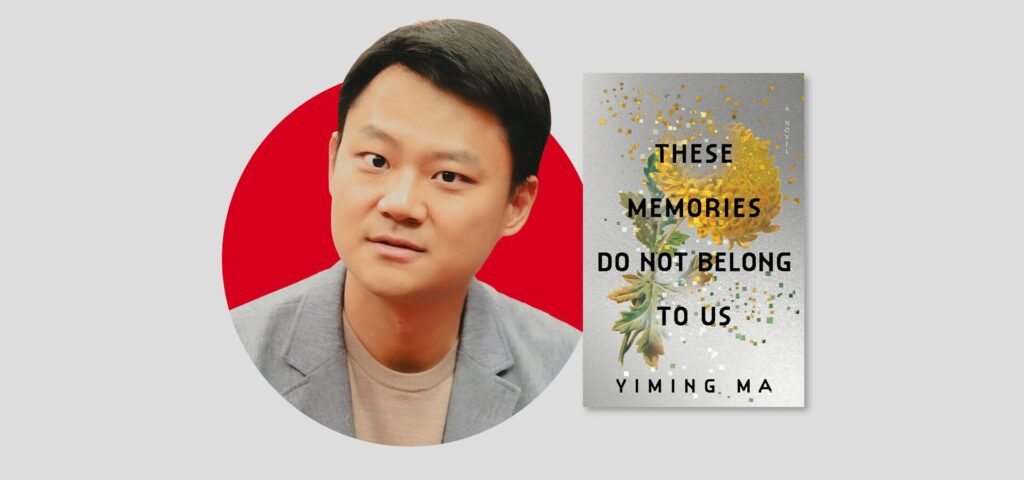

Yiming Ma | The PEN Ten Interview

Set in a world where memories are bought and sold and the Qin empire has taken over, These Memories Do Not Belong to Us follows an unnamed narrator who inherits a collection of banned memories from his deceased mother. What emerges in the debut novel by writer Yiming Ma (Mariner Books, 2025) is both gripping speculative fiction and a profound meditation on resistance, identity, and the power of collective memory in an age of increasing surveillance and control.

In conversation with Digital Safety & Free Expression Program Coordinator Amanda Wells, Ma discusses writing as resistance, the power of stories and memories, and the ambiguity of censorship. (Bookshop; Barnes & Noble)

These Memories Do Not Belong to Us takes place across the Qin dynasty, which is hinted to be former China and the United States. How did your experience living in these two countries contribute to the novel’s conception?

These Memories Do Not Belong to Us is the culmination of my life experiences. I don’t think I could have written this book had I not spent my childhood between Shanghai, New York and Toronto. However, equally important, the 11 illicit memories which comprise the majority of the novel are often drawn from my non-literary career, which brought me beyond those countries listed.

For instance, “Chankonabe,” the sumo wrestler story, was inspired by my internship at a sake company in Tokyo. “I Had Too Much to Dream” was influenced by conversations I had with social activists, while my time working in affordable education in Africa helped shape Promised Land, the story of an immigrant who must run a virtual marathon through a desert for a standardized test evolved from the Chinese Gaokao.

My childhood migrating between the East and West gave me the fascinating perspective of having lived as a member of the racial majority while in Shanghai, and then as a person of color in New York and Toronto. This inspired the worldbuilding decision to use the speculative element of the Mindbank memory sharing technology to (1) explain how the Qin empire became the sole global superpower and (2) recontextualize the stories of Asian protagonists to be read through the lens of the majority, rather than as a minority group in relation to whiteness.

After his mother passes, the unnamed narrator finds himself the unwilling keeper of a collection of banned memories. Rather than turning the memories in to the government Censors, he chooses to write and share them with others. What does this say about writing as an act of resistance?

I believe that stories matter. I believe that collective memory matters, that a shared narrative is necessary in order for people to unite and resist when called for. The truth is that marginalized communities such as Indigenous peoples have long had to preserve stories that were intentionally erased in the official archives. It’s the same reason why dictators ban books and censor discussions of genocides.

In this world where communication is done primarily through government controlled Mindbank technology, physical writing takes on particular value because it cannot be as easily interfered with. What is the value of traditional forms of writing in a world where technology is otherwise our predominant form of communication?

A handwritten letter may be one of the most touching gifts one can receive these days. Recently I even commissioned a chop seal from Hong Kong to stamp my Chinese name while I go on my first book tour.

That may not be the answer you were seeking, but I truly feel at a loss for words when thinking about calligraphy and so many arts that may well disappear in the coming years, especially as new technologies are being rapidly adopted and few continue to write by hand.

I believe that stories matter. I believe that collective memory matters, that a shared narrative is necessary in order for people to unite and resist when called for.

This is a constellation novel, and you call out the order of the stories in both the prelude and conclusion; urging readers to read them in their own order rather than as they are written. Why did you do this—and how did you choose the order of the stories?

Voice is a craft element central to my reading experience, so I spent a long time listening to the varying rhythms of the Memory Epics to determine the order. Ultimately I opened the novel with “Patience and Virtue” and “Chess and America” in order to ground the reader in a reality that had only recently changed and allow them to more deliberately explore the physical and emotional ramifications of a world that has fallen under the control of the Qin empire.The more speculative stories tend to appear later in the book, ending with “Fantasia.”

That being said, I relinquished my control of the order because I truly believe that such power was artificial to begin with. By surrendering this authority, I felt almost as if I were reclaiming my power. I wanted readers to resist against the order I set out, and I am curious how many will choose to do so.

What is it like to publish this book, which details the intertanglement of technology, censorship, and governmental control, in a moment where those ties are growing even tighter across the world?

I’m a first-generation immigrant from China. My parents grew up during the Cultural Revolution, when it was extremely dangerous to speak up. When I landed in the West, I was told by my parents to accept racism, to understand that this was not our country; that it was up to us to adapt and succeed regardless of any obstacles. I think that contributed to my decision to pursue a business and tech career and attend Stanford for my MBA before I truly dared to explore writing.

The emotional arc of the central narrator, as he debates what to do with his mother’s memories, mirrors my own journey in writing these stories – that tension between survival and resistance. Ultimately, given all the horrors happening in the world, I felt that I had to release these memories.

One of the memories, titled “After the Bloom,” follows a prospective author trying to write a novel before memory scripting makes traditional writing redundant. This echoes concerns that many authors have about what new technological developments, like AI and social media, might mean for the value of writing. As a debut author yourself, did you feel this pressure?

I began this book in the early days of the pandemic. I couldn’t have foreseen that by the time my novel was published, ChatGPT would soon have more than eight hundred million weekly active users, not to mention all the other AI models and technologies being developed. Even before this age of AI, literary fiction as a genre has been losing in the attention wars to newer media (i.e. Netflix, TikTok.) I did feel the pressure to publish These Memories Do Not Belong to Us, but not because I was afraid that books would imminently disappear. Rather, I hoped that its themes of collective memory, survival and resistance would provide some solace to readers during these tumultuous times.

I think the characters in my novel are all trying to survive and make the best of their situations, irrespective of whether they may be reinforcing the government’s power.

Because you are dealing with second-hand memories throughout your novel, you are tasked with figuring out how memories might be experienced when they are broadcast to very different people, including our protagonist. Was this challenging? How did it influence your prose?

I think what gave me permission to imagine these second-hand memories via such different forms and literary styles is my deep appreciation for the fact that people experience memories in vastly different ways.

My wife is a memory researcher at a major university and through conversations with her, I realized that I test very closely to the condition known as aphantasia, which means that I lack almost all visual memory. When I recall a past event, I remember largely in narrative and emotions rather than images. As a result, I am extraordinarily careful with what visuals I do include in my stories and novels, often focusing as much as on what is not seen as what is noticed. Because I have no control over how my readers experience their memories in real life, I felt emboldened by the opportunity to explore a multitude of literary styles via the memories in my book.

Something that these stories cleverly call out is that under oppression and censorship, one never really knows what will cross the threshold because the threshold is constantly moving. What effect does a shifting goalpost have on the freedom of expression?

I’m so glad that you caught that. I am fascinated and terrified by the ambiguity of censorship, and I wanted readers to recognize how authoritarian power can be exercised through uncertainty, amplifying the scope of censorship beyond even its original intentions.

As the narrator grapples with the memories left by his mother, I wanted him to question why certain memories were banned. Because in reality, it’s rarely black and white. How close to the red lines do you really want to get, especially if they’re always shifting? What if you belong to an identity group that is less powerful? What if you cannot risk losing anything at all? Another element I wanted to explore was how the very ideas once celebrated can later be disowned. Especially via “The Islander,” in which the narrator graciously accepts that the very Memory Epic which has just won an Oscar-esque award might be banned in the future, I thought it was critical to highlight the cyclical nature of censorship extremely early in the book.

Many of your characters, including the protagonist, go against the grain in a number of ways, while others reinforce or benefit from the government’s control. What interested you in the ways that humans meet oppression, censorship, and surveillance?

One significant influence for These Memories Do Not Belong to Us was Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go. That book wonderfully explores the phenomenon of resignation, mirroring the fact that when people are dealt a bad hand, they often work to make the best of it rather than challenge the system. As an immigrant, I very much identify with that mindset. I think the characters in my novel are all trying to survive and make the best of their situations, irrespective of whether they may be reinforcing the government’s power.

Only, as the novel explores, sometimes the only way to survive is to resist. Even if all that means is remembering.

Ultimately, are there things in this world that should not be ownable? Through writing this book, I decided that memories and lived experiences are things that should remain off-limits, no matter what the laws of Qin say.

The book is titled These Memories Do Not Belong to Us but closes with the line “It belongs to us all. I promise you: it will always belong to us all.” Tell me more about this juxtaposition, and what you hope readers will leave the novel with.

That contradiction is at the heart of what I’m trying to explore.

Growing up under capitalism, studying it, working within it, I thought a lot about the idea of ownership as I was writing this novel. Ultimately, are there things in this world that should not be ownable? Through writing this book, I decided that memories and lived experiences are things that should remain off-limits, no matter what the laws of Qin say.

We must protect our stories. Even personal memories can belong to our shared humanity, which is why the narrator ultimately releases all the memories. In that moment, the memories really do belong to everyone and no one. I believe that we’re at a particularly precarious political time, especially as new technologies increasingly take over the responsibilities of remembering for us via algorithms, digital archives and AI.

Please take care of your memories. Treasure them when we still can. They are invaluable, even if we have yet to enter an age of memory capitalism.

Born in Shanghai, Yiming Ma is the debut author of These Memories Do Not Belong to Us. He holds an MBA from Stanford and an MFA from Warren Wilson College, where he was the Carol Houck Smith Scholar. Ma spent a decade in the tech and finance world working in New York, Toronto, London and South Africa before writing his first book. His stories and essays appear in the New York Times, the Guardian, and elsewhere. His story “Swimmer of Yangtze” won the 2018 Guardian 4th Estate Short Story Prize.