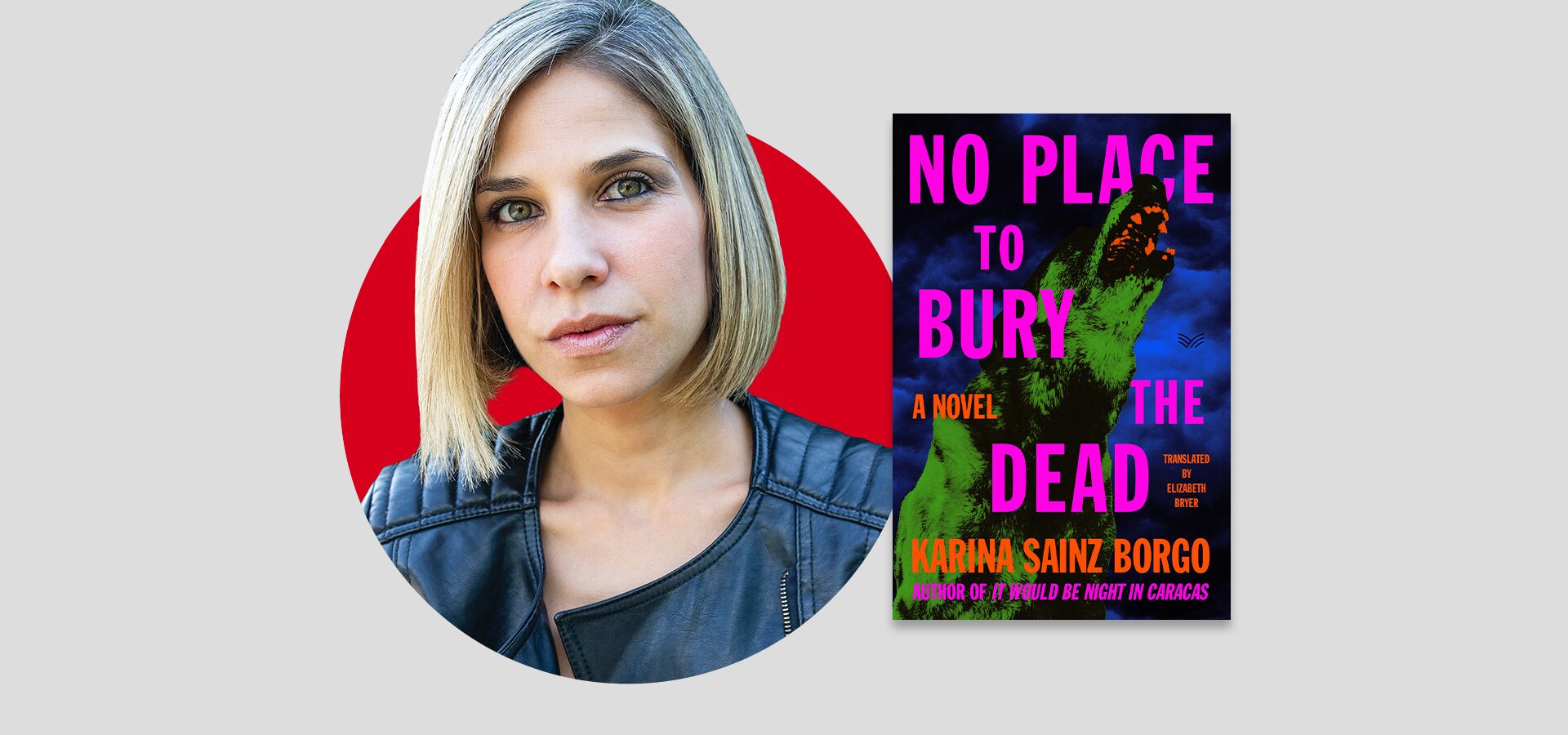

Award-winning journalist and author Karina Sainz Borgo’s latest novel No Place to Bury the Dead (HarperVia, 2024; translated by Elizabeth Bryer) tells a sharp story of belonging, dignity, and identity inspired by true accounts of the migrant crises. Fleeing a plague that leaves its victims with amnesia, Angustias finds herself caught in a fierce land battle between a vigilante woman who oversees the cemetery and violent gangs. As she seeks to bury her two sons, the novel asks: who has the right to bury their dead? And how far would you go to bury your loved ones?

In conversation with Digital Safety and Free Expression’s Program Assistant, Amanda Wells, Karina Sainz Borgo discusses the interplay of journalism and fiction, the politics of burial, and the international response to No Place to Bury the Dead. (Bookshop; Barnes & Noble)

In addition to being a fiction writer, you are a journalist, and No Place to Bury the Dead is described as “inspired by true accounts of the migrant crisis.” How did your background in journalism affect the research that you did for this novel, and how you told this story?

For me writing is like laughter or hunger. I like both. I could not do fiction without the gymnasium of journalism. Journalism teaches you to work with very few elements: very little money, very little time, very little space. It’s limited, it’s like you’re an infantryman and you’re moving forward with your helmet. And it helps you to operate, to amputate your leg when you have to amputate someone’s leg. Life is journalism, it is what irrigates, the capillarity, but you need literature to illuminate a new version of that world. I am 41 years old and I started in journalism when I was 17. Journalism has vaccinated me from rhapsodism, from sterile aestheticism, and has put my feet very much on the ground. Perhaps the only thing that I dislike about journalism is the truth, because a journalist is obliged to give answers, and a novelist is not.

The novel is fable-esque, and one of the things that contributes to this are the apt character names–Conseulo, for example, brings comfort to Angustias, Visitacion is often iconographically aligned with the Virgin Mary, and Alcides is the most powerful man in the region. How did you settle on character names, and how did that ultimately shape their development?

I have decided to turn to the elements of classical tragedy. Antigone as a plot has always disarmed me: it radiographs a sick society and the capacity of individuals to resist moral poverty. I think that the basis of Antigone as a character, and as an allegory that gives life to these women, disobeys a law to do what she considers just and right. I use the element of the virgins, because it alludes to the ‘passion’ in its western iconography. In this allegorical territory proposed by the novel, good and evil are interchanged. This novel seeks the notion of the other as someone in need of pity. We are incapable of compassion, we live compartmentalized in a world bent on its own foolishness and unwilling to compromise on its prejudices and obsessions. In this novel there is a great plea for friendship and solidarity. To memory and civic courage.

Elizabeth Bryer writes in the translator note that she wanted to maintain the “effect of a particular time and place without making it of that time and place.” Some of the most jarring moments of this novel were the reminders that this is very much a modern story–like when we see the years on Visitacion’s tombstone, or encounter mentions of the Internet. Why did you want to create a generally unbounded world, and how did you decide when to connect the story to modernity?

I conceive identity as a hybridization. For example, my childhood sensibility is telluric: my language, my vision of landscapes, my memory of smells, even the way I count is very Caribbean. I was born in Caracas, Venezuela. However, my balcony to the world for the last 15 years has been Spain, even Europe. I like to create a mixed, confused world. I am attracted to allegory. Some of the writers I most admire have worked with it, for example J.M. Coetzee.

This novel seeks the notion of the other as someone in need of pity. We are incapable of compassion, we live compartmentalized in a world bent on its own foolishness and unwilling to compromise on its prejudices and obsessions. In this novel there is a great plea for friendship and solidarity.

Similarly, the novel takes place in an “unnamed Latin American country.” Why unnamed?

It has a name. The town is called Mezquite, which is the name of a tree very present in the work of Juan Rulfo, who inspired the spirit of the book. I insist: the symbolic is sometimes much more powerful.

The original Spanish novel was titled, like Visitacion’s graveyard, “The Third Country.” Why did you title the English translation of the novel “No Place to Bury the Dead” instead?

The third country is the resulting space in a border territory. In this novel there is a border between the living and the dead, the good and the bad, oblivion and memory. I think the English translation is very accurate. The place where the dead rest is political. It is important. It is memory. Memory is the foundation stone on which we can build something lasting. Most totalitarianisms have tried to manipulate it, to use it for ideological purposes or directly to dynamite it. The mass grave as an image is very explicit: when a society is incapable of giving a human being even a piece of land and a box so that vermin do not eat it, there is a problem. When you bury, apart from the fact that you are doing a restoration, you are creating memory. Someone has to know that someone died there and why they died, what were the reasons why they died.

Land is one of the central queries of the novel. The territory of The Third Country is caught up in a bitter and deadly ownership dispute, and you write that there is a “true injustice” to the land. How did the geography and concept of a “border zone” impact the setting of No Place to Bury to Dead?

Absolutely. In my novels, the land is everything. Landscape is everything. For as long as I can remember, I have been writing to dig my own land, to make sense of the tropical and fierce world in which I was born. It accompanies me. It is with me. It defines me. I have not returned to my country for almost twenty years and the trip that motivated this book was directly to the border, on the Colombian side, in La Guajira. That encounter shocked and conditioned me.

A society says a lot in the way it kills, but it says even more in the way it treats its dead. The denial of a burial is a denial of civility, of the most elementary compassion and the right to memory.

Land is also inextricably linked to the right to bury the dead: before Angustias buries her sons in The Third Country, she remarks “that land was not mine, but it was land.” What role does ownership and belonging play in the ability to lay the dead to rest?

Exactly. A society says a lot in the way it kills, but it says even more in the way it treats its dead. The denial of a burial is a denial of civility, of the most elementary compassion and the right to memory. It is a right that the protagonists demand and defend. It is their epic.

No Place to Bury the Dead has now been translated into a handful of languages, including Portuguese and Italian. Has anything surprised you about the international response to this novel? Have you found that different readerships react in different ways?

Yes, absolutely. I have been surprised by the positive and empathetic way it has been received in countries such as France, Germany or Italy, whose relationship with migrants is also complex.

Despite depicting so much death, the novel is bookended by life, beginning with the birth of Angustias’ sons who are the catalyst for her migration and ending with the birth of Consuelo’s daughter Milagros. What sparked your interest in the “blurred boundary” between life and death, and why did you decide to end your novel with new life?

I cannot conceive of life without death. It is a theme that is present in everything I write and I try not to lose sight of it. The arrival of a human being to life is as abrupt as his departure. In fact, Visitación Salazar says it in a passage of the novel: not everyone can be born, but we are all going to die.

I cannot conceive of life without death. It is a theme that is present in everything I write and I try not to lose sight of it. The arrival of a human being to life is as abrupt as his departure.

If you had to choose one thing for readers to take away from this novel, what would it be?

I want you to keep an idea in mind: What would happen if a higher power prevented you from giving a dignified burial to the person you love the most? What would you be capable of doing? Would you disobey the law? Would you confront evil?

Karina Sainz Borgo was born and raised in Caracas, Venezuela. She began her career as a journalist for El Nacional. Since emigrating to Spain ten years ago, she has written for Vozpópuli and collaborates with the literary magazine Zenda. She is the author of two nonfiction books, Tráfico y Guaire and Caracas Hip-Hop and the novel It Would Be Night in Caracas. Her latest novel, No Place to Bury the Dead won the the 2023 Jan Michalski Prize. She lives in Madrid.