in his essay “What is an Average Day?”, explains how he exits his cell in the morning and walks to a call center, built just outside the prison gates. He will sit there all day, making calls for Advice Brand. He is paid cents an hour. Briden still values his job, it seems. But, although a break from the endless hours some incarcerated people spend staring at the ceiling in their cells, such routines are a repetition that at least obscures reflection–denying space and time to meditate on the purpose and meaning of our lives.

Of course, prisons supposedly remove people who are doing harm to others: a necessary evil. The specious logic of the prison is that certain individuals are bad. And yet, as many familiar with prison stories would expect, this volume demonstrates that the “criminal” authors were first victims–sometimes of horrible abuse and systemic neglect that was culturally created. What these stories reveal is that, as a culture, we invest in punishing wrongdoing over and above supporting and caring for people who have been abandoned or abused. Sterling Cunio was given a life without possibility of parole sentence when he was sixteen years old. After twenty-seven years inside, he was granted clemency. Cunio’s essay included in the volume, “Liminal Reentry,” reflects on how there is little support for people who have suffered. Sterling recognizes this most acutely, ironically, when he is released. Although he has a group of people waiting for him at the prison gates, another person released on the same night has only one, crying woman to meet him. Cunio asks: Does she have the resources herself to support this man’s transition back into the society that condemned him? The challenges are myriad, emotional and psychological–not just logistical and practical. For example, Cunio feels hypervigilant in public, assessing the risk of entering a restaurant or scoping the grocery aisle. He has lived in a hypercompetitive environment, generated by manufacturing conditions of scarcity. He’s used to people aggressively taking things in order to merely survive because survival is not the objective for carceral systems. Again, this is something we all live with. Like Sterling, we are all vigilant because, on some level, we know scarcity could be our lot. Where is the care and support for us all? Why can’t there be an abundance of care instead of an abundance of punishment?

Many stories in Prisons Have a Long Memory are flecked with unattended loss, another aspect of life in this culture we can surely all relate to. A guard comes by and tells someone their father or mother has died. They still have to rise in the morning and throughout the day to be counted by officers. It is a child’s birthday and their father or uncle is unable to celebrate with them or give them a present. They still have to do their assigned tasks, be at their assigned places. When we experience loss, we still have to go to work or school. Like the authors featured in this collection, the feeling of dissonance we experience–that our worlds have forever changed and yet is of no consequence to others–is alienating.

There is a lot to learn about life inside prisons from Prisons Have a Long Memory. But although it is a collection of writings from prison, the stories, poems, and essays reveal the commonality of living inside and living outside. Reading this collection as a reflection of our culture back on us, in the starkest of terms, suggests creativity and care might be the antidote to so much of what plagues us. Prisons Have a Long Memory is a pharmakon–offering both illness and its cure.

Moira Marquis is the senior manager of The Freewrite Project for PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program. She has worked with Asheville Prison Books and co-founded Saxapahaw Prison Books. She is co-editor of the forthcoming volume, Books Through Bars: Stories from the Prison Books Movement (University of Georgia Press, 2024).