Russian forces kidnapped Volodymyr Vakulenko—twice. After the first abduction, the children’s author buried his diary under a cherry tree in his home garden in Kapytolivka, a village in Ukraine’s Kharkiv Oblast. He told his father to “give it to our people when they come.” After the second abduction, on March 24, 2022, he was shoved into a bus and never seen alive again. Recovering his diary months later, writer Victoria Amelina carried Vakulenko’s story for the rest of her life.

Before the war, Vakulenko was known for the gentle, warm images captured in his children’s books: colorful inflatable balloons, plums, apples, and the song of a finch. But then came Russia’s full-scale invasion and his writing became filled with pain and the realities of war: “During the first days of occupation, I gave up a little, then due to my half-starved state — totally.”

Three years after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Vakulenko’s writings ensure that his story and the voices of Ukrainian writers live on.

Vakulenko was found dead several months after his abduction, his body shot with bullet holes in a mass grave marked “319” discovered in the de-occupation of Izyum.

After his death, writer Amelina recovered Vakulenko’s buried diary. She sent photos of each page to Tetyana Teren, then executive director of PEN Ukraine, and the Kharkiv Literary Museum. Amelina, a novelist, was volunteering with the Kyiv-based organization Truth Hounds to document war crimes since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion. Her diligent work became the basis of Vakulenko’s posthumous book I Am Transforming… A Diary of Occupation, featuring his notes on occupation, selected poetry, and works by fellow Ukrainian writers. “As long as a writer is read, he’s alive,” Amelina wrote in the book’s foreword.

Just days after presenting Vakulenko’s book in Kyiv, Amelina died on July 1, 2023, a week after sustaining injuries in a Russian missile attack on a restaurant in Kramatorsk. Before her death, Amelina had been working on a manuscript for her first nonfiction book, chronicling stories from the ground. Her posthumous book Looking at Women Looking at War was published last week. “The quest for justice,” she writes, “has turned me from a novelist and mother into a war crimes researcher.”

Amelina and Vakulenko are among the more than 100 Ukrainian writers, poets, publishers, and translators who have died since February 2022. PEN Ukraine and partners have documented the stories of Ukrainian cultural figures killed by Russia to preserve their memories and advocate for accountability. Their deaths are an incalculable loss for Ukrainian culture and part of an assault on the cultural community—a clear target of Russia’s war. These aims have fueled the bombings of more than 1,000 Ukrainian cultural institutions, including the Khanenko Museum, the Mariupol theater, and the Kyiv Picture Gallery National Museum.

In Crimea, illegally occupied by Russia since 2014, Russia is attempting to erase the Tatars’ culture and language while jailing writers, journalists, and activists.

Crimean-based Ukrainian journalist and PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award honoree Vladyslav Yesypenko has been held in Russian custody for nearly four years. Yesypenko’s journalism focused on life under Russian occupation; days before his arrest, he was collecting footage for a video about how Crimean residents’ lives had changed in the past seven years. He was arrested after reporting on an event honoring Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko in March 2021.

PEN America calls for Yesypenko’s immediate and unconditional release and for the Russian government to be held accountable for free expression violations and war crimes, including the destruction of cultural sites and the killings of writers.

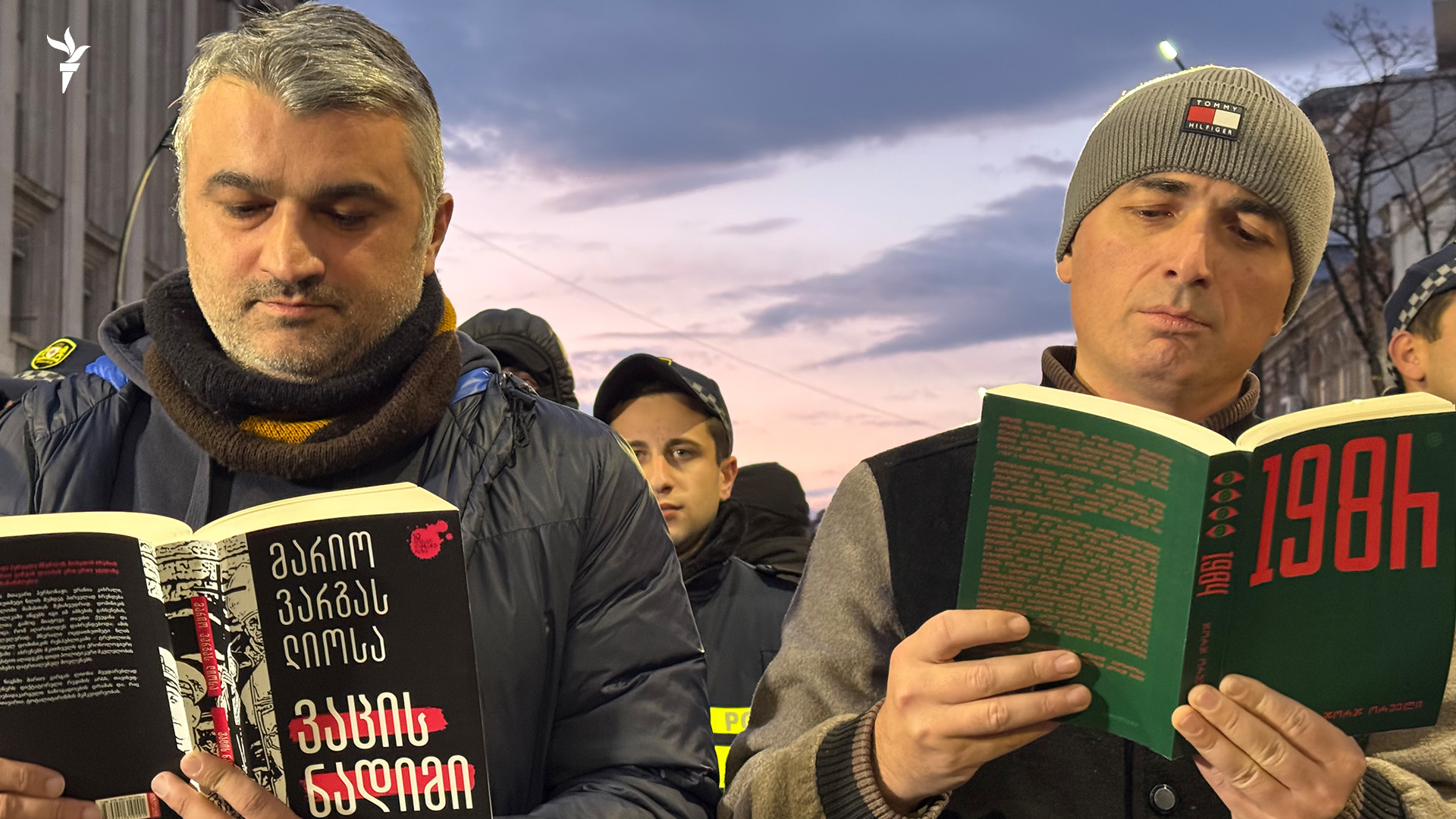

In the foreword to Vakulenko’s diary, Amelina warns: “My biggest fear is coming true… Like in the 1930s, Ukrainian artists are killed, their manuscripts vanish and memories about them fade.” But through the work of writers, translators, and readers, Vakulenko and Amelina’s words are immortalized in pages, public readings, and kids’ storytimes around the world. With this unbearable yet essential task, the editors of Amelina’s book write, “Life has taught us that there is only one way to deal with the pain: to continue the work of the people we love.”