Bo Hee Moon | The PEN Ten Interview

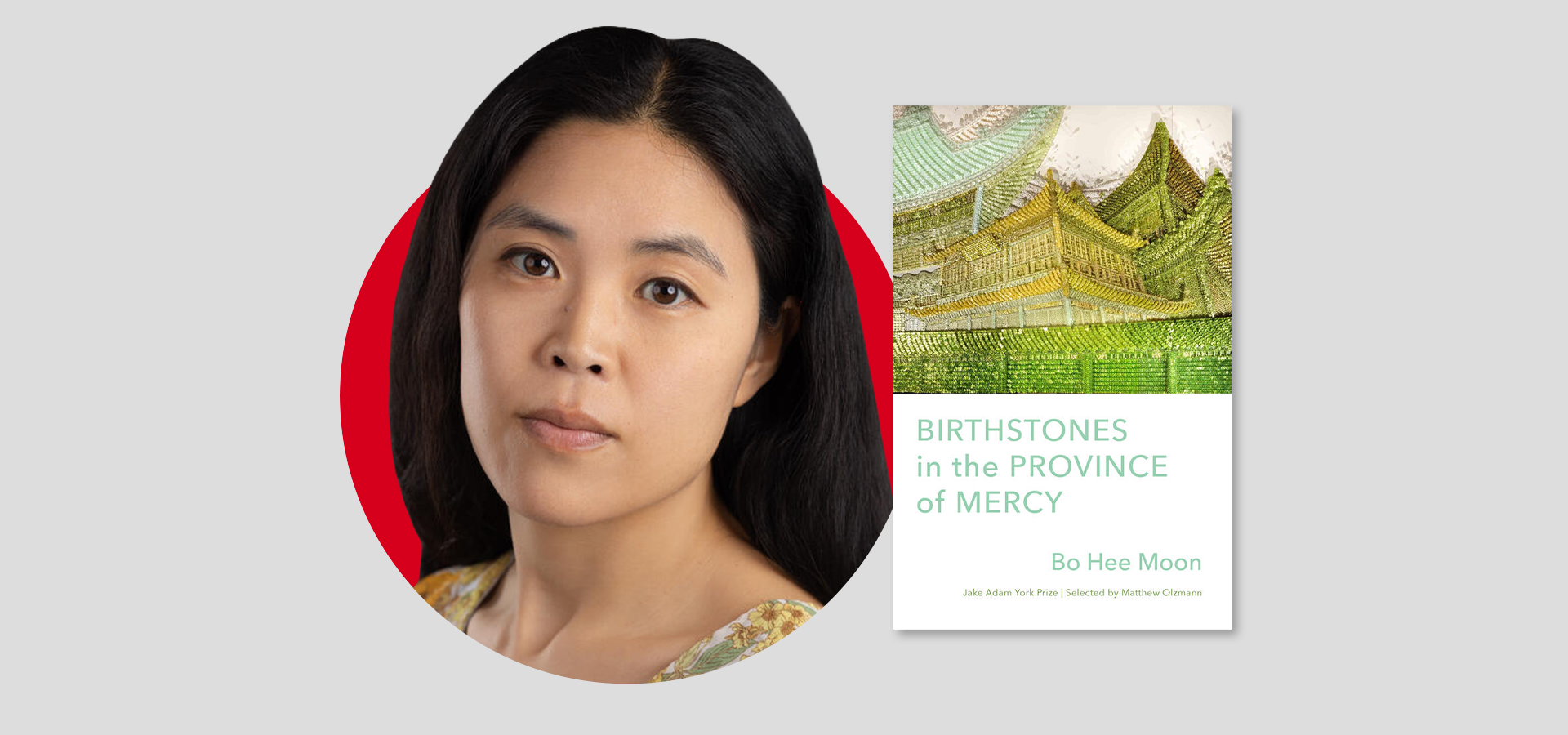

In poet Bo Hee Moon’s newest collection, Birthstones in the Province of Mercy (Milkweed Editions, 2026), an adopted daughter and her birth mother reunite across time, cultures, and fate. Moon captures the complex emotions she feels about her identity as a South Korean adoptee, using verse to process her grief, trauma, and love. Winner of the Jake Adam York Prize, this collection is a transparent and masterful wielding of raw emotion.

In this PEN Ten interview, Michelle Danglade, communications intern, speaks with Moon about her writing process, the value of memory, and the power of hope. They discuss Moon’s journey from America back to South Korea and the strength that can be found through connection (Bookshop; Barnes & Nobles).

Birthstones in the Province of Mercy tells not only the story of your adoption but also the imagined reality of what your life would’ve been had you grown up with your birth mother. After regaining your maternal connection through research and travel, why did you choose to blend imagination into the known facts of your adoption story?

The power of the speculative allowed me to reimagine possibilities. Opening a space of potentials, the imaginary cast the facts of my adoption story in a new light and illuminated the healing forces within a poem. In this space, I found that I could access my desires and longing. Within the absence, my yearning became audible through language. Blending imagination into the known facts often created the energy and the music of a poem.

In Birthstones in the Province of Mercy there are many references to Korean culture, particularly Korean food and language. Why do you think these cultural artifacts such as food and language are so important for building communal, especially familial, connections?

I often think about how my birth mother thought, spoke, and most likely dreamt in Korean. I imagine what she ate and if she loves salt like I do. I feel an absence within me regarding the Korean language and yearn to connect with it. Food and language have the ability to bring intense comfort and connection. There can be a communal element to sharing Korean food. In an article in The New York Times, Eric Kim explores kimjang as “living heritage” and states “kimchi is the national dish of South Korea and traditionally prepared at a kimjang, the communal act of making and sharing kimchi. Over the course of multiple days each November, neighbors and family members gather to preserve pounds and pounds of butter-yellow napa cabbage by salting them and then mixing and packing them with sauce.” This is one example of a tradition rooted in nurturing a sense of connection. I was separated from my birth country, my birth country’s language, and my birth mother. Due to my past history, I am drawn to traditions and rituals that nourish familial and communal connections. Food and language often remind me of my connection to my body, my spirit, and my community, which sustain my sense of hope. I love sharing meals and the banchan at the center of the table.

In this collection, we see many references to astrology and natural phenomena, particularly when it comes to water. For example, in “Halmeoni,” you describe the act of drinking from a lake instead of a river or stream, and in “Letters to Omma-Escape,” you mentioned that making it to the sea is a recurring dream of yours. What does water symbolize in your poetry?

Water means many things to me in my poetry. I often think about the Pacific Ocean connecting Korea and America. The ocean is where I feel most alive and peaceful. I used to have a recurring dream where I would try to get to the ocean. It could represent a longing to connect with my birth mother as well as my own essence. Due to my past, there were many layers covering my essence — things that were not me but seemingly necessary for survival. Over time, poetry helped me to release what was not mine.

Now, there are moments when I go to the ocean and imagine my birth mother’s presence. Last month, on a cold day, I saw a girl and a woman together, most likely a daughter and mother. The sun set — a blaze across a sea. I stood near the sea grass and beach evening primrose. I listened to the quiet as if I could hear my birth mother’s voice.

I am drawn to traditions and rituals that nourish familial and communal connections. Food and language often remind me of my connection to my body, my spirit, and my community, which sustain my sense of hope.

The obtaining of freedom is another prevalent theme throughout this collection. In “Escape,” again, you mentioned that you have gotten to a point where you have learned how to fly because you took away what was blocking you from escaping. What does freedom look like to you? How does writing help you achieve it?

Feeling safe is an essential element of freedom. From this safety, the voice and creativity emerge. Being in my body enhances my sense of freedom. Writing connects me to my voice. Each poem is revealing. I may discover a music, a tension, an intense emotion, a desire, a longing. Writing a poem often changes me. Writing this collection helped me to articulate my yearning for my roots. This past summer, I went on an adoptees’ trip to Korea and visited my birthplace. I would like to imagine a world where we can all be safe, and in this way, we potentially can have the chance to be free.

I am thrilled and thankful that Ran Hwang’s artwork “First Wind” appears on the cover, and Mary Austin Speaker and the team at Milkweed are absolutely fantastic. When I first saw Ran Hwang’s artwork, I felt immediately moved and more attuned to freedom. Freedom is also the space to create, expand the mind, feel — it is the right to exist.

Many poems in this collection explore the struggles you faced growing up in an abusive household and having very little knowledge of your birth parents. How has writing this collection helped you with processing your experiences?

It was often difficult writing about my past. The process of writing each poem supported me in discovering potential beauty. When I wrote “Letters to Omma—Reunion,” revisiting past memories was painful. I wrote the poem gradually. By slowly writing the poem, I became more aware of the beauty around me: “The bitter red / fruit attracts / wood thrushes / where I live now— / a sudden spring / pea, eastern / pink light, / budding gently / before me.” After reflecting on experiences from my past, these gentle moments allowed for renewal. Writing the collection provided insight into how to leave an abusive household and how to find hope in my present experience.

Similarly, memory is a topic throughout the collection — how we form our memories and how we access them. What role does writing play in navigating memory for you?

Recently, I’ve been reflecting on how a poem begins. I sometimes begin with a sound, an image, or a memory. When I am exploring a memory, I am often making sense of the meaning held within the memory. The memory may be a catalyst for a poem that evokes images and sound. Writing encourages me to stay with a memory and uncover why I am drawn back into memory.

Writing connects me to my voice. Each poem is revealing. I may discover a music, a tension, an intense emotion, a desire, a longing. Writing a poem often changes me. Writing this collection helped me to articulate my yearning for my roots.

In an interview with Cream City Review, you talked about your journey connecting with your past and how, in your twenties, you actually visited your adoption agency to learn more about your birth and mother. What is a piece of information that you learned during this journey about your past and culture that you find sticks with you the most or that has influenced your writing the most?

I was born in a village, taken to Holt, and then went to a foster family before coming to America. When I visited Korea in my twenties, I went to Holt. I met with a representative of Holt, reviewed my adoption records, and asked to see where I was taken when I was a newborn — on another floor of the building, there was a room where the babies were kept. I could imagine myself as a newborn in this room. It struck me how small I must have been. I felt fortunate that I survived.

You have also said in your interview that you always want to break down a poem into its rawest form and leave it unburdened by “embellishment.” In Birthstones in the Province of Mercy, many of the poems are couplets imbued with strong emotions such as pain, nostalgia, grief, love, and resilience. How do you know that you have reached a poem’s purest form without any excess?

There are some poems where I have written 50 to 100 drafts or more, making small changes in each version. There are times when I need to take some space or time before returning to the poem. I sometimes print out a poem and continue exploring the poem by making handwritten notes. I often have a feeling when the poem is complete.

What impact do you see adoptee narratives making on society? What difference do you hope your collection will make?

Adoptee narratives are making a profound impact on society. I am greatly inspired by adoptee poets and writers. Lee Herrick, Poet Laureate of the State of California, is a brilliant force in the literary community. His book In Praise of Late Wonder, released by Gunpowder Press, is extremely moving. In his poem “How Music Stays in the Body,” the speaker addresses his birth mother: “I can’t remember your face, the shape or story, / or how you held me the day I was born, so / I wrote one thousand poems to survive.” This lyric power creates beauty in the world. Additionally, Jennifer Kwon Dobbs 허수진 and Lee Herrick co-edited Afterlives: An AGNI Portfolio of Asian Adoptee Diaspora Writing.

There are many amazing people uplifting and supporting the adoptee community. Susan Ito (Co-Director), Alice Stephens (Co-Founder & Co-Director), Marci Calabretta Cancio-Bello (Co-Founder, Board Member), and their wonderful team host the Adoptee Literary Festival, which fosters community and honors adoptees’ voices. Adoptee narratives are raising awareness about important topics, including the Korean adoptee diaspora, identity, and belonging. I would love for my collection to bring readers a sense of renewal, hope, and connection.

It is important for adoptees’ voices to be honored, our questions to be addressed, and our histories to be reclaimed. Support and love from our communities are vitally nourishing.

South Korea recently joined the Hague Adoption Convention, which established international adoption standards 30 years after it was ratified, and President Lee Jae-myung has apologized for the corruption that was involved in the country’s previous foreign adoption programs and failure to safeguard adoptees’ human rights. Did you do any research into the history of adoption when writing this collection? How does the shifting global context change or not change what you hope readers will take away from your poems?

I read articles such as Eleana Kim’s “The Origins of Korean Adoption: Cold War Geopolitics and Intimate Diplomacy” and considered the historical context surrounding adoption as well as how adopting from Korea was portrayed in the media. Kim concludes, “In this historical account of the early period of Korean adoption I have suggested the significant ways in which sentimentalized constructions of children neutralized highly charged political contexts, but also how the movements of actual children mediated intimate relations between states and their different biopolitical projects during the Cold War.” I value research that sheds light on the complexities within transnational adoption.

The shifting global context change impacts many readers. Some readers may be searching for their identities, histories, and truths. Unfortunately, there have been falsifications, obscured documents, and missing records (See the NPR article “South Korea halted its adoption fraud investigation. Adoptees still demand the truth”). Many adoptees are navigating change while looking for deeply personal information and connections. It is important for adoptees’ voices to be honored, our questions to be addressed, and our histories to be reclaimed. Support and love from our communities are vitally nourishing. I hope that readers feel a sense of connection and groundedness within themselves during these times of change, questions, and heartfelt searching.

Bo Hee Moon is a South Korean adoptee. Born in South Korea, she was adopted at three-months-old. Her poems have appeared in Cha, CutBank, diode, Radar, Redivider, The Offing, Zone 3, and others. Omma, Sea of Joy and Other Astrological Signs, published by Tinderbox Editions, is her debut collection of poems. She previously published under a different name.