For centuries, children have studied the art and history of the ancient world and the European Renaissance to learn the underpinnings of Western civilization. But in a growing number of this country’s school districts, students may be stuck believing Michelangelo, Leonardo, Donatello and Raphael are just the names of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, because some books that describe these masters – along with a host of other artists and artistic movements, including works about ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome – have been removed from the shelves in their schools.

“It’s difficult to study art history without a bit of nudity,” says Kasey Meehan, director of PEN America’s Freedom to Read program.

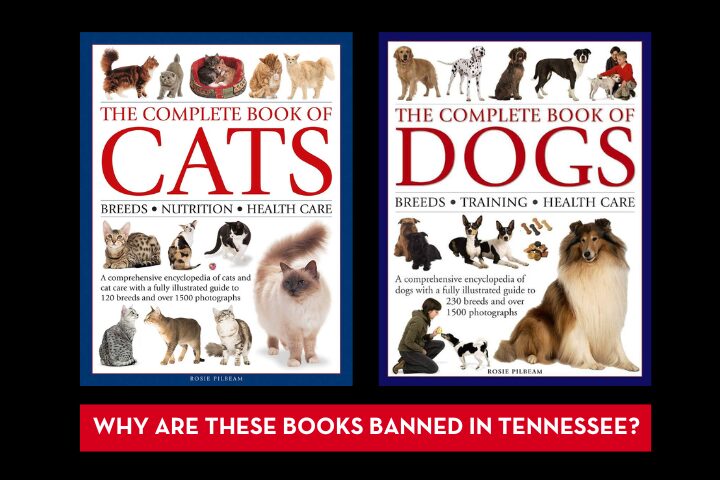

However, over the last several years, efforts to remove “sexually explicit materials” or books with “sex content” has chilled access to art in schools. More recently, a state law in Tennessee puts an explicit prohibition on naked images. The law, which took effect in July 2024, now requires schools to remove books that contain nudity.

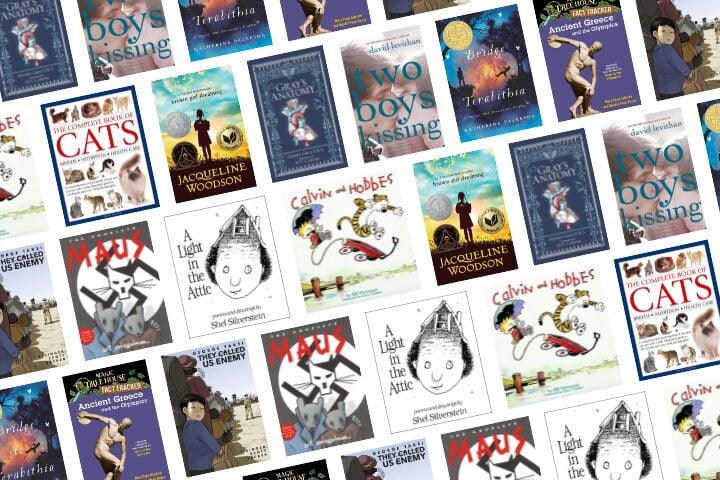

The bans that followed these statutes encompass dozens of biographies of artists, along with scores of texts written for school kids with titles like Ancient Greek Art and Architecture and The Italian Renaissance, and many with broader themes like The History of Archaeology and The Story of Sculpture – all pulled off the shelves in Oak Ridge School District in Tennessee. In Monroe County, Tennessee, books like Art and Culture of the Renaissance World, and Life During the Great Civilizations, were removed. In Manatee County, Florida, they removed Michelangelo’s David. In Tallahassee, a principal was forced to resign for not warning parents that an image of that statue would be presented in a lesson to sixth graders. Nude statues have also been cited in banning a graphic adaptation of Anne Frank’s Diary.

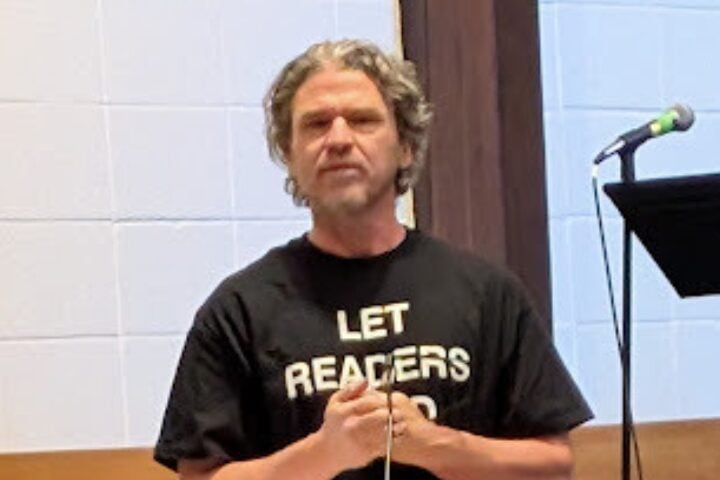

Don Nardo, a prolific writer of art and history books for educational publishers with almost 600 titles to his credit over 35 years, had at least 11 books banned in various districts in Tennessee alone, most of them about ancient civilizations.

“It’s mostly just the last three or four or five years that I’ve been hearing about books being banned,” Nardo said in an interview with PEN America. “It just seems such a shame. How is it hurting someone, for goodness’s sake? Everybody sees themselves naked in the mirror.”

“This censorial trend reflects both poorly written laws and overcompliant school districts,” said Meehan. Indeed, many of the books were removed preemptively, not in response to any parental complaints.

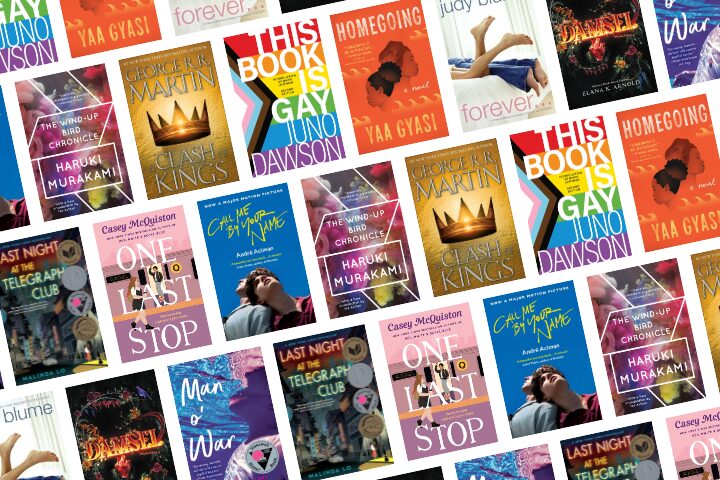

Art and history books are generally not the primary targets with most efforts to ban books. Books about race, racism and LGBTQ identities are disproportionately included in the bans documented by PEN America, which include more than 10,000 instances in the last school year and more than 16,000 since 2021.

In the guise of protecting students from so-called corrupting material, for example, Tennessee banned books that depict humans unclothed – even if the photos in question are of 3,000-year old statues.

The language of the law appears to catalyze book banning, prohibiting: “material that in whole or in part contains nudity, or descriptions of depictions of sexual excitement, sexual conduct, excess violence or sadomasochistic abuse” as “not appropriate for the age or maturity level of a student in any of the grades kindergarten through twelve.”

And the result of the law is sweeping, said Xan Lasko, the Intellectual Freedom Chair of the Tennessee School Library Association, which is a 123-year-old membership association of library staff.

“There was no difference made in the law between photos of statues and naked people,” explained Lasko, a retired librarian who worked in Rutherford County, Tennessee.

Lasko noted that a 1973 Supreme Court decision established the three-pronged Miller test to determine if material is obscene, and therefore not protected by the First Amendment. The factors include that the average person would consider that the material, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest; that it depicts sexual conduct in a patently offensive manner, and that the work lacks serious literary value. “We don’t have any of that,” she said, adding that it’s “inherently unconstitutional” to take away books because some people don’t like what they say or how they say it.

Some districts in Tennessee went for broad sweeps and removed every book that contained any naked image – including a raft of health and science books like, The Body: A Guide for Occupants, banned in Oak Ridge schools.

One big concern is that districts typically have a policy to review books that parents challenge, but in many cases, these books were removed without anyone calling them into question, Lasko said..

“Many times, that challenge procedure is not followed, they just decide on a list of books,” Lasko said. “I’ve been keeping a spreadsheet,” she continued, noting that while some of the books banned in the state were the subjects of parental complaints, many were not. In some cases, she said, school officials followed the leads of other districts and removed all of the titles taken down in other communities.

And there’s little opportunity to appeal these decisions, she added.

Nardo hopes the time will come when many school districts and states change the policies leading to book bans.

“I don’t quite get what they think that this banning will do,” Nardo added. “I just think to myself, if they want to ban this and they ban that, what’s left? What do they want people to read?

“It’s almost like they’re not thinking,” he concluded. “I can’t say I understand that mindset at all.”