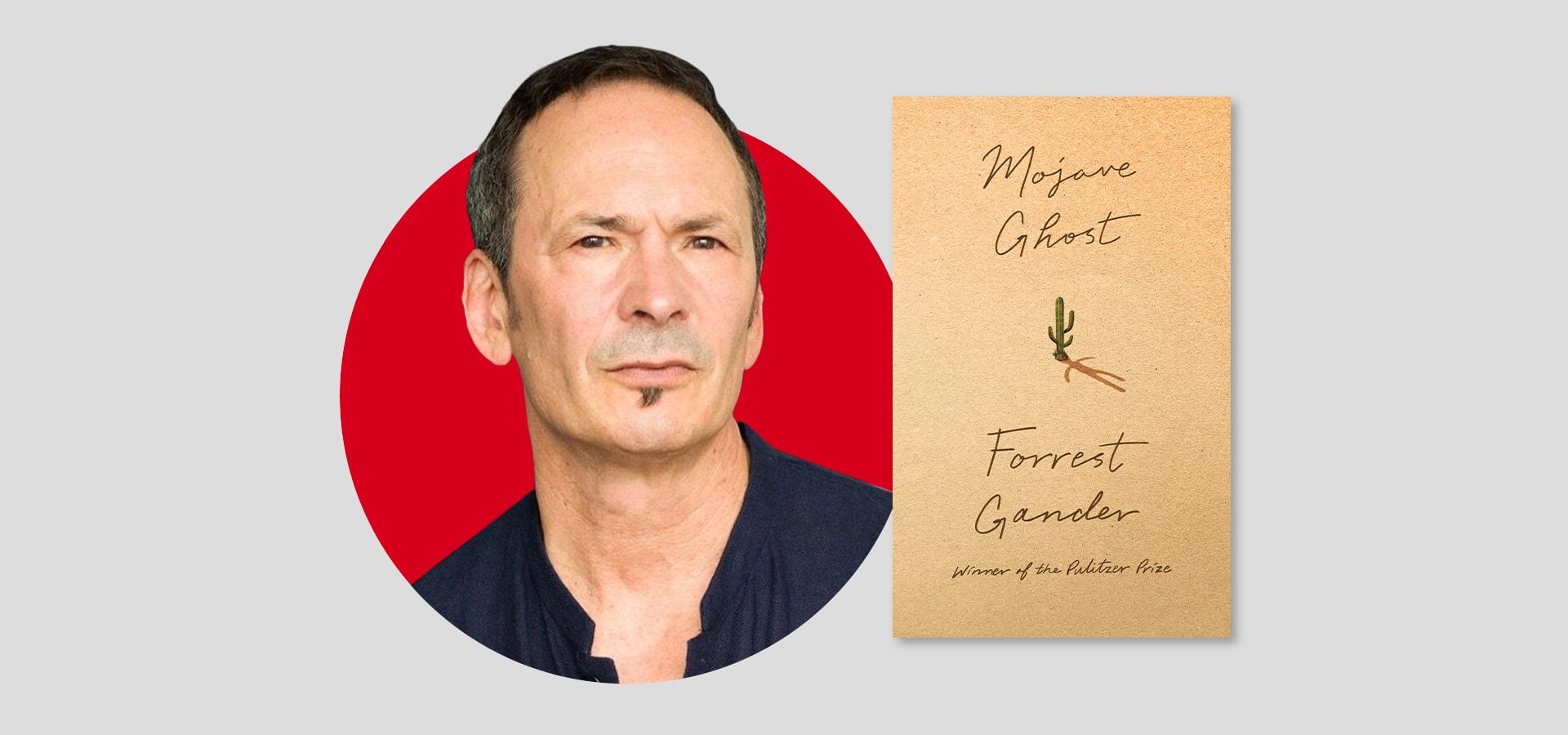

Exploring a new form, Forrest Gander’s Mojave Ghost (New Directions, 2024) is a novel-poem that intertwines place, memory, and perspectives. With a background in geology, Gander details the fauna and flora of the Mojave Desert from his childhood with present-day meditations on love and loss while hiking the San Andreas Fault. Displaying vulnerability through intimate details and an honest portrayal of complex emotions, each stanza is connected by a web of relationships reminding us that we are not alone even when we grieve.

In conversation with World Voices Festival & Literary Programs Coordinator, Sarah Dillard, Forrest Gander reflects on the self as interchanging perspectives, desert climate, and the fusion of identities when two people are in love. (Bookshop, Barnes & Noble)

1. There have been novels written in verse by Elizabeth Acevedo, Kwame Alexander, and Ellen Hopkins to name a few. What’s the difference between a Novel Poem and a Verse Novel, if there is one? Why did you choose this form?

Mojave Ghost needed a more direct, more intimate address than I’ve used before, and the voices of characters, named and unnamed. A less acrobatic syntax and sentencing. Sometimes, it may seem close to prose. All of that makes this book distinct—novel in the sense of new—from any other that I’ve written. But there’s also a clearer narrative and geographical trajectory in this book which is, essentially, a single extended poem with a coda. The book begins in the Ozarks of Arkansas and ends in California’s Mojave Desert. There’s a gradual movement along the San Andreas fault toward Barstow, the city of my birth. And rather than through stanzas, I think of the book’s structure as developing mostly through sequences of scenes.

2. You start Mojave Ghost with a poignant phrase on the first page: “There is nothing in me now / of what I was before.” What is your relationship to yourself in the past? As a writer who has published for decades, how do you view your previous works?

I guess I tend to judge myself as a writer by what I’m doing now or what I intend to do next, not so much by what I’ve already written. One hopes always to exceed oneself. To write better than before. What is your own relationship with the past? I think that’s one of the questions Mojave Ghost asks repeatedly. Isn’t the past a constant, fluid, upwelling constituent of the present?

The objective world isn’t as directly accessible as we might imagine, but is constructed on the basis of constraints on our perception and on our language.

3. We often think of STEM and Creative Arts as being on opposite ends of a spectrum. However, you have a background in geology, intersperse fauna and animals, and quote Pascal. What connection(s) do you see between the two?

As I’ve noted before, history reminds us that any scientific truth is a construct and a contract with its time. Neither good poetry nor good science corroborates the assumption of presumed values. And the objective world isn’t as directly accessible as we might imagine, but is constructed on the basis of constraints on our perception and on our language. We know that language, perception, and memory are inextricably interdependent. So there’s no one real world toward which science proceeds by successive approximations. As the poet William Bronk wrote: “And oh, it is always a world and not the world.” There’s simply no neutral, objective point of view.

And then again, poetry doesn’t simply supplement the rational intellect, but provides inherently and sometimes incommensurable forms of insight. Because its meanings are neither quantitative nor verifiable, poetry may offer different, subtler, and more complex expressions than the language of science and commerce. As Ludwig Wittgenstein noted, “We feel that even if all possible scientific questions be answered, the problems of life have not been touched at all.”

4. Desert climate is unpredictable and changes vastly from valley to mountain. How did growing up in the Mojave Desert prepare you for life’s ever-changing journey? Where do you see the influence of this disposition on your work?

To enter the desert is to relinquish shelter. To place yourself in the open, in a place of dramatically altered attention. It’s a stripping away of the self’s defenses. The sun is the voice of god. In all my so-called “creative” writing, I’ve tried to sustain a kind of radical sincerity, to keep myself vulnerable to the nuances of feeling, perception, consciousness. It’s a stance that doesn’t lead, as one might suppose, to simplicity or even clarity. The multiple voices in my poems aren’t a mask; they’re a nakedness. Of course, sincerity isn’t ever enough for art, but irony doesn’t touch the places that matter to me.

5. Many writers fall in love, live together, and work in the same space. Their passions intertwine and each inspires the other’s creativity. You and C.D. Wright were married, had a house in Rhode Island, and both taught at Brown University. One stanza reads: “There’s / a sub-level attunement between us. Our interactions / dilate, contract, and extend. And the feeling of all that / is the measure of how we’ve lived.” What are the benefits to this type of relationship? Are there any concerns?

Again, I have that sort of attunement now with the artist Ashwini Bhat. And I think it’s in our most intimate relationships that we discover the composite nature of the human soul, how we’re built from many separate identities. Our close proximity to others and our love for them initiates a slow bleed between bodies and minds. As I tried to emphasize in Twice Alive: an Ecology of Intimacies, when we open ourselves to the deep possibilities of intimacy, we fill in with the “more than ourselves.” Through our shared griefs and joys, our shared memories, our ordinary days (what is ordinary? What moment of life isn’t seeded with awe?), and in the responsibilities we take on, our identities can, to some extent, fuse.

It’s in our most intimate relationships that we discover the composite nature of the human soul, how we’re built from many separate identities. Our close proximity to others and our love for them initiates a slow bleed between bodies and minds.

6. I once received a writing prompt from C.D. that asked us to describe marriage without referring to anything personal. You write in the book: “Marriage, a divination of resonant relations.” How else would you describe marriage without referring to your own?

But when I wrote that, wasn’t I referring to your marriage? Isn’t it, too, a divination of resonant relations? I’m not writing about the social construct of marriage, but about what comes into play in a recursive, interactive mutuality. Not just the event of grazing together in the same pasture, but that “constancy/ to something beyond myself” that I return to again and again to in Mojave Ghost.

7. The passing of a loved one is processed very differently in certain cultures, religions, and countries. In Mojave Ghost, you write: “…when they tell me I need / to move forward… aren’t they themselves prompted / by an overbearing concern for control…” How has living in the U.S. impacted your grieving? How have different poetic traditions shaped your view of grief?

In her book Consuming Grief, Beth Conklin mentions that endocannibalism in Melanesia is mostly aimed at preserving, perpetuating, and redistributing elements of the deceased. Instead of trying to overcome grief, you can take it into yourself, accept it as a permanent part of who you will be henceforth. I’ve always been fascinated by the way that many of us have consumed, metaphorically, the dreams that our beloveds once told us, dreams that never existed in the world except inside the mind of the dreamer, that most intimate and usually inaccessible place. When the beloved is gone, those told dreams are among the most fragile and mysterious traces left behind. We carry them as talismans that reassure us of the presence of someone else within us.

8. You switch between first, second, and third person throughout the book. What was your intent behind this transition from personal to direct to general?

The latter half of Mojave Ghost was written during a period of two years when I was taking hikes along the 800-mile San Andreas Fault. I was finding that whenever I looked at one thing—a line of palm trees at the base of a hillock, a remembered conversation, my wife walking beside me, a red ant sinking beneath the sand in the ice-tong jaws of an invisible ant lion–I was encountering a collage of relationships. And like the land itself, fractured and dynamic under my feet, I began to experience myself as relational, without a fixed essence. I became more aware of my moving parts, my minds, my interruptions, my craquelure. This desert insight, which certainly isn’t original (look at the paintings of the Cubists or the Buddhist sutras) but which I felt more intensively than ever before, was that the self is also an unstable collage, a multiplicity, a vigorous interchange of perspectives. Only habit, boredom, or ego can convince us we are singular and closed-off, the central elements of an enduring, steady-state system. On those meditative hikes, what I called myself split into a congeries of selves. And that’s what accounts for the restlessly shifting pronouns.

9. There are a series of short stanzas towards the end of the book that each start on a new page. For me as the reader, the act of flipping through resembled the hike that is described. Why did you change length so distinctly in this section?

Precisely for the reason that you experienced. To render the words more quiet, smaller, to surround them with a desert of white space. And to slow down the pace of the reading. To build in longer moments of resonance.

I’ve always been fascinated by the way that many of us have consumed, metaphorically, the dreams that our beloveds once told us, dreams that never existed in the world except inside the mind of the dreamer, that most intimate and usually inaccessible place. When the beloved is gone, those told dreams are among the most fragile and mysterious traces left behind. We carry them as talismans that reassure us of the presence of someone else within us.

10. There are references to Arthur Rimbaud, Langston Hughes, and William Shakespeare. Who have been the greatest influences on your writing? If you could thank any writer for their contribution to literature, who would it be and why?

CD Wright. A deeply ethical writer, she grew up in the Ozarks of Arkansas as the daughter of a country judge and a court reporter. There she picked up a keen, signature, vernacular voice that came to characterize most of her writing even as her work became more insistently innovative and her diction, syntax, and formal strategies expanded, infused by her sophisticated intellectual bent and an exuberance for lexical particularity.

I mention CD’s ethical orientation from the start not as encomium, but because we see that orientation in ALL her books. One With Others and One Big Self, each composed— like Indra’s net—as linked sequences so interconnected that they can’t rightly be represented in excerpt, are most obviously focused on dignity, racial justice, and intersubjective responsibility. Not of course as philosophy or polemic, but as powerful, strikingly original poetry. Even when we look back to her earliest poems, “Obedience of the Corpse” or “Tours,” for example, we see struggle and innocence, ethical gestures of tenderness and care in a world of brutalities.

Forrest Gander was born in the Mojave Desert and lives in California. With degrees in geology and literature, he taught at Harvard University and Brown University. Gander is a translator and the author of many books of poetry, fiction, and non-fiction. Besides the Pulitzer Prize, he’s received the Best Translated Book Award and fellowships from the Library of Congress, the Guggenheim, Whiting, and United States Artists Foundations.