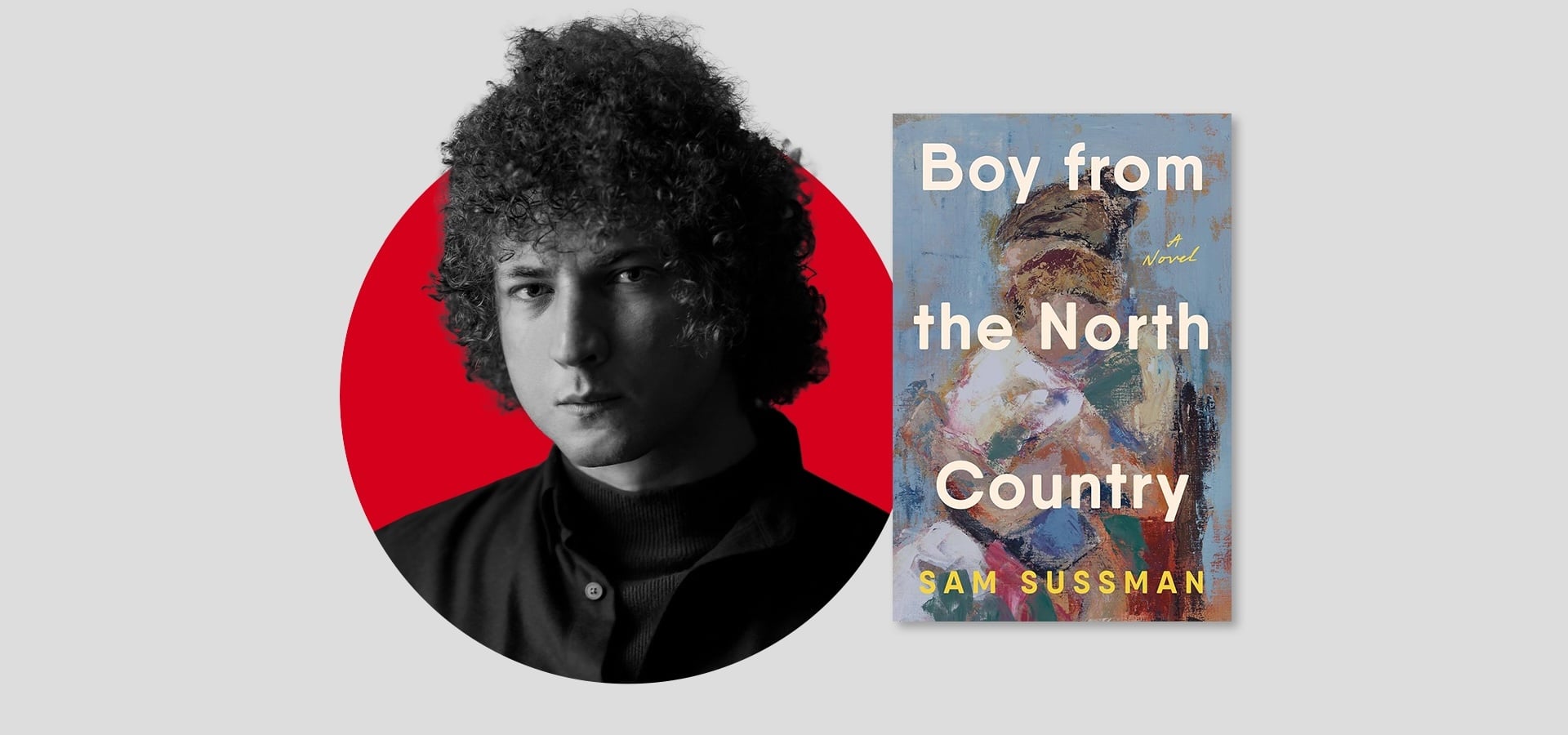

Sam Sussman | The PEN Ten Interview

Essayist Sam Sussman turns to fiction in his debut novel Boy From the North Country, which was inspired by his own life story. Protagonist Evan grew up not knowing who his father was. Living a life abroad, he is suddenly called home by his mother who had been keeping secrets about not only her past relationship but her present health.

In conversation with PEN America’s Literary Awards Intern Frances Michaels for this week’s PEN Ten, Sussman reflects on finding stability in one’s ever-evolving identity, why certain Bob Dylan songs resonated with him, and the reasons behind his narrative decisions in Boy From the North Country (Penguin Press, 2025). (Bookshop; Barnes & Noble)

Join PEN America and 92NY for a conversation with Sam Sussman and Ayad Akhtar on Sept. 19.

Boy from the North Country was inspired by your own uncertain celebrity paternity. You first explored this in your essay “The Silent Type: On (Possibly) Being Bob Dylan’s Son.” What inspired you to expand this essay into a novel, and how did that process reveal what you describe as the “infinite gifts of being [your] mother’s son”?

My mother and Dylan had a romantic relationship. She almost never spoke to me about this. Growing up, I was often told by strangers that I resembled him. That raised certain questions. Dylan was an artistic idol for me. I was a misfit in a small town and I wanted to get on a freight train to New York like he’d claimed to have done. When I was 15, my mother confirmed that she and Dylan had once had a relationship, and that she had been involved with him the year before I was born. The idea that he could be my father—

Four years ago, after my mother’s death, I wrote an essay about my journey to understanding that it matters more to me that I am my mother’s son than that I may be Dylan’s. Most people told me to expand that essay into a memoir. It’s conventional advice to a young writer: Memoir sells more than fiction, and it’s easier to find a publisher. But I knew it was the wrong artistic choice for me.

Samuel Beckett has a great line: “You have to find the form that fits the mess.” By the end of my essay, I write what I have felt for years: It doesn’t matter whether he’s my father. I don’t know him. My mother has given me everything I value most in myself. She raised me. She loved me. She gave me my self.

What’s the form that fits that mess? What form tells us that facticity is not the ultimate truth in our lives? The novel by its nature neither confirms nor denies facticity, but rather renders truth and meaning through memory, observation, emotion. I had always hoped to write a purposeful novel, and, after my mother’s death, I knew that it was time to begin.

The title Boy from the North Country plays on Bob Dylan’s song “Girl from the North Country,” which tells the story of a lost love. In your novel, Dylan even changes the lyrics to reference a boy. Why did this particular song resonate with you as the title?

You know a boy from the north country when you meet one. Outsiders, people from small towns, the provinces, who arrive in the city in search of a more expressive self. There are many boys from the north country in this novel. Dylan, of course. Norman Raeben, the painter. Marc Chagall, who first won acclaim in Paris by painting the shtetl he had been desperate to leave behind. Joseph, from Genesis. My mother. I’m a boy from the north country, of course. The north country is where Basho was traveling, the narrow road to the deep north. It’s Nick Drake’s northern sky. It’s your origin and your destination.

The novel by its nature neither confirms nor denies facticity, but rather renders truth and meaning through memory, observation, emotion. I had always hoped to write a purposeful novel, and, after my mother’s death, I knew that it was time to begin.

One of Dylan’s most popular songs, “Tangled Up in Blue,” contains a line you connect to your mother. In the novel, as he plays this song for June, he says, “No poem is ever finished because it is a way of life, there is never anything on the other side of struggle but more struggle.” Do you find this to be true in your own writing? How do you decide when a piece is truly ‘finished?’

Dylan and my mother were romantically involved the year he wrote Blood on the Tracks. One night, at her place, she lit a burner on the stove and offered him a pipe. Then she read him Petrarch and he was taken by the words. There’s always been speculation about which poet he’s referring to in that line, “Then she opened up a book of poems / And handed it to me / Written by an Italian poet / From the thirteenth century.” Dylan once told a journalist he meant Plutarch, the Roman writer from the first century AD. That’s Dylan for you. As for poems, I don’t think they’re ever finished. Neither are novels, for that matter.

As Evan watches Bob Dylan perform with his mother, he sees Dylan shift through the many versions of himself until, “fifty-seven years later, he was still becoming himself.” How does this moment mirror Evan’s own journey of self-discovery, and how does he find stability when identity is always evolving?

Evan has always wanted to leave home and find himself as an artist. He’s left his origins far behind, lived abroad his entire adult life, had a formative education, spent years writing. But nothing he’s written is worthwhile. There’s a novel inside him and he can’t write it. Evan is slowly realizing that what he’s been missing as an artist is his mother’s wisdom. He’s been writing from bitterness, not love. Resentment rather than redemption. That’s why nothing he writes is worthy. He has to journey toward the realization he makes late in the book: “It was time to begin the more difficult and worthy work of writing a book drawn from my mother’s wisdom.” In this regard, Evan shares something with the narrator of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, a writer who is also learning to find the novel within him, which becomes, by the end, the novel we are reading.

In many cases, women’s stories of abuse, sexual assault, and rape are pushed beneath the surface, buried in denial, silence, or a lack of recognition. In the novel, June discusses her experiences with Evan. Why is it important for stories of trauma to be told, especially to young men?

Let’s be clear: Silence enables sexual violence. The shame that women (and men) are made to feel in speaking about their subjection to sexual violence is part of that violence itself. My mother wanted to break that cycle. She spoke to me about her experiences. She used to say, “We are here to take the pieces of the universe we have been given, burnish them with love, and return them in better condition than we received.” For her, that meant drawing on her experience of sexual and domestic violence to help other women who had been subjected to similar trauma. I wanted to give voice to that part of her life in Boy From the North Country. It was important to me to share with others how she modeled what it means for a mother to speak candidly to her son about sexual violence.

Truth is more than the facts and memories of our lives; truth is the story we choose to tell from those facts and memories.

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone appears as a recurring reference throughout the novel as Evan reads the story to June. Notably, Evan reflects on Dumbledore’s reminder that we must not dwell on dreams but live our own lives. Why did you choose this particular symbolism and that story?

I’m the Harry Potter generation. I waited all year for the summer day when that year’s book would arrive in our mailbox. My mother and I spent so much time speculating about what was going to happen in the next book! Once the book arrived, we spent treasured summer afternoons with her reading aloud to me in our hammock. In my twenties, when she was going through chemotherapy, I read Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone aloud to her. Often, when she was in pain at night, the story helped her ease into sleep. I felt in those moments the healing power of literature. I also began to see Harry Potter through my mother’s eyes. For me, as a child, it had always been the story of a boy who becomes a wizard. For my mother, it had been the story of a mother’s love protecting her son. Love, of course, is the true magic of those books.

A constant theme throughout the novel is June’s unwavering faith in love, whether romantic or familial. Was this belief something your mother instilled in you, and how did this faith influence the way you shaped June’s character?

My mother used to say, “Nothing is holier than love.” I wanted the reader to meet the woman I knew, who believed in love above all else.

At the conclusion of Boy from the North Country, Evan’s relationship with June becomes more important than the question of whether Bob Dylan is his father when he learns she’s been hiding the progression of her illness. What does this moment reveal about the role of “truth” in our lives?

Truth is more than the facts and memories of our lives; truth is the story we choose to tell from those facts and memories. Evan knows that he is going to be alone after his mother’s death. He will have to decide for himself who he wants to be and what truths he will live by. He chooses to define himself as his mother’s son.

Music is such an intimate art form. You put on a song and your mood is transformed within moments. I think music must be the most popular thing on the planet. Or a close second, behind ice cream.

Evan recalls his mother saying, “nobody ever spoke to [Dylan] but rather to his songs, to the memory and feeling that his music evoked within people he did not know.” Do you think this kind of connection to music still exists today?

Yes, she says as well that every room Dylan walks into is a story someone else has already written. Music is such an intimate art form. You put on a song and your mood is transformed within moments. I think music must be the most popular thing on the planet. Or a close second, behind ice cream.

The ending of the novel remains unresolved when it comes to Bob Dylan, but ultimately, the story was never about him; it was about June. If she could tell us directly, what do you think your mother would want readers to understand about her story?

What matters in life is whether people are there for you. When you suffer, when you thrive, who is there to love you as you deserve to be loved?

Sam Sussman grew up in the Hudson Valley. He graduated with a BA from Swarthmore College and an MPhil from the University of Oxford and has lived in Berlin and Jerusalem. His writing has been recognized by BAFTA and published in Harper’s Magazine. Sam has taught writing seminars in India, Chile, and England and participated in the PEN World Voices Festival of International Literature. He lives in the Yorkville neighborhood of Manhattan and his native Hudson Valley.