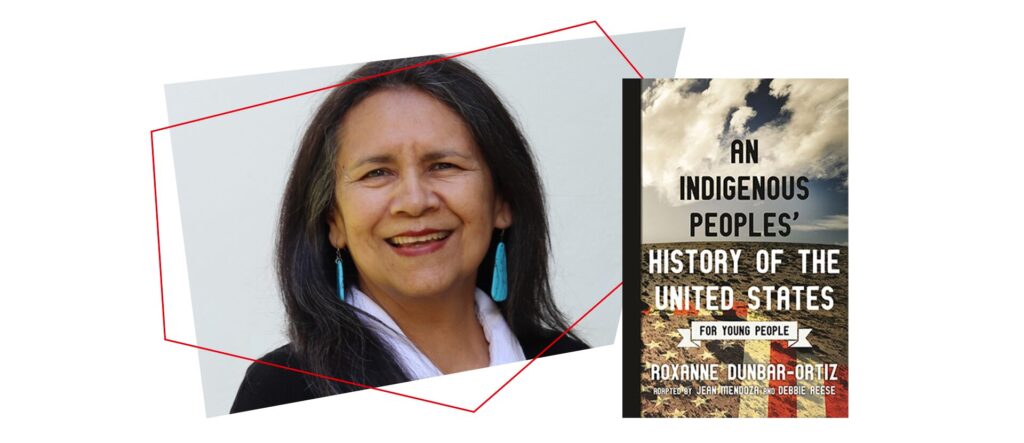

At the tail end of another year that has threatened and targeted books by Native Americans–from book bans to incorrect reclassifications–the work of Dr. Debbie Reese becomes extremely important. Her website, American Indians in Children’s Literature (AICL), is a repository of information on Native American heritage that acts, at once, as both an archive and a record, especially of misrepresentation of culture in literature.

For the last several years, Dr. Reese of Nambé Pueblo, a writer, scholar, and educator, has tracked bans of books related to the lives of Native Americans. Last month, she joined the successful call by freedom to read advocates for Montgomery County, Texas, to reconsider its decision to reclassify from juvenile nonfiction to fiction a celebrated book that presents the Indigenous perspective on European colonization.

For Native American Heritage Month, Dr. Reese discussed with PEN America how she first came across stereotypes, how to change and shape the discourse, and why it is important to get it right in children’s literature.

You started AICL in 2006 as a resource not only for Native Americans, but to introduce everyone to the ways of the Native peoples. What drove you to create this space, and especially as a blog on the internet, a newly emerging medium?

At the time I was an assistant professor in American Indian Studies at the University of Illinois. I realized that my articles and book chapters were going to be behind paywalls or in books that were too expensive for teachers. And, I had been an active participant on internet listservs about children’s books, but they were declining as blogs started to emerge. I decided to create American Indians in Children’s Literature as a way to make my research and perspective available to anyone with an interest in depictions of Native peoples in children’s books.

What are some of the gaps in talking and writing about Native American history that you have come across while studying and researching, and how do you think this has changed over the years?

Our presence as peoples of Native Nations that still exist and pre-date the United States continues to be a huge gap. In too many materials we are confined to the past, seen as a monolithic cultural group of uncivilized and primitive creatures, rather than as unique sovereign nations whose leaders entered into diplomatic negotiations with leaders of other Native Nations, and then later with non-Native Nations from Europe, and then, of course, with leaders of the U.S. In recent years, Native people have used social media to make interventions in public conversations.

Why did you think it was important to focus on children’s literature while spreading the broader message of the Native peoples?

I went to graduate school at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign. I intended to study family literacy. There was a much-loved stereotypical mascot that people defended by saying it taught them about Native peoples. They said those words to actual Native people on campus who told them it was stereotypical. One student I interviewed said I was the first Native person he had ever spoken to. I asked him what he thought a Native person would be like, and he sheepishly said that he thought there would be some sort of aura. I had many interactions like that, with everyone from young children to adults. Their defense and embrace of the mascot, my interest in literacy, and my interest in children’s books prompted me to take a different path with regard to what I would study. Instead of family literacy, I started to look critically at depictions of Native peoples in children’s books and saw book after book that had stereotypical imagery of Native peoples. Stereotypes in children’s books, or as sports mascots, were–and are–shaping what non-Native people thought–and think–about us.

Recently Montgomery County in Texas reversed its decision to move Linda Coombs’ book, Colonization and the Wampanoag Story, which presented the Indigenous perspective on European colonization, from juvenile nonfiction to fiction. What are your thoughts on the whole situation? How can such instances be avoided in the future?

The fact that people knew that decision was wrong and spoke up was significant. With the 2024 election, I think the future will bring an upswing in book bans and challenges and a decrease in people who speak up out of fear for their safety. In short, I’m uneasy about the next four years but I will continue to do the work I do. Looking at photographs of Native children reminds me that we are still here because our ancestors fought for us, over and over.

More books by Native American authors on Bookshop.org

Since 2021, you have also been keeping a track of all the books related to the lives of Native Americans being banned in the United States. Why did you think this record-keeping was important, and what are some of the key takeaways?

As I followed recent news stories about books being banned or challenged, I was not seeing Native titles. Leaving us out of news coverage, in effect, erases us from the conversation. Erase is a strong word. It implies that something was written down and then the person who did that writing decided against it and so, erased it. I don’t know if that happens or not in coverage of book bans, but my work is about making us visible. And so, I started that log so there would be a record that says Native writers are being banned or challenged.

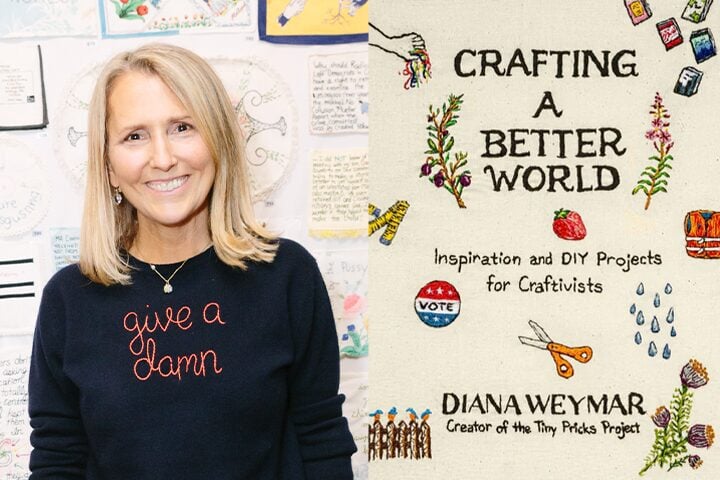

Your own book, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, has been the target of book challenges. What is your response as a writer and researcher?

In my research of books being banned, I see a lack of detail. I think people who challenge books are not actually reading them. Instead, they seem to be finding lists someone else made, and then submitting titles and using a cut/paste method that labels the book as “divisive.” Our book is honest. It has things in it that a person could quote as being “divisive” but we aren’t seeing details for why it is being challenged. In essence, it seems that our existence and our exercise of speaking about our history is seen as “divisive.” That does not bode well for the well-being of anyone. These are facts that should be known to all people.

What do you wish people were talking about more when it comes to Native American heritage and culture? How would you like to change or shape the discourse as it exists right now?

In every workshop I do with teachers and librarians, I emphasize the use of present tense verbs and tribally specific information. When introducing a book, I encourage them to say, for example, Chooch Helped is by Andrea L. Rogers. She is a citizen of the Cherokee Nation. I really want people to move away from books labeled as “folktales, myths, or legends” because most of those are written by non-Native people who do not understand those stories and what they mean to us. Lack of understanding means they change them to fit within white expectations. An example is Turkey Girl: A Zuni Cinderella Story by Penny Pollock. Turkey Girl has meaning to the Zuni people but she changed that meaning to make it into a Cinderella story. As such it misrepresents Zuni – the place and the people, too.

What changes would you like to see in the children’s literature and curriculum sphere going forward as newer generations enter the study-space?

I’d like to see curriculum materials that include Native-authored stories. Most of what I see is older books by non-Native writers. And I’d like to see books like Coming Home: A Hopi Resistance Story in school and classroom libraries, and in packaged materials from textbook publishers. It is a new book (pub date Nov 2024) in which a Hopi author talks about his grandfather’s time at a government boarding school. When people think of “boarding school” they imagine elite schools on the east coast but it is important they know that boarding schools for Native people existed, and that they were meant to “kill the Indian and save the man.” The schools did a lot of damage to the well-being of our nations, but we resisted. The point is not to romanticize what we went through but to teach kids what the government is capable of doing to innocent children so they grow up with an honest appraisal of the United States, past and present.

What books by Native American authors would you recommend?

Each year, we put together a Best Books list. On our annual list you’ll see graphic novels, board books, picture books, books for middle grades and teens, and even a few books for adult readers. As you look over them you’ll notice that most of them are set in the present day. That’s because Native writers are creating books they wish they had when they were in school. In the last year or so, I’ve been keen on books by Laurel Goodluck. Her picture books are great!