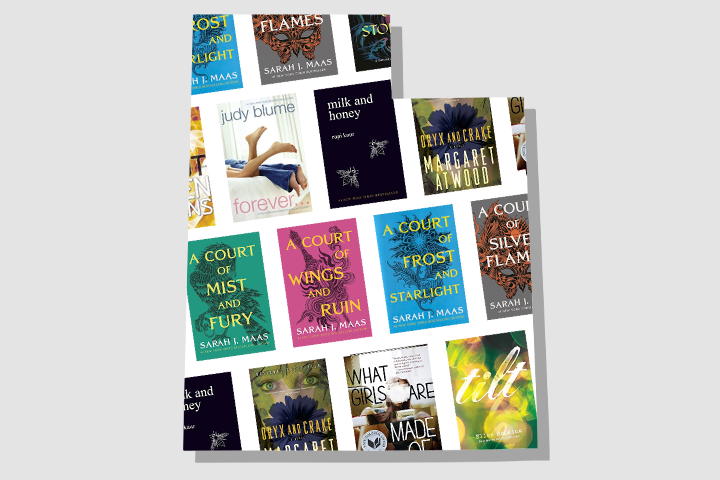

Yes, books are being targeted. Yes, they are being removed from shelves and discarded. Yes, they are being banned. But what is the human cost beyond the shelves?

A panel discussion last week, “The Hidden Cost of Defending Books,” presented by The Eleanor Roosevelt Foundation and SEAT and moderated by Kasey Meehan, program director, Freedom to Read at PEN America, featured author Ocean Vuong and activists Cameron Samuels and Becky Calzada, all of whom have stared book bans in the face.

“It’s a privilege to struggle for what you believe in. Some people don’t get that privilege,” said Vuong, acclaimed writer and a creative writing professor at New York University.

Vuong was teaching his class on books that are innovative, different, and difficult – and coincidentally the books that are historically banned – when, towards the end of the semester, a student informed him that his own book, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, was banned in Texas. “Marx says history repeats itself, first as tragedy, and then as farce,” Vuong said.

PEN America counted more than 10,000 book bans in the 2023-2024 school year, a record high, according to the latest report and analysis. Florida and Iowa topped the list, with Texas not too far behind.

“Censorship erases our histories and limits what’s possible, that’s the message that censorship is sending to our youth,” said Cameron Samuels, who led efforts against book bans in the Katy Independent School District in Texas as a student. “These book bans and censorship as a whole has never been this conversation over appropriateness in the classroom, but rather, they’ve been attempts to legislate people out of existence.”

Samuels is now organizing a coalition of Students Engaged in Advancing Texas (SEAT) to demonstrate youth visibility in policymaking. As someone growing up queer and disabled on the spectrum in Texas, books offered much needed comfort and recognition to Samuels.

The official Katy ISD website claims the removal of 14 titles found to violate the “pervasively vulgar” standard per their policy, while The Texas Freedom to Read Project has recorded 34 books since just August of 2024 in the school district. With 74 schools and more than 92,000 students enrolled, they have not only pulled books from shelves but also cancelled author visits.

Samuels shared that in their early days of activism when they stood up against book banning in school board meetings, theirs was the only voice against it; walking up to the lectern after a series of speakers spewing hate, all they received were stares and silence from the room.

“I like to say often that those stares that they gave me were stairs to climb on,” Samuels said.

From there a national movement against book banning gained momentum, getting the attention of policy makers, publishers, and non-profits.

On yet another frontline are librarians.

“I know we are seeing librarians either leave the profession because they can’t deal with this, or they’re not being treated as professionals,” said Becky Calzada, president of the American Association of School Librarians. “We also are not seeing many people going into the profession, which is a problem. So there are hidden costs.”

Calzada is the District Library Coordinator in Leander, Texas and is a co-founding member of Texas FReadom Fighters, a grass-roots led group of librarians launched back in October of 2021 in support of intellectual freedom and to highlight the positive work of school librarians.

“Oftentimes we hear, oh, that book is not banned. You can go buy it wherever, at a bookstore,” Calzada said, adding that such rhetoric fails to recognize the severity of the situation and is based on the assumption that people have funds to purchase books and internet access to just get it online. “There’s so many in Texas, so many rural areas that don’t have access or are even close to a library, whether it’s a school library or public library, and so there’s also a lot of misinformation about kinds of censorship.”

Born and raised in Texas, Calzada’s career as a librarian has spanned three decades. She said she now sees self censorship happening because school librarians feel like they shouldn’t buy a certain book fearing it might be challenged. “There’s so many hidden impacts that we see, and so many that we don’t even know are documented because there’s no way to capture that,” she said.

But young people and their activism, litigation and lawsuits to change legislation, and authors continuing to do their work gives the panelists hope.

“I have never seen a more politically conscious generation in my life,” said Vuong. “They have taught me that nothing is off the hook. They’ve let us into their movements, and they’re teaching us how to fight for ourselves. And that has been such a revelation to me as a teacher and just as a person.”

Vuong said as an educator, the cost of book banning is immediate. “If you take representation and actions that are different outside of the literary lexicon, you’re depriving the reading public and writers of that possibility of making real, historic change as artists,” he said. Vuong is afraid that students might not get inspired by books in their early years because they don’t see themselves represented and fail to get the opportunity to pursue their passions, especially as writers.

“Politics is ever evolving, and somehow our freedom to read has inherently been a political issue over time,” said Samuels. “We as students are standing up on the front lines, because we have an imagination for the future. We aren’t limited by the status quo that’s not helping us.”

“It brings me closest to this idea that we are in this aporia. We are a country of contradictions, and it will never be smooth, it will never be easy, it will never be clear,” said Vuong. “But that is what literature affords us, complexity through dialog, right?”