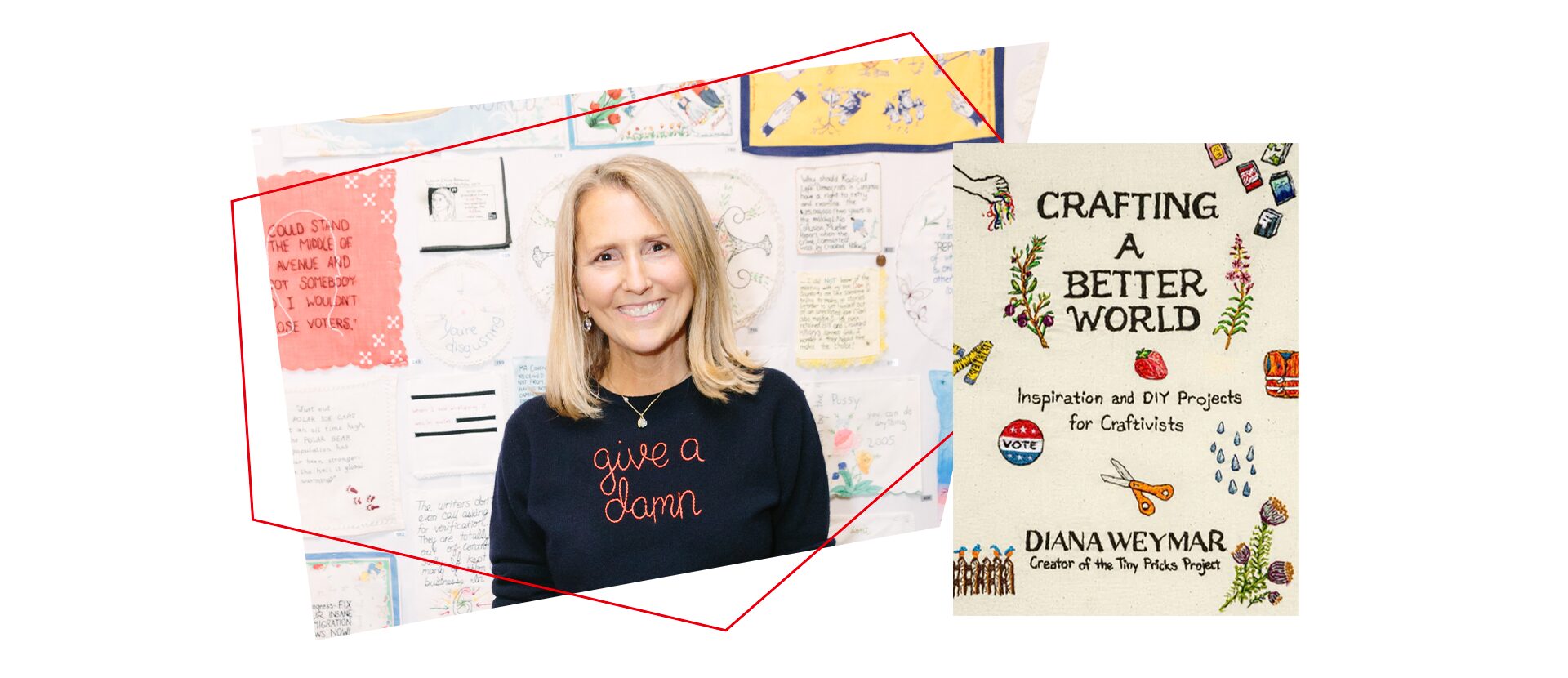

Though deeply unhappy about his presidency, artist and writer Diana Weymar did not want anything to do with Donald Trump. That is, until he claimed he was a very stable genius in 2018. Instantly pricked, she found some heirloom textile, took out her needles, stitched his quote and posted it on Instagram. The photo of her handmade creation instantly blew up and Tiny Pricks Project (@tinypricksproject) was born, where not just Weymar, but hundreds of creators came together to contribute their stitch-work. Today with over 120k followers on Instagram, the grassroot movement not only made Weymar realize the importance of craft in activism, but led her to a vibrant community of fellow craftivists. With another election cycle approaching, she collaborated with some of them and others working for change – including PEN America – bringing to life Crafting a Better World (Harvest, 2024), a book that celebrates craft and also calls on its readers to get together and get crafty.

- You come from a background of writing and being immersed in the creative fields. Was writing this book an extension of your previous work or was writing this different from anything you have done before?

This is very different than anything I’ve done, but in a way, is also the combination of everything I’ve done. I grew up in the wilderness of northern British Columbia to parents who left the U.S. in 1970 for political reasons, and I’m a parent of four, and I became interested about a decade and a half ago in art therapy. The craft-based approach to processing issues really comes from a childhood without electricity and indoor plumbing and kind of making things both philosophically and literally to solve problems. And then the social media part is really how you can overcome physical obstacles to connecting. I started a small, grassroots project. It grew on social media and then that ends up connecting you to people like PEN America and other writers and artists and politicians.

- In your introduction you say, you are “deeply sensitive to how language and imagery is used.” What was the process like for this book, where your use of language and imagery is central but not directly on the page? How did this make you see language differently?

I try to put things as directly in the physical form as I can. But in terms of this book, what I do is to scale things down into something very small that hints at something larger. My hope is that people who don’t have the exposure I’ve had, or access to these different ideas, can look at the small thing and want to go bigger. Language has a small tipping point. So the Tiny Pricks is really this kind of prick, like something pricking you on the arm, saying, “Here’s a small thing.” We live in a really strange world, so it’s just taking those tiny bits of language and asking people what they see or what they read or inviting them to slow down. I think language has the ability to impact how we move and how quickly we process. We don’t dispute what’s being said, we dispute what it means. I’m very interested in just this one way of capturing a bit of time and hopefully sharing something that’s new and interesting or old and difficult and controversial, however it is, there’s enough of a pause there that you just see a little bit differently.

- As a writer and creative, how important was it for you to create something tangible to process the strong emotions you were feeling? Why do you think that rage expressed itself so materially?

I think making is processing. Making is a physical act which involves your body, and it doesn’t involve your mind in quite the same way that reading does. When you get to craft, it’s repeating a process–there’s ways in which the mind goes in and out of the experience. By definition, the process of making is an emotional process, as is moving, and I think it’s a very natural impulse for me to feel that there must be some way to connect and share this process. Living in this world right now, I think we’re all looking for connection, and Craftivism is a very direct way of sharing and witnessing what you’re feeling with others. We’re so quick to summarize everything and everyone because we’re exposed to so much. To be able to take one thing and process it through a physical act of making something, I think, is one of the ways of guiding the body through the experience and taking the mind along it.

We live in a really strange world, so it’s just taking those tiny bits of language and asking people what they see or what they read or inviting them to slow down. I think language has the ability to impact how we move and how quickly we process. We don’t dispute what’s being said, we dispute what it means.

- What are some creative ways to talk about book bans?

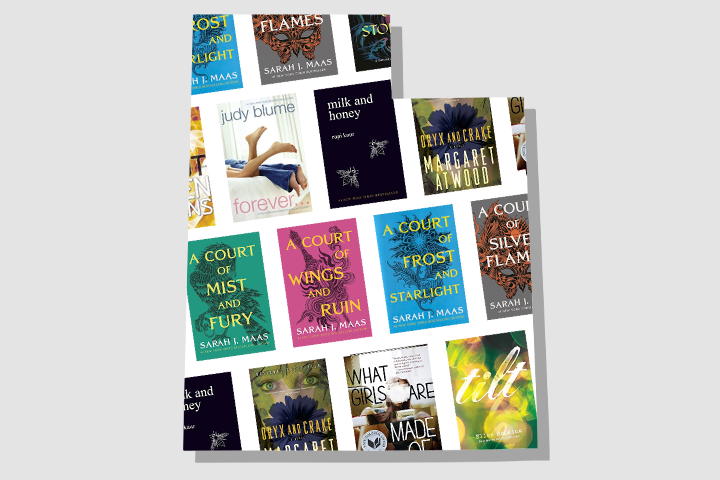

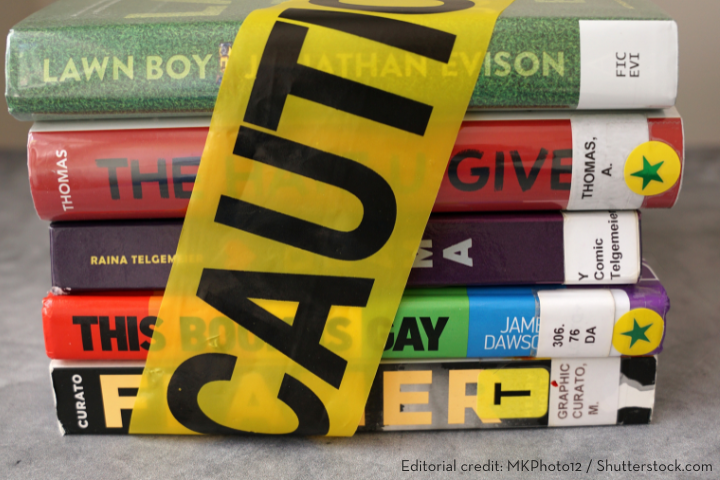

When you think of craft, you may not necessarily think of PEN America, but I think there’s very few things that are more important than reading books, and freedom of speech. This is what we do–we create stories, and so the book is really designed to remind people of the things that we have in front of us, and to not take them for granted, but to protect them and to be actively engaged in the process of preserving them. And one of the ways you preserve things is by carrying them forward. We talk a lot about the books that are banned, but what about talking about the books that aren’t banned, that we love? Yes, focus on the books that are banned, but what about promoting and hyping books in general? You know, I’ve noticed that people have dropped off from talking about the books they’re reading. So get around bans by celebrating books, buy banned authors, and promote reading overall. I think it’s that simple.

- In your book craft becomes a communal language. How important was it, even when you started the Tiny Pricks Project, and subsequently this, to reach out to the larger world, call on like minded people, and curate a collective experience?

Unlike a book that is written usually in isolation, alone, and then you publish it and bring it out, craftivism and Tiny Pricks Project unfolded in real time as it was being built. I didn’t intentionally set out to create a community grassroots movement. I just was trying to do this myself, and couldn’t possibly do it alone. So when you realize you can’t possibly do something alone, you have to ask for help. I think writers are able to leap ahead of things and predict and create a sense of what has already happened. But I’m really staying in the moment just fast enough, long enough to grab something. We have another election. Books are still being banned. Everything we were fighting for we are still fighting for, and plus some. It has to be public because it is too big, and I think there’s sort of no point in doing it alone. Activism is inherently such a group thing, it comes together in unity.

- Writing is such a singular activity. What was the response when you reached out to people who are featured in the book, especially when you brought up the term ‘craftivism’ – crafting as a form of resistance and a form of healing?

I think people in the book understood the two things about the reach and what I was asking for. One, the timing was really important, it’s a very quick turnaround to get the book out in time for the election. And the other thing was that everyone understood, because of the work they do, that there’s a need to process and to heal. I picked these different organizations and individuals, because they were already doing what I was writing about. So they may not use the term craftivism, but they’re already doing it, and in many cases for much longer than I’ve been doing it. So people were very positive.

Unlike a book that is written usually in isolation, alone, and then you publish it and bring it out, craftivism and Tiny Pricks Project unfolded in real time as it was being built. I didn’t intentionally set out to create a community grassroots movement. I just was trying to do this myself, and couldn’t possibly do it alone. So when you realize you can’t possibly do something alone, you have to ask for help.

- I was completely amazed by the range of people you collaborated with–from writers and illustrators to performers, activist groups, an ecotherapist to a fire ecologist! How did you gather the host of wonderful creatives and thinkers and activists featured in your book?

I could do five books, because I draw inspiration from so many different places. There were some things like book bans, where I could get an author whose book was banned or an organization to say, remind us, here we are, here’s a structure, and here are the things that you can do. Some people I have worked with, some people I just heard about and thought, “Oh, they’re amazing.” The fire ecologist is my ex step sister, but I happen to just be fascinated by what she does–the idea that you can rethink and reapproach indigenous practices and apply them to a situation we’re in to remind us, because craft has such a history of tradition, that you were not the first that’s been facing some of these things. They were just all people who I felt some connection to, whether I knew them or not, and whether I worked with them before.

- Social media has been a powerful tool in helping spread the word about your project. In the book, we see a glimpse of its positive power through the story of Rebecca Seaver or Mx Mona. In an age where it’s being used for both good and harm, how has your experience been on those platforms?

I have to say, from the outset, that my book doesn’t exist without social media, specifically, Instagram. I understand that I am creating content for someone else, a company, and I don’t necessarily own it, but to be able to reach the number of people that I’ve reached within the constraints of my own life, I think the platform itself has the potential to be a great equalizer for redistribution of access. I think it is a very difficult environment, but I think the most toxic part of the environment is the frequency with which people use it. Craft and stitching doesn’t draw the most divisive people. I’m criticized for what I don’t say–for not weighing in more heavily on different issues, specifically the war in Gaza and the terrorist attack, but also the devastation and the sadness and grief and anger and rage and and just it’s so hard to thread that needle.

- Later in the book you both look forward and back. “We are transitioning to virtual experiences, away from the handmade, and to creative tools with an intelligence of their own. Bringing what was made before into new spaces (social media, virtual reality) is a way to integrate past histories and new technologies.” How important is preservation, especially of art? Is this book a way of doing that? What spaces or forms do you think it will be preserved in?

For me, preservation is acclamation, so bringing forward a traditional craft into a very contemporary space allows you to reactivate it back to life. I’m interested in historic practices, in how that practice can be used now. What is interesting about looking at something that you heard an hour ago stitched and posted on social media? The craft of textile up against this non physical, virtual space. So I’m interested in the intersection, or often it’s sort of a collision. It’s meant to sort of ask, how are you presenting information? Are you creating information? How are you processing information?

I also wanted the book to really have a wide focus, so you could see how many different things there are out there that you can do right now in this political climate. You know, for introverts, for extroverts, for people who work with certain kinds of materials, or people who don’t work in materials but want to be activists. Craftivism can apply to a lot of different processes that don’t necessarily lead to a physical object. I really wanted to get them all together in one place and say, look at this sort of amazing work.

- There are a lot of ways that readers can get involved in this book. How would you like to see people come together now for craft and craftivism?

I hope it encourages people to feel that they’re comfortable reaching out to other people to say, let’s do this thing together. It’s meant to urge you to want to reach out to other people, but also, if you are not inclined to do that, to feel comfortable on your own, knowing that there’s a community of people who do these sorts of things. You’re not alone in this desire to make something. And I also wanted the book to really have a wide focus, so you could see how many different things there are out there that you can do right now in this political climate. You know, for introverts, for extroverts, for people who work with certain kinds of materials, or people who don’t work in materials but want to be activists. Craftivism can apply to a lot of different processes that don’t necessarily lead to a physical object. I really wanted to get them all together in one place and say, look at this sort of amazing work.

- Based on your childhood, you said, “Art connects me to the unknown,” and there is a lot of talk about crafting as a means of survival. As we gear up for an intense election cycle, how important do you think it is to be political at such a time as this?

I think it’s very important to hold this space to encourage people to encourage other people to vote. Keeping yourself calm and sustaining your enthusiasm and keeping yourself focused and understanding that you just have to do these small things that we need to keep this process alive and to have complete engagement. Even if your politics are different than mine, still, it would be better to have any vote. And so I think this book is to suggest that if you can find ways to participate in your life in different ways, you will also show up for this process.