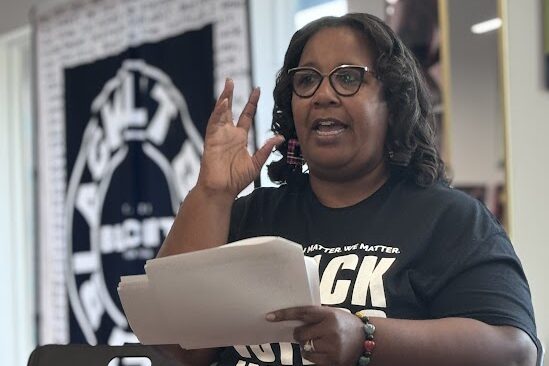

Joan Donovan, an award-winning sociologist who founded the Critical Internet Studies Institute, is known for her work studying media manipulation, extremism and disinformation campaigns. We talked to Donovan about how political disinformation has shifted from shadowy social media accounts to an open and brazen strategy.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What role do you think disinformation played in the 2024 election?

The biggest disinformation campaign of the year begins a few days prior to the debate between Kamala Harris and Donald Trump. When Trump proclaims during the debate that “Springfield migrants are eating the cats and dogs,” this was a classic form of disinformation where someone in power points the blame for problems in society on groups of people that cannot represent themselves, do not have access to media, are not in positions of power, and you demonize them. You create an aura of inhumanity around who they are. They doubled down, and J.D. Vance acknowledged to some degree that the narrative is what mattered more than the actual events.

This disinformation campaign was executed to make Americans feel as if Trump was going to solve a problem – the issue with people coming over the border – that has been an intractable issue since the dawn of America. There are other things that were up for debate – the tariffs, the grocery prices and things like that. Those are within the bounds of normal political debate. But this particular campaign was around migrants – not just the right for people to be here in the U.S., but the quality of life for people, and when they’re identified as being these monsters, it went down very quickly.

What do you think is different about how disinformation spreads now compared with 2016 and even well before that?

As I think about the last nearly 10 years of my research around these issues, you go through cycles. [In] 2016, people are very focused on this notion of fake news. They realize that the internet is essentially full of spam, and there are different ways in which stories that are novel and outrageous are combined to create attention. This attention has not just importance for politics, but it becomes its own industry. There’s money to be made in spreading outrageous storylines, and so it’s not just Macedonian teenagers being paid to post things like “the pope endorses Trump.” But there’s also an undercurrent masterminded by people like (longtime Trump lobbyist) Roger Stone and (Republican operative and former Trump administration chief strategist) Steve Bannon positioning Donald Trump as this outsider that can “drain the swamp” or “build the wall.”

The purpose here is trying to get Americans to feel as if some kind of social change is going to happen if Trump takes power. By 2018, many of the platform companies have bought in that there’s some kind of issue here with what they want to focus on, which is “ABC” – actors, behaviors and content. And the researchers are saying, “Actually, it’s more than that. There’s ‘D’ – design, and the design of your algorithms that promote novel and outrageous content is destructive.”

You have this landmark study come out of MIT showing that lies travel further, faster on Twitter and penetrate more deeply than the truth. What’s interesting about that is these tech companies then have to orient themselves differently, and you even have under Trump, Congress starting to shift, and Congress starts to ask questions about the performance of algorithms in relation to conspiracy theories. That’s when power actually shifts.

By 2020 though, things had really shifted. The tech companies are clamping down on anonymous accounts. They’re breaking up botnets. They’re more savvy about how their advertising technologies are used in the promotion of disinformation campaigns. Government agencies get involved in looking at the way foreign operatives are using social media to attack U.S. public opinion. You start to see more institutions get involved with social media.

The issue really comes to its peak on January 6, 2021, from the summer of 2020, when Trump starts to say you shouldn’t do a mail-in ballot because there’s a chance your vote won’t be counted. It was a strategy that his team had come up with as a way to negate the results of the election, or to do some pretexting. He was able to pretext and get people to think that the election wasn’t going to be fair. When November comes and he loses, he’s able to double down on that. The most significant thing that happens in that moment is: what we know of social media is that it can mobilize large groups of people to get off the couch and do something in the world. This is the first time you have a sitting president using the internet to directly call their constituents out to act as his own private army.

Between November 2020 to January 6, 2021, we get a glimpse into the future of what social media offers as a tool for organizing society, and no longer are they relying on anonymous accounts to push this content. You have a whole range of people from Trump world locked in to this idea that the election had been rigged or stolen.

I did a study when I was at the Shorenstein Center looking at networked incitement and what reasons people ended up in the Capitol that day based on their affidavits and other court documents. What we found was that a lot of people went because Trump told them to. They were saying, “Our president is asking us to fight.” That’s something we don’t talk about enough related to social media. It’s not just a distribution system for speech. It helps people understand and moralize and create values around their actions, and it also helps them get organized.

What advice do you have for journalists who are covering the new administration, especially as the legacy media has lost the trust of people?

It’s going to be really important for journalists to stay close to the facts. What we know is that Trump is a propagandist. He loves to do the thing that creates the most outrage. Let’s take the Pete Hegseth appointment, or RFK Jr. These are incredibly controversial Cabinet appointments, and I think in the very short term, journalists have been doing a great job of digging into their backgrounds.

In the long term, the other thing that’s happening here is there is an intense suppression campaign by politicians to scare people from telling the truth, to scare them from using words like “racist” or “rapist” in their reporting, and that can become really career-defining for some journalists. Many journalists I’ve known over the years that do work on reproductive rights have been doxxed, they’ve been swatted, they’ve had to uproot their sense of safety because they’ve been targeted for their journalism.

It’s also incumbent upon journalistic organizations to provide advice on safety and security. Every journalist is going to have to come up with a security strategy so they can do the reporting in a faithful way. What we know about Elon Musk is when he sues, let’s say, the Center for Countering Digital Hate, he’s really just looking to deplete the resources of this organization. Nothing they’ve done is illegal, and the evidence that supports their reports are available for anybody to audit. But when someone has that kind of money, using it in lawfare campaigns is just one way that they can turn off attention to the harms that they’re causing. So I think not just a personal security strategy, but also a security strategy around liability insurance, whether you’re a freelancer or a book writer, or you might want to check in with your news organization and find out what the fact-checking is going to look like to ensure that you don’t get caught up in a lawfare campaign.

The last thing I’ll say is these tech companies are rotten to the core, and they also have a role to play here. Do not contact sources on X. DMs on X are not encrypted, which means that they are visible and available to anyone that has access at the company, and so we are not in a situation where these platform companies are like the telecom companies, where they can’t track your communication. It’s really important that you think about your journalistic practice in relation to the technologies that you use, and so as fast as you can, move conversations to Signal so that you’re protected and your sources are protected.

Joan Donovan is an award-winning sociologist and assistant professor of journalism and emerging media studies at Boston University. She is coauthor of “Meme Wars: The Untold Story of the Online Battles Upending Democracy in America.” Donovan’s research focuses on media manipulation and democracy. Her work has been showcased in outlets such as NPR, The New York Times, MIT Technology Review and more. She is the former Research Director of Harvard University’s Shorenstein Center on Media Politics and Public Policy.